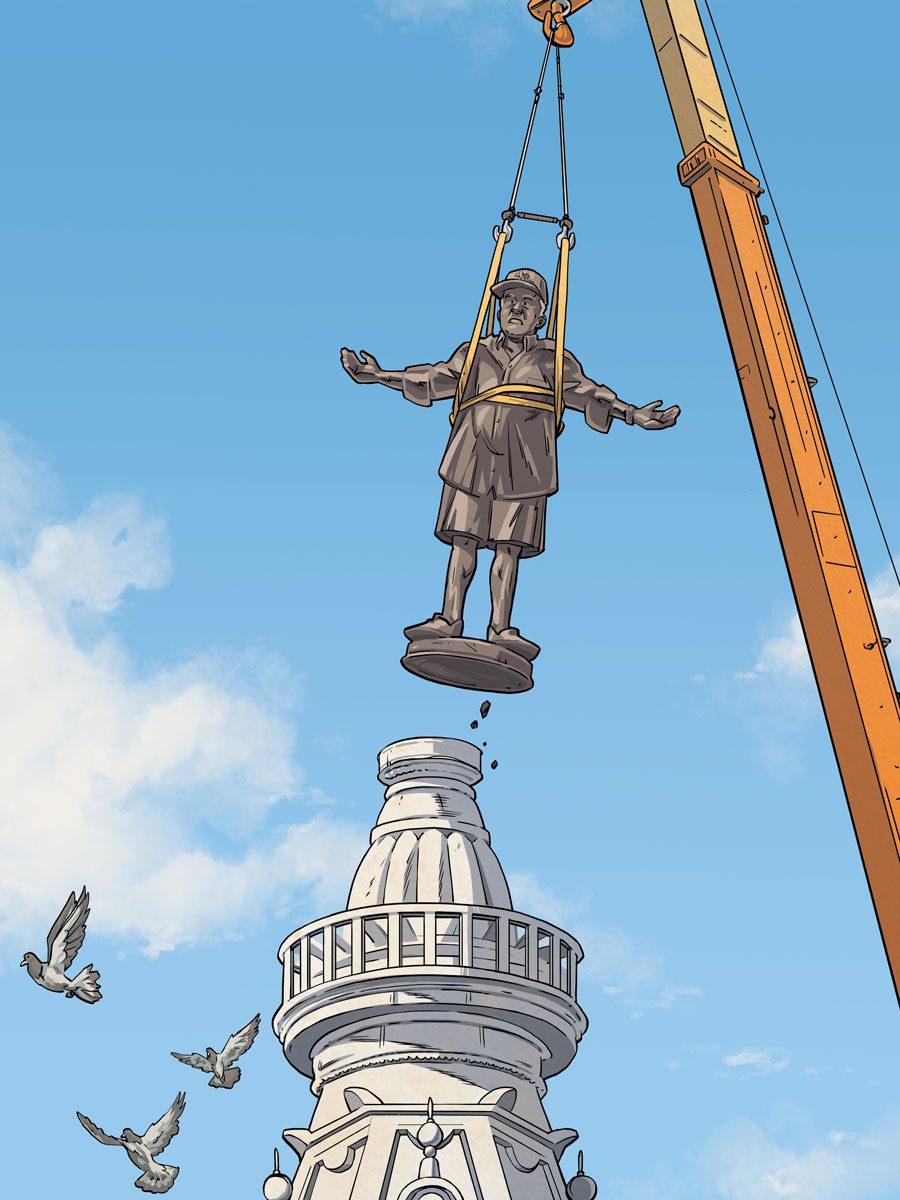

Life After Johnny Doc

How the conviction of Philly’s most infamous power broker is changing the city — for better and for worse.

John “Johnny Doc” Dougherty had become a Philadelphia political institution. Illustration by James Boyle

John Dougherty was out on a leisurely walk. Destination: the James A. Byrne federal courthouse. It was the first week in October, and Johnny Doc, head of the Local 98 electricians union and arguably the most powerful person in Philadelphia, was set to stand trial for corruption. The charges, unveiled two and a half years before in a 116-count indictment, were so abundant and varied that they had to be split into two trials: the first covering Doc’s relationship with then-City Councilmember Bobby Henon, who was on the Local 98 payroll for $70,000 a year in an arrangement the feds argued was an in-plain-sight bribe, and the second, scheduled for this September, covering embezzlement of union funds — $600,000 in all — allegedly spent on everything from laundry detergent to department-store gift cards to swimming-pool maintenance to home repairs.

Doc, wearing a boxy navy blue suit and wide pink tie, his short white hair casually flitting about in the wind, crossed the street near Independence Mall and ambled toward his destination. The possibility that he might be about to lose his own independence seemed far from his mind. With an entourage of 10 or so people trailing behind him, he had all the delirious confidence of a heavyweight champ entering the ring. He waved to the media scrum before him and flashed a wide smile, lips covering his teeth. He cracked jokes in his nasal South Philly accent (“Come on, that’s too close, that’s a bad picture!”), answered questions (Do you expect to take the stand? “I hope so!”), made quasi-Trumpian pronouncements (“Ze-ro crimes!”), and offered predictions (“I will walk away with this”). Then he entered the courthouse.

Seven weeks, 52 witnesses, and 126 wiretaps later, the verdict was in: guilty, Doc on eight counts, Henon on 10.

Even for Philadelphia, with its unbelievable propensity for churning out corrupt politicians — state senators Buddy Cianfrani and Vince Fumo (back-to-back representatives of the First District, a seat Doc himself once ran for); City Councilmember Rick Mariano (former Local 98 member whom Doc helped elect); district attorney Seth Williams (made a cameo in the Doc indictment); Congressman Chaka Fattah (no cameo); and the list could absolutely go on — this came as a surprise. It was surprising in large part because Doc had been on the radar of federal authorities for so long and yet had managed to remain unscathed. He had been under investigation in 2006, when longtime friend and electrical contractor Gus Dougherty (no relation) was accused of selling him a Shore condo on the cheap and performing more than $100,000 of renovations at Doc’s Pennsport home for free. Then, in 2016, that house was raided by the FBI, which produced memorable footage of Doc chatting with the media from his front doorstep, looking unperturbed in an untucked white button-down with the sleeves rolled up, khaki shorts, and a flat-brimmed Sixers cap. He acted untouchable, and for quite a while, he was.

At the trial, the government focused its case on a few choice anecdotes: Doc threatening the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia with Licenses and Inspections violations for using non-union labor to install MRI machines; Doc and Henon working behind the scenes during Comcast franchise agreement talks to strike a secret deal stipulating that the cable company use Local 98 labor; Doc getting Henon to draft tow-truck regulations after Doc’s vehicle was nearly towed; Doc ordering Henon to support soda-tax legislation; Doc and Henon conspiring to disrupt a revision to the plumbing code in order to secure Doc’s election as head of the Philadelphia Building & Construction Trades Council. Doc was portrayed as the boss and Henon the employee, albeit one who could occasionally be insubordinate. In one conversation caught on a wiretap, Doc complained about Henon to the Local 98 political director, saying, “The fucking thing we ask [him] to do, [he] doesn’t do. You have to hold him a little more accountable.”

Seen in another light, though, that snippet of conversation could be interpreted as something else: Doc trying to pressure an official he helped elect, also known as politics. “They’re just doing exactly what they were paid to do,” says the former business manager of Steamfitters Local 420, Anthony Gallagher. “We’re paid to try to get people elected and make decisions that help people build.” John Bland, business manager of Boilermakers Local 13, calls the charges a “personal attack on labor.” Even people who surely aren’t on Doc’s Christmas-card list, like Ken Weinstein — a developer who battled Local 98 a decade ago over using non-union labor for a Germantown project — had to admit that what was presented at trial didn’t look all that different from “tactics that I think other people also use.”

This is what made the Dougherty trial fascinating — or terrifying — for so many in the city’s political class. Unlike Fumo’s trial, which probed whether the state senator had abused his power by using staff for personal errands and whether he’d bilked a nonprofit, this one offered up a much more elemental question: What’s the line between legal influence-peddling and illegal corruption?

When the verdict came down on a November afternoon, the local media gathered giddily around the courthouse, waiting for Doc to emerge. A TV reporter speculated on which exit Doc would use — front or side? “John Dougherty typically doesn’t go out any side doors,” the reporter said with assured gravitas.

Not five seconds later, Doc emerged. Side door. He removed a surgical mask and approached the fortunate reporters who had correctly predicted his whereabouts. “We’re going to go back and regroup,” Doc told them. Even now, he seemed to act as if he’d just received a traffic ticket, not a conviction that could lead to 20 years in prison. (His sentencing is scheduled for late April, to say nothing of how his trial for embezzlement may go.) “I am very comfortable,” Doc said. “You don’t see me blinking, right?” He thanked the media for “the way you covered this,” then got into a white SUV. He flashed a thumbs-up as he was driven away.

John Dougherty entering the federal courthouse at the beginning of his trial in October. / Photograph by Matt Rourke / Associated Press

But he didn’t answer the biggest question — the one no one asked because until just a few minutes before, it hadn’t seemed possible. Johnny Doc — one of the state’s most powerful Democratic donors, anointer of the current mayor — is gone, right before a trifecta of consequential elections: a contested governor’s race that could end years of Democratic leadership in Harrisburg, a Senate race of massive national import, and a crowded 2023 mayoral race that will determine the course of the city for years to come. What happens next?

After Doc ran for Vince Fumo’s state Senate seat and lost to Fumo’s handpicked successor, Larry Farnese, an impromptu celebration broke out along Passyunk Avenue. Fumo, despite a pending 137-count indictment against him, was rapt, chanting, “Doc is dead!”

On a brisk day in December 14 years later, Fumo is sitting on an ornate royal blue sofa in the living room of his Spring Garden mansion, all but chanting “Doc is dead!” again. Completely backlit, with the afternoon sunlight pouring through giant windows behind him, he looks like an anonymized whistleblower in a documentary. But Fumo is speaking very much on the record about Doc, his erstwhile political friend turned longtime foe — or, as he calls him roughly 10 seconds into our conversation, a “jerk-off.”

While Fumo’s appraisal of Johnny Doc is a tad Fumo-centric — “He didn’t just want to be like me; he wanted to be me,” he says at one point — he does have a pretty unique perspective here. Who better to speak about the ins and outs of being a convicted political kingmaker than the city’s last convicted political kingmaker?

But first, the backstory. Johnny Doc assumed control of the electricians union in 1993. (Fumo says Doc ended up in power thanks to him — he put in a good word for Doc as a favor to his staffer Jim Kenney, who was Doc’s childhood friend.) He then made a simple, transformational decision: He convinced his members to dramatically increase — five times over, according to one report — their donations to the union’s political fund. (Doc didn’t comment for this story. His spokesperson, Frank Keel, said that his attorneys “shot down” the idea.)

It wasn’t quite a war chest yet, but it got Doc a seat at the table. He became close to then-mayor John Street and later secured a position as chairman of the Redevelopment Authority. Like Fumo before him, Doc didn’t limit himself to parochial Philly politics. He was, former governor Ed Rendell says, “smart enough to give to candidates and elected officials in other parts of the state so he could build a constituency in Harrisburg.” Indeed, it was Rendell who appointed Doc to the Delaware River Port Authority, yet another powerful development board (and one that Vince Fumo was once on, too, Vince Fumo would like to point out).

Doc’s strategy paid dividends. By 2008, he was powerful enough to be feuding with Fumo — and for it to be considered a fair fight. After Fumo’s indictment, Doc made his ill-fated foray into electoral politics, running to succeed the longtime senator and spending north of $1 million on the campaign. He lost. Cue the chants.

But Doc wasn’t dead — far from it. When Fumo was convicted of all 137 corruption counts the next year, it became clear that a new, unelected position would be opening up: last power-broker standing. “It was like Iran and Iraq,” Fumo says now from his couch. “When you took out Saddam Hussein” — Fumo is the dictator in this construction — “all of a sudden, Iran got strong.”

At the time of the corruption trial last year, Doc was as powerful as ever. Local 98’s political action committee had $13 million in the bank, and in return for that tithe, its members were performing roughly 75 percent of all electrical work in the city, according to some estimates, and had seen their (inflation-adjusted) hourly wages increase by nearly 30 percent since Doc’s inauguration as business manager 30 years ago. Doc had become head of the Building & Construction Trades Council, the influential umbrella organization of labor unions. He’d elected a childhood friend (Jim Kenney as mayor — $550,000 donated to an independent-expenditure PAC) and a family member (Kevin Dougherty as a state Supreme Court justice — $750,000 donated directly to the campaign). That support of his brother in 2015, along with two other Democrats, helped liberals take control of the court — the same one that would throw out the state’s gerrymandered Congressional maps and toss the Trump campaign’s lawsuits seeking to overturn the 2020 election. Then there was former Local 98 political director Bobby Henon on City Council.

Money and friendly elected officials were only part of the equation. Doc’s most singular skill might have been his personality. He was a prolific talker — “a verbal Rubik’s Cube, spinning all over the place,” as former mayor Mike Nutter puts it. He had connections, built over decades, at every level of government and throughout various bureaucracies. Everyone was just one very long-winded phone call away.

“He is a force,” admits State Representative Jared Solomon, one of the few Philadelphia elected officials to call on Henon to resign after his indictment. (Solomon says that resulted in “threats and intimidation” from the Doc camp, though he won’t elaborate.) “He is a showman who successfully developed almost a cult of personality for decades and accumulated power in every nook and cranny of the city and many places around the Commonwealth.” Rendell puts it a little more charitably, although the message is essentially the same: “He spent a lot of time getting to know elected officials, getting to know their families, getting to know what they care about outside of politics. And he got to know who he could push and who he couldn’t push.”

Before we can answer what Doc’s absence means, we need to consider what his presence has meant. As with everything in Doc-world, there are no clear-cut answers.

When it came to making sure his Local 98 electricians got hired for work, Doc could be unsparing. Once, when a single franchise of the burger chain Five Guys hired non-union contractors to fix some wiring in 2008, Local 98 picketers appeared. Doc also made a point of keeping tabs on up-and-coming developers, letting them know, in his totally-just-a-premonition way, that they’d be working together soon. One developer, who declined to speak on the record, says that Doc summoned him to one such meeting, then casually mentioned details about his family, like where his dad took vacations. “They knew a lot about us personally, which was part of their bag of tricks to try to intimidate you,” the developer says.

These could be construed as relatively minor incidents, at least compared to a 2002 Inquirer report on a series of National Labor Relations Board rulings that found Local 98 had violated labor laws more than a dozen times over a span of six years. In one case, a group of Local 98 guys surrounded a 19-year-old electrician from a different IBEW local and slashed his van’s tires with an ice pick. In another, a Local 98 organizer told employees who were about to take a union vote that he knew where their wives and children lived.

If some of this sounds far-fetched — which is the Local 98 line when there are allegations of untoward behavior — consider the story of Post Brothers developers Matt and Mike Pestronk. In 2012, the Pestronks were attempting to build a large apartment building in Callowhill, the Goldtex. They made two radical moves. First, they bid out their project to union and non-union contractors, which predictably escalated into a battle royale between them and the trades. Mike Pestronk alleged that he was followed for a year, that then-Councilmember Jim Kenney repeatedly and illegitimately called L&I on the project, and that once, a rack of ribs mysteriously ended up under the hood of his truck, causing animals to chew the wiring. The trades countered that the Pestronks were using undocumented labor and fostering work conditions so abysmal that workers had to urinate in bottles.

The Pestronks’ second radical move was simpler: They started recording their job site. It was all posted to YouTube — building trades members dumping oil in front of the construction site’s driveway in the middle of the night and pummeling one of the Pestronks’ non-union employees. In the end, the Pestronks built their building. Three years later, a higher-up in the Ironworkers union who’d once threatened to burn a Post Brothers crane to the ground if it was brought onto the job site pleaded guilty to arson and extortion charges in a sprawling case that had to do with threatening non-union developers.

Such stories aren’t limited to the developer set. One campaign veteran speaks of veiled threats, broken windows, and Doc allies showing up to people’s houses in the middle of the night during the 2008 Farnese race. Once, in a story that quickly made the rounds, Doc warned Farnese’s staff not to attack him with negative ads. “You never what knows happens if you go negative,” Doc purportedly said. “I’ve got a bunch of guys, and you never know what they’ll do.”

Talk to some other people, though, and a different Doc emerges. Ed Rendell gushes about how Doc convinced skeptical building trades leaders to embrace the Republican National Convention in 2000, when the city was still in the early years of its renaissance and needed all the support, even right-wing support, it could get. Similar tales abound: Doc helping to secure the pope’s visit in 2015; Doc advocating for the DNC in 2016; Doc calling up power players to land the NFL draft in 2017. Doc famously crossed the carpenters’ picket line at the Convention Center in 2014, putting an end to years of labor strife there (although before we hail Doc as a Convention Center savior, keep in mind that Local 98 also once shut off the power at the center during a labor dispute three days before a convention was set to begin). The Market Street East development that has transformed part of downtown? That was Doc; he helped find the developer and convinced the national building trades pension funds to invest in the project.

You can see why it’s become popular, then, to suggest that there are two eras of Doc. Old Doc: picket lines and threats. New Doc: driving big-time capital to the city (and, sure, some picket lines still, too). The New Doc credo is that what’s good for electricians is also good for Philly.

But when, exactly, did Old Doc end? Did it ever? Last March, Doc was charged with a count of extortion. His nephew, Gregory Fiocca, was working for an electrical contractor and allegedly not showing up for work. When confronted by his boss, Fiocca beat him up, telling him, “I’m going to punch you in your fucking face. … I’m calling my uncle already. We’re pulling everyone off the job.” The same day, the federal government alleges, Doc threatened to do just that, and said he’d make it impossible for the contractor to ever secure a large electrical job again. (This third trial is scheduled for May.)

So maybe there hasn’t been some great change in personality. Maybe there’s just one true Doc, hyper-focused on securing or defending benefits for his people — his union, his family, occasionally both at the same time — no matter how it gets done. When that means greasing political connections for a huge project that benefits the entire city, that’s great. When it means threatening a contractor or bribing a City Councilmember, that becomes a harder sell.

After doc’s conviction, the Philadelphia political class seemed stunned into silence. Jim Kenney told reporters, “I have my own opinion, which I won’t express,” thereby expressing his opinion. (He declined to comment for this story.) Councilmember Helen Gym, a Henon ally who’s also received Local 98 support, didn’t comment. City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart, never one to resist doling out a barb, offered a mostly anodyne remark about how “it’s time that the people of Philadelphia have a city that works for them.” Even Councilmember Maria Quiñones-Sánchez, who’s been calling on Bobby Henon to resign since 2019 (he finally did in January) and is no friend of Doc’s, decided not to chime in.

Doc, however, isn’t without his defenders. They’ll point out that it wasn’t illegal for City Councilmembers like Henon to have outside employment, and that others have conflicts of interest, too. Allan Domb has considerable real estate interests, including a minority stake in the Rittenhouse restaurant Parc, but that didn’t stop him from introducing the bill that made streeteries permanent. Derek Green and Brian O’Neill have side gigs with law firms. “This isn’t about members of Council having other jobs — if it were, people like Domb or Green would be complicit too,” union organizer Mindy Isser wrote in a November Inquirer op-ed before Doc’s conviction. “Instead, it’s another campaign to demonize organized labor, union members, and their political allies.” What’s more, the defenders say, Henon disclosed his job with Local 98 on multiple city ethics forms. They tend not to note that Henon’s disclosures — in which he described his job simply as “electrician” — arguably raised more questions than answers. Surely he wasn’t going around repairing electrical connections on the side? Domb, on the other hand, submitted a 25-page disclosure for 2020, listing 535 different sources of income, down to the individual buildings and apartment units he owns.

Caliber of disclosures aside, the argument about Henon’s side job ultimately boils down to this: Was it a bribe? His lawyers said of course not and made a point that seems compelling on its face: Henon couldn’t possibly have corrupted himself, because every action he took — even if Doc recommended it — he would have taken in his own right. In this telling, Henon following Doc’s commands isn’t so much a sign of obedience as a sign of agreement.

The government’s counter was less about the substance of the lobbying and more about the nature of the arrangement. Prosecutors alleged that Henon had no job responsibilities for the $70,000 a year he earned from Local 98 and pointed out that while the union’s federal disclosures listed him as an “office” employee whose work was 50 percent “general overhead” and 50 percent “administration,” when the FBI raided Local 98’s offices in 2015, it found no indication Henon worked in the building. If Henon had been doing $70,000 worth of legitimate work in addition to his Council job and Doc made many of the same asks, presumably that would have been normal (at least by Philly standards) lobbying. But this was the fundamental issue: The moment Henon took money from Doc knowing it was meant to influence his Council votes, he stopped representing his constituents. It didn’t even matter, the government emphasized, whether Henon ever was influenced by Doc. The arrangement itself was illegal. That’s the difference between Henon and Domb. You can argue that Domb had a conflict with his streeteries bill and shouldn’t have been the one to propose it. But you can’t honestly say Domb was co-opting the powers of his office for his company’s benefit; the bill covered huge tracts of the city. And the apartments that produce his outside income exist. Henon’s ostensible job for Local 98 didn’t.

John Dougherty after the FBI raided his home in 2016. / Photograph by Charles Fox / The Philadelphia Inquirer / Associated Press

One of the other arguments you’ll hear trotted out in favor of Doc basically amounts to Well, everyone else was doing the same thing. Not exactly a bulletproof defense for the courtroom, but the funny thing is, it has some merit. “I talk to people who work in other cities across the country, and they’re like, ‘Philadelphia is out of the fucking 1980s,’” says a former City Hall insider. When Kenney needed support for the soda tax, he lobbied then-NAACP head Rodney Muhammad; later, Muhammad ended up with a job through the campaign. “That to me is as clear a line of quid pro quo as the Bobby and Doc stuff is,” says the insider, “but that’s a relatively commonplace type of transaction.” Nutter says that occasionally when he was on Council, he would be talking with someone who was lobbying him on this or that issue, only for the person to casually pivot to, “Oh, by the way, when’s your next fund-raiser?”

There’s hope among some officials that Doc’s conviction will finally lead to reforms that could kill off this endemic behavior. The general lack of outrage from the politicians who would be the ones to pass these laws, however, doesn’t exactly make for a preliminary vote of confidence.

At least one change is already here: Ryan Boyer is now the head of the building trades. Boyer, who’s also the business manager for Laborers District Council, the city’s only predominantly Black building trade union, is distinct from Doc in many ways. He’s not as brash. He doesn’t appear to have many enemies. No one — not even the developers who can’t wait to anonymously savage Doc — has a bad word to say about him. Boyer sees himself as the Colin Powell to Doc’s Donald Rumsfeld. “I know when to go to war,” he says. “But when you break it, you bought it. I’m real careful about when to go to war. I’m not afraid to go to war, but I’m reticent.”

When it comes to substance, though, the Doc-to-Boyer transition figures to be less stark. The main goal — getting more jobs for construction workers — won’t change. Even the most optimistic developer knows that the building trades’ power as virtually the only source of labor for large construction projects is unlikely to evaporate. So no, Boyer doesn’t think the trades are any weaker than before Doc’s conviction. In fact, he says, “Sometimes, adversity can unite you.”

That’s one possibility. Another is that adversity splinters you. Doc was skilled at forging consensus among the labor-leader egos inside the Building Trades Council. “We don’t get to say ‘Jump’ and people say ‘How high?’” says Pennsylvania AFL-CIO president Rick Bloomingdale. “We get to say jump and they say ‘Why?’” Boyer will have his work cut out for him. As for Local 98, the union figures to lose some influence without Doc. But it would be unwise to bet against a union that still has $13 million in political money, not to mention plenty of bodies to tap for get-out-the-vote endeavors.

Then there’s the question of the coming races for senator, governor and mayor. With so much national money flooding the statewide races — not to mention multiple millionaires running — Local 98’s cash figures to have less impact. Doc’s absence should be felt more locally, where political pundits now talk of a “power vacuum.” Mustafa Rashed, a longtime political consultant, suggests the service-sector unions, with their “large member organizations that have been very vocal, especially since the start of the pandemic,” could benefit. “Somebody has to emerge that has the ability to get everybody together,” adds campaign consultant Neil Oxman, who produced Doc’s TV ads in support of Kenney in 2015. Rendell likewise says, “John’s ability to get things done will be missed in the short run.” Even Bloomingdale acknowledges there’s no immediate heir apparent to Doc: “People are still developing.”

Boyer, undoubtedly one of those people, rejects the notion of a power vacuum, calling it “wishful thinking.” It certainly is possible to imagine a business-as-usual scenario where the trades unite behind Boyer and support someone like Helen Gym for mayor. But it’s just as easy to imagine Gym wounded by an anti-Doc backlash, especially since she, too, was caught on a wiretap presented at the trial — collateral damage — discussing whether she needed to report Local 98 Eagles tickets on her campaign-finance disclosures. (She did need to but didn’t until two years later, per her spokesperson.) In that climate, a longtime Henon critic like Quiñones-Sánchez could take up the Nutter-esque mantle of good-government City Councilmember. Or maybe voters will become so sick of politicians that they choose not to elect one at all. Jeff Brown, anybody?

But hold up — could it be premature to even be writing the phrase “Doc’s absence”? Doc has filed a motion for a new trial or an acquittal, and while it’s a Hail Mary (and he’s still got those extortion and embezzlement trials to come), overturned cases on appeal aren’t unheard-of. It could take a year or two for the case to wind its way up the courts, according to Penn legal expert David Rudovsky: “It won’t be finally resolved for some time.”

John Dougherty as he emerged from court at the end of his corruption trial in November. / Photograph by Matt Slocum / Associated Press

Meanwhile, one developer believes the election of Mark Lynch as the new business manager of Local 98 is evidence the old leader is still at the wheel, handpicking a “puppet” he can influence. “He might as well have been an anonymous cast member in the audience of a late-night show,” the developer says of Lynch. “He’s a nothingburger, no presence, can’t hold his own in the room with other unions.” A separate civil case filed by the Justice Department against Local 98 last year for election interference at least lends some credence to this theory. When a union member told Lynch he was planning on running for a leadership role in 2020, Lynch allegedly handed the phone to Doc, who berated the would-be candidate and insisted he not run. (Lynch declined to comment for this story. Frank Keel emphasizes that Lynch was unanimously elected by the Local 98 executive board. What that means at a union currently facing a lawsuit over election intimidation, well, your mileage may vary.)

There are other anecdotes in this vein. The same developer who calls Lynch a puppet claims he recently had a meeting scheduled with Boyer and other building trades leaders and that Doc tried to sabotage it, calling everyone except Boyer and imploring them not to show up. “More B.S.,” says Keel. Boyer completely denies this story, too, saying, “I can’t talk about fairy tales; I like to talk about reality.” The reality, he says, is that he and Doc are still in contact and on great terms: “John is always going to be a confidant of mine.”

Forget the backroom intrigue for a minute, though. Something is surely lost without Doc. If you read old stories about him from over the years, you notice they had an uncanny way of predicting the future. Doc mentions wanting to bring the DNC to Philly? Done. Doc mentions wanting to develop Market East? Done. Before the conviction, Doc’s union allies say, he was working on his dream project, years in the making, of extending the Broad Street Line to the Navy Yard. Boyer talks about grand plans for reimagining office space to attract high-paid employees, plus Doc’s efforts to land Philadelphia as a site for the 2026 World Cup. The question is: How indispensable was Doc — to Local 98, to the city’s big projects, to all of it? “If we have a gaping hole in the growth of the city and in the advancement of the city five years from now,” says Ed Mooney, vice president of the region’s Communications Workers of America union, “then we’ll have our answer.”

A former Local 98 staffer who worked closely with Doc says it’s worth thinking about his role in the political sphere in the same way. “It’s really hard to govern in a place like Philadelphia,” the staffer says. “We have fractious politics, there’s not clear consensus, there’s a huge leadership void. It’s really hard to get anything done. So there’s gotta be some deal-making done behind the scenes.

“I always tell people,” Johnny Doc’s former employee continues, “that if John didn’t exist, you’d almost have to invent him.”

Published as “Doc is Dead! (For Real This Time … We Think) ” in the March 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine.