Witchcraft, Boiled Bones, and All the Other Creepy Things We Learned About PA History in This New Book

Just in time for Halloween, Dark History of Penn’s Woods is the perfect book to keep you up all night.

The Dark History of Penn’s Woods is coming out on October 20th. Cover image courtesy of Casemate Publishers

Just in time for Halloween, Haverford’s Brookline Books has published Dark History of Penn’s Woods, a new book with the catchy subtitle Murder, Madness, and Misadventure in Southeastern Pennsylvania. (Hey, that’s us!) Written by Jennifer L. Green, a history grad at West Chester University before she embarked on a career as a guide at various local historical sites and museums, Dark History is a compendium of bizarre and spooky events hereabouts from the days of the earliest Swedish settlers up through a mysterious case of spontaneous human combustion (there’s a catchy acronym, SHC) in Upper Darby in 1964.

Along the way, Green offers some fascinating cultural analysis, quick summaries of everyday frontier life (the role of indentured servants; common funerary customs), and such phenomena as the widespread belief that touching an executed criminal’s body soon after his or her death could cure disease. (Ick!) It’s ghostly, it’s ghastly, and we guarantee some of the included photos (that Upper Darby case of SHC!) will stay with you long after Halloween has come and gone. Here, some quick highlights, sans spoilers, of course.

A Hotbed of Horror

Yeah, this state was settled by Quakers. But it turns out early Pennsylvanians were pretty darn wild, despite the sect’s bans on frivolity like dancing and gambling. Our early days saw far more homicide cases between the colony’s founding and the year 1801 than any other colony except for Virginia, where a lot more people lived. According to Green, the 1780s were particularly bloody, with 136 suspected murders in just 10 years — “more,” Green writes, “than the colony of Massachusetts tried in the previous 50.” Did you know that back in the day, you could be tried posthumously for committing suicide?

Chapter one starts out with a bang: “For fans of everything spooky,” Green begins, “Pennsylvania has a reputation as an unmitigated disappointment.” She cites Massachusetts’s witch trials, North Carolina’s “ghostly shipwrecks,” and Virginia’s celebrated entire “Lost Colony” of Roanoke as examples of more widely known mysterious goings-on. But, she explains, early Pennsylvanians were already renegades against England’s state religion, a fact that may have made them more sympathetic toward the kinds of outsiders other settlements were quick to label devils or witches.

In fact, William Penn himself once delivered the closing statement in a witch trial that found the accused, one Margaret Mattson, “guilty of having the common fame of a witch, but not guilty in the manner and form as she stands indicted.” In essence, she was found guilty of prompting her neighbors to think she was a witch.

All Bottled Up

Just because Quakers weren’t inclined to believe in witchcraft doesn’t mean it wasn’t practiced. A small dark-colored glass bottle unearthed at Governor Printz Sate Park in Essington, Chester County, in 1976 has been determined to date from the mid-18th century and is the first known example of a “witch bottle” found in America. English witch bottles containing bits of human hair, urine, blood, fingernails and the like were a form of “white magic” and were buried to spare households from supernatural disturbances.

The Essington witch bottle. Photograph by Marshall J. Becker

Pennsylvania’s early criminal code, writes Green, only featured two crimes punishable by execution, compared to the more than 200 such crimes back in Merrie Olde England at the time. This imbalance created a paucity of dead victims whose bodies could be used for what was then known as “stroking,” or “the gallows touch” — using the energy that remained in an executed body to cure the ill. Luckily, the rope used in a hanging could also be so employed and had no expiration date.

Suffer the Children

It was legal in England for constables to round up orphans and impoverished children from the streets and sell them into servitude in the Colonies. The famous Virginia Company would even place orders for shipments of such children to work in the fields. The little ones didn’t often live to suffer long. Green says records show that of 300 children shipped to Pennsylvania from England between 1619 and 1622, only 12 survived until 1624.

One such young person, William Batten, sent to work on a family farm in Concord Township, was soon offloaded to a neighbor farm where he promptly began hearing the voice of the Devil and … well, let’s just say it didn’t end well.

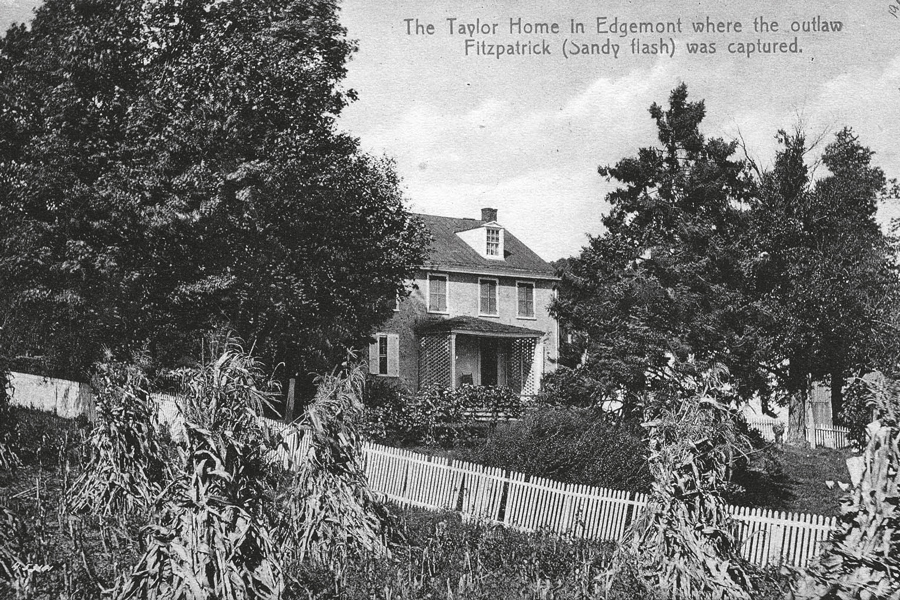

A popular postcard of the Taylor/McAfee home where James Fitzpatrick was allegedly captured. The home has since been demolished. Image via Keith Lockhart

Speaking of Chester County, it provided a homegrown rogue during the Revolution, in which plenty of local Loyalists and Quakers refused to fight. Highwayman James Fitzpatrick, a handsome young blacksmith, made quite a name for himself. A volunteer with the state militia, he was flogged for a minor rules infraction, turned coat, was repeatedly imprisoned and managed to escape, and had the good sense to target tax collectors in a crime spree (everybody hated tax collectors even then) that eventually … also did not end well for anyone involved, including the neighbors who earned a 1,000-pound reward — about $120,000 today — for turning him in. Too bad Fitzpatrick’s buds then burned your farm down, guys!

Remains of the Day

Ahem. Along the lines of historical facts you never particularly wanted to know, during the Crusades, Europeans who were reluctant to leave the bodies of deceased fellow soldiers interred in enemy territory (Charlemagne had outlawed cremation at the time) began to boil those bodies down to the bones so they could be transported home for burial more conveniently. (I mean. Who wouldn’t rather travel with a skeleton than a rotting corpse?)

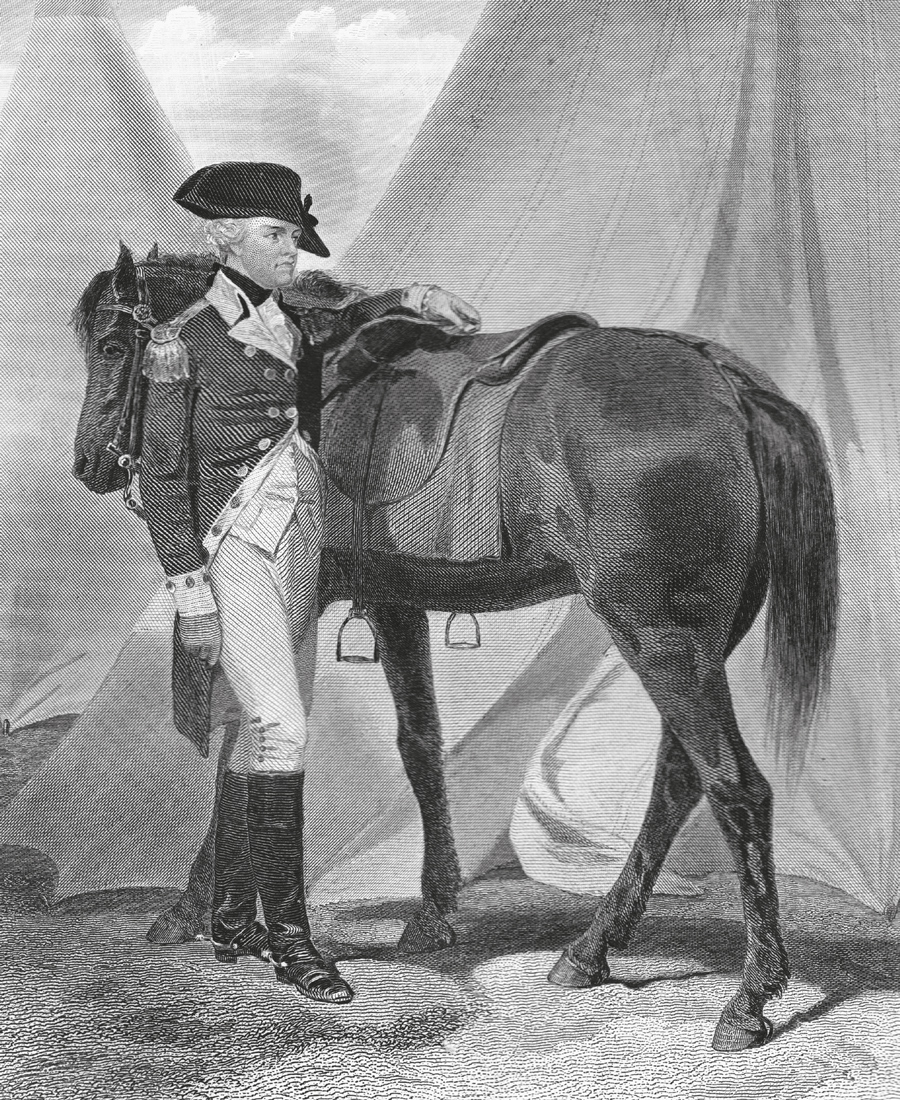

Anthony Wayne as a young man. Image via National Portrait Gallery of Eminent Americans from original full-length portraits by Alonzo Chappel Vol I, New York: Johnson, Fry & Co. 1862. Wikimedia

This was the same method used many centuries later, in 1808, by the son of the deceased Revolutionary War hero General “Mad Anthony” Wayne when he drove a small (very small) wagon to Fort Presque Isle, between Pittsburgh and Detroit, to retrieve the body of dear old Dad so he could be properly buried in the family burial plot in Radnor. When Wayne’s coffin was exhumed at the fort, it was found, to general shock — seeing as the man had been dead 13 years — to be barely decomposed, making it thus too big to fit in Sonny’s wagon. A physician on the spot suggested boiling the body for convenience’s sake. The pot in which the general’s remains were defleshed (the official term, in case you’re wondering, is excarnation) found its final resting spot at the Erie County Historical Society.

You’ll find loads of other cheery Halloween food for thought (did I mention that photo of SHC?) in this tribute to Philly-area weirdness, evildoing and death. Enjoy!