The Penn Museum’s New Galleries Reckon With Colonialism. Plus: Air Conditioning.

While most museums of archaeology shy away from the thorny issue of how they acquired their items, the newly renovated Penn Museum makes it part of the narrative.

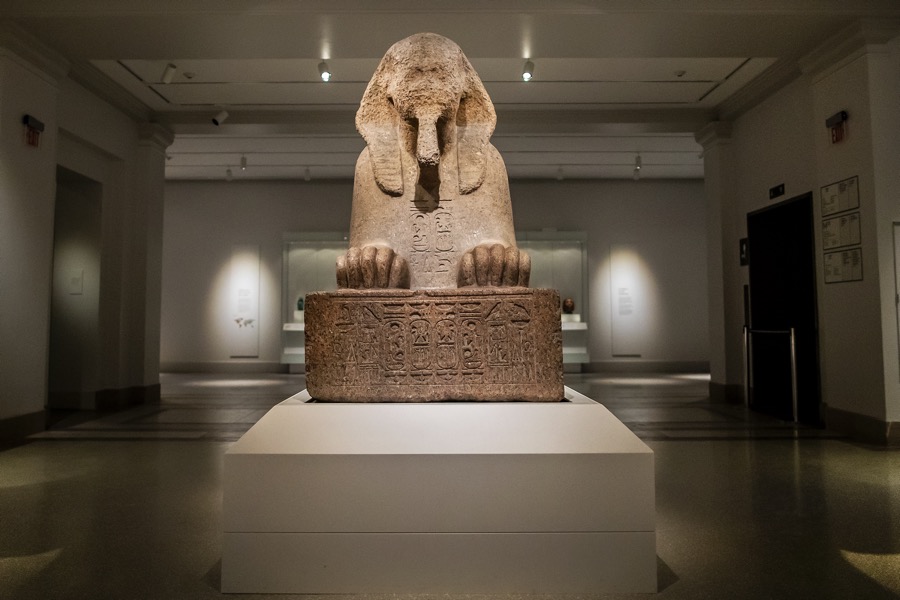

The sphinx of Ramesses II greets visitors at the new entryway in the Penn Museum. Photo by Eric Sucar.

Ancient Egyptian sphinxes are supposed to be the center of attention. So you can understand why the Penn Museum, as part of its ongoing $80 million renovation, moved its 25,000-pound Ramesses II sphinx from its former home deep inside the museum’s Egypt galleries to a new pedestal: front and center in the main entrance.

That is the most obvious of the changes to the museum. But — and no disrespect to the great pharaoh Ramesses II here — the new sphinx placement is also possibly the least interesting update to the 10,000 square feet of gallery space the museum reopened over the weekend.

Animating the years-long renovations has been a goal to make the museum — much of which hasn’t had an upgrade since the 1950s — more of destination for the public. Previously, the Penn Museum had mostly been a space for academics, which might explain how it could get by just fine all these years without air conditioning, and with bathrooms so old they could practically be displayed alongside the objects in the collection. “The museum world has gone on since the ’50s,” says museum director Julian Siggers, “and the expectations of the visitor have gone on, too.” (The Egypt galleries are next in line for renovations.)

But aside from the much-needed boost to museum amenities, the award for the most innovative renovation would have to go to the Central America and Africa galleries, which have received their first significant update in six decades. (Museum staff liked to joke that those galleries needed a refresh soon, lest they become historically designated.)

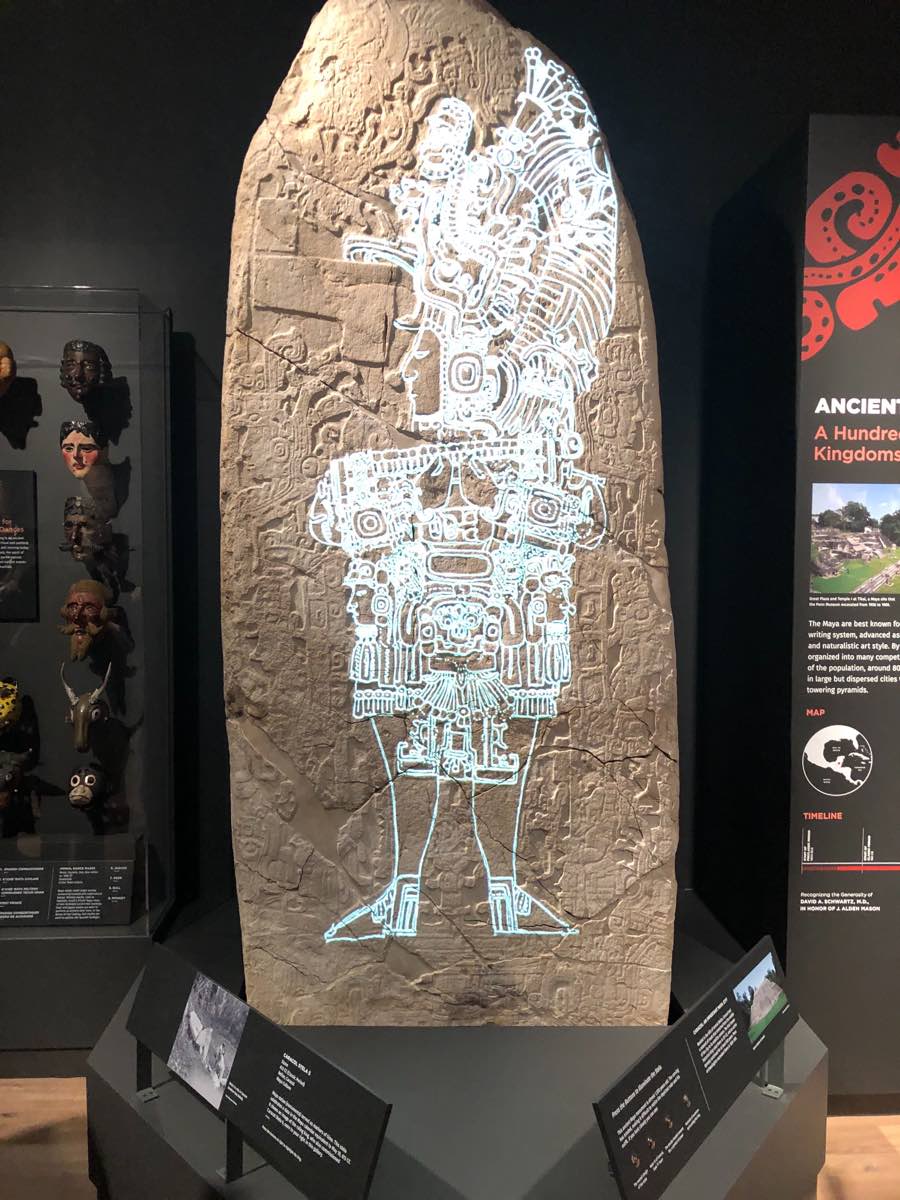

The new Mexico and Central America galleries finally look modern. Photo by Eddy Marenco.

In the Central America gallery, museum curators have figured out a way to use technology that actually enhances the experience, instead of just appealing to attention-span-starved children. On a recent tour, I counted at least 11 touch-screen tablets; one of them, situated next to a suite of objects from a site in Mexico, shows drone footage from the actual archaeological site, providing some nice context. In another bit of technological cleverness, a light projector shines on a stone carving, helping to decipher what the figures actually look like.

Photo by David Murrell.

The Africa galleries, meanwhile, have been completely reimagined in a way that places the legacy of European colonialism and looting directly to the fore. Instead of displaying objects and essentially ignoring their provenance — as most other museums tend to do — Penn has made that history part of the story.

Take, for instance, a small ivory armlet from the kingdom of Benin (located in present-day Nigeria). Rather than displaying the object on its own as it might have in the past, the museum created an interactive exhibit that walks you through the entire story — from when the armlet was first looted from the Benin royal palace by British soldiers in 1897, to when it was sent to the looter’s archaeologist brother in London, then donated to the Penn Museum only after the brother realized the armlet was worth little on the resale market. “We’re showing how to do an exhibit that decolonizes the museum space,” says Africa galleries curator Tukufu Zuberi.

But more than simply highlighting the colonial realities of provenance most other archaeological museums sweep to the side, Zuberi has also tried to make antiquity relevant in the present. “The idea was to get fresh with antiquity,” he says. And to do that, he commissioned a series of contemporary artists to create works in dialogue with the historic objects on display.

In the background, a contemporary artwork about the history of museums and looting. Photo by Eric Sucar.

The effect is to revitalize entire segments of the museum that have long been ignored by the public in favor of more popular objects — like that big granite sphinx now in the entryway. The Penn Museum has always had world-class objects in its possession. Now it has something more valuable: a modern curatorial vision.

Photo by Eric Sucar.

Photo by Eric Sucar.

Photo by Eric Sucar.

Photo by Eric Sucar.