How Do We Teach History in America Today?

Six Philadelphia educators discuss American history, equity and inclusion, critical race theory, and other hot-button issues schools and teachers face in 2022.

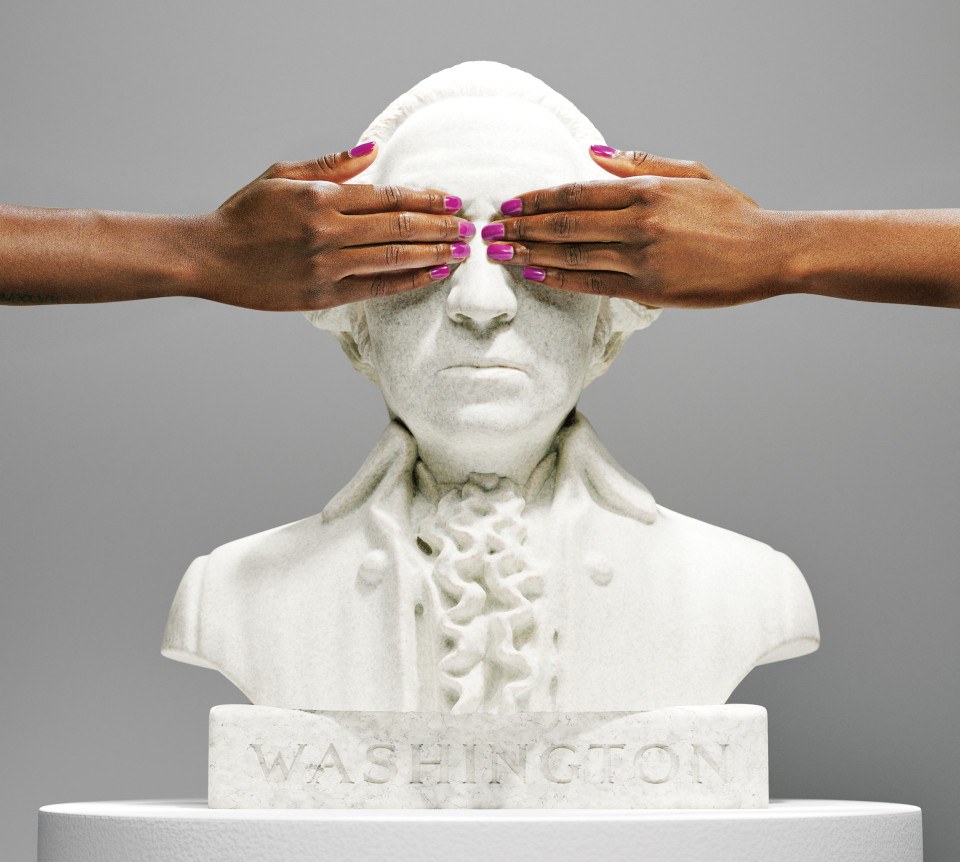

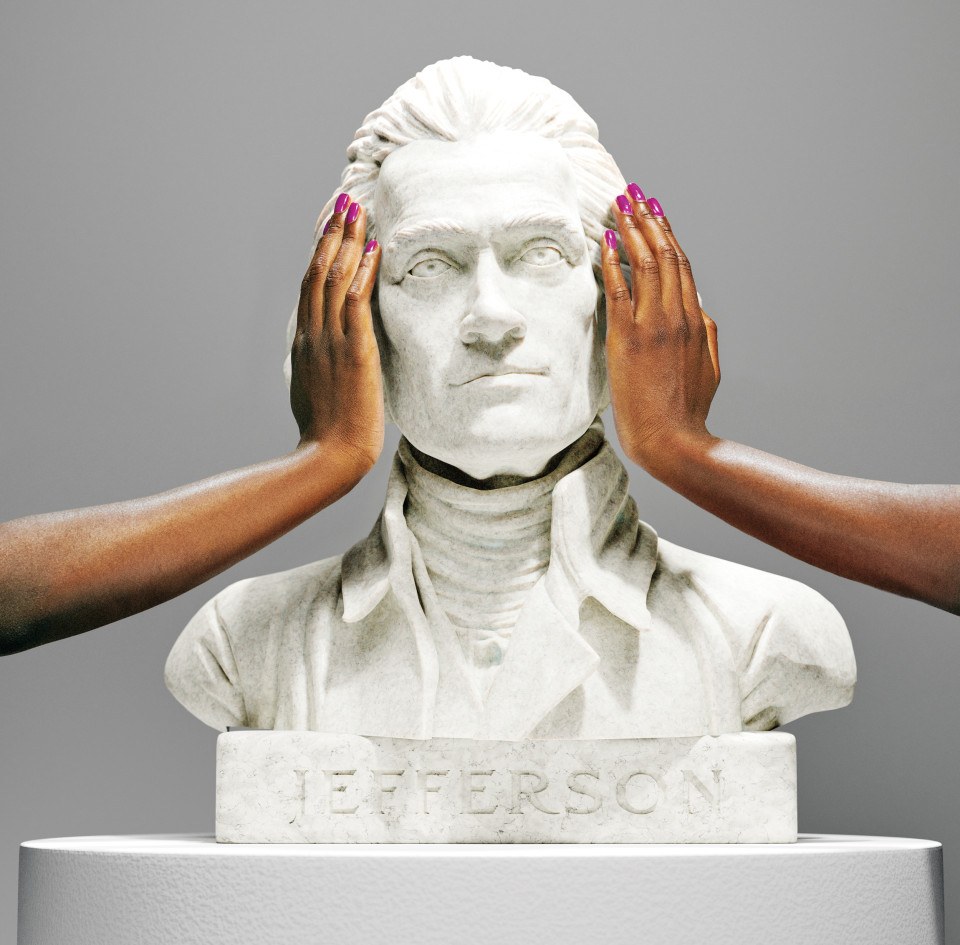

See no evil. Hear no evil. Teach no evil? / Photo-illustrations by Andre Rucker

On a Tuesday in late June, we gathered six distinguished local educators (meet the panel) in our offices in the Curtis building, just off Independence Mall, to ask them a question: How do we teach American history in 2022? Our query was inspired by the battles being waged in school districts across the nation — including many in this area — over equity and inclusion, critical race theory, book banning (and burning), transgender identity, and other hot-button issues of our day. Linn Washington Jr., a longtime journalist and a professor of journalism at Temple University, agreed to moderate the discussion. By coincidence, it took place just days after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. The conversation, which went on for more than two hours, has been edited for length and clarity.

Brian Howard: I want to thank everyone for being here for the Philly Mag panel discussion on education, because it’s an important topic — and it just got a lot more important. I’d like to thank Linn Washington for moderating this discussion. Considering we’re a city that trades so hard on its history, I think talking about how the heck we teach that history is incredibly vital right now. So I’m going to hand it over to you, Linn.

Linn Washington: We have a lot of great perspectives around the table, and I hope everybody feels free to speak freely. I don’t think any of us will be ruffled by anything anybody says, so don’t feel bad about stepping out.

Why don’t we start with the elephant in the room? There’s now a big pushback on the teaching of American history, and it seems to go in cycles. We make a little progress and fall back, and we make a little progress and fall back. Right across the street here, in front of the Liberty Bell, there’s a depiction of where George Washington lived when he was president of the United States, back when Philly was the capital. A part of that story that has always been suppressed is that Washington kept slaves. And he would cycle the slaves through every five months or so, because Pennsylvania had a law that said if an enslaved person was in the state for more than six months, they became free. The National Park Service knew about this for decades but didn’t want to say anything about it, because they didn’t want to make anybody uncomfortable. And when, about 20 years ago, they redid everything and changed the exhibit in the Liberty Bell pavilion, there was a fight about telling that story. Here we are, again, pushing back on it. So what is problematic with teaching real history in America?

James V. Fenelon: In sociology, you cut your teeth on critical race theory. Critical race theory emerged as a way to say: What are the laws and policies and maybe, in some cases, the practices that led us to the situation we’re in? That’s all that it was. That’s how it all started.

But that merges into a discussion of the Constitution or the Declaration of Independence. There’s a reason why Native people are called “merciless Indian savages” in the Declaration of Independence, and that’s to justify a genocidal attack against them. So how do you connect that to law and then to history?

Native people were basically an early version of enemy combatants; they were not citizens. I just did an analysis of the census, and the only people named in the census by race back then were white people. There’s only a gender difference noted for white people; there’s only an age level for white men. Why is that? Because those are the citizens: white men 16 years and older. Everybody else is not a citizen — not even white women, although later on, they’ll be included. Native people are actually the last people to be included, and even then, it was a second-class citizenship shared with other folks, especially African Americans.

Washington: The perspective and the history of the Native peoples were — not were, but still are — pushed to the back. But it seems there’s an element that always gets left out in our history, and that’s the history of the Latino people who were in the Americas prior to the arrival of the British colonists. Wilfredo, why do you think so much Latino history is pushed to the side?

Wilfredo Rojas: I think the media has a great deal to do with it by their blatant omission of coverage of stories in the African American and POC communities. And if you look back, capitalism plays a big role. The Spaniards and Portuguese and others went into Africa to rip away the slaves to bring to America after they committed genocide against the Native, Indigenous people living throughout Central and South America and the Caribbean. They needed to reinforce the labor pool because the Indigenous populations were diminishing.

Remember, the Spaniards had horses, and they had swords. The Indigenous people could not compete with horses and swords, so they ran up into the mountains to get away. If you look at the DNA of Latinos and African Americans, it’s usually the paternal DNA that’s European. Do you know why? Because of the rapes.

Washington: Abby, why do you think there’s such a resistance to a fuller construction and understanding of real history in America?

Abby Reisman: First, I think that people — and by that, I mean adults, or “grown-ups,” as my five-year-old would say — think kids can’t tolerate complexity. You mentioned that Washington was a slave owner. That threw grown-ups into crisis — “But he’s a hero!” “But he was a slave owner!” It’s like we can’t possibly hold those two thoughts together. But actually, kids can hold these two thoughts together. You know: “Bedtime is eight o’clock, but it’s New Year’s Eve, so you can stay up late” — they get it. “My teacher’s mean, but she also cares about me.” So I think there’s a fundamental mistrust of what kids can tolerate and their capacity for complex thinking. It’s not the kids who are necessarily uncomfortable or afraid; it’s the adults, and they project that onto the kids.

The second thing is that there’s a real conflation of what history is and what collective memory is. There’s the past. The past is like, “It happened, and we can’t retrieve it.” Right? Even if we went back in a time machine, you couldn’t retrieve the entire past. Then there’s history, which is how we tell stories of the past based on the evidence, or whatever we can retrieve. And then there’s collective memory, which is the myths and legends and stories we tell of however we define the collective. The collective can be my family, the collective can be society, the collective can be a particular culture or a subculture, etc. But it’s how we remember our past.

Our nation has a collective memory, as substantiated in monuments and memorials and textbooks. For many people, there’s a disjuncture between the stories our families have told, the stories that we see in our neighborhoods, etc., and the national narrative. And whenever there’s a disjuncture, when I hear something about my family that I didn’t know, that’s a disruption. That’s a realignment of my identity. I think that’s what happens for many white people who learn something about their collective past that runs counter to the stories they heard growing up. And there’s two ways through that: You either accept it and work it out and do the work to realign the story of who you are, or you reject it — violently — through censorship, through legal options. And I think what we’re seeing is, there are a few good men who can’t handle the truth.

Tabitha Dell’Angelo: Can I build on that just a little bit? I’m a teacher educator, but I’m also on a school board. And throughout history, there are these multiple concurrent realities that give us examples that could really teach kids how to grapple with moral dilemmas — these situations that come up for which there’s no clear answer. This is what everybody says we want for kids: We want them to be critical thinkers, and we want them to really be able to think about their world and their role in it and how they’re going to solve problems in the future. But when it comes time to actually do it, there’s this fear. And I think you’re right — it is coming from the adults.

Right now, even the best-intentioned history teachers are fearful, because the structure is such that if they say a certain thing, they fear they will lose their jobs. Even tenured teachers have said to me, “Oh, my employment is protected. But this position isn’t — they can move me, they can move my grade, they can move my subject, they can move my school, they can make me have to travel 45 minutes.” So they’re not really protected.

And to your point about collective memory, I thought of how we remember stories for which we have an aspect of connection, right? So I could see how the stories are something we would really hold on to as truth, as something we believe, as something we want to believe. The way we teach history is so dry and memorized, and we’ve pulled out all of the conflict, all of the realness about who Washington was, or who Woodrow Wilson was, and instead done that low-end purification where people have to either be heroes or villains and that’s it.

Ismael Jimenez: I wanted to piggy-back off that, too, thinking about the narratives that fit into a certain story line and the mythology that this society tells itself about itself based on the white supremacist killing of — genocide of — Natives and the enslavement of Africans. The idea of freedom for folks like George Washington was based on this idea of, “Well, I want the freedom to be outside of the king’s control, to take land, and then to enslave people and make profits.” But that doesn’t fit into the story line of what America tells itself, right?

It’s like cognitive dissonance; people cannot accept the fact that this racialized structure provides the framework and grounding and foundation to allow people to benefit from a fundamentally racist, white supremacist system. Nobody wants to hear that; it makes people feel uncomfortable. We’re like, “What are you talking about? My family didn’t own slaves; my family didn’t steal land; we worked hard! We came over here with nothing.” And that feeds right into the story line of the rugged individual, when in reality, all that was premised off stealing the land and then benefiting from economies and structures developed from the forced labor of Africans.

When I was a teacher, I always asked my students: “Harriet Tubman and George Washington supposedly worshipped the same God, right? But how can the enslaver and the enslaved worship the same God? What is the measurement of what they’re asking God for?” Then you start to question that: “Wait a minute; are you telling me that everything I thought to be true about this reality being fair — that everybody has an equal chance, and that we’ve made progress — ultimately is just a story line to rationalize the continuation, the perpetuation, of racialized exploitation?” I mean, people can’t handle that.

Rojas: Let me also add this. Remember where most European immigrants came from: highly industrialized countries. So they came with a skill set that was more industrial, and they could adjust to the industrial development of a new America. Whereas people of color — we came here as migrant workers, to work the fields. We were not exposed to those skill sets that Europeans coming from England and Germany had at their disposal. Then they also drive a wedge between poor whites and rich whites, telling poor whites to believe that if you work hard enough, you can also make it, because you’re one of us. They don’t push that same narrative when it comes to Black and brown people. They tell us, “Yeah, if you work hard enough, you can accumulate wealth,” but they don’t give you the tools or the resources to accumulate that wealth. And the wealth is usually dominated and controlled by a certain percentage of the population that doesn’t look like you.

Washington: America is infused with myths and mythologies. What are some of the things about this mythology that you think need to be corrected?

Fenelon: Probably the biggest one, and it contributes a lot to the dismissal of genocide, is that the colonists had to destroy the Indian nations — not just their claim to sovereignty, but their actual claim to the land. You can’t develop this myth of the Promised Land and the wilderness and all the rest of it until you’ve destroyed the relationship to the land of the existing people. I often use George Washington as an example, as the archetype founding father. He does all these wonderful, brave things, and he does Valley Forge, and he probably got caught on that cherry tree or whatever it was.

But after the Revolutionary War, he has to destroy one of the most advanced social-political confederations — the Iroquois League. So what does he do? He sends an army with specific orders to destroy the Onondaga: Burn their towns to the ground, kill all of their animal life, cut their fields to pieces, and probably kill a lot of them. And as the soldiers are doing this, they’re actually noting in their logs, “My gosh, these people live in homes better than ours.” This was the most advanced socio-political configuration on Earth, and Washington destroyed it to make the country stronger. They were destroying all the models, you know? Nobody talks about that. The Onondaga and some of the other peoples’ name for George Washington is “Town Destroyer.”

Washington: These myths that we have, not only of certain races, but of classes of people that are marginalized — what are some of those myths that need to be exposed?

Reisman: The stories of exceptionalism and triumph draw a clear line of continuity. But with most of the bad stuff, there’s a break, right? Bad stuff always happens in the past. So when you have Native people saying, “But this is our land; we still live here. We’re literally alive and here” — it’s distant, right? It’s like, “Wait a minute; I thought that was in the 19th century. Didn’t we all read that Wounded Knee was the last battle? It’s all done after that, right?”

Some of the work that needs to be done is excavating the lines that connect past and present. I was recently reading Craig Wilder’s book Ebony and Ivy. He documents the money, the profit from slavery, that funded all the Ivy League schools. That’s not something you learn in high school, right? You learn, “I need to get the grades so I can go to these Ivy League schools,” but you don’t learn that their wealth comes from the slave trade. I think the history classroom has an obligation to connect these lines between past and present to help students see the route of their lived experience.

Dell’Angelo: A part of history that I think could be taught better is the Great Migration and how folks came to the North. Growing up in South Philly, I was definitely one of these kids who were like, “We’re enlightened, you know? We are the Northeast of the country.” And then I learned about the Great Migration and how when folks came up here, they had no choice about where they’d live; there was mad segregation in terms of where people were allowed to live and how much rent was charged.

We created a system in which people had to live in very narrow areas, and when they tried to move out, it wasn’t just white flight — it was terrorism. People’s homes were burned down; people were threatened. So we’ve created this de facto segregation, and then we look at groups of people and say, “Oh, why are you not venturing out?” I think there is this feeling, especially for people in our part of the country, that we somehow are above this, and actually, we’re not. In New Jersey, right over the bridge, there’s, like, 600 school districts. That many districts exist because so many communities drew little circles and said, “I don’t want my kids to go to school with those kids.”

Jimenez: I think we need to dislodge the standardization of what it means to be human. A lot of the Eurocentric conception of “This is what is normal, this is what’s right, this is what it means to live civilized” — that same narrative is still perpetuated today. So we see folks measuring and saying, “This is what a good neighborhood is; this is what a bad neighborhood is,” divorcing it from the racialized structures that this society has developed and maintained and still perpetuates. And then we turn around and be like, “Oh, well, what’s wrong with those people? What’s wrong with you?”

I always emphasize that when Martin Luther King was talking about all people, he was talking about all people. It wasn’t like Thomas Jefferson saying all men are equal and just meaning a certain small measure of whatever-age white men. It becomes a whole nother story.

We need to dislodge our Eurocentric conceptions of what it means to be human — what is normal. We’ve kind of gotten stuck in this paradigm of Western civilization where a society is a third-world country unless they have the measures of industrialization we have, ignoring the fact that the levels of industrialization we have are killing us and are unsustainable in a larger picture of things.

I always get concerned where I turn on the TV and people are like, “Everything’s better now. All you’ve got to do is stop being mad. All you’ve got to do is start getting along, pull up your pants, stop complaining. Look at Barack Obama, right?” And then at the same time, implicitly, we’re saying, “What’s wrong with you, ignoring the fact that in America, we’ve got children killing children over crumbs?” There is a huge, growing split. And the measure of a person’s worth is just the length of a coin. When we have this reality, I would argue it leads to a sense of meaninglessness. The very core of the mythology that needs to be addressed is: What is considered the norm in the development of society, in the development of humanity, and in the development of our identities?

Reisman: This idea that things always get better — this kind of teleology that “Yeah, it’s bad, but … ” Suffrage in Pennsylvania is an example. There was broader suffrage in the 18th century, and then in the 19th, it was constricted. People are so surprised about LGBTQ rights — “We have marriage now; they’re not going to go back.” Well, your stock goes up and it comes down, and not to prepare students for that truth — that African Americans, for example, in the 18th century in many places had more rights than they did in the 19th — I just wanted to highlight that point. Because it’s not just connecting past and present; it’s also preparing students that nothing’s given. This notion that we’re on some kind of teleological journey toward better and better is patently false. But that doesn’t fit our story arc, because that’s not a good story.

Washington: We always hear this phrase “not in my backyard,” or NIMBY. Around the table this morning, we’ve talked about a different version of this: “It’s not my problem.” Every generation says it’s not my problem, although they benefited from the prior generation. How do we attack “It’s not my problem,” through curriculum or through social action?

Dell’Angelo: That’s a hard question. It’s messy because it’s not what people want to hear — it doesn’t fit into the narrative. So as an educator, I also have to be willing to be uncomfortable, be willing to get called in, be willing to have students or their parents tell me I’m trying to indoctrinate them. I have to be ready for that and be willing to constantly be calling people into a conversation that’s going to continue to be messy. I think that’s hard for white folks, for people who can just tap out, because they could easily just leave the work to people who have no choice but to fight every day.

Jimenez: I taught in the school district for 12 years, and the one thing I learned as a teacher is that education is a two-way street — that you have to learn from your students as much as your students learn from you. And if you’re not learning from your students, your students aren’t learning from you. In my new role as a social studies curriculum specialist for the school district, I’m trying to approach curriculum that way — in a way where teachers are exposing students to critical information.

A lot of people say, “Ignorance is lack of knowledge.” No — ignorance is the presence of something; a lack of knowledge is something, is present. We’re dealing with a lot of situations now where most of us have been indoctrinated by this system on what is considered normal, and it’s a whole process of thinking, of unlearning. It’s not like you’ll reach the same conclusions that I have through my journey and my struggles and my interpretation of what I have taken in. But you will have to wrestle with certain fundamental questions about what it means to be who you think you are.

I was telling James and Abby about how we’re revising the world history curriculum in the district, trying to take it away from this Eurocentric narrative of caveman, the Enlightenment, the New World nonsense, and really look at themes relating to deeper ideas. There is no reason why teachers should think, “Here’s a textbook; this is the curriculum.” That’s not the curriculum; the curriculum is all the resources and stories and everything that you’re demonstrating and showing to the students. So curriculum can be used as a tool to ask those fundamental questions — not to tell students the conclusion, because we will reach different conclusions, but a way where they can start to ask those fundamental questions.

Too often, we want to tell children, “This is who you are; this is what it means to be who you are.” And it’s like, yeah, that might be true for that child, but what about that child? Our children in our schools are becoming a much more linguistically diverse, culturally diverse, racially diverse group of people. And when we’re trying to come up with a collective mythos and story line, it needs to be rooted in that critical questioning about where we have been, where we’re at today, and how do we move forward. Not move forward in the sense of some utopian-type future, but in a way of like, “What we’ve been doing is a hot sloppy mess, and we’re not heading in the right direction.” I think we fall victim to the idea that somehow, we’re headed in the right direction — if we just keep on pushing forward, we’ll get to the Promised Land. And I think ultimately, that has led our children to be very confused, because that Promised Land has been translated into this idea of what we own, what material possessions we have. And that ultimately leads to meaninglessness. A curriculum’s whole point can be just to develop the real questions that we need to fundamentally ask as a collective and as individuals about what it means to be where we’re at right now.

Washington: Abby, much of your research relates to teaching from historical documents. How does that relate to the curriculum?

Reisman: The textbook is an artifact, right? A textbook does reveal a lot about the time that it was written. You can compare textbooks from the 1950s, the 1980s and 2010, and you’ll see three different versions. That’s not because the history really changed.

What I’m talking about is just one step beyond that. The question becomes: What’s the lesson structure? Especially if I’ve got, like, 42 minutes, what can I do? Well, one lesson structure is to just give kids some background knowledge about a particular topic. Pose a question that seems very innocent: “What happened at the Boston Massacre?” Or, “What was George Washington’s policy toward the Iroquois?” Then the idea is, you find the path. You read the textbook, and you’re like, “Oh, okay, here’s the answers here.” And then you take another document, a primary source like a letter or a diary, and you “Open Up the Textbook” — O-U-T, right? It’s a great term because you’re literally opening up the textbook and challenging the account. And just by doing that, just by juxtaposing two documents, you help students see that there is no authoritative text on what happened in the past — that the work of constructing a historical interpretation requires corroboration across different sources.

When you juxtapose those documents for students, they’re forced to ask the question: “Wait a minute; why did the textbook take out these words? Why did the textbook not feel comfortable with this narrative?” Why are we comfortable shifting the story of the Boston Massacre, say, to include a Black man, Crispus Attucks, but not to tell the whole truth about how race was constructed at the time? All these questions are about memory — memory and stories of who we are and the stories we want to tell about where we’ve come from.

Washington: James, your thoughts?

Fenelon I think it’s a great place to start. There’s always a way in, no matter where you are. A fourth-grader is going to ask this question: “Where did the Indians go?” Well, you’re in it now — where did they go? You say, well, some of them went out to Oklahoma. “Why did they go there?” Some of them are stuck up in Wisconsin; some of them hid out in Canada because it was the only safe place for them; some maybe stayed here. Ask this question, and you can build the curriculum from it. But the curriculum is going to be different depending on who those people were. You can have that story in California, and you can have that story in New York.

In this area, with the Lenape, you actually have a formal removal of people. The very first treaty made by the United States is the Treaty of Fort Pitt, with the Delaware. That’s another name for the Lenape people, and that’s a story in and of itself. But why are you making this treaty in Fort Pitt, which is not their traditional lands? Their traditional lands are right here where we sit right now, all the way to New York, New Jersey, most of Pennsylvania. So then you’re at the fourth-grader question — “What happened to them?”

There’s a famous sell-out in the Walking Purchase. Penn’s sons twisted that agreement all around to get the land-corridor base from Philadelphia to New York — the most valuable piece of turf in all of the New World. So they get that, and once you have that, Indians are a hassle, right? So they just start doing softer versions — if there is such a thing — of ethnic cleansing.

By the time you’re headed into the French and Indian War — I had thought that the Scalp Act was primarily out of Massachusetts. It turns out that Pennsylvania’s deputy governor, Robert Hunter Morris, crafted the Scalp Act partly at the request of Benjamin Franklin, and with the direct military assistance of George Washington and others. It’s kind of like they said, “Well, we’ve still got a lot of Indian people west of Pennsylvania; let’s just clear the Susquehanna Valley.” So they called for the scalps, offering bounties, and it’s perfect race, class, gender: You get the most for the scalp or body part of a male, and you get less for a woman and even less for a child. That tells you exactly what they were doing. That act was passed by the Pennsylvania colonial government right here, and it kind of blows your mind. So wherever you are, ask this question: “Who were the Indigenous peoples here?” And then be truthful and ask these historical questions.

Washington: Wilfredo, how do you suggest we tell a more accurate history?

Rojas: I remember in Philadelphia, you had four churches on the same corner. If you were Irish, you could only go to the Irish church; if you were German, you went to the German church; if you were Polish, you went to the Polish church. And if you were Slovak, you went to the other church. So we split up into different ethnicities. So the question is: How do we begin to break down the stereotypes? You do that through the children, and you do that through the educators; educators have to lead the fight. It’s not a kid problem — it’s a parent problem. That’s why we have this division.

Washington: Tabitha, how do we educate educators to make changes?

Dell’Angelo: A lot of teacher-ed programs are trying really hard, right from the jump, to make sure that new teachers are equity-literate — that they are able to recognize inequity and redress it when they see it, that they know how to bridge to resources, that they’re involved in a lot of self-reflection, a lot of what was described as — it’s not my term, but the idea of “decolonizing the curriculum.” We need to do that at the college level, because if we just re-create the status quo but then say to our future teachers, “You go change the world” — that’s not going to work. As teacher educators, we need to be engaged in critical self-reflection and decolonizing the curriculum, recognizing whose voices aren’t being heard and making sure they’re a big part of the curriculum.

Jimenez: I’m very encouraged by the increase of whiteness studies — of looking at whiteness in a more critical way. I think that folks need to realize your whiteness can create an issue when it comes to teaching the non-white students right in front of you.

For teacher educators, the number one thing they need to focus on with their students is exposing them to material and concepts and theories that dislodge normalized whiteness and dislodge this idea of the progress of humanity. That idea of progress is based on definitions developed by Eurocentric imperialists. They use the study of cultures to justify: “Well, our culture is the most advanced; measurement is based on my definitions of what it means to be advanced.” We still operate from that premise, even if we don’t want to admit it.

Audre Lorde has this quote — “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” I’ve wrestled with this heavily, because I work closely with our district’s equity office in developing trainings on decolonizing the curriculum — it’s literally our whole thing. But when we talk about the idea of decolonization — within itself, that’s a form of violence against the current structure that exists. And that usually leads to backlash, because fundamentally, you’re saying, “The very foundation of what you tell yourself can’t exist anymore.” And that becomes a threat to anybody who feels like they need to hold on. That’s why you see situations where it’s a zero-sum game: “Oh, so the more they get, I get less.”

But that’s the mentality of scarcity that is rooted within this culture — that we can’t exist simultaneously with contradictory ideas while accepting the nuances and the differences that exist among us all. Instead, it becomes, “Yeah, we can accept the differences, but you’ve got to look like us, you’ve got to dress like us, you’ve got to act like us, you’ve got to live in houses like us, you’ve got to have the same type of motivations and goals and dreams as us.” And it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of unsustainability, because those houses, those victories were gained from the exploitation of the majority of the world’s people.

Reisman: Ish and Tabitha identified two things that are essential in the development of teachers to do this work in history classrooms. One is their own identity work, which is absolutely ground zero. Two is curricular resources that allow them to do rich history with students. But three is the capacity to open discourse in the classroom. If you have one and you have two but you don’t have three, it’s not happening in the classroom. Teachers might go out to drinks with their friends and have deep conversations, but they’re not doing it in the classroom with kids. So what does it mean to open discourse in the classroom? I think there’s a few things it requires.

It requires, first of all, not assuming that you have all the answers, even if you studied this stuff and you’ve read extensively. If you come in thinking that you have the story to tell kids, maybe you’re very engaging and they’re going to listen to you intently, but they’re not going to retain it — they’re not going to hold on to things that are going to make it theirs. It requires being genuinely curious about what kids are saying — not just pretending to be curious, but actually, legitimately being curious, so that when you say, “Tell me more, explain a little more. What do you mean?,” they know you’re real, that you’re really, really curious about what they’re saying.

I think it also requires seeing kids as resources for each other, which is part of decentering oneself as a teacher.

Dell’Angelo: You’re so right, because the research says that no matter what we do in teacher ed, most teachers re-create their own K-12 experience. And why wouldn’t they? They think, “I don’t want to take risks unless I’m sure I know what I’m doing.” But maybe there’s also this need to accept and expect some failures and be okay with that and fail along with your students and say, “I don’t have it all figured out. Let’s figure this out together. Let’s talk about this.” But it is scary, right? Because it requires risk-taking, and if we don’t support that at the teacher-ed level, it all falls apart.

Reisman: And that’s a cultural norm you can set in your classroom — be like, “We’re a class of learners.” Let’s say one student makes a claim that’s problematic. You can have another kid, their peer, being like, “What’s your evidence?” And then as the teacher, you need to be prepared with resources — but also to create a culture where it’s like, “I’m going to be so proud of you this year if I hear you say, ‘I hadn’t thought of it that way,’ or ‘Oh, wow. Now I changed my mind.’ If I hear one of you say it authentically, that’s a sign of learning. There’s no shame in that.” So it’s about creating a classroom culture of learning, of discourse, of respect, of no shame. I think that’s the work for our present times.

Washington: Let’s get into a lightning round: What’s the purpose of teaching history, Abby?

Reisman: There are different models out there. There’s the model that says the purpose of teaching history is to sweep people into a national patriotic narrative. It’s a construction of statehood — that’s sort of the oldest version of it. There’s a version that I’m more aligned with, which is that it’s about getting kids to think critically and construct interpretations, to understand how they want to tell their own story. It’s the investigation of questions with evidence.

I think the purpose of studying history is to foster humility. I think it’s to help people understand that they are historically constructed. That the way we see each other, through all the levels of translation that we’re doing as we look at each other and categorize and figure out — that’s all historically constructed. To take that in, in a deep way, is to be humble about what we believe to be true.

Washington: How can we better expand upon history where we get into gender, class, sexual orientation?

Rojas: A lot of times, the history that is written is not written by us. So those who write our history get to tell it from their perspective and from their mind-set. So it’s important that we document our histories, even our own personal histories growing up, so that people know we’re keeping a running record of what has happened to Black and brown people and Asian people and Native American people and LGBTQ people. There’s a lot of interesting history there, but again, it’s usually written by someone else and not from our perspective — the people that are really living it in the flesh.

Washington: As the phrase goes, those who hold the pen control history. What can we learn from other countries? Are other countries doing better at this than we are? South Africa had their Truth and Reconciliation Commission that was, to borrow a phrase from Bill Barr, B.S. People came in and confessed and then walked out without being held accountable for their crimes.

Jimenez: It’s interesting you bring up South Africa, because there were uprisings and riots there last summer, which is a reflection that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission wasn’t really reconciling or speaking truth. The majority of land is still in the minority white hands. The leadership might be African, but the structure of the system does not benefit the average person.

I think that’s where class becomes involved. We’re very America-centric — everything floats around us. In the rest of the world, you’re having an issue now where the desire to replicate what has been created here becomes a class issue in a lot of places. You might have the ability to wax philosophic about the meaning of our existence if you have privilege in those societies, but the majority of people don’t. The majority of people have to live on less than $2 a day, and South Africa’s an example of that. What we’re seeing in Ukraine and Russia and all these other places around the world right now, in North Korea, we’re seeing the long, drawn-out results of competition over desired resources by elites.

What we need to be doing with students is involve them in those conversations, across the world, across classes, across gender identities, across racial identities, across languages. This is the first time in world history where we can talk to somebody in a completely different language, on the other side of the world, in real time, where they understand what we’re saying and we understand what they’re saying. We need to take advantage of that so we can speak about what we really, truly need to be doing.

Fenelon: We could learn something from the very painful discussions that Canada’s had on its boarding schools. You can go right down the road to Carlisle to get a pretty good example of it here. When they discovered those mass graves of students, Canada had to go through an incredible introspection. There’s no denying that people were wrested violently from their cultures for the purpose of suppressing them and their knowledge and history, as well as having the language literally beaten out of them.

The United States does not want to look at itself as a country that actually farmed out reservation schooling systems and boarding-school policies to specific religious groups and specific policy constructs. We could learn from Canada, but talk about a painful lesson.

Washington: Abby, is there a book about history that you would recommend?

Reisman: How the Word Is Passed, by Clint Smith, does a really good job of talking about historical memory around slavery and what stories are told and what stories are intentionally suppressed. I think it’s a good starting place for teachers to understand historiography but also collective memory. Why do we insist on remembering certain stories and suppress others?

Washington: Wilfredo, what book would you recommend?

Rojas: War Against All Puerto Ricans, by Nelson Denis, is a chronological series based on the colonization of Puerto Rico. It’s true that right now, there are many right-wing movements in Europe. But there are a lot of left-wing movements in Latin America. Colombia just elected a leftist president; so did Peru. They have them in Venezuela, Cuba, Nicaragua. So there’s a shift in Europe to the right, but there’s a shift in Latin America to the left.

Dell’Angelo: A great book is The Warmth of Other Suns, by Isabel Wilkerson, because she is a storyteller. You can almost think it’s fiction, but it’s nonfiction, and it’s about the Great Migration.

Jimenez: One of the books I’ve read that’s really good is Fugitive Pedagogy, by Jarvis Gibbons. It goes over the history of how African Americans taught their children despite it being illegal. I think it’s just a beautiful story line, because it teaches us that the attack on teaching true history is a consistent theme in America, and there are examples of people and how they combat it.

Washington: How do we counter the opposition to teaching true history?

Fenelon: I go after this word: ignorance. Ignorance suggests I am ignoring something — are you ignoring this whole other discussion? People probably are not consciously ignoring this whole other set of histories. I really realized that when I decided I had to address the 1619 Project. As powerful as 1619 is, it doesn’t seem to be seeing the Caribbean issues that preceded its bigger issue.

Dell’Angelo: Part of it is this idea of reclaiming terminology. So the idea of indoctrinating children, which we hear a lot — my understanding of the idea of indoctrination is withholding information. And we have for more than 100 years been withholding the full story from our American public-school system. What has been mentioned a few times today is, “Okay, here’s the story. Let’s look at the original source; show me your evidence.” I’d be hard-pressed to think any parent doesn’t want their children to be able to use evidence. So this idea of alternative facts — there are no alternative facts. So this is what you believe? Show me how you’ve made that logical step, whatever it is. I think we need to reclaim that narrative, because schooling’s purpose has been to maintain hegemonic structures, and we have to acknowledge that and push back on it. But we have to be savvy. There’s got to be this dance between force and finesse.

Although now that I’m saying that, I’m thinking about people who talk about pacing for privilege — like, we can’t just baby-step to make people comfortable, because there are people who are never going to be comfortable. So anytime people are ready to move, we’ve got to move, and the middle will come along with us, and some people were never coming anyway.

Jimenez: And that just makes me think: If we really look at history in this country, we have to be honest about the political reality that existed. People were so shocked that somebody like Donald Trump got elected, and I’m like, “You live in America, right? You know what this is about?” So I think operating from an honest perception — we’re not going to move everybody, but we need to create structures and institutions where we can perpetuate spaces where folks can do this, spaces for folks in the organizational spaces that we are part of. But at the same time, we need to recognize that you have to be courageous, because ultimately, at the end of the day, you’re going to receive pushback, and if you stop receiving pushback, then you ain’t doing it right.

Washington: Wilfredo, I’ll give you the last word. What kinds of strategies do you have to push back on the pushback?

Rojas: I think we have to meet people where they’re at. We’re not going to be able to change a lot of hearts and minds, but we have the facts on our side, and we can prove our facts, and we’re logical in our thinking. They’re listening to some puppet master who’s telling them what to say, even though they won’t admit that. By using facts, we can wear them out, because they can’t refute facts. They try to make up facts to buttress their argument. But we have the true facts, because we research it, and a lot of us have lived it. It’s difficult, but you know what? Nothing comes easy. If you don’t work and fight for something, it’s not going to happen.

The Panel

First row, from left: Washington, Dell’Angelo, Fenelon. Second row, from left: Jimenez, Reisman, Rojas. / Photography by Colin Lenton

Linn Washington Jr. is a journalism professor at Temple University. He has extensive experience reporting on and researching issues involving race and racism.

Tabitha Dell’Angelo is a professor of education at the College of New Jersey. She co-edited an award-winning issue of The Educational Forum titled “Educator Activism in Politically Charged Times” and has written and presented research on decolonizing K-12 social studies curricula. She currently serves on the school board of the Central Bucks School District.

James V. Fenelon, the Lang Visiting Professor for Social Issues at Swarthmore College, works and writes in the fields of Indigenous studies, racial/ethnic relations, urban education, American Indian history and Native nations. His social justice work has taken him to numerous Indian reservations and many countries, including Haiti, China, Japan, Denmark and Malaysia.

Ismael Jimenez is a longtime African American history teacher in the Philadelphia school district, where he currently serves as a social studies curriculum specialist. A graduate of Temple University, he’s also an adjunct professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

Abby Reisman is an associate professor of teacher education at the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education. Her research centers on the challenges of teaching document-based historical inquiry, with special attention to supporting teachers in eliciting and facilitating student discourse. She began her career in education as a classroom teacher in a small, progressive high school in New York City.

Wilfredo Rojas is a longtime civil rights activist and the founder and retired director of the Philadelphia prison system’s Office of Community Justice and Outreach.

Published as “See No Evil. Hear No Evil. Teach No Evil?” in the September 2022 issue of Philadelphia magazine. This article has been corrected to address an error in its description of Robert Hunter Morris.