Inside Jim Kenney’s Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Year

When he was first elected in 2015, Jim Kenney seemed like the perfect mayor for the moment. Then COVID struck, and the moment changed. Will the pandemic ruin what’s left of his legacy, or is there still time for him to bounce back?

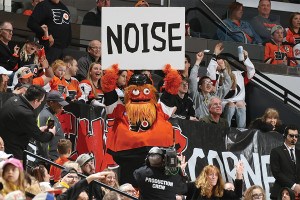

Photograph Courtesy of Chris Leaman.

“There is a finite period of time for each of us to make a positive impact on our city as elected officials,” Mayor Jim Kenney said on March 5, 2020, at his fiscal year 2021 budget address.

He said this by way of officially welcoming new City Council members Kendra Brooks, Jamie Gauthier, Katherine Gilmore Richardson and Isaiah Thomas to Philly’s local legislature.

Nearly two years later, when you watch the video from that budget address, it’s hard not to think these six syllables: super-spreader event. Council chambers seem even more tiny and poorly ventilated than they are. When you look out over the audience, you can witness people standing next to each other, sharing moments, sharing air.

Seeing City Council chambers packed like that feels not unlike watching old 1950s TV commercials with doctors smoking cigarettes in their offices.

And just as the ’50s may seem idyllic in our revisionist memory — for some of us, anyway — the time before COVID can feel like a golden age. In March 2020, George Floyd was still a father and resident of Minneapolis. Nearly 4,000 Philadelphians were still your neighbors and not yet statistics on the city health department’s COVID dashboard.

In November 2019, just a few months before that budget address, the people of Philadelphia reelected Jim Kenney with 80 percent of the vote. It wasn’t exactly a feat: No mayor who’s run for reelection has lost since the local constitution, the Home Rule Charter, was adopted in 1951. And only twice — Goode/Rizzo in ’87 and Street/Katz in ’03 — were the races even close.

Jim Kenney posing for a selfie with Hugh E Dillon after being sworn in for his first term. / Photograph by Joseph Gidjunis / City of Philadelphia

Kenney’s budget address, then, wasn’t the culmination of a hard-fought political campaign. In the crowded 2015 Democratic mayoral primary, Kenney had clearly received a mandate. This was something different. It was pointless pomp that could have been and — given Kenney’s default bone-dry oratory — probably should have been just emailed into the record.

This was my fifth budget address since I’d left journalism to become an administration spokesperson. I was over the theater. Once I had the prepared remarks in my hands, I knew where this address was going. Things had gotten so formulaic and boring even to me, a Jim Kenney appointee, that I didn’t attend that year.

Don’t get me wrong. I was still inspired by Jim Kenney — though I never in my life found myself inspired by a Jim Kenney speech.

It takes a special kind of person to make wild success boring, but think about it: In March 2020, Kenney was indeed a wild success. He’d artfully negotiated with every labor union the city did business with. He’d reversed many of his predecessor’s painful Great Recession austerity cuts. His vision and leadership brought schools under local control and solidified the power of Philadelphia’s already imperious mayoralty with a mayor-appointed, not popularly elected, school board. He’d delivered crucial funding for pre-K by getting Council to pass the nation’s first big-city sweetened beverage tax, known by proponents and detractors near and far as “the soda tax.” He received national attention for standing up to Donald Trump.

Yet in four years, he went from holding a bullhorn at the airport and telling immigrants they were welcome here to mere background noise on Action News. If you compare his 2020 public schedule to 2016’s, you’ll note the decrease in appearances and the near-total absence of events in the morning. In 2016, there was, apparently, some hope he’d leave the house on time. Staff in 2020 knew better.

Still, with those first-term accomplishments as the foundation, the plan for a second, as laid out in that March 2020 budget address, read like a progressive wish list: expanded public-education funding, free community college, criminal justice reform, all buoyed by sky-high city tax receipts and population growth fueled much more by immigrants than by a relatively small number of bourgeois millennials.

That budget address even included, along with progressive police reforms, some braggadocio about homicides being down 17 percent from 2019 in certain key areas, and an unspecified “significant decline” in shootings.

These were heady times. The sky was the limit.

Nobody had any idea how much all of this was about to change.

“His heart is always in the right place. and his head, sometimes … is in the place these messed-up situations take all of our heads,” states Ajeenah Amir, Kenney administration staffer.

When I worked at City Hall, I was two steps from Kenney’s direct report in the Mayor’s Office. I had heard that things grew a little more difficult, the clouds overhead a bit darker, the closer you got to him. I jokingly referred to him as “Dad” around the office. “I’m worried about Dad,” I’d say if he looked particularly morose.

I was “worried about Dad” kind of frequently in retrospect, especially toward the end of my tenure. If first-term Kenney was a beloved gruff uncle, executing an ambitious progressive agenda against the backdrop of a successful city, the machinery of government whirring along as expected, second-term Kenney was an avatar for our city’s post-Trump COVID malaise: numb, rudderless, and — like the garbage that continued to pile up around us — uncollected.

Photograph Courtesy of the City of Philadelphia / Joseph Gidjunis

Recently, I’ve been reaching out to my former co-workers and contacts — and the Mayor himself — to figure out why his mayoralty feels so … adrift. I talked to about a dozen people, some on the record, some off, all of whom seem to confirm the same thing: Kenney was a mayor perfectly suited for Philadelphia in 2015, even if he seems out of step with the needs of Philly in 2021. From COVID and gun violence to opioids and housing insecurity, events inside and outside his control have combined to threaten his legacy and overshadow the tremendous successes of his first term.

But while Kenney may be a victim of bad historical timing — any mayor during COVID has faced unprecedented challenges — it’s his earnest virtue-turned-vice humility and low-key aloofness that seem most likely to imperil his legacy. Whether it’s the so-called life of service that Jesuit educators inculcated in him or something more related to his personality, he’s in critical danger of Philadelphians becoming as unenthusiastic about him as he seems to be about, well, everything.

“His heart, I feel like, is always in the right place. And his head, sometimes … ” Longtime Kenney administration staffer Ajeenah Amir pauses, reflecting on the terrible nature of 2020 and its myriad tragedies. “Is in the place these messed-up situations take all of our heads.”

For years, the Mayor’s staffers joked that there were two Jim Kenneys: “glasses-on” and “glasses-off.” With “glasses-on” Kenney, you were hearing “the Administration” as though it was some progressive life force, a voice from on high.

“Glasses-off Kenney,” on the other hand, was the more prophetic. With glasses off, he showed his anger, his sadness, his love. It was when the waterworks burst forth. In other words, it was when you found him compelling. It’s where his Twitter reputation, once the talk of the town, came from. (“So sad sometimes,” reads Kenney’s most relatable tweet ever.)

“I think we’ve been very successful in a very difficult time,” Jim Kenney tells me. The Mayor, the glasses-on version, is speaking to me on the phone on a cold, rainy autumn morning three years after I left the Mayor’s Office, eventually returning to my career in journalism.

“I mean, obviously, the first term was very challenging, as all first terms are. But I think the things we’ve accomplished are worthwhile and made people’s lives better” — he hesitates, presumably to take his glasses off — “and will, I think, continue on after I’m gone.”

The notion that Kenney views both his first term — replete with impressive policy wins — and today, in the still-churning wake of COVID, as “challenging” speaks to the man’s signature Ron Swanson-style misanthropy. One random day several years ago (no breaking news, no behind-the-scenes drama), I walked by him and asked how he was doing. “Worst fucking day of my life,” he said.

Kenney with school superintendent William Hite distributing meals for students of just-closed schools in March 2020. / Photograph by Monica Herndon/ Associated Press

The challenge of his first four years included the excruciating fight for that term’s signature accomplishment, getting Council to pass the Philadelphia Beverage Tax. While not the “nuclear bomb” of COVID, as Kenney refers to the pandemic, the fight was bloody. But that tax is likely to be one of the most progressive, successful initiatives in Philadelphia history. And it was Jim Kenney, reluctant, low-profile mayor, who orchestrated it.

The tax, while still controversial, is a moneymaker and has, to date, provided 10,000 kids free, quality private pre-K, connecting students to reading and math and giving parents the ability to go to work instead of worrying about childcare. As a bonus, it supports programs provided by a mostly Black, mostly female slate of small-business owners.

“The result — thousands of Philadelphia children with access to free, high-quality pre-K — will be felt for generations to come,” says longtime political consultant Mustafa Rashed, a principal with Bellevue Strategies and the insider’s insider. Since mayors here are limited to two terms, he explains, they will often try to accomplish something popular, with an immediate benefit, in the first term to help them win a second. “Millions of dollars were spent to make the beverage tax unpopular, so to go up against that was significant. That was the courage of the beverage tax — that the benefits wouldn’t be felt for at least a decade into the future, long after Mayor Kenney’s political career has ended.”

In his first term, Kenney also slew the School Reform Commission — the state body that had snatched control of education in the city two decades ago — and brought Philadelphia’s public schools back under local control. And he’s dramatically increased the city’s contribution to its own school district by $151 million, or 145 percent, since the beginning of his administration.

Criminal justice reforms, supported in part by the MacArthur Foundation and helped significantly by the presence of District Attorney Larry Krasner, who’s notably stopped seeking cash bail for low-level offenses, have reduced the local prison population by 43 percent.

While the city’s fund balance is still dangerously low, economists and the city’s own director of finance, Rob Dubow, say pensions are on track to be fully funded by 2033.

“My legacy will be judged in the coming years,” says Jim Kenney. “And I’m fine with that.”

With Kenney as mayor, the days of constant fighting between City Council and the chief executive that were seen during his predecessor’s tenure are gone. Most bills sail through the legislative body with near-unanimous agreement — after all the wheeling-and-dealing takes place.

Let’s not forget Kenney’s successful shepherding of major public events ranging from Hillary Clinton’s DNC to the NFL draft and the Eagles’ Super Bowl parade. Oh, and the loathed wage tax is back on a downward trajectory.

Kenney, with Governor Tom Wolf, speaks at the Eagles’ Super Bowl parade. / Photograph by Samantha Madera / City of Philadelphia

These are big things. But they’re no longer the only things.

“For everyone,” says Ajeenah Amir, “you meet the times or the times meet you.”

Amir spent years as one of Kenney’s spokespeople and until recently led the Mayor’s Office of Public Engagement. “What I definitely believe about Jim Kenney is that he has tried his best to meet the times and to operate with integrity and tried to stay on course for the same reasons that he became mayor,” she says.

But despite the wild success of his first term, and even the qualified success of his second — the city, despite it all, is still standing, no? — is Kenney’s best good enough for this moment? More to the point: Is his low-key everyman tendency actually a liability when we need a hero, a cheerleader, a mayor?

If you’ve been down on Jim Kenney for his response to COVID, for the summer of 2020 incident on the Vine Street Expressway, for the surge in gun violence, know that Jim Kenney is right there with you. And the past year has taken its toll on the man, mentally and physically.

“You try to put a hard shell on,” he says, admitting he’s not a hard-shell person. “I do internalize a lot of the stuff. I do get frustrated.” He goes on: “I don’t sleep very well. It does have physical effects. You kind of — not second-guess; you internalize it and come up with all these different scenarios.”

Relatable.

“Jim Kenney is his own worst critic,” says Louisa Mfum-Mensah, Kenney’s shadow from halfway through term one until March 2021 as his special aide and liaison. During COVID’s emergence and quarantine, she was his constant sounding board.

“He’s often in his thoughts about what he’s decided, which is why to outside parties he can appear grumpy or unhappy,” she explains. She’s a warm, joyful person who doesn’t take anybody’s shit, including Jim Kenney’s. “But Jim is one of the kindest and most thoughtful people I know.”

It’s an odd pairing, a 30-year-old Black woman who emigrated as a child from Ghana to Canada and then found herself a Philadelphian and a 62-year-old white guy from South Philly who, in 2014, tweeted in disbelief that journalist Leslie Stahl, at 72, was “smokin.” “GTFOOH!” he exclaimed.

That tweet played into a larger belief that Kenney’s just a regular guy. Yet when he sent it, he had been an at-large member of Council for more than 20 years. His calls were answered immediately by every journalist in town, including this one.

And maybe that’s the problem: Jim Kenney sees himself as a regular guy, but he’s not. Perhaps he never wanted to do all the pomp and circumstance that come with being mayor, but in times like these, pomp and circumstance matter.

In 1992, Ed Rendell cannonballed into a public pool to become, probably, the first mayor in Philadelphia history to be photographed shirtless. Stuff like that made him the story. He was like the Phillie Phanatic: a curious weirdo willing to do anything to keep people’s hope alive. More than that, he was our weirdo.

Unlike the Phanatic and Ed Rendell, Kenney wants to blend in, to be behind the folks in the picture at the ribbon-cutting. Everyone else deserves the credit, he insists.

That’s all well and good when there’s credit to go around. But when things are bad, fading into the background isn’t an option for the mayor of one of America’s largest cities. In these troubled times, people need a leader. They also need inspiration and hope — not the chilly humility Kenney offers while focusing on big-picture policy with a 30-year payoff.

After all, sometimes small-picture policy goes a long way. Rendell’s pool publicity stunt had a purpose: It showcased the work he’d done to get the public pools open and signaled that after near financial ruin, the city was breathing again — and that neighborhoods, not just balance sheets, mattered.

By contrast, Kenney was the one in charge when several public pools remained closed this summer due to a national lifeguard shortage.

Sixty miles east, Shore towns initially had trouble filling those positions, too, until they started paying the right wages — $20 an hour. Then, their lifeguard stands filled immediately. At the time, I wrote an op-ed in the Inquirer decrying the demoralization of not getting all pools open at any cost — why not push for increased lifeguard salaries? Why not spend a little time and effort on a small project that could make a big difference in the mood of the city? It was doable, if not effortless: Kenney would have to get dispensation from the civil-service ecosystem and come up with the money. Instead, he dodged the problem altogether and let his staff explain why “no” was the right answer.

For that column, I asked for comment from the administration and spoke at length with city officials, but I never spoke to him directly.

“You know, when somebody writes an editorial or something and doesn’t even call me on the phone to ask me my opinions,” Kenney says to me during our interview, “they don’t even give me the opportunity to do that and then they trash me, that’s just the way it is. I’ve gotten more used to it than I was in the beginning of the second term. I don’t remember being trashed that much in the first term.” I swear it sounds like he’s speaking through his teeth.

I’m briefly frozen. When he wants to, Jim Kenney can seem enormous, even over the phone. If he can just switch on that large-and-in-charge aura, why doesn’t he employ it more often?

After all, if someone reflexively refuses to take credit for things he’s done, after a while, you start to believe him.

“It doesn’t serve him well politically,” observes Mikecia Witherspoon, Kenney’s former special assistant (a.k.a. “body person”) and, later, deputy chief of staff. “As a former employee, I thought his humility was great, because he gives credit to those around him who truly do the work day-to-day. As mayor, the perception is that you’re the reason for the wins and the failures. If you’re too humble, Philadelphians won’t give you credit for the wins — they’ll be quick to make you answer for the failures, though. It’s lose/lose.”

The ability to put on a cheerful face and do some mayoral cosplay could help Kenney take a stand against another problem bedeviling his second term — namely, that the city is seeing the effect of larger national trends, many of which don’t allow a lot of room for maneuvering at the local level. Guns are the purview of the state and federal governments. Opioids are bad in Philly and in West Virginia. And everyone is riding the COVID tiger.

Kenney at a March 2021 press conference about reopening schools. / Photograph by Albert Lee / City of Philadelphia

About those guns: Shootings in the city are at their highest level in years and have dominated the news and people’s thoughts. Homicides dramatically increased in 2020 and 2021 despite overall crime being at historic lows nationwide. Philadelphia wasn’t alone; most cities saw similar increases, with a small handful of exceptions.

I ask Kenney: What can be done? What will actually and seriously reduce shootings?

“Gun control,” the Mayor says matter-of-factly. “It’s very clear and very simple. Countries that control the flow of weapons to the public are safer than those that don’t.” The data suggests he has a point, but it’s a deeply unsatisfying answer.

Constitutionally and legally, the city can’t do much of anything about gun control.

Instead, it seems City Hall’s answer to this and other big issues is throwing money at them and cynically acting busy, with everyone at the top believing it’s so much going-through-the-motions.

“We’re doing what we can locally,” says Kenney spokesperson Kevin Lessard. “A record $155 million will be invested to reduce and prevent violence this year alone, which doesn’t even include money for traditional policing.”

A lot of the initiatives that money will be funding have scant proven efficacy. They’re not, in other words, “evidence-based.” Do they work? Who knows? Do they make people feel good? Not really, since Jim Kenney, for one, just happens to be unable to contain his demoralization at the futile exercise.

A lack of urgency or enthusiasm could also describe Kenney’s response to the protests in the summer of 2020 — the nadir of his mayoralty, when police seemingly corralled protesters into a choke point and then, when they were penned into a small area along the Vine Street Expressway, fired tear gas at them.

It was the moment that Kenney went from liberal hero to The Man — in the “stick it to” sense, not the “Chase Utley, you are” one. In 2014, then-Councilmember Kenney wrote the bill that decriminalized cannabis; he listens to Bob Marley. He’s supposedly the cool dad. Yet at that moment on 676, Philly briefly looked like Chicago in 1968. If he wasn’t a hard-core progressive, what was he? Where was his home politically after his police did this?

Even his response is passive, both in voice and tone.

“The use of tear gas in that particular case was not authorized and done by people on scene,” Kenney says flatly.

“But I’m responsible for it,” he’s quick to add.

He’s seemingly still disappointed and hurt and angry about it.

“There are lots of things going on in the midst of all that,” he says. Everything seems to slow down while he speaks.

“People found taking a highway — all these things run through your mind. Are people going to get stuck in their cars and panic and start trying to speed out of there, running people over? Is somebody going to get dragged out of their car and beaten up? What’s going to happen? You don’t know. You’ve never seen it before. And then as it plays out, you realize that things could have been handled differently.” Kenney pauses. “And you wish they were.”

So when I ask him about his biggest regret so far, I expect him to say that Vine Street incident. He surprises me.

“My regret is something we couldn’t control,” Kenney tells me after much thought, “and that’s the effect COVID-19 has had on people. The number of people we lost.

“I get frustrated right now,” he says, dispensing with the talking points and going straight for his actual feelings as glasses-off Kenney, “with people not getting vaccinated. I don’t understand why you wouldn’t. And I can’t force people to do it, but that’s frustrating.”

Can’t he force them? He could be much more forthright on the issue. He could work with Council and L&I on a mandate for local businesses. He could likely even, given Supreme Court precedent and his elected powers, require all residents to be vaccinated. In both scenarios, he could then let the legal chips fall where they may — like he did with the soda tax — rather than simply accept failure as inevitable. He could be out there every day shaming the businesses and unions that are dragging their feet. Instead, he’s still mostly reading from a script into a webcam, like he’s been taken hostage.

Despite this, the city, the CDC, a slew of marketing campaigns locally and nationwide and, frankly, common sense, among other things, have gotten, as of press time, 888,513 Philadelphians fully vaccinated and another 199,905 partially vaccinated. The city’s labor unions agreed to comply with federal and local governments’ polite requests (or requirement, depending on whom you talk to) for a vaccinated workforce — that is, except for the police and firefighter unions.

Putting aside the FOP’s bizarre refusal to protect its members against a deadly virus, Philly now has some 70 percent of adult residents vaccinated — a Biden administration benchmark for excellence, though with just 55 percent of the total population vaccinated, Philly trails the state rate by five percentage points.

“Some media outlets are still talking about silly things like Philly Fighting COVID. It’s like, ’All right, well, that was a mess-up,’” Kenney says, exasperated. “We’re one of the most vaccinated cities in the country.”

The Philly Fighting COVID debacle did, in fact, dominate the news cycle — some might argue rightfully — for weeks. The top-level bungling of the city’s critical vaccine rollout and potential mishandling of private data fueled long-standing perceptions of big-city Democrats, especially in Philadelphia, as incompetent clowns. The situation cratered the health department’s credibility at a time when it was trying to convince people to get vaccinated. It’s easy to ignore all the work that agency had already done; one scandal can — and for the most part, in the average Philadelphian’s mind, did — wipe that all away.

It can’t be fun to watch incompetence or outright malfeasance in the bureaucracy when you’re the one left holding the bag. And since Kenney hasn’t really kept up with taking credit for the good, that’s all people see.

Then there’s the trash. Kenney blamed DIY projects during quarantine at one point. But that ignores the clear strife between the union laborers and management. Why isn’t Kenney knocking down the door, kicking ass, and taking names? He might not have legal authority, but he does have a bully pulpit — he’s the goddamn mayor!

COVID-19’s social distancing measures put the city into a wartime crouch. Jim Kenney, progressive policy wonk, is now a mayor like Philly Republican Bernard Samuel during World War II, but instead of Nazis, we’re battling viruses. Quarantine was like one long air-raid drill that decimated local businesses and forced the city to lay off hundreds and scale back dozens of programs.

But it also gave permission to a man predisposed to keep distance between himself and others to maintain that distance. Public relations became more regimented and less transparent. Instead of allowing everyone to ask questions at press conferences, Kenney’s staff used COVID-19 as a rationale to tightly control who got to ask what. Old habits, comfortable if not good, came back. Think about your own life. Did your social anxiety increase? Mine did. Kenney read from a script, glasses on, seemingly for months. Was he in there?

“I’m the last person to judge my legacy,” Kenney says. “I think whatever legacy there is will be judged in the coming years, and I’m fine with that.”

So how will his legacy be judged?

“By design,” Mustafa Rashed muses to me about the nature of the Mayor’s Office, “mayors are subject to a level of criticism and scrutiny that no other elected official on any level experiences.”

Does Jim Kenney stand up to that scrutiny?

“The Mayor has an opportunity to visibly guide the city out of the economic, health and social justice impacts of the pandemic,” Rashed replies. “To show leadership during a crisis would be the most effective way to cement his legacy.”

“Politicians and elected officials have bigger egos than the normal person,” Kenney tells me, speaking about politicians as though he’s an observer and not the most powerful one in Philadelphia. “But I don’t. And I get criticized for that. Because I let people speak for their departments — because I’m not promoting myself morning, noon and night. My staff, my comms staff and others, complains that I don’t want to put myself in the forefront. And it’s just not my style. It’s not what I do.”

It’s true that’s not what Jim Kenney does. But is it what the mayor of Philadelphia ought to do? How can he truly lead us? Wouldn’t that cheerleader-in-chief, that visible optimist, take away some of the sting of big, complex national issues we can’t control but that affect our lives every day?

Back when he was the foil to Donald Trump and the end of the world wasn’t happening, Kenney’s outward grumpiness and obsession with humility were endearing. But during COVID? Now that Biden is president and there’s no Trumpian heel to Kenney’s hero pose?

Even his massive first-term accomplishments seem to fade away due to his unwillingness to self-promote. Progressives always said they wanted this kind of long-term investment in tomorrow, but plans with long-term payoffs are rarely expedient in our minute-to-minute political cycles. Joe Biden and Donald Trump both knew to connect themselves to checks people were getting. Could Jim Kenney have made a similar case for pre-K, further selling the $1,000 or more families would be getting back per month to put toward expenses like mortgages? Could he still?

“In the end, you hope you’ve done more good than not, that you’ll be remembered kindly,” Kenney tells me. “And then you can go off into the sunset.” Even his vision of this seems subdued. At least John Street still raises hell by defiantly riding his bike on the sidewalk.

Speaking with Kenney’s former special liaison Louisa Mfum-Mensah again, I ask her what his character is like. She thinks a while.

“He’s got a heart of gold and truly wants to do right by the city and its people,” she says.

That much is clear.

Whether we remember that, though, seems to be a decision that’s entirely up to Jim Kenney, whose finite period of time to make a positive impact as an elected official gets smaller by the day.

Published as “Jim Kenney’s Very Bad Year” in the December 2021 issue of Philadelphia magazine.