Jerry Blavat on Sinatra, the Mob, and the Music That Connects Us

A finger-snapping, tale-telling, slightly exhausting encounter with the legendary DJ as he prepares to celebrate his 80th birthday and 60 years in radio.

Jerry Blavat. Photograph by The Kielinskis

Celebrating his 60th year in radio, and with his 80th birthday on the horizon, Jerry Blavat — a.k.a. the Geator with the Heater, the Big Boss with the Hot Sauce — hardly seems to be slowing down. The finger-snapping Philly icon is still on the radio several days a week (his show airs on various stations), and in summer, he can be found spinning records at the Shore, including at his Margate club, Memories, four or five nights a week. Here, the Geator opens up about a South Philly that is no more, his friendships with celebrities and mobsters, and why the music still has so much power.

Your 80th birthday is coming up. I have to say, you look pretty amazing.

You know, if I’m going to entertain people, I gotta look good for them at my age. So I could be maybe a little inspirational for people who are going to turn 80 years old. I mean, God gives you your body, God gives you your brain. It’s what you do with it. And I have been fortunate in my life to make people happy, and that’s one of the great secrets of staying young. Youth is a gift of nature. Age is a work of art.

What else keeps you young?

I go to the gym almost every day. Watch what I eat. I drink wine. You know, wine is very significant. The first miracle was the changing of water into wine. If you remember the marriage at Cana, and Mary said, “Jesus, Son, they’ve run out of wine.” And he said, “Well, my ministry’s not here,” but she said, “Son … ” A son will always listen to a mother.

Do you drink wine every day?

At dinner, maybe two glasses, whatever.

I remember when I interviewed you maybe 10 years ago, you showed up on your bike. Are you still riding?

I still ride the bike. As a matter of fact, I ride all over town. I ride the Geator Bikemobile.

South Philly, where you grew up, has changed so much in recent years. What was it like when you were coming of age?

You know, the book that I’ve written, You Only Rock Once, tells you the complete story. My father was a numerologist. That means a bookmaker, and he ran into the Broadway Theater in South Philadelphia, which is no longer there. And my mother, a little Italian girl — she was the youngest of the Capuano family. And every Saturday, you were able to go to the movie after you got done cleaning, but she had to go with my Aunt Philomena, who was the older aunt. And this guy was running in away from the police and saw a seat and sat next to this little Italian girl, 17, put his arm around her. She was shocked. The police didn’t find this guy they were looking for. My Aunt Philomena smacked him, my mother smacked him, and six weeks later, she runs away and marries him. Now, in 1938, you do not marry an Italian [if you were] a Jewish fella, because that’s out of your faith. He basically was not one of the favorites of the Blavats, because he was a number runner, a bootlegger, and she now is not a favorite of the Capuanos.

It’s like Romeo and Juliet.

Exactly. The Capuanos were always dancing and singing, but me and my sister basically were looked upon as a little bit of outcasts because of who my father was. But the neighborhood was wonderful, because you knew everybody. And during the holidays, Grandma Capuano would cook raviolis and meatballs and say to any one of the kids, “Listen, go knock at the door next door. See if Mrs. Panetti has anything to eat.” So we shared, and if you stepped out of line when you were a kid in the neighborhood — “Hey, if I tell your mother, if I tell your father, you’re going to get a shellacking.” So the neighborhood was safe for everybody.

And you know, they talk about people today. They say, what’s wrong with America? We don’t have neighborhoods anymore. You knew if somebody was carrying a piece, if somebody was doing drugs — get outta here. You don’t belong in here. We’re going to kick you in the ass.

Was your old man around? Did you have a relationship with him?

They called my father “the Gimp” because he limped. And the difference between the Italians and the Jewish — my uncles would be playing bocce ball on Bancroft Street with t-shirts on, but my father, we would get picked up on Friday. It’s the only time we saw our father — on Friday when he was uptown and he would take us to the movies, me and my sister. But we would go uptown, and we’d meet him at Broad and Locust, where all the Jewish guys were. And they were dressed to the T, and then we would go into the bar and they’d be drinking scotch and soda.

Back in South Philly, they’re playing bocce ball there. They’re drinking wine. So my first impressions of what I wanted to be was that side. I wanted to do it with class and style, and that’s how I grew up. My mother taught me love. And respect. My father taught me the streets and taught me the right thing to do and the wrong thing to do.

The world has changed so much. Do you ever go back to the old neighborhood?

I do. Because they’ve got three scripts being made from the book.

So we’re going to see your life on the big screen at some point?

I’ve got to tell you what Scorsese said. Frankie Valli, who’s a dear friend of mine — you know, Scorsese was interested in doing Jersey Boys before Clint Eastwood. So [Scorcese] read my book. In it, I talk about how I was able to get the deal made for Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons with VeeJay Records with a song called “Sherry.” Scorcese said when he read the book, he said, “Frankie, listen, this book is like a cross between The Sopranos and Mad Men.” Because that’s the way it was back in the day.

Scorcese said when he read my book, he said, ‘Listen, this book is like a cross between The Sopranos and Mad Men.’ Because that’s the way it was back in the day.”

Did you see The Irishman, Scorsese’s movie?

Forget it. Completely fabricated. Listen, Frank Sheeran. The only thing he ever killed was a jug of bad wine.

Go back to your parents for a second. How old were they when they passed away?

My mom and dad, they were divorced even before — because one of the things that the Italian side said to my mother: “You got to divorce him.” And I only saw my dad on weekends. And it’s interesting, because when I became, by the grace of God, successful, I had him working for me.

Really?

He would collect the money at the door. I wouldn’t always get a fair count, but he collected the money at the door. And my mother would say, “You’re robbing from your son.” And he said, “Look, if it wasn’t for me, he wouldn’t be here.”

You got your start in show business on American Bandstand, right?

Well, what happened is, the Capuanos were in the ice business and the coal business, which, by the way, my father financed for them until they had a falling-out. So they had a television. My uncle, Jimmy Capuano, had a group, and they appeared on Bandstand in 1953. And it was mandatory — I had like seven aunts, uncles — mandatory to watch Bandstand and see your uncle perform.

I was out playing with the guys in the streets. So we went in, and I see this show where these kids are dancing. And I said, “Wait a second. Hey, Mom, I could dance better than that.” My Aunt Mim, who was Irish, who was married to my Uncle Jimmy, looked at me and smiled as if to say, Yeah, you can, and I did. Three days later, we’re on a corner. [My friend] Joe was one of the dancers, and they had a dance contest going on. And I said, “Joe, we’re going to sneak in.” We went to 46th and Market. There’s a line, but around the back is where the crew guys would go. The camera guys. We snuck in. Bandstand went on at 3:30, and we’re there about four, and the contest is going on. I jump into the dance contest with Joe, win the contest. Now I go back to South Philly. I’m a little star at the age of 13. People in the neighborhood say, “Hey, we saw you dancing on Bandstand.” I was hooked.

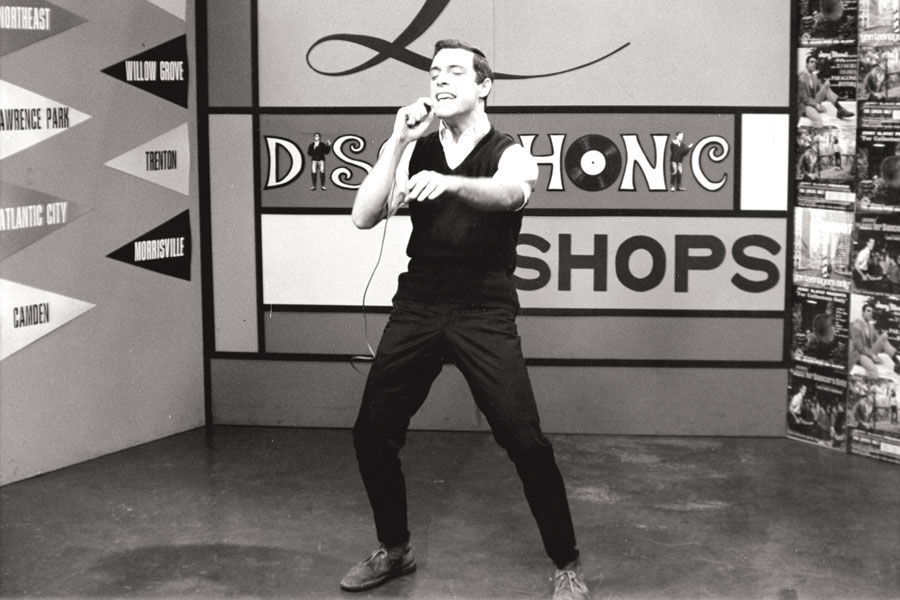

The Geator performing on his Discophonic Scene TV show in the 1960s. Photograph courtesy of Jerry Blavat

It seems like the music that you listen to when you’re a teenager or in your early 20s is the music you like for life. It just sticks with you for a long, long time.

You identify with that music. I’ll give you an example. When I did the radio show and I did the dances, a guy would dance with a girl. He called me up for requests: “Play a song for Sue.” I would play “I Only Have Eyes for You” by the Flamingos. She’d call and say, “Get a song for Tom.” I play “You’re Mine” by the Fireflies. Or “We Belong Together” by Robert and Johnny. That music will always be, because it spoke for what a kid was thinking.

We didn’t know how to express ourselves back then, and the music did it. The Saturday Evening Post did a big article on me, and they called me the Pied Piper of Philadelphia because I not only played the music; I looked like one of the kids. I danced with the kids. I was a part of this wonderful city, and I always believed if God gives you a gift, give it back.

It’s a little like what social media is today for teenagers — a way to connect.

Absolutely. It was, but radio has changed. Back then, I was able to talk before I played the music. If there was a problem at a school, a priest would call me: We have a problem here. I would go down and I would talk. I became not only the music, but a spokesman. Today, there’s no more radio. They push buttons, and there is no camaraderie between the audience and the radio. Radio for a kid growing up was the most important part of his life.

Even as we’re talking, you’re snapping your fingers. Where does that come from?

When I first was on the radio, they would criticize: Oh, he’s talking over the record. No, I talked over the intro. Sixteen beats. Disc jockeys have to use a clock for them to talk. In other words, they’d have a clock to say, you have 10 seconds before the lyric. Me … [snaps his fingers in time]

You’re counting.

I count. It’s a rhythm beat inside this body.

Let’s talk more about the music. You’re very dedicated to a couple particular areas of music, right? Doo-wop. R&B.

Well, it’s anything that tells a story that you can dance to. That has a rhythm beat and that is not beefing on society or knocking this. It’s gotta be pure. It’s gotta be good. Listen, I play today’s music. I mean, I play Beyoncé. I play Lady Gaga. If it’s danceable. And that’s the wonderful thing about music. If it’s good, it doesn’t matter what year. I’ll give you an example. We own Memories in Margate for 48 years. From four o’clock in the afternoon, when you have a happy hour, to about nine o’clock, the average age is 65 to 90. From 10:30 on, the average age is 22 to 65. It’s the music. It’s the blend.

When you go back to those old records that you first heard when you were a teenager, do you still hear them the same way?

Every time I play a song, another thought comes into my mind: where I was, who was the girl that I was dating, and the broken heart when she dated somebody else. Music speaks for the human experience.

You do a show featuring Sinatra’s music. Were you and Sinatra friends?

We became friends. My mother would cook for Frank. My mother would cook for Sammy [Davis Jr.]. It was a wonderful family. Wonderful. I mean, when Frank would be at Resorts, Jilly [Rizzo, Sinatra’s friend] would call me: “The old man wants you to come over tonight. Hurry up, tell your mother to make the pizza bread.” So we would send macaronis over to him, and this was my world.

There was a report in the early ’90s that said you had mob ties. I know you denied most of it, but who were those guys in your life?

We talked about the neighborhood. Yeah. I grew up with Angelo’s family.

Angelo Bruno, the mob boss.

I grew up with all of these people. My mother came from the same town as Sue Bruno [Angelo’s wife] came from. I knew Angelo. I knew all of these guys, never saw them do anything wrong, okay? When Pattie, my wife, and I split, I had a 22-room estate. I had a swimming pool. I would take Angelo’s grandkids, and they would swim in my pool. At the end on a Sunday, I would drop them off at Snyder Avenue. Sue Bruno found out that I wasn’t living at home. I was living at the Drake. She said, “Where are you going to eat at?” I said, I’m okay. She said, “Come on, you’ll eat.” And I became closer to that family than I ever was. I would drive Angelo when he wanted to go see his grandkids up in Radnor, in Villanova. Very, very close.

When he died … they said, listen, you’re almost like a family member here. We don’t want this funeral to be like a circus. You know the newspaper guys. You know the guys who have been following Angelo. Would you be at the door and make sure only the mourners are coming in? Then I said to myself, “This guy was loyal. He was a wonderful man. His family took me in.” I knew that if I make this decision, that I will be hounded. I made a decision: Don’t worry about it. Sure enough, the press: How come Jerry Blavat is so close to Angelo Bruno, to Phil Testa? I knew all these guys. What happened is, after that, they came after me with all kinds of investigations.

You say you didn’t see those guys do anything wrong, but I’m sure at some level, you knew what they were doing.

If I walk with a priest, does that mean I’m a holy man? If I’m walking with a banker, does that mean I’m a banker? You are what you are. As long as you don’t do anything wrong in front of me to jeopardize our friendship. Bam. That’s the rule. Never jeopardize friendships that you have.

That sounds like a South Philly code.

Absolutely. That’s even today.

In recent years, you’ve been throwing these extravaganzas at the Kimmel Center. How did those get started?

When they were putting the Kimmel Center together, Ed Rendell was the mayor at that time. Sidney [Kimmel] put up all the seed money for [the building], and we were having dinner. Sidney says to me: “Why don’t you do one of your rock-and-roll shows?” ’Cause I was doing rock-and-roll shows at the Robin Hood Dell when Jim Tate was mayor — big shows, 40,000 people back then. Sidney said, “We don’t only want [the Kimmel Center] for the Orchestra; it should be for everybody.” The first year, three shows. The next year, four shows. This show we did [in January] was 41 shows. It’s that many. It’s a tribute to the music and the loyalty that tri-state Philly, Jersey, Delaware have to this music.

When I get up in the morning, I got to get to the gym right away. ’Cause I feel like I’m 30 or 40 — but the body says no, Geat, you got aches and pains, you got a torn disk.”

How are you feeling about turning 80?

Youth is a gift of nature. Age is a work of art.

What’s the difference between the Geator at 80 and the Geator at 40? Are you wiser about things?

My mind has the same excitement. When I make people happy, when I do what I want to do and I have the freedom. Now, I realize, though, at the age of 80, the body is not what it was at 40, so when I get up in the morning, I got to get to the gym right away. ’Cause I feel like I’m 30 or 40 — but the body says no, Geat, you got aches and pains, you got a torn disk. But I’m going to make it on by.

So you can just keep doing your thing forever?

If God keeps me healthy, and as long as I see people smiling and laughing and dancing and comin’ to see me, I’ll do it. When I can’t do it anymore, I’ll just fade away a little bit over the mountain, across the sea. That’s where I’ll be if you want to be with me.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.