Krasner: “We’d Like to Get to the Truth” About Cop at Center of Meek Mill Case

In a new interview, Philly’s DA says that his office hasn’t “rendered a judgment” on whether retired narcotics officer Reggie Graham is actually guilty of corruption allegations that were cited in Mill’s bid for a new trial.

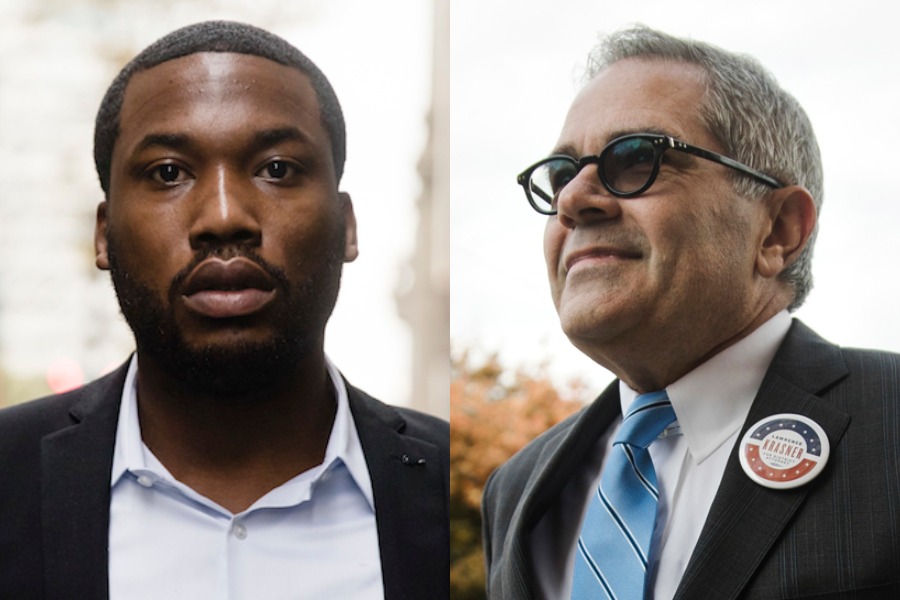

Left: Meek Mill (Matt Rourke/AP). Right: DA Larry Krasner.

The Year of Meek Mill was packed with drama, featuring a rapper wronged by the criminal justice system and a gripping tale of dirty cops faking evidence, beating suspects, and lying on the witness stand. But the cop at the center of the drama, Reginald Graham — a retired narcotics officer accused of corruption — might yet emerge with his reputation intact.

“I never lied, I never stole, and I never said I did,” said Graham last June, in his only interview on the subject thus far. That interview sparked an investigation and the uncovering of multiple documents suggesting Graham was the furthest thing from a corrupt cop: He was, instead, a whistleblower.

Today, even Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner declares himself unconvinced that Graham was a bad guy. “We’ve never charged Reggie Graham with a criminal act,” says Krasner, in a new interview with Philadelphia magazine, “and we never rendered a judgment that he was unquestionably unethical.”

The situation surrounding Graham, says Krasner, is murky, and “we’d like to get to the truth.”

The DA’s words add yet another twist to a story loaded with fateful turns. In November 2017, Mill was sentenced to jail by Judge Genece E. Brinkley for technical violations of his probation, sparking a massive public outcry for justice reform. Come April 2018, however, he was free on bail after private investigators working on his behalf uncovered damaging information about Graham, the lead officer who arrested Mill on gun- and drug-related charges.

Krasner’s predecessor in the DA’s office, they discovered, had placed Graham on a list of witnesses who could not be called to testify without the permission of a supervisor — his credibility undermined by earlier accusations, in 2013, of theft and lying to federal investigators. Though Graham was never charged with a crime, the Philadelphia Police Department of Internal Affairs hit him with disciplinary charges of theft and conduct unbecoming an officer, and a police board found him guilty. Graham had even supposedly admitted he’d lied, making it easy for heavyweight media outlets like Rolling Stone and Dateline NBC to depict him in villainous terms. Still-new DA Larry Krasner had even seemed to sign off on Graham’s guilt, supporting Meek Mill’s bid for a new trial — and it is this appearance against which Krasner is offering some pushback now.

“Our position was that Mill deserved a new trial based on the information about Graham,” says Krasner. “As a legal issue, this information should have been passed on to the defense by the prior administration, but … it was not a judgment of Graham.”

As victories go, this one is highly qualified. Krasner is not exonerating the ex-cop at this point. But it is another big step toward understanding the cop’s story — and the role he might actually play in the narrative of the Philadelphia police narcotics department, which public defender Brad Bridge describes, artfully and accurately, as offering up some “new scandal every five years … so regularly you can set your watch by them.”

The chief reason for this slow shift in Graham’s fortunes is that the paperwork appears to back him up. Law enforcement documents, including interview notes discovered from FBI and Internal Affairs investigations, reveal that Graham never did admit to lying or stealing. In fact, he’d acted as a whistleblower, even a would-be hero, who provided information to various members of law enforcement about corruption in his squad and faced retribution as a result.

That version of events is further bolstered by retired federal prosecutor Curtis Douglas, who said Graham had told him of corruption in his squad all the way back in 2003; and by Mill’s judge, Brinkley, who wrote last summer in a legal opinion denying the rapper’s bid for a new trial that the evidence points to Graham’s “truthfulness in dealing with a difficult atmosphere of corruption in his immediate work environment.”

In that June filing, Brinkley also went after the DA’s office — hard. The DA’s office agreed with Mill’s attorneys that the rapper deserved a new trial, she concluded, without conducting any investigation of the allegations against Graham. She even quoted her own exchange with assistant district attorney Liam Riley, who admitted to her that the commonwealth hadn’t reached out to any sources who might credibly speak to Graham’s guilt or innocence. These omissions included Douglas, the federal prosecutor, and police officer Alphonso Jett, who’d given a statement to federal investigators that exonerated Graham of the chief allegation of theft he faced. For a new DA whose entire career and political platform rested on the belief that his predecessors and the police require reform, his sudden willingness to accept the findings of these offices without further scrutiny appears particularly off-brand.

Today, Krasner declines to talk about “any investigation we might have done” since, but it isn’t hard to find a key political supporter of his who also believes in Graham. Rochelle Bilal is president of the Guardian Civic League, which represents 2,000 police officers and endorsed Krasner last June in his run for district attorney. Bilal says she spoke to Krasner directly about Graham. “When a cop has gone bad,” she told me in an interview this summer, “other police hear about them for years before anything happens to them, before they get arrested or get in trouble,” she says. “And in my position, I hear these things. But I had never heard a bad word about Reggie Graham, so these accusations about him never really made any sense to me.”

Krasner acknowledges that the Philadelphia Police Department sometimes punishes whistleblowers. That history, in fact, runs deep: Norman A. Carter Jr., Philadelphia police sergeant Tyrone Cook, and, pointedly, Guardian Civic League members in the narcotics department have all come forward with stories of retaliation for their attempts to address corruption in the department.

Now it appears to be Graham’s turn — and his accusers do boast dubious records. Police officer Jerold Gibson, who offered an affidavit contradicting Graham’s account of Mill’s arrest, was himself arrested, jailed and dismissed from the force over a theft charge. And Jeffrey Walker, Graham’s central accuser, who claimed Graham engaged in theft, has admitted to engaging in systemic and long-term corruption in the narcotics department. In fact, it was Walker himself, among other cops, that Graham had been blowing the whistle about years earlier. And so Krasner appears wise to adopt this careful public stance.

“I think it is obvious that there are people in the past who’ve said, ‘Hey, look at these guys, they’re corrupt’ to set up a means of defending himself later in case the shit ever hit the fan,” he says. But he also allows that the affidavits filed about Graham by Gibson and Walker are “of uncertain truthfulness.”

Where this leaves us is still fixed in story’s middle and not its end.

Mill remains free on bail while his attempts to win a new trial wind through the courts. He appears to have warmed to his role as a spokesman for criminal justice reform quite nicely, turning up every month or so with a new single or statement designed to get America woke. But the fact is, if his bid for a new trial fails, he could yet be sent back to prison.

Graham, on the other hand, has been hit with two federal suits in the wake of his public downfall, both curiously absent of detail. “I had a hard time,” says Carlton Johnson, the attorney defending Graham against the suits, “discerning what, if anything, my client is accused of doing.”

The suits look, to Johnson, like a “transparent money grab,” designed to eke some settlement out of the city. The result is that Graham, though beaten up for months in the media, appears to be notching some small but meaningful wins. And as the months pass, he looms as a potentially big figure in the Philadelphia police department — a whistleblower who might yet get brought into court to tell his story. And if that ever happens, Larry Krasner would like to hear him out. “We’d love to talk,” says Krasner, “… if he or his attorney ever wants to get in touch.”

On its face, that sounds good. But there are people they could contact on their own, including a former narcotics supervisor who worked with Graham and Walker.

“There were just none of the red flags with Reggie that there were with Walker” and other corrupt cops, the former supervisor says.

Corrupt narcotics cops brought far more cases and at a hyper-fast pace, suggesting to this supervisor, who requested anonymity because interviews must be cleared with the department, that they were “just making stuff up … because that doesn’t take any time.”

Graham, by contrast, brought fewer cases because he was methodical and actually taking the time to gather real information “on real cases.”

Further, corrupt cops often use the same confidential informants to an extreme degree, but Graham’s roster of informants didn’t appear, Zelig-like, in case after case. And finally, he never faced a high volume of civilian complaints. “I do take a high number of complaints as a red flag,” says this former supervisor.

There’s more, too, but it all points in the same direction: “When his name emerged,” says the supervisor, “everyone who worked with him was just stunned because these kinds of allegations don’t come out of the blue. But we had never heard a bad word when it came to Reggie.”