What Would You Do If You Found a Bag of Human Ashes?

Photograph by Liz Spikol

*The names of this person and those related to him as well as identifying details of his death have been changed.

The day I found Charles started out pretty much like any other — well, except that I was doing a park cleanup and I never do park cleanups. It’s not that I don’t care about parks. I do. But I don’t have the social acumen for group activities that compel small talk, especially when that small talk might be about recycling. At the last park cleanup I attended, for example, I worked mostly alone, and came across a dead rabbit.

It was perfectly preserved. Lying on its side, eyes open, ears erect, it almost appeared to be mid-stride. Its fur was damp from the dew that day, its fluffy body marred only by a small red aperture where a BB pellet might have entered. Its body was entirely surrounded by fall leaves — the colors were sumptuous. I sat with it for a while, feeling sad and regretful and overwhelmingly sorry for a whole mess of things that had nothing to do with this tiny rabbit’s existence. When one of the other cleanup attendees asked what I was doing, I yelled back, “I found a dead bunny!” She seemed to think it was strange that this would delay me, and I was reminded again of how different I am from other people, the normal folks who go to a cleanup and pick up trash without crashing into existential crises. I felt tragic for the rest of the day, but made small talk, and more small talk, while the vision of that rabbit stayed in my mind like a lingering camera flash.

But do I love parks? You bet I love parks. So I did another cleanup for LOVE Your Park Week, and that’s how I found Charles.

The LOVE Your Park Week cleanup started in a wooded area next to the parking lot at the trailhead for the Wissahickon bike path. It’s adjacent to the Wissahickon Transportation Center on Ridge Avenue, which has 11 different bus routes coming through — a busy place. There are always lots of people around, waiting for SEPTA or walking gingerly across the Ridge Avenue Bridge so they don’t collide with bicyclists.

Yet the green space at this spot — where the Wissahickon empties into the Schuylkill — is stunning; there’s an old stone bridge that spans the banks of the river there and, beneath it, a dam that creates a waterfall. It’s the ultimate representation of one of Philadelphia’s greatest strengths: the way natural beauty is found in the middle of urban chaos.

Unfortunately, the woods and riverbank there seem to be considered by some residents a suitable place to throw trash. I guess if you’re waiting for the bus or standing in the parking lot and no longer feel like carrying that single-use plastic bottle of water (which, unlike Philadelphia’s high-quality EPA-regulated tap water, might contain E. coli), it doesn’t seem out of order to just pitch that bottle — or beer can or potato-chip bag or ballpoint pen or plastic bag or banana peel — into the woods. It’s a bad decision, but we all make them, and one day a group of dedicated small-talking strangers will come along and pick up your trash for you, erasing your sins.

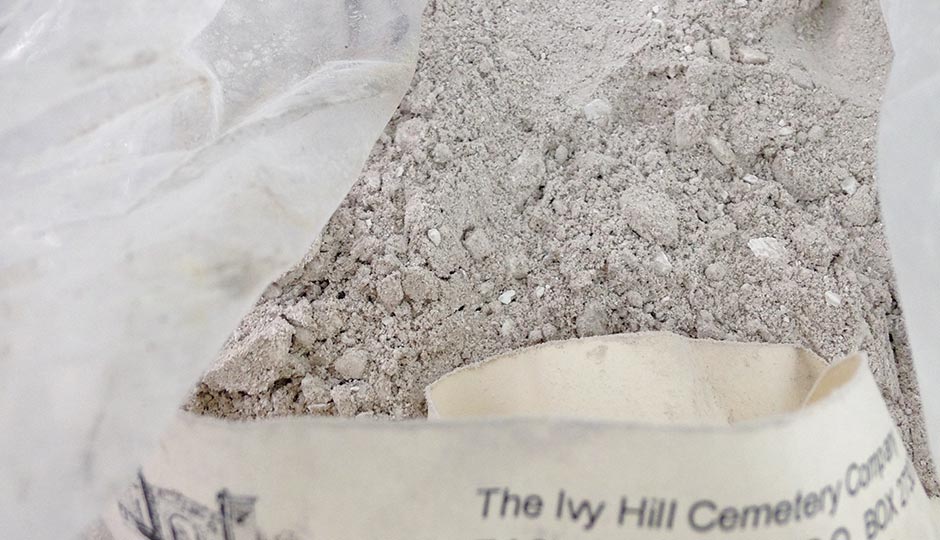

This time the army of strangers was outfitted with trash bags in one hand and trash pickers in the other. I was walking just inside the wooden fence next to the parking lot, keeping to myself, when I saw a clear plastic bag of white powder, about the size of a gallon milk jug. Cocaine? How exciting! Of course, I knew no real Philadelphian would stash such bounty here — or anywhere, for that matter, other than up his nose — so it had to be something else. The bag was dirty, with a couple bugs crawling inside of it, and the grain of the powder — extremely fine but with chalky chunks — looked familiar. Suddenly, I had two visions: an Oriental Shorthair cat with a triangular face that resembled a praying mantis more than a feline and whose meows sounded like a human infant, and a shy tan Chihuahua with a black button nose who always kept her tail between her legs unless she smelled steak or saw her owner unexpectedly. Both of these animals were long dead, but their ashes were in my apartment, in separate cedar boxes, because I’m the kind of person who keeps the remains of her pets. Not only that; I know the consistency of those ashes because I wept over the teensy baggies when they were handed to me by the vet. My next thought, then, was this: Wow. This must’ve been one hell of a big dog.

I took the bag into the parking lot for a closer look, reviewing the American Kennel Club registry in my head as I did: Great Dane? Mastiff? St. Bernard? I once worked at a newspaper where the publisher brought his Bernese mountain dog into the office of the paper’s very stuffy British owner, and the dog — a puppy, but already as large as a Smart Car — peed all over the carpet. Maybe this was one of those dogs? Then I saw there was a piece of paper in the bag. It had a picture of a building and a printed name and then something else I couldn’t quite make out. Black type on white paper. The bag was fastened with a twist tie. Naturally, I opened it.

I took the powder-covered paper out and shook it off. It was from the Ivy Hill Cemetery Company on Easton Road, not far from my house. It read:

CREMATED REMAINS OF

CHARLES CHESTER SMITH

DATE OF DEATH: 5/8/2009

CREMATED ON: 5/22/2009

AGE: 54 Yrs.

Suddenly my fingertips, covered in white powder, felt hot. This was no dog. It was a human being. I dropped the card back into the bag and wiped my hands on my jeans, leaving white streaks. My heart was pounding. What should I do? I looked around at the group of strangers with their bags and trash pickers, all bent over, working silently, like an urban spin on The Gleaners. I thought about telling one of them, but this wasn’t like finding a dead bunny. And it definitely wasn’t small talk.

There was no way I was leaving the ashes there. Later, someone suggested that I had disturbed the intended resting place of this bag of remains, but that wasn’t so. This wasn’t the kind of spot where one goes to scatter ashes — or even to plunk down a nine-pound bag of them. It was the kind of place where people dump unwanted things. And at any rate, while it’s permissible in some cases to scatter ashes on city land (more on that later), it’s not permissible to leave a plastic bag of them adjacent to the watershed — but that has more to do with the plastic than the incinerated flesh. In any case, they would have to be removed.

I put the bag of ashes in my car, on the floor behind the driver’s seat, until I could figure out what to do. Then I felt unsure. The bag looked so vulnerable back there, so unprotected. I guess it might have been unprotected for six years in the woods, but just sticking it in my car on top of an outdated newspaper and an old paper map seemed wrong. The ashes were so visible. I took the bag out and put it into a green trash bag as though I was putting a sheet over a dead body, and then I put it back into the car.

I looked around for my boyfriend, who’d organized the cleanup, to tell him about the ashes, but didn’t see him, so I went back to picking up trash: a hubcap here, a cigarette butt there, a glass bottle and a pocketknife. I slid down a hill and landed next to a dead sparrow. I stopped briefly but didn’t mourn it as I had the rabbit. What’s a dead bird after you find a man?

The mausoleum at Ivy Hill Cemetery. Photograph by Liz Spikol

IVY HILL CEMETERY, founded in 1867, is one of more than 200 cemeteries in Philadelphia, three of which are on the National Register of Historic Places. When history buffs come to Philadelphia, they often stop at our cemeteries. Seven signers of the Declaration of Independence are buried here, as are 40 Civil War-era generals. So are Ben Franklin, Betsy Ross, Commodore John Barry, General George Meade and countless other historical figures. There are cultural icons, too, like Thomas Eakins and John Barrymore.

There are also the unknown dead, buried in places like Weccacoe Playground, once an African-American burial ground, or in the city’s potter’s fields, where the unidentified dead were buried until the 1980s, when the Philadelphia Medical Examiner’s Office began the practice of cremating identified but unclaimed bodies. The office keeps the ashes for about 10 years, to provide time for relatives to turn up. In 2010, 1,500 unclaimed remains were buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery with a tombstone that read: 1,500 CITIZENS CONSIGNED TO EARTH/CITY OF PHILADELPHIA 2010.

At Ivy Hill, along with the graves of Joe Frazier, Harold Melvin, Marion Williams, two Civil War generals, and several other notable people in sports, music, and political and military history, there is a grave for one of these unclaimed citizens: the child known as the Boy in the Box. In 1957 his naked body was found in a cardboard carton in a thicket near Susquehanna and Verree roads. The box was from the J.C. Penney at 69th and Chestnut and originally held a white bassinet. The kindergarten-aged boy weighed 30 pounds and had blue eyes and light brown hair. He had bruises all over his body and was covered in a cotton blanket. Who was he? How had he come to such a sad end? Despite decades of work by multiple detectives and an investigation by the superb minds at the Vidocq Society, the boy’s identity remains a mystery. But after many years in a potter’s field, his remains were moved to a more dignified resting place: an elevated plot with a stone bench and a large marker that says AMERICA’S UNKNOWN CHILD at Ivy Hill’s entrance.

When I found out the Boy in the Box was buried at Ivy Hill, it seemed like a sign. I wrote about him years ago and was friends with one of the men who worked on the case, the late forensic sculptor Frank Bender. And wasn’t it some kind of kismet that Ivy Hill was so close to my house? Perhaps I’d found Charles for a reason. The best omen of all was the way Joe Frazier’s image on gray marble was hit by sun and clouds the first time I went to Ivy Hill, making him look like a heavyweight hologram. Help me, Obi-Wan Joe. You’re my only hope.

The office at Ivy Hill was plain and workmanlike. There was nothing to suggest that the women who worked there were dealing with the business of death; they could as easily have been doing taxes. While I stood by her side, a woman looked up Charles’s cremation identification number on the computer and located the funeral home where he’d had his service. I didn’t know why I was standing there while she did this, but I was happy to keep her company. Then she gave me the name of the funeral home and the phone number and told me to give them a call to locate next of kin. I was confused. Charles was in the car. Behind the driver’s seat. Didn’t they want him? No, they did not. If the funeral home was uncooperative, they said, then I could bring him back.

Later that day, I called the funeral home. At this point, I had Googled Charles, of course, but there were few results. There was no obituary in local papers. I learned only that he was born on Sunday, June 27, 1954, the day the world’s first nuclear power plant opened not far from Moscow.

The woman at the funeral home found the records immediately. She said his wife was the contact person they had listed, and she told me her name: Sheila Smith. Terrific. She also said the number for Sheila had been disconnected. She volunteered to walk to Sheila’s house, which was only a few blocks away, and knock on the door. She said she’d call me back with an update.

That call never came. When I emailed later, she wrote back simply: “I have not been successful in finding the next of kin.”

Had she gone to Sheila’s house or not? I did a search for Sheila’s name along with addresses near the funeral home’s location — and there she was. Well, if they weren’t going to pound on the door, I would. Charles needed resolution! I wanted to give these ashes to someone who’d known him. It didn’t have to be someone who’d loved him. Maybe he wasn’t lovable. But I felt it should be someone who remembered the timbre of his voice.

The four-story red brick apartment building, with vacant lots on either side, was boarded up, its windows broken or covered by graffitied plywood. What was once an ornate entryway with an awning was now a bare metal skeleton with a little bag of trash hanging from its curlicued metalwork. The door was padlocked. Later I learned there’d been a terrible fire at that building in 2011, two years after Charles’s death, displacing its roughly 30 residents. The damaged mess of a building is now for sale for half a million dollars.

The Ridge Avenue Bridge near where Charles’s ashes were found. Photograph by Bradley Maule

CREMATION IS INCREASING in popularity. According to the Cremation Association of North America, in 1998, 24 percent of dead people in the U.S. were cremated. In 2014, that percentage jumped to 46.7. Pennsylvania sits just below the national average at 42.9 percent. One reason for the increase is that cremation is more cost-effective than burial. A direct cremation in the Philadelphia area — no service, and you take the ashes home with you — generally starts at around $1,000. Like furniture delivery, this varies depending upon where the person is coming from and going to. But even taking extra fees into account, burials are much more costly. There’s the casket and the plot and the headstone and the mortuary services and perpetual grave care. In 2012, according to the National Funeral Directors Association, the median cost of a burial with casket and vault (sans plot) was about $8,000.

Other factors play into the popularity, though. Barbara Kemmis, executive director of the Cremation Association of North America, notes that cremation is more conducive to 21st-century realities, like the fact that family members often live at a distance from each other. “Cremation allows people to follow a different time frame,” she says, so that families can gather six months after the death to scatter the ashes. Cremation also allows for much more, shall we say, customization: Cremated remains can be shot into space, fashioned into jewelry, turned into vinyl records, or tattooed onto a loved one’s body. “If you dream of something you want to do with cremated remains,” Kemmis says, “you can find someone to help you do that.”

In November 2005, Tempe, Arizona, bar owner Christopher Noteboom came to Philadelphia for an Eagles game. The Doylestown native had lost his mother to emphysema in January, and she’d been cremated. She’d also been a very big Eagles fan, so Noteboom honored her in bold fashion: by running out onto the field in the middle of a game to scatter her cremains. He got as far as the 30-yard line, “leaving a cloud of fine powder behind,” according to AP reports at the time, before being escorted away by security and then arrested. Later, he told the TV news, “I know that the last handful of ashes I had are laying on the field, and will never be taken away. She’ll always be part of Lincoln Financial Field and of the Eagles.” Similarly, country music star Tim McGraw, Tug McGraw’s son, surreptitiously deposited a handful of Tug on the Citizens Bank Park pitcher’s mound before Game 3 of the 2008 World Series, to honor his dad. He was not arrested, however.

In Pennsylvania, ashes can be buried belowground and marked with a plaque or headstone; buried aboveground in a columbarium; scattered on private ground with permission of the landowner; or scattered on certain public grounds with approval or a permit. According to federal law, ashes can be scattered at sea as long as you’re three nautical miles from land, the water is at least 600 feet deep, and you report the scattering in writing within 30 days to the EPA. It is also legal, by the way, to throw a dead body in the ocean, as long as you report it to the EPA using the same Burial at Sea form — though the questions for non-cremated remains are a little different, i.e., “Did the remains appear to rapidly sink to the ocean floor?” I find it fascinating that I need an advance permit to park a moving truck in front of my building but I can take a dead body out to the ocean without doing a jot of paperwork beforehand.

Had I known this, perhaps I would have dumped my grandmother in the ocean, since she spent some of her best times at the Jersey Shore as a young single gal (but not as a virgin, she’d remind me, lest I make the mistake of saving myself till marriage). Instead, we did a bargain-basement cremation for her. The place my father found was so cheap, in fact, that he asked why. The guy replied: “Don’t ask why we’re so cheap — ask the other guys why they’re so expensive!” My dad thought that was pretty good logic.

IT WAS A MAN’s VOICE on the recording: “This is Rob and Jen. Leave a message.” I spoke quickly. “Hi, I’m looking for a Jennifer Smith who may have been related to Charles Chester Smith who died in 2009. I, um, I have … I was doing a park cleanup and I found a bag of ashes, Charles’s ashes, and I’m sorry to bother you but I’m trying to reach someone who’s part of his family.”

I had already reached out to Jennifer on Facebook, though she wasn’t active there anymore, and sent messages to a number of her Facebook friends with similarly awkward wording about dead people and cremains. When she called me back, she wasn’t happy.

“How did you get my number? This is a private number.”

“Well, I’m a journalist, and I used a database. … ”

“I haven’t been married to Charles in 16 years,” Jennifer said. “He was married to someone else.”

“I am so sorry to bother you and intrude on your privacy. It’s just that I have his ashes, you know, and I’d really like a family member to have them … if they want them.”

There was a pause.

“Where did you say you found them?”

I told Jennifer the whole story. She was amazed. She’d been married to Charles for 20 years. “But we all live in West Philly. I have no idea how in God’s green earth they ended up there.”

Jennifer said nothing specific about her marriage to Charles, and I felt rude asking. After all, who knows what happened between them? They were divorced — maybe this was a terrible reminder of a life she’d rather forget. She did say, though, that her son — along with Charles’s oldest daughter — made all the arrangements for the cremation. The ashes were supposedly divided between his second wife Sheila and someone else, and then, as far as Jennifer knew, Sheila and her daughter moved out of town. As for Charles’s other kids, his two sons were now incarcerated. I told her Ivy Hill could take the ashes back, but she said she wanted some time to resolve this among the family. Later that day, unable to contain my curiosity, I drove past the house that Jennifer and Charles lived in when they were married. There were red and pink heart stickers all over the mailbox.

HERE’S WHAT ELSE my journalistic database told me about Charles:

He spent most of the ’90s and 2000s living in West Philly, close to the El.

He filed for bankruptcy four times.

He was sued by a couple of very sketchy-sounding mortgage companies in the ’90s, one of which was successfully sued for violating the Truth in Lending Act.

He was sued twice by individuals for outstanding debt.

A small-claims suit for just over $2,000 was filed by Slomin’s Inc. against someone with his name shortly after his death. The Haverford Avenue residence that’s listed on that filing is now a church.

I have addresses, financial records and little more. This is not enough. How could it be? My curiosity about people — what my childhood Fairmount neighbors called my “noosey-ness” — is not, as some have mistakenly thought, the journalist in me. It’s a hunger for narrative. I am keen on details that will reveal the larger structure of a person’s life, especially if that person is a stranger. But unlike a woman on the train, about whom I can invent a story, the ashes of a man leave me little to go on. I feel that if I knew what he looked like, some mystery would be solved. So I ride through his former neighborhood, down tiny streets and dead ends. But the drive is crushingly depressing. I sometimes forget how bombed-out and wretched Philadelphia can be. Was it like this when he lived here? I just don’t have enough information.

I have found a Sheila Smith who could be the one. She’s on Facebook and the right age. Her profile dovetails with what Jennifer said. We have mutual friends, which suggests a Philly connection. I send her a note and wait. And wait. I realize it’s entirely possible she doesn’t want to hear from me, but they were married when he died. Finally, after a long 12 days, I get a message back: “I am sorry but I never live there before, my home is Ohio but I live [somewhere else] now.” Another door closed.

So I decide to throw in the towel and reach out to my friend who works in law enforcement — let’s call him Julio. He’s the lucky guy who gets my texts when strange things happen around me that I can’t explain. He doesn’t get easily ruffled. A typical exchange might go like this:

Me: “I just heard gunshots and screams and breaking glass. What do you think?”

Him: “I think you should move.”

I once asked him for help with a kitten stuck in a tree, and he suggested I tell the cops the kitten was armed because I’d be sure to get them to respond that way. When I make a rock album, it will be called Kitten’s Got a Gun.

I text Julio about the ashes. His first response: “Only you, Spikol.” My goal, to be honest, is to determine that Charles was a terrible person. Then I can accept that he ended up dumped next to a parking lot. I’m hoping for a lengthy criminal record, maybe some domestic abuse. A murder would be good. Over coffee, I ask Julio if he can put Charles’s name into a database, just see what he comes up with. He predicts that getting such information will take about 45 seconds. He also predicts this: “I’ll bet he had some kind of ’70s Afro.” I laugh and disagree: “I get a balding vibe,” I say. Then I sigh. Yet another indignity: The body of Charles Chester Smith has been turned into a macabre parlor game.

TODAY IS THE DAY I return the ashes. They’ve been under my sink for ages, nestled between the Endust and the Shout. Not very dignified, I know, but I put them there after realizing that my dog might get curious about the bag, with its smells of the Wissahickon, and do something inappropriate. Seemed like Charles had suffered enough without getting peed upon by a spoiled three-legged Chihuahua.

I’m supposed to meet Jennifer outside my office, on the corner of 19th and Market, for the handoff. It seems garish to hand her a trash bag with her ex-husband, so before we meet, I go to the store to find a gift bag. It’s ridiculous, I know, but it’s the only thing I can think of to make the situation better. Obviously, the ones that say CONGRATS or have colorful balloons on them are out of the question, so I go to the plain ones. But what color do I buy? Red makes me think of the Phillies, though I’m willing to admit not everyone would have that response. Blue seems too happy-skies. Yellow is sunny. The alternative? Black. Well, that’s appropriately funereal. But on my way home, I second-guess myself. Isn’t that overdoing it? Putting them in a black bag? Sadly, there is no etiquette guide for this situation.

Jennifer and I have simply said 19th and Market at 1 p.m. In front of my office building, for reasons that remain obscure to me, there are people playing tennis — net and all. There are tables with bank reps trying to get people to sign up. There are worker bees eating lunch and having cocktails. There are people waiting for the bus and emerging from the subway entrance. It’s crowded. How will I recognize Jennifer?

I stand on the corner holding the black bag, trying to look like a person holding human remains. I look at all the 60-plus women who walk by and wait for some kind of awareness. I’ve been living with Charles for a long time now and feel we are intimate. I’ve invented things about him: I think he was a large man, with a wide smile and a big, deep laugh. I think he had a mustache. I think we would get along. Because of this imagined intimacy, I believe I’ll know his ex-wife. One lady with short gray hair and a black-and-white silk shirt looks like she might be right, and she’s walking slowly, as though she might be looking for someone. I walk toward her, but someone cuts in front of me to hug her. “Barbara!” the other person says. Okay, not Jennifer. I resume my watch on the corner. In the next 10 minutes, the only other possibility is a woman who comes up from the subway and looks around confusedly. She’s wearing a denim cap, an American flag t-shirt and denim shorts, and something tells me that Jennifer wouldn’t wear that outfit. Still, she’s definitely looking for someone. I approach gingerly. “Jennifer?” She smiles with delight. “No!” she says.

It turns out Jennifer won’t be coming today; her daughter Shauna will drive up to the corner of 19th and Market instead. When I open the door to her SUV, Shauna is talking on the phone to a friend. “Hold on a minute,” she says to her friend. She gives me a huge smile. “Thank you so much,” she says. I plunk down the black bag on the passenger seat and blurt, “Is this your dad?” So much for being sensitive. “No,” she says. “My mother hasn’t been married to Charles for decades. She does have children by him, though. He had children.” She says they’re going to try to get those children to take the ashes. I want to ask if the arrangements are secure, but how is it my business? Her friend is still holding on the phone, and she’s parked illegally. I know I should let her go. But I have to ask: “How did he die?”

“Heart attack,” she says. “He was sick. He died young. He had diabetes.”

I let her get back to her phone call and the rest of her day. But as I walk back to my office, I feel so lonely. I know he wasn’t anyone to me, really, just a figment of my imagination. Yet I feel like I’ve lost someone. I’m also worried about where he’ll end up. The sons are in jail? For how long? Will the daughter want him? Or was it daughters? I’m still unclear on the kids thing, but I don’t need to untangle it anymore. It’s no longer my mystery. This fact makes me feel out of control and slightly panicked, as though I want to get him back. Maybe I should have scooped some of him out of the bag and saved it, I think. I am really glad I have this thought after Shauna is gone.

When I said goodbye to Shauna, I told her I was writing an article. She said, “That’s good. You can call me if you have any questions.” Of course, I have nothing but questions. Who was Charles? Was he a good person? Do his children look like him? What was his favorite food? Did he like dogs? Was he the kind of neighbor who helped people with their groceries? Most of all: What did Charles do that led to his being abandoned? Maybe what I really mean is this: Did he deserve it? Does anyone?

I’M ON THE TRAIN, traveling from Mount Airy to Center City, when I get the text from Julio: “I. Was. Right.” That’s followed by a photo of a man who looks distinctly 1970s, with a salt-and-pepper Afro. I don’t have to ask Julio who it is. I laugh at first. Yes, Julio was right about the Afro. My boyfriend looks over my shoulder. “It’s him,” I say, and suddenly I’m sobbing. “Hey, hey,” my boyfriend says, “what’s going on?” I don’t have an answer. I just can’t stop crying. The next text says, “Died 10 months after that photo was taken.” Julio won’t tell me where the photo came from, but he does say it’s not a mug shot, and that Charles didn’t have a criminal record. From all appearances, Julio says, Charles was a good person.

In the photo, Charles’s black-collared shirt is open at the throat, revealing a double chin. He has a beard and mustache. His eyes are distinctly wet, as though he’s been crying. His mouth is slightly crumpled. He looks undeniably sad. My whole body feels possessed by a desire to grab the man in this photo and tell him, “It’s okay, I’ve got you.” But it isn’t true, I don’t have him anymore, and I don’t even know if he went to the right place.

I look back at the photo and everything seems confusing and upside-down. For a moment, it’s as though photography is as magical as it seemed in the mid-19th century, when the daguerreotype was born and people saw themselves frozen for the first time. This tiny photo on my iPhone has turned back time, transforming a pile of white powder into flesh and blood. It has brought Charles back to the world of the living, just for a moment. Which is why I’m now struck — for the very first time, I’m ashamed to say — by the reality of the situation: Charles Chester Smith is gone — and I don’t just mean his ashes. Charles Chester Smith is dead.

Published as “What Would You Do If You Found a Bag of Human Ashes?” in the October 2015 issue of Philadelphia magazine.