Drexel’s Virtual Butt Draws National Attention — Again

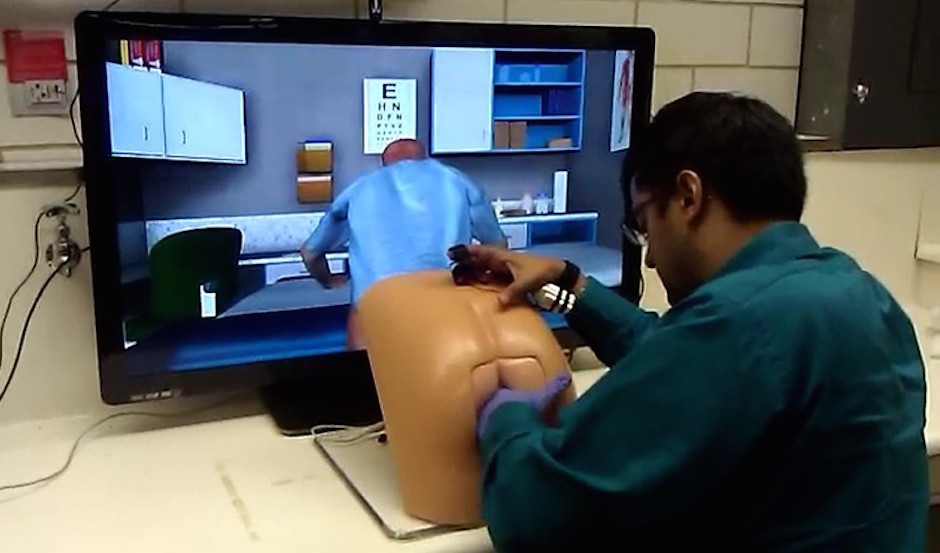

Photo courtesy Dr. Benjamin Lok

Last week, as I scrolled through my Facebook feed on my phone, I kept seeing the same photo of a seated man with his gloved hand inside a plastic dummy’s butt. It looked like a CPR class gone terribly wrong. I didn’t read the accompanying articles because, well, there were other things to do. But when I was told today that the dummy had been developed, in part, by a professor at Drexel, I got interested. A Philly connection? I had to learn more. My priorities are in order.

Turns out, the photograph is of a medical student giving a virtual patient a prostate exam. It’s part of a project called the Virtual Patients Group, which includes computer scientists, medical doctors, pharmacists, psychologists, and educators all doing research and development into improving interpersonal skills in healthcare environments. They provide tools for medical school curricula and public health exhibits—tools like Patrick, pictured in the photo, a virtual human who is half-onscreen and half-mannequin. The interpersonal interaction with Patrick (voiced and controlled by an instructor) includes taking his history. When it comes time for the physical exam, the actual mannequin—which has sensors inside—allows the student to perfect the hands-on technique. This combination of onscreen virtual patient and mannequin for hands-on application is also in use for breast exams, another intimate scenario in which medical students need practice with bedside manner and a gentle, precise touch.

Obviously, the photo has people laughing and making all manner of jokes and puns. But what’s interesting is that this isn’t news: Patrick was developed as the result of a grant from at least six years ago, and the first round of media coverage was in 2013—including a thorough article in the Inquirer and an interview with the lead researcher in The Mary Sue. So why now? It seems to have started with Christina Farr, editor of KQED Science, who published the photo and an accompanying story this week (she gave a hat tip to a 2013 Medical Daily piece). Then Mashable picked it up from KQED. Then UPI, a wire service, picked it up, reporting on it as though it were new news, and then Metro UK picked it up and so on. Christina Farr’s Twitter feed reports that the butt simulator piece was, as of May 26, the most read article on KQED.

The simulator’s lead designer, Benjamin Lok, has gotten used to seeing the story get resurrected every now and then. “I guess the picture itself hits a nerve,” he said today. “Usually the reactions are first laughter. Then for those who take a second to think a bit about what is going on, some people go, ‘Huh… yeah, I guess I never thought about how to practice one of those, and yeah, simulation makes sense. But then some go back to laughter again. I think the laughter is somewhat nervous laughter too, as if to think, ‘If I ever have to be trained to do a prostate exam, what exactly would I do and how would I feel?'”

For Dr. D. Scott Lind—chairman of the Department of Surgery at Drexel University College of Medicine and one of Lok’s partners in developing Patrick—that question of “how would I feel?” is the raison d’etre for continuing to perfect virtual-patient technology. “We’re very technologically adept at healthcare in Philadelphia,” he says, “but we want to make sure we remember the patient-centered and communication and empathy part of [medicine]. Even though you’re using a virtual patient, we’ve shown that you can elicit empathy and all the other elements that are essential to the interpersonal interaction with your healthcare provider.”

Lind and his colleagues have actually taken the virtual patient technology in a somewhat different direction, using the city as a laboratory for studying the way race and ethnicity can shape medical care. “Because of the multicultural environment that we practice medicine in here in Philadelphia, we did an offshoot study where we changed the skin tone color of the virtual patients.”

For example, they did a study recently where they had medical students give an exam to two patients: one whose head was covered with a headscarf, and the other whose head was not covered. The idea was to compare the treatment of Muslim and non-Muslim patients. “We found some significant differences, potentially implicit bias related,” Lind says. For instance, both the physical exam and the history taken were less detailed when the students interacted with the Muslim woman. They also didn’t detect a breast mass as well as they could have in the Muslim women. Such behavior, Lind says, is not unusual; it’s been borne out in the literature. With the examples of the virtual patients, Lind says, “we think we can study and enhance the students’ communication skills and physical exam skills to make them culturally competent.”

Relatedly, Lind and colleagues are working on creating a virtual Asian patient to determine if cultural competence is part of the reason Asian women have lower compliance with a host of screening guidelines. And they’re utilizing virtual patient technology in a study looking at why underserved minority patients don’t participate in clinical trials as frequently. “One of the reasons may be related to our inability to address all their cultural needs when we’re talking to them about trials that might be open,” says Lind. In conjunction with the School of Public Health, Lind and colleagues are working with a local group called Women of Faith and Hope, which helps cares for underserved African American women with breast cancer. The group is providing input to develop virtual patients for students interacting with those patients, hopefully enhancing participation in future trials. “We’d ultimately like to have more minority representation in the health professions,” says Lind, but at the very least, “you want to make sure that everyone is aware of the ethnic and diverse elements that are important in an interaction from a communications and physical exam standpoint.”

As for Patrick going viral again, Lind says, “I’m not sure whether it’s in part related to the intimate exam component of it—it’s also probably the interest in technology.”

That’s giving people a lot of credit, I think. But either way, Lok says, “I think getting people to think about science is always a good thing, so for that I’m happy it comes up again. That my career is likely to be associated with a prostate exam is I guess the price to pay.”