Philly’s Black Community Has Been Disproportionately Affected By COVID-19. Why Is the City Just Now Doing Something About It?

While black people have accounted for more than half of the coronavirus deaths in Philadelphia, the black community was left to rely on grassroots efforts to bring them testing while the city waited on federal funding.

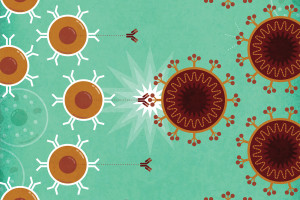

Dr. Ala Stanford, founder of the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium, administering a COVID-19 test in Philadelphia. / Marshall Mitchell

Protests are never about one thing. Instead, it’s years of simmering anger over numerous injustices that often lead people from disenfranchised communities to resort to marching and shouting, with signs raised above their heads in the public square. The protests and riots that occurred last week in Philadelphia and across the country were no exception. These demonstrations aimed rightfully at the disproportionate threat that police pose to black lives. That conversation has since expanded, forcing a collective examination of inequalities that affect black people in every aspect of their lives, from housing, jobs and business, to education and healthcare.

Health professionals have rightly called racism a public health crisis and the coronavirus pandemic has emerged as perhaps the most telling example of the impact disparities in healthcare can have. While more than 110,000 people in the United States have died from the COVID-19 roughly 20,000, or 18 percent, of them are black, though only 13 percent of Americans are black. In Philadelphia, black people accounted for half of the 23,951 positive cases of COVID-19 and more than half of the 1,433 people who have died from the virus as of June 10th, while the city’s black residents make up about 44 percent of the population.

This week, roughly 90 days after Philadelphia saw its first case of coronavirus, the city made its first significant attempt to address the disparate effect the virus has had on its black residents by awarding the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium (BDCC) a grant to provide coronavirus testing and contact tracing services. To date, the BDCC has tested more than 5,000 people from neighborhoods in and around Philadelphia without any financial support from the city. Ninety-six percent of people tested by the BDCC were black.

The grant is the result of a request for proposals that the city issued just two weeks ago, seeking qualified organizations to implement community testing programs. Securing the grant is a win for groups like the BDCC, who’ve been praised for being a critical resource for marginalized communities in Philly who struggled to find access to testing. It’s also a harsh reminder of just how slowly the city has responded to disproportionate deaths from the virus among its black residents — especially given that they only began reviewing the proposals after federal funding was secured.

City officials say they’ve been providing COVID-19 testing since March and that they’ve “supported healthcare systems, Federally Qualified Health Centers, and groups like the Black Doctors Consortium through donations of PPE and testing supplies, and technical support throughout the pandemic to increase the number of sites that could do testing.”

But Dr. Ala Stanford, the founder of the BDCC, says this “support” has been lacking. “I kept seeing stories that said the Mayor or the city had given us funding. That’s not true,” Stanford says. “At one event, someone brought three boxes of gloves and about 20 masks and said they were from the city. That’s it. I can tell you my neighbors have left more than that on my doorstep to support our effort.”

Meanwhile, many black residents say they faced barriers to accessing the city’s testing sites. To understand the disconnect between what the city touts as an adequate response and what residents say has been subpar, you first have to look at the underlying issues that all but assured black residents would be hit hardest by the virus.

Several narratives have emerged to explain why the black community has been so disproportionately affected by the pandemic. Some point to the fact that many people in the black community have pre-existing chronic conditions like diabetes, which, for example, affects 4.9 million black adults in America, making them more susceptible to worse outcomes when they contract a virus like COVID-19. Others note the number of people in the black community who lack health insurance, and recent data shows black people were second only to Hispanics among demographic groups with the highest uninsured rates. Still, others say that it’s the deeply rooted fear of being mistreated by healthcare institutions — and the stigma of not being heard when presenting to healthcare professionals — that, for decades, has kept black people from seeking out healthcare.

In Philadelphia, many of these historical challenges have converged, creating a system that has put more black residents at risk of contracting contracting the virus, and prevented them from getting tested for it.

“I do think there’s some bias that’s at play sometimes when black people don’t necessarily present in a certain way, they tend to be either dismissed, not listened to or turned away,” said Jefferson Health physician Pierre Chanoine. “I think fear probably plays into it too. I think a lot of things are involved. But on a very basic level, I think, early on, the criteria for getting a test was too stringent and there was simply a lack of testing being done.”

The city only recently loosened its guidelines for coronavirus testing, which originally reserved tests for older adults who had symptoms and for frontline healthcare employees. In the early months of the pandemic, many black people seeking testing were turned away. Two black hospital employees say they were denied COVID-19 tests in April because their employer chose to reserve tests for physicians only. The employees, who requested anonymity for fear of retribution from their employer, say they were told that as young patient care technicians, they did not meet the criteria for testing.

John Price, 72, the owner and operator of Price Funeral Home in West Philadelphia seemed to meet all criteria for COVID-19 testing. As a senior above the age of 50 and an essential worker who regularly comes in close contact with COVID-19 victims, Price sought a coronavirus test in early May. But when he arrived at the site, he was told he’d need a referral from his primary care physician in order to access the test.

“I don’t know if they consider us first responders, but we are first responders for these families. We deal with infected people on a daily basis, especially if we have to embalm, we’re exposed to blood-borne pathogens, the air in a person’s chest; if you’re not properly dressed, you will be exposed,” Price explained. “We’re seeing almost double the number of funerals we usually see. We’re trying to help these families plan and prepare; I don’t have time to get a referral.”

The complicated bureaucracy of healthcare created barriers for Price to protect himself, his family and his employees from the virus.

But like many instances in history when institutional structures have failed to protect marginalized people, community members themselves have stepped up to help their own.

In April, when coronavirus tests were scarce nationwide, and early data had only just begun to show how deeply the virus was affecting black communities, Ala Stanford launched the BDCC as the city’s first mobile testing site using her own funds and donations from a GoFundMe campaign. Stanford, a pediatric surgeon and founder of the private healthcare service, R.E.A.L. Concierge Medicine, established the group with a mission to reduce the incidence of disease and death from coronavirus in the black community by educating, advocating and offering free walk-up testing for COVID-19.

“When health-care workers were dying at rates near 53 percent in New York, we saw the government make special investments there,” Stanford said. “But here, the city was focused on every other group that they said mattered except for black people.”

Stanford’s group effort tackled several issues at once. Walk-up testing provided a new option for people without cars who were previously limited to the city’s drive-thru only testing sites. Tests were provided free of charge, removing the burden of cost for people who were uninsured or underinsured. And, according to Chanoine, who is also a BDCC volunteer, BDCC testing events were hosted by people from the community and in places community members could trust.

“The idea was, if we could set up in community centers and churches, people would be seeing folks that they already know and trust instead of strangers coming in. I think that has worked really well because there’s always a sense of mistrust and concern about the agenda. We had no agenda other than testing people,” Chanoine said.

“We have to keep in mind what this country has done to the black population and how they’ve been used as medical guinea pigs and really have not been treated with the grace and dignity that they deserve as human beings,” said recent graduate of the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine and BDCC volunteer, Natalie Gonzalez. “So, we understand that, rightfully so, they’re going to be feeling sketchy about it [being tested]. But I think because we all come from that same mindset of understanding where they’re coming from, it’s been easier to break that barrier down a bit.”

On Tuesday, Mayor Jim Kenney publicly announced his support for the BDCC during a testing event at Enon Baptist Tabernacle Church. The BDCC’s initial proposal to the city requested $6.9 million to provide coronavirus testing and other related services. The city declined to confirm the exact figure the group would receive but estimated the grant would be much lower, in the range of $1 million, and that a final amount is still being negotiated. The grant will enable the BDCC to continue providing testing through the end of 2020.

Philadelphia magazine is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and economic mobility in the city. Read all our reporting here.