Rob Thomson’s Wild Ride

Last spring, the baseball lifer had quietly decided 2022 would be his final year in the big leagues. You know what happened next: big promotion, NL Championship, Red October. Now the question on everybody's mind is: Can the Phillies skipper do it again this season?

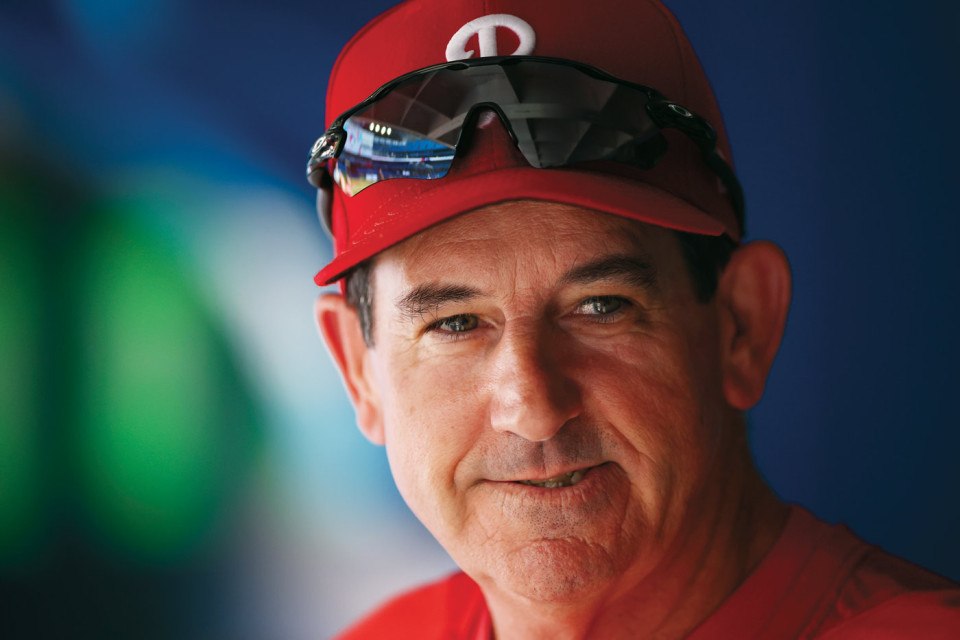

Rob Thomson at Bob Heilman’s Beachcomber, a spring-training haunt for the Phillies brass in Clearwater Beach, Florida / Photograph by Bob Croslin

The line for dinner service at the St. Francis Inn in Kensington started forming just before 5 p.m., with folks traveling from across the neighborhood and beyond for a hot meal, fresh produce, a warm drink, maybe a bag of toiletries. St. Francis sits in a gentrification zone where you can take a short walk in one direction to a brewery full of tattooed IPA drinkers or in another to the epicenter of the city’s opioid crisis. In the shadow of luxury condos going up across the street, the volunteers at St. Francis expect as many as 200 people in the span of two hours on this chilly January night. That’s nothing out of the ordinary. But even though the red “Phillies” aprons worn by a few of the servers hint that something unusual is afoot, this isn’t where you’d expect to see manager Rob Thomson.

For starters, he’s fresh off a post-season that brought baseball back from the dead in Philadelphia, taking the team to two wins away from a World Series title. Pitchers and catchers don’t report to Clearwater for more than a month. Also, Thomson is Canadian. Shouldn’t he be north of the border, enjoying a well-deserved recharge before the upcoming campaign? On the horn with a potential free agent? Giving newly acquired Phillies shortstop Trea Turner a tour of the city, or one of those oversize checks they hand to lottery winners?

This, however, is exactly what you do as the manager of the Phillies, especially now that the “interim” tag has been removed from your title. Prior to the rollicking, roller-coaster 2022 season, Thomson, 59, had spent four decades in pro baseball, including 10 years coaching in the minor leagues — which is technically a full-time job but more a love than a living — and eventually serving as a bench coach in the big leagues. That meant he was number two, the guy behind the guy, not the one at the top of the dugout steps who’s subject to TV camera close-ups. Thomson was the detail man, planning every hour of the spring-training schedule and providing the skipper with in-game support. It was the perfect job for a baseball lifer.

The manager gig, though, is literally a whole new ballgame, year-round. In December, Thomson attended the league’s winter meetings in Florida and, for the first time, had a voice at the table with ownership and the front office. Equally foreign to him is the public relations part of the role, getting out there as one of the faces of the franchise. So he signs autographs at the Oxford Valley Mall and gets an earful from a fan who’s upset the team traded Matt Vierling, and he reads books with the Phanatic at Green Woods Charter School, and he chuckles when he ends up on the big screen at a Flyers game.

On the serving line at St. Francis, next to staff and students from all-girls Mount Saint Joseph’s Academy, Thomson looks as relaxed as he does on the field. (Superstar slugger Bryce Harper says of Thomson’s unflappable demeanor: “He kind of reminds me of Wyatt Earp in Tombstone when Doc Holliday says, ‘Wyatt. You’re an oak.’”) “I’m Rob,” he says, introducing himself in the bustling kitchen to Sister Mary, a lifelong Phils fan, and Karen Pushaw, who’s been with St. Francis since 1991 and wore her blue ’08 world champions tee over a red long-sleeve for this special occasion. As the volunteers hustle, diners file in and out, and outfielder Brandon Marsh and rookie utility man Dalton Guthrie serve plates of food, Pushaw is the calm at the storm’s center. She’s got everything covered, with chicken as backup in case the roast beef runs out; when the chicken’s gone, there’s stew. Ovens are monitored, pans of potatoes are distributed, heads are counted. She’s a leader after Rob’s own heart.

After Marsh speeds over to refill a pitcher of lemonade, someone notes that Thomson picked the right job tonight. Instead of dashing from tables to the food line and clearing dirty dishes, he’s at ease manning the beef station and chatting with the other volunteers. Laid-back and casual-cool in his dark gray jeans and an untucked white collared shirt with the sleeves rolled up, Thomson is quick with a reply: “You think I’m stupid?” he says with a chuckle as his players work up a light sweat.

Rob Thomson before the start of Game 1 of the 2022 World Series in Houston / Photograph by Daniel Shirey/Getty Images

This is one of many Phillies charity events throughout the year, and while it may seem like that’s the only connection to baseball here, this scene explains why Thomson — who’s also known as Topper or Thoms or a number of other endearing nicknames — became both a player favorite and a fan favorite last season. He’s the good guy who finishes first (or at least a couple wins short of a title). He earned this opportunity through a lifetime of dedication to the game and hard, crack-of-dawn, dirt-under-the-fingernails work, and that’s about as Philly as you get. The players are the stars of the show tonight — bussing tables, trading stories with the patrons, drawing dreamy gazes from the schoolgirls. Thomson, meanwhile, asks the St. Francis staff how he can help, then quietly does his part.

“The whole city rides with Philly Rob,” says Marsh, citing another popular Thomson alias. “He shows love to the community, and it’s really cool to see how engaged he is as a first-year manager.” As for last season’s pennant-winning success: “I really believe it all started with Philly Rob. It all starts with him.”

Harper agrees: “He’s putting it all together as manager,” he tells me in a conversation later. “He’s taking the best from everybody he’s learned from but also just being himself. And it’s so much fun to see.”

Dinner ends when the clock strikes seven, and the St. Francis team shifts quickly to cleanup mode. Reps from the Phillies politely ask if all the volunteers can gather for a group photo. A couple quick snaps, and then it’s right back to the last guests and packing up for the night. Before the group disperses, though, Rob has a request. “Let’s get one with me and Karen,” he says. Just him and Pushaw — two skippers, one a lifelong Phils fan, the other a guy from 500 miles north, trying to bring another parade down Broad Street.

Thomson is more in his element at the Philadelphia Sports Writers Association annual awards banquet the following week. He’s here at a hotel in Cherry Hill with third baseman Alec Bohm to accept the “Team of the Year” award on behalf of the Phillies and alongside a cast of all-star college and professional local heroes, including former Villanova coach Jay Wright, who knows a few things about being both a winner and a decent human being.

Before the event begins, Thomson talks to a scrum of beat writers in the VIP room. Dressed in a black suit, a burgundy tie, and a charcoal wool overcoat, with some gel in his hair and a whiskey neat in hand, he cleans up nice. But with the creases along his face and a smile that sometimes angles to a smirk, he still looks like your favorite bartender at the neighborhood pub, or the regular with the corner seat who hasn’t forgotten about the ’64 Phillies collapse.

A few days earlier, he’d spoken in the clubhouse, and a reporter asked about a recent poll ranking the most handsome managers in baseball, in which he finished second. “I said, ‘Hey listen, Michele, you know how lucky you are? I’m the second-most-handsome manager in baseball,” Thomson said, referring to his wife. “And she was cooking dinner, and she didn’t miss a beat. She turned around and she said, ‘So everybody else must be tied for first.’”

He’ll give the media more material during his award speech at the banquet, with a story about a friend who coached against the Phillies in the playoffs and said his team couldn’t think straight amid the seismic noise at Citizens Bank Park. “‘Playing in your stadium, with the way you guys played and with the electricity of the fans — it was four hours of hell,’” Thomson recalls being told. He speaks for less than four minutes and raves about his fellow honorees, all the great teams in town, his players, his coaches, the front office, the fans. Thomson only looks inward once: “It’s been a long time since I’ve been this excited to get to spring training.”

In his office at the ballpark the week before, Thomson was fully in his element, even with all the boxes that were headed to Florida and little more on the walls than four framed newspapers from that golden, glorious season in 2008 — presumably leftovers from a previous regime, since Thomson was a Yankee back then. Aside from the mini fridge with a bottle of Dom Perignon champagne gifted to him by the players after his first win as the Phillies’ manager, the room looked like it belonged to a guy who wasn’t sure he’d be in it past October. Sitting on a black leather couch instead of behind his wide oak desk, Thomson leaned back and talked about interacting with the fans these days. “I get a lot of thank-yous, and I feel uncomfortable with that, because this was entirely an organizational win,” he said, then caught himself. “It wasn’t a win, because we didn’t win the whole thing. That’s our next goal. But the success we had this season was completely organizational. So when somebody says thank-you to me, I hope they mean ‘Thank you, Phillies.’”

Of course, the Phillies’ success story is also Thomson’s story, which is the very definition of luck as the intersection of hard work and opportunity. “He’s a very, very good baseball person; he’s a very humble person,” says Phillies president of baseball operations Dave Dombrowski, who speaks with Thomson daily during the season. “But people shouldn’t take that humility as someone who’s not confident in what he’s doing,”

Rob Thomson speaking with the media ahead of a July game against the Blue Jays in his native Canada / Photograph via Getty Images

Growing up in the small town of Corunna, Ontario, just across the border from the U.S. and a little over an hour’s drive from Detroit, Thomson fell in love with baseball through his father and two older brothers, one of whom was signed by the Montreal Expos. Rob was swinging a bat at age five and eventually ended up catching and playing third at a community college in Michigan for a fellow named Dick Groch, who would later work for the Yankees and convince them to sign a tall, skinny kid from Kalamazoo named Derek Jeter.

Thomson earned a scholarship to the University of Kansas, where he still holds the school record for single-season batting average, and was drafted in the 32nd round by the Detroit Tigers in 1985. After three unremarkable seasons in the minors, he was ready to hang up his cleats when Tigers director of player development Joe McDonald — who today has six World Series rings — saw potential in him as a leader and offered him a coaching job, along with a warning. “‘Before you take this job, understand one thing: You have crossed over the fence,’” recalls Thomson. “‘You are not a player anymore, and you will never be a player again. And it’s not about you anymore. It’s about the players. If you live with that, you’ll be fine.’”

Thomson took McDonald’s advice to heart and transitioned to coaching in the Tigers system. As in most of his major league career, it was the off-seasons that would define him as much as anything he did in the dugout or on the field. Instead of spending the winter relaxing at home with Michele in their tiny hamlet outside Stratford, Ontario, Thomson would pick up jobs like laying drainage tile in farm fields to stay in shape and earn a few bucks, since Michele sometimes made more waitressing than her husband did in baseball. (During one season with a Tigers affiliate in Ontario, his salary was $6,000.) “I thought, ‘Holy hell, I have a good one here,’” Michele says. “Here’s a guy who’s hoping to make it to the big leagues. He’s out in the freezing cold and up early in the morning. He was willing to do whatever it took.”

After two years coaching in the minors, luck struck — in Moscow, of all places. Thomson was part of an MLB barnstorming tour to cultivate future ballplayers overseas and ended up reuniting with his old coach, Dick Groch, who was on the Russia trip representing the Yankees. “Robby was realistic about his baseball abilities,” says Groch. “But it was the other dimension. Can he handle failure? How tough is this kid? The organization, the commitment, the communication skills, the way he handled his everyday life … There are a lot of guys that have the talent, but they don’t have that second component. He was constantly wanting to learn. A lot of kids take BP and then go home. He would want to have conversations about the game. It wasn’t just for two and a half hours — it started before and continued after.”

Groch asked what Thomson was doing the following year. In 1990, he joined the Yankees as third-base coach for their class-A team in Fort Lauderdale. Fourteen years later, after countless road trips between Canada, Florida and New York and toughing it out through long stretches without seeing his wife and two young daughters, Thomson was promoted to the Yankees’ big-league coaching staff. He ran spring-training operations for manager and future Hall of Famer Joe Torre, who coined the nickname “Topper” as a nod to Thomson being on top of every preseason detail and his reputation as the first man in and last one out each day. Remarkably, given his easygoing persona today, that routine began because Thomson felt so uncomfortable talking to people that he’d show up early so he could work alone. One year, Yankees owner George Steinbrenner arrived at the ballpark at dawn and was surprised to see Thomson already there (legitimately working, not a George Costanza situation). Thomson’s father had just passed away, and he’d flown back from Canada to Tampa and gone straight to work. Steinbrenner was moved to tears by his devotion and talked about losing his own dad.

Torre’s successor, Joe Girardi, elevated Thomson to the role of bench coach in 2008, and when Girardi fell ill that year, Thomson managed two games, becoming the first Canadian to lead a major league team since George Gibson with the Pirates in 1934. The following season, Thomson stood in the visitors’ dugout in South Philadelphia during the World Series, which the Yankees won in six, beating a Phillies team that was arguably better than its championship squad from the year before. “If you’re doing your job well, you draw from the people you’ve been around and see what works,” says Ruben Amaro Jr., the Phillies GM from 2009 to 2015. “He’s done that with Joe Torre, with the mentors he had, especially being in the Yankees organization. Then you have to be your own person. The beauty of Rob Thomson is that he’s just Rob Thomson. He’s a regular guy who loves the game and dedicated himself to the game.”

Thomson expected to retire in navy pinstripes. Over the years, he’d had a handful of interviews for open managerial positions, but because the Yankees were almost always in a post-season run, he was reluctant to leave the club or to do anything other than his Topper thing — spending every waking hour strategizing on winning the next game.

Phillies fans, this might be hard to accept, but you have two ghosts of the recent past to thank for Thomson’s move from the Bronx to Broad and Pattison: former GM Matt Klentak, and former manager Gabe Kapler. Say what you will about the tenure of the latter — a coconut-oil aficionado with a penchant for philosophizing and single-digit body fat — but Kapler, with support and guidance from Klentak, wisely built a coaching staff that was strong in areas he wasn’t, namely, experience and instincts rather than analytics. As Kapler told me before his first season in 2018, Thomson was “a really engaging, smart, warm individual, but rooted in what he’s seen in the Yankees organization to balance out my evidence for everything. Let’s debate the shit out of it and come out of the room with the best possible answer and outcome for every given situation.”

With no clear route to the manager’s seat with the Yankees, an appreciation for what the Phillies were trying to build under John Middleton’s leadership, and a manager in Kapler who needed his baseball mind, Thomson decided he couldn’t pass up the opportunity to join Kapler’s staff as bench coach. He thought that gig would be his last. But in 2019, when Kapler was let go after two seasons and Thomson’s old friend Girardi was hired to replace him, his prospects changed.

An in-ground backyard swimming pool, complete with a pool house for entertaining: Back in spring training last season, when Girardi was still managing the Phillies, that was Thomson’s big plan for the fall of 2023. He’d break ground on the project at his home in Stratford so it would be ready for the following summer, when he’d have plenty of free time to enjoy it. What only a handful of people knew in Clearwater a year ago was that Thomson was planning to retire at the end of the ’22 season. “I’ve been doing spring training and advance work and being the bench coach for so many years, I felt like I was starting to get a little stale,” he says. “And because of that, maybe the players were getting stale with the information that I was giving them. I thought that there was probably somebody out there — younger, newer, better ideas.”

Yet even in his brief tenure with the Phillies, Thomson was still adding pages to his leadership playbook. During the previous four seasons, Thomson worked for two very different managers and learned from them both. Kapler had a love for data and a gift for connecting with players on a personal level. “Culture” was never discussed with the Yankees — it was carved into marble there, defined by 27 World Series titles — but here, it was something Kapler spoke about often. From Girardi, Thomson drew on the veteran’s experience as a four-time champion, including three as a player. The pair had a near-telepathic connection, with Thomson knowing what moves Girardi would make and what he needed in support. The COVID season took a lot out of everyone, physically and emotionally. Thomson figured Girardi was here for the long haul, and he had one ring already. What else was there to teach, to learn, to do?

Everything changed on June 3rd. Despite new big-ticket free agents on the roster and a thirst for snapping a decade-long post-season drought, the Phillies were a miserable 22-29, losers of seven of their last 10. Girardi was fired. Dave Dombrowski looked at four members of the staff as possible replacements — including infield coach Bobby Dickerson, hitting coach Kevin Long, and third-base coach Dusty Wathan — but Thomson stood out. “When you make a change at that time, you want an immediate impact,” says Dombrowski. “You could see there was a lot of respect for Rob from everyone around the club. And we needed a different voice.”

Thomson took over, and the team won his first game as skipper, 10-0 against the L.A. Angels, then the next seven in a row. “It was that breath of fresh air,” says Harper. “He just told us he wanted us to play the game and be ourselves. He had all the faith in the world that we were going to get it done.”

First baseman Rhys Hoskins says the players were surprised by how poorly they performed early in the season and believed in Thomson from the start. “Thoms is not a rah-rah guy,” he says. “He doesn’t sugar-coat anything, but I think that helped us be us. He wasn’t blowing smoke. He was very real — ‘We have a lot of work to do, and we know what we’re capable of.’ We trusted him.”

After consulting with his coaching staff and the front office, Thomson made a few immediate changes. He stabilized the lineup so the hitters knew their roles, day in and day out. For the bullpen, he did the opposite — without one clear-cut closer, he used pitchers in positions he felt gave them the best chance to succeed and held daily meetings to discuss strategy. Where Girardi had been reluctant to give younger Phillies consistent playing time, Thomson turned infielder Bryson Stott, outfielder Matt Vierling and third baseman Alec Bohm into productive regulars. “We just let go and be ourselves and cause a lot of ruckus in the dugout,” says Bohm, one of the “Day Care” members, as the junior players became known. “Nobody’s like, ‘Hey, shut up and sit down.’ I think that’s why you saw a lot of young guys come up and perform well last season.”

Brandon Marsh, who joined the Day Care crew when he was acquired in August, calls Thomson the “silent assassin” for his steely dugout demeanor: “You see that look on him during the game, and when it comes time to make a decision, he’s on it. He’s not saying much, but I know there’s a billion things going on in his head.” Marsh says he knew he’d like his new manager during his first game with the Phillies, when Thomson lightened the mood during a rain-out with a wisecrack. His notoriously dry humor is a useful tool. “Sometimes, guys don’t know if he’s joking or not,” notes Hoskins. “He says something serious and you’re not sure if it’s serious. That’s perfect for a clubhouse of 25-, 30-year-old men. He keeps us on his toes. And he can laugh at us, too.” Of course, the clubhouse isn’t a comedy club, and Thomson’s no pushover. “I always tell players,” he says, “there’s a difference between having fun and fucking around. And I know what the difference is. Don’t fuck around. But let’s have a lot of fun, because you got to have fun.”

Thomson’s instincts were only wrong in terms of feeling like his best coaching days were behind him. “The thing that makes him so great is, he understands it’s all individual,” says Bohm. “What works for this guy might not work for that guy. Little stories about, ‘Hey, you know Jeter went 0-for-20.’ Those subtle, friendly reminders were like, ‘It’s all right. It’s just a game.’”

With a bum elbow, Harper spent most of the season in the designated-hitter role, which meant more time in the dugout with Thomson — his seventh manager in 12 years — than in right field. “The thing I love about Thoms is his stories,” Harper says. “I love to learn the history of the game, the in-game stuff. I got to see all the decisions up close, because I’d be standing there. He just trusts those guys to do their job. Having a manager that really loves his guys and his team — you want to play for a guy like that. You want to give your all for a guy like that.”

Despite digging themselves out of that early hole and into a playoff spot, the Phillies weren’t immune to the dreaded “September Swoon” that’s plagued the franchise each of the past several seasons. The team lost 10 of their last 14 to finish the month with a tenuous half-game lead in the wild-card race, then clinched a playoff berth with only two games left. The team’s limp into the post-season and a three-game series on the road against St. Louis didn’t inspire confidence, at least not outside the clubhouse. Hoskins remembers Thomson addressing the team ahead of the Cardinals tilt.

“He just had this confidence, even though we were skidding at the end of the year, that things were going to change,” he says. “He didn’t say we were playing with house money, but that was the sense. We got this monkey off our back, and he was excited for us.” Thomson says his strategy was simple: “I thought once we got in, everybody would relax, and we’d start playing again. And we did.”

Rob Thomson congratulating Bryce Harper after beating Atlanta in the Division Series / Photograph via Getty Images

You know the story from there: sweeping St. Louis in the wild-card round, then bringing playoff baseball back to Philly, complete with bat spikes, towering bombs, and a raucous crowd that triggered decibel warnings. Thomson is still in awe of that atmosphere, which is remarkable given his playoff experience with the Yankees. He says all the free agents the Phillies courted in the off-season mentioned how impressed they were by the energy of the ballpark. “Our guys in the trainer room when Harper hit the home run against San Diego?” he says. “The hot-tub water was rippling. They thought the windows were coming through, it was so loud.”

Throughout the playoffs, Dick Groch would send Thomson his own scouting report for each game. His general advice was to “dance with the girl who brought ya,” as Groch describes it: Don’t change who you are or how you strategize just because the stage is bigger, the lights are brighter, the heat is unbearably hot. In the World Series, the day after one of his bullpen guys had a shaky outing, Thomson would ask how he felt out there, and if the answer was “Nervous,” he’d say that’s perfectly natural, and it’s going to be much better the next time. He wasn’t blowing smoke. He believed it.

Everything worked until it didn’t. The Phillies’ bats fell cold against a lethal Houston Astros pitching staff. Then, in the deciding Game 6, Thomson pulled ace Zack Wheeler in the sixth inning for lefty José Alvarado, who immediately gave up a three-run homer to Yordan Álvarez. Wheeler made it clear afterward that he disagreed with the decision to pull him. But to a man, the rest of the Phillies expressed the same belief in Thomson’s judgment then that they did all year — an unwavering trust in their leader that’s rare over the course of a marathon baseball season.

Thomson still thinks about that moment — perhaps the most important call of his brief managerial career. “There have been plenty of decisions during the course of the year where I went home at night and I go, ‘You’re an idiot. Why would you do that?’ Something in the game nobody even noticed. Whereas in the World Series, that decision — I’ve learned that I can live with it. That’s something going in, I wasn’t quite sure if I could do that.”

After the wild-card round, the Phillies signed Thomson to a two-year deal, so he’ll have to wait a few summers to enjoy a dip in that backyard swimming pool. If there’s an off-field moment that sums up this unpredictable journey for a guy who nearly retired, it was Game 5 of the National League championship. The Phillies ousted a tough San Diego team and were headed to the Fall Classic, an outcome few observers would have envisioned before the playoffs. As they celebrated on their home field, all of the players’ wives and girlfriends emerged wearing “I Ride With Philly Rob” t-shirts — a tribute organized by Hoskins’s wife, Jayme, much to the surprise of both Thomson and Michele, who teared up at the gesture. Dombrowski says Thomson’s baseball acumen is one part of his success and his promising future as the team’s leader. “The other part is, he’s just a really good person,” he adds.

Sitting in his office at the ballpark, Thomson recalls walking back to his Center City apartment last June after meeting with Dombrowski and, following some considerable hesitation, accepting the job as interim manager. Topper’s mind started tallying all the tasks he’d need to tackle, like one of those CVS receipts that just keep going: meetings with players, meetings with the staff, talking to the press, schedules, opponents, strategy, stats. He noticed the people on the busy sidewalk and knew that in a few months, the anonymity he enjoyed in this moment would vanish. Soon, at least some of these passersby would give a “Go Phils” or ask for a selfie, if he did his job right, or a “You suck” or worse if things went south. My life is going to change now, he thought. I’ve got to be ready for it. He couldn’t imagine being so close to a title in October, or turning the city back into a baseball town, or, most improbably, his quantifiably handsome face showing up on t-shirts.

Now, instead of been-there-done-thats, this spring holds more firsts for Thomson. He and Michele are buying a home in the city. This will be his first Clearwater tour of duty where someone else is meticulously planning the details while he’s having dinner with city muckety-mucks or meeting with team executives. “I may not be able to get in there at 2:30 or three in the morning,” he says, looking genuinely concerned about sneaking in a workout and starting the day sufficiently early. “It might be 4:30, something like that.”

Climbing up the mountain again will leave little time for sleep. Thomson’s team faces stiff competition from a stacked NL East, with the Braves and Mets having improved their already fearsome rosters in the off-season. “In our division, no one is picking us to win,” says Dombrowski, who, prior to joining the Phillies, served in the front offices of three franchises that reached the World Series a total of four times. None of them made it back the next season. “It’s very hard to do,” he says. “When you look at what we did last year, you have to get to the post-season, which is not easy. And you have to beat good clubs. Things happen; obstacles come your way.”

That’s baseball. You need some lucky breaks, like the NL instituting the DH position ahead of a season when your best hitter couldn’t play the field, or MLB adding an extra wild-card team, without which the Phils would have missed the playoffs yet again. But Amaro cautions against underestimating Thomson’s impact on the team, based on what he accomplished last season. “I think it’s unprecedented,” he says. “I’ve never seen anything like it. My feeling is, a manager, if he makes significant changes, can have a five-to-10-game swing on the positive side. This guy had, like, a 20-game swing. Rob just needs to be Rob, and I don’t think that’s going to change.”

Phils skipper Rob Thomson out on the town at spring training / Photograph by Bob Croslin

Thomson says his priorities for this year are adjusting to the new rules (including a pitch clock and restrictions against the defensive shift), getting off to a fast start — a change from the Phils’ recent sluggish opening weeks — and staying hungry. “We can’t be complacent,” he says. “And I don’t think we will, not with this group. If we had won the World Series, I would have been really worried about complacency. But I think now they’ve got a taste. Now they really want it.” He also demands that his staff keep Philly Rob accountable. “I’ve seen a lot of people in this game that had success, and they think they got it figured out,” he says. “I need to make sure I’m not one of those guys. They need to be completely honest with me. I want their honest ideas, not just, ‘Yeah, you’re right, Thomson.’ I never want that.”

But first, before another drive from Stratford to Clearwater in a few days, there’s the St. Francis event tonight, the sportswriters’ awards next week, an induction into the St. Clair County Community College hall of fame that follows a visit to the University of Kansas to speak at the baseball team’s season-opening banquet last week — the list of obligations and novel experiences goes on. Then there’s something old that feels suddenly new again. “I can’t wait to get to spring training, I really can’t,” he says. “I’m re-energized. The last couple of years — and this is what kind of led me to think about retiring — I wasn’t really excited about going to spring training. I’m really excited. And it’s just because of the group of guys in there, the players and our coaching staff.”

Despite last year’s success and arguably a better roster today, hard work lies ahead — more early mornings and more tough calls to make. Baseball guarantees nothing, not even to a lifer. But Thomson is built for this. He walks out of his office to attend to more managerial duties, one step closer to the start of a campaign in which the meticulous planner, the support guy, the second fiddle, is now the showrunner from the jump. It’s more virgin territory: a full season in which he’s setting the tone, putting his vision into action rather than supporting someone else’s plan. Considering his new joie de vivre for the game and the old Topper mentality that served him so well from the farm fields of Canada to the Bronx, history suggests he’s prepared for the challenge that still lies ahead, one that’s even more daunting than winning: winning again, and winning it all, proving that Red October was no fluke.

Published as “Play It Again, Rob” in the April 2023 issue of Philadelphia magazine.