This Philly Performance Artist Just Scored a $75,000 Pew Fellowship

An interview with Jaamil Olawale Kosoko, who talks to us about Zoom fatigue, living in fear, and what he's going to do with that money.

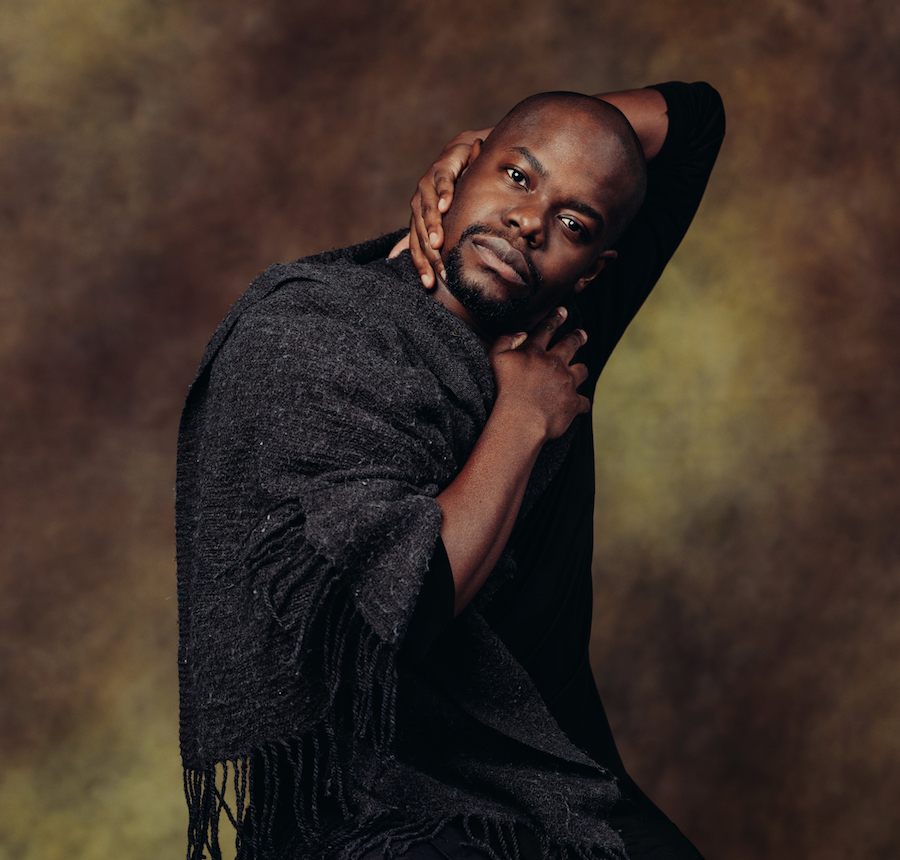

2020 Pew Fellowship recipient Jaamil Olawale Kosoko. Photo by Sarah Griffith, courtesy of the Curtis R. Priem Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC).

On Wednesday, the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage announced over $10.5 million in grants supporting artists and cultural organizations in the Philadelphia area, many of which focus on elevating historically underrepresented perspectives. Jaamil Olawale Kosoko is a recipient of one of ten $75,000 no-strings-attached 2020 Pew Fellowships. Kosoko is a Nigerian-American poet, curator and performance artist. And he spoke with us about performing and teaching digitally, 2020 fatigue, and art’s power to spur the deep reckoning he feels America needs.

Could you talk a bit about your plans for the Pew Fellowship grant and how they fit into Pew’s mission to promote the role of art in civic life?

I think, more than anything, it provides a sense of security in otherwise very unstable times. More than having an exact project in mind, I’m really looking to elevate my practice.

Digitality has always been a part of my thinking and creative practice, but at this point it really is becoming less creative inquiry and more like a mandate.

When I was writing my application, it was still at the height of the pandemic, and there was so much fear and questioning lingering in the air. And I think as we approach this recession right now, the support is really—it’s what’s going to see me through the next several years. In the end, if we’re not taking care of the artist and centering their experience, we don’t get any art from them.

How have your thoughts about the digital form changed in this world where it’s now the default medium?

I think in a number of ways it creates a dilemma. Just as much as anyone, I suffer from Zoom fatigue. I’ve become much more sensitive to the Internet, which offers this kind of connectivity but also this strange distancing. Before there was more of an opportunity to mitigate the amount of interaction I really had to digest, but now this feels a bit unbearable at times, to be completely honest. And so trying to find more of a balance — ways of being online that don’t feel as draining—is really important.

Myself as teacher and embodied practitioner — there’s so much we do in the room together that just can’t translate through this digital sphere. So that’s something I’m deeply concerned about: how do we learn to be together, to reintegrate, once this moment is behind us? I don’t have an answer, but I’m certainly working through it.

With regard to live performance—do you miss being in physical spaces with people?

Certainly, I deeply miss it. I think there’s a spiritual loss and a grief at the core, trying to confront what it means now that “in real space” is having to be translated through this kind of interference.

2020 Pew Fellow Jaamil Olawale Kosoko. Photo by Eric Carter.

I had a chance to read some of your poetry and wanted to ask you about a line: “In the absence of love we do many things.” How are you feeling about this statement in 2020, eleven years after it was first published?

I think love is something that’s lacking. The aftermath of the loss and grief is, for me, what this pandemic has exposed in a lot of ways: this lovelessness that’s so pervasive within the American project but also throughout the world. That line asks us to pull attention to the trouble, to the problem, if you will. I don’t think it answers anything, but it makes a pretty keen observation — a very personal truth gone quite public.

How does your heritage inform the art you make? How does it inform the way you look at America, or art in America?

I think traveling has taught me to acknowledge America for who she is — severely schizophrenic with a lot of healing to do. So much of the current project I’m doing now, American Chameleon, is a critique on the American project but also my place in it, and what survivalist tactics or strategies I’ve had to learn in order to survive this land—this place in direct opposition to my lived experience.

A lot of my work rises from this uneasiness, this sort of friction. I think about: where do we begin the story of America? For some people it starts with the Civil War, maybe, or for some with Columbus. For some it starts with indigeneity, understanding this land before colonization.

This land is beautifully ill with a lot of unacknowledged history and woes, and I hope we can allow for an administration that can lead us toward doing some of that deep work that’s needed.

One thing I can say about Obama is I felt fairly secure, for the most part, under that administration. I don’t remember the same amount of fear I have literally just going out the door. It can be enough to really just break into tears. I’m grateful I can wear a mask and shades so that no one sees me cry. It’s a strange world.

For a complete list of 2020 Pew Fellowship recipients, go here.