What Happened to Marie Noe, the Philadelphia Mother Who Murdered Eight of Her Babies?

The West Kensington woman’s case stunned the world in 1998 — when a Philadelphia magazine investigation led her to confess to the mysterious deaths of her babies in the 1950s and ’60s — but had faded from memory over the years. Here’s how her story ends.

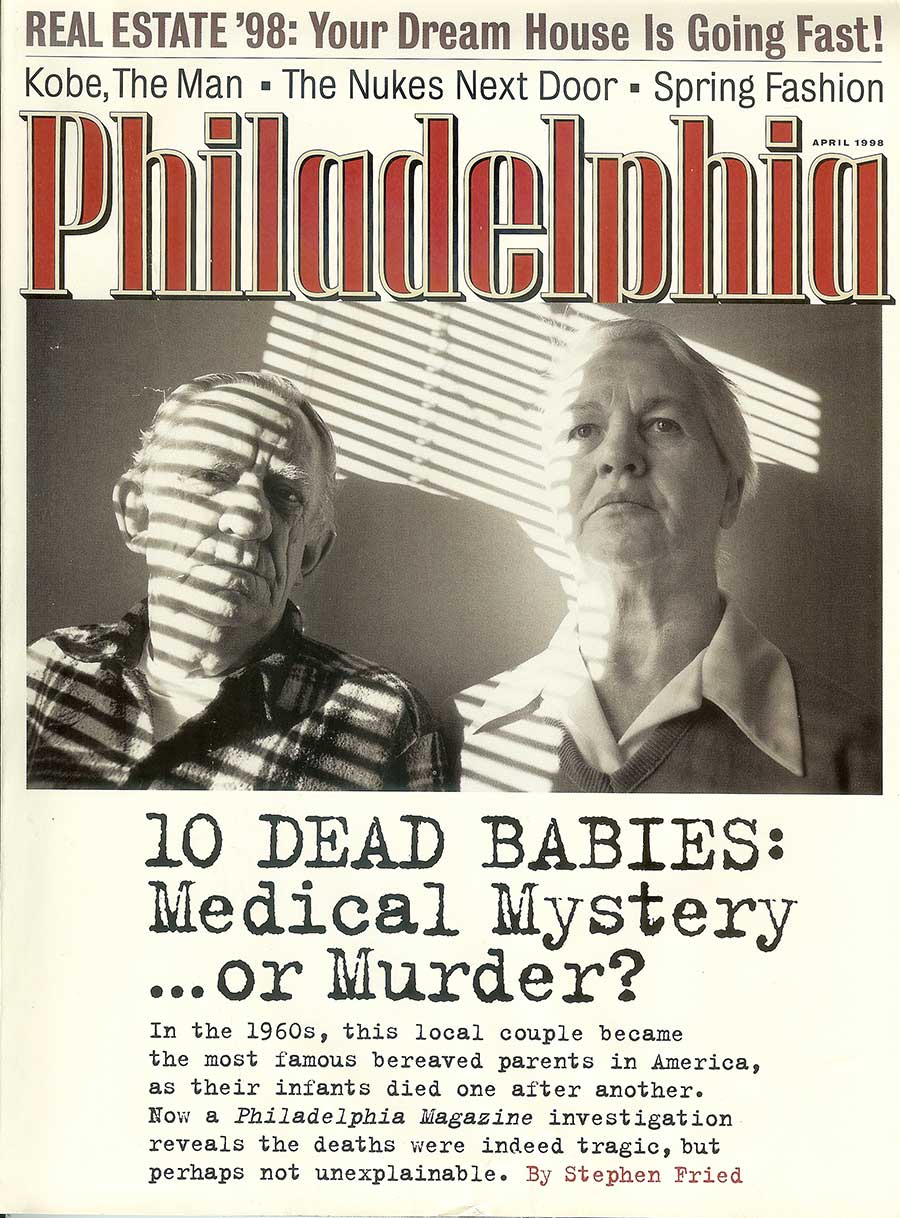

Marie and Arthur Noe on the day author Stephen Fried first interviewed them in 1997. Photograph by Stephen Fried

On Sunday, June 8th, at 1:27 p.m., somebody posted a question on Reddit that immediately transported me back 23 years:

“Does anyone have any idea what happened to Marie Noe?”

After three hours of random comments from readers who were also curious, but couldn’t find any answers online, one Reddit member came right to the point.

“If she’s not dead yet,” he wrote, “she should be.”

“Whatever happened to Marie Noe” is a question I’ve been asked, by so many people from so many places, since the spring of 1998. That’s when a 13,000-word investigative story I wrote for Philadelphia magazine, “Cradle to Grave,” reopened the 30-year-old case of the 10 babies of Marie and Arthur Noe, all of whom died mysteriously between 1949 and 1968, supposedly of a new disease called Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).

The opening spread of our first Marie Noe story in April 1998.

The day the magazine came out, Marie Noe, then 71, was taken in for interrogation by the police. She confessed, and when the Philadelphia D.A.’s office announced charges against her a few days later on eight counts of murder — two of the children were deemed to have died of natural causes — the story was covered worldwide. So was her guilty plea several months later, and then her controversial plea agreement and sentence. She was allowed to avoid prison if she cooperated with an unprecedented study of her and her case by a dream team of international experts, the equivalent of donating her brain to science while she was still alive.

But the study never happened. So, after her conviction in the largest maternal homicide case in recorded history, Marie Noe did what she had been doing for years before I first came to interview her. She sat in her worn home on North American Street with her husband Arthur and a small menagerie of dogs and cats they yelled at for making a mess or blocking the TV. They sat that way for another 11 years, until Art died just after Christmas in 2009.

Several weeks later, Marie gave her last, brief interview. She was 81 and in poor health, but predicted, “I got a lot of time left.”

It turned out she had six more years. Marie Noe died on May 5, 2016, at the Cheltenham Nursing and Rehabilitation Center on York Road.

I got this information with the help of retired FBI agent William Fleisher, which is fitting. Fleischer had assisted with the original investigation, as part of his work as co-founder of the Vidoqc Society, the Philadelphia-based international organization of retired law enforcement and forensic experts who help solve cold cases. He first connected me with Larry Nodiff, then a sergeant running the special investigations unit of the Philadelphia Police (and now a staff inspector) who agreed to quietly re-open the case while I was investigating it.

Marie and Arthur Noe on the cover of the April 1998 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

It’s a little unclear where Mrs. Noe spent her last years. Her house on American Street was sold in 2013, and there’s an address for her in Darby — perhaps with a friend or relative — before she moved to the nursing home just months before her death. Marie died three months short of her 88th birthday, and had lived 48 years since smothering her tenth and final child, five-month-old Arthur Joseph Noe.

This is, finally, where the worst maternal homicide case in recorded history ends. I’m not calling her family or neighbors to find out more about what happened. In fact, after she confessed in the summer of 1998, I never tried to interview her again. She had been, during the months I worked on the story beginning in the fall of 1997, unusually cooperative and open to speaking. She always said she wanted to know the truth about what happened to her babies. And even though we spoke openly, several times, about old cases like hers — originally blamed on “crib death” and then SIDS — being reopened as murder investigations, she seemed okay with that. I still have the picture I took in their living room the day I met them, when I still wasn’t sure if they were the victims of a tragedy, or the perpetrators, or both. I had never written a murder story before (and have never written one since).

While interviewing the couple, I was also interviewing the team who had investigated them in the 1950s and ’60s, and were crushed when the Noe file was shut in 1968 with no arrests. They were hoping to finally close the biggest case of their careers before they were gone.

Flamboyant Montgomery County coroner “Homicide Hal” Fillinger had been diagnosed with cancer. His former colleague, renowned pediatric pathologist Molly Dapena, was losing her memory to early Alzheimers. And the investigator they had worked with on the case, Joe McGillen — who kept copies of the Noe files stored in his garage for decades hoping someone would reopen it — was long-retired. McGillen, a former insurance investigator and minor league scout for the Phillies, was taking care of his terminally ill wife, Elaine, who had only months left.

Miraculously, Elaine lived long enough to see her husband’s lifelong obsession with the 10 babies of Marie Noe lead to a high-profile conviction. Besides all the media coverage, Joe, Hal, Molly, Larry Nodiff, two of his police interrogators, and I received medals from the Vidoqc Society at a black-tie dinner.

We lost Homicide Hal in 2006 at the age of 79; we lost Molly Dapena in 2012 at the age of 91; we lost Joe McGillen in 2015 at the age of 89.

And now Art and Marie Noe are gone.

I always felt bad for Art; he struggled with alcoholism, and he was so blindly in love with his wife that he went to his grave believing she couldn’t have killed their kids. In a way I felt bad for Marie, as well. It was obvious from her medical records, and even from her own way of telling her life story, that she suffered from a developmental disability as well as hormonal and psychiatric disorders, that brought on post-partum psychosis in the weeks and months after each birth. She also struggled with alcoholism. But disease and disability do not excuse murder. They begin to explain how, not why.

In the end, it is all about the babies whose lives she took. The oldest of them, Richard, would have been 71 this year; the youngest, Arthur, would have been 53.

May their memories be for a blessing.

Stephen Fried is an award-winning journalist and best-selling author of seven nonfiction books who teaches at Penn and Columbia. He spent 18 years on staff at Philadelphia magazine and is now a writer-at-large. He lives in Philadelphia with his wife, author Diane Ayres.