In 2014, a Havertown Eye Doctor Went to Jail for Growing Pot. Now He’d Like His Life Back

Paul Ezell says he was growing marijuana to help his wife manage pain. But what happens now that medical marijuana is legal?

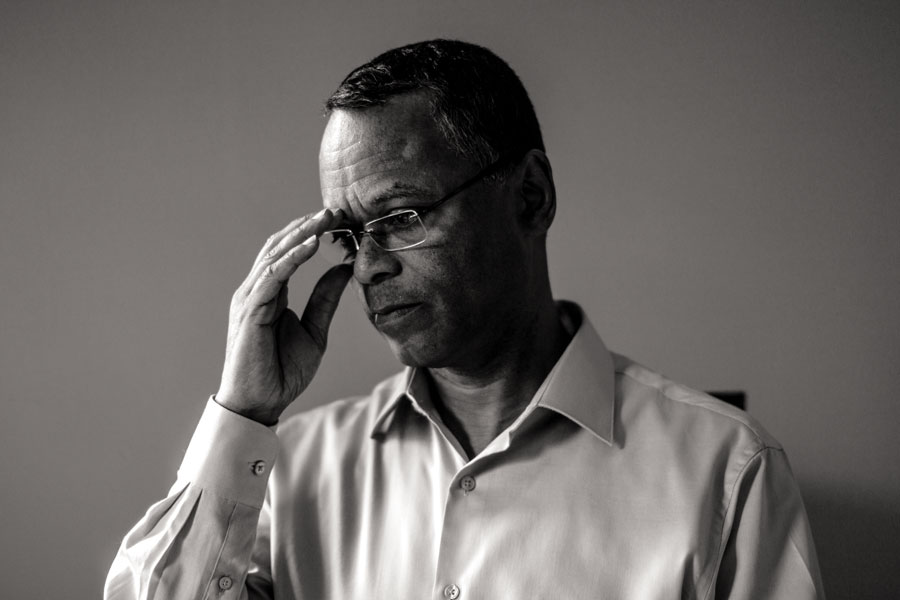

Six years ago Paul Ezell was sent to prison over the marijuana plants in his basement. Now that medical marijuana is legal, he’d like his life back. Photograph by Neal Santos

Update, May 27, 2021: On March 5, 2021, the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons voted in favor of Paul Ezell’s pardon application. And on May 26th, Governor Tom Wolf signed Ezell’s pardon. “Here’s a doctor of 30 years who had not so much as a speeding ticket, and then his whole life is ruined for giving his wife medicine that is now legal in Pennsylvania,” Lieutenant Governor John Fetterman, who championed Ezell’s case, said in a release. “This is a prime example of the destructive power of reefer madness.” The case of Ezell’s daughter, Victoria, will be heard by the Board of Pardons in June.

Original story: It’s a Wednesday — April 23, 2014 — before sunrise, on a quiet residential street in Havertown. Paul Ezell, lying in his bed, asleep, hears commotion downstairs — the sound of bumping around on the first floor of his three-story home. It wakes him up as he lies alone in the queen-size bed that he and his wife, Jayne, once shared.

He still thinks of her often — of Jayne. Of her as a lover, as a person, as a mother. He sometimes feels as though she’s still there with him, lying beside him. Now, startled awake, he wonders — in a dream state, forgetting, somehow, in this moment, that she’s been dead for nearly a year — whether the sounds have awakened her, too. Of course, they haven’t. But how long does it take, really, to erase the sensation of the woman who’s slept by your side for 26 years? The only woman you’ve ever loved. The mother of your child.

The commotion continues — bump-bump-bump-thump-thump — beneath him. He tosses right and then left, eyes still closed. Slightly more conscious now, he thinks the noise must be his 23-year-old daughter, Victoria, returning home early in the morning.

He lifts his head, looking left, over to his alarm clock. It reads 6:30.

Dammit, he says to no one. But there’s more time to sleep, he thinks, closing his eyes again. He puts his head back down on his pillow and —

“Show me your hands!” a man yells out of the darkness.

Paul has no idea what’s going on. Startled, he sits up, forcing his brain into action. A flashlight shines brightly in his face, initially blinding him, then illuminating the scene around him. A German shepherd sniffs the perimeter of the room. Paul’s mind races as he looks at the dog. Then he realizes: He’s surrounded. There are at least a half dozen officers there, shouting into his face.

SHOW ME YOUR HANDS!

Paul still isn’t quite clear about what’s going on.

“I can see that they’re wearing uniforms,” he recalls. “And you know what I thought? I thought I’d had a stroke. I thought they were going to say, ‘Can you see how many fingers I’m holding up’ or something like that. Because I’ve been that guy, you know, checking people’s pupils.”

That’s not an unreasonable thought. What else would cause a swarm of armed police officers to invade the bedroom of a successful 58-year-old ophthalmologist working at a thriving private medical practice? A vaunted member of the community. Paul C. Ezell, MD. Affiliated with St. Mary Medical Center in Langhorne. Degree from the University of Michigan Medical School. Practicing medicine for more than 30 years.

“And the thing is, I should have been able to figure out right away what I’d done, why they were there,” he says. “They said, ‘We’re here to serve a warrant’ — a search warrant on my house.”

Slowly, reality begins to dawn on Paul.

The plants.

About two weeks earlier, investigators at the Haverford police department received a tip that a doctor was growing weed at his residence on Sagamore Road. The tipster added — without proof, and in a charge that would never be pressed in court — that the doctor had been selling the harvest to his patients. The tipster gave Paul’s name and address. Cops then snooped around Paul’s home, in secret, and rooted through his garbage. There, they discovered evidence that raised eyebrows: trimmings from cannabis plants. So they got a search warrant.

Downstairs, cops descend into Paul’s finished basement two floors below. In a corner of the cellar, in a walled-off room behind a white door, they discover a full-blown grow operation: 28 plants in total, sprouting from soil in black planters. After searching the entire home, they find marijuana clippings in plastic containers. Grow lights and fans. They find a Hydrofarm water pump, a scale, plastic bags and multiple bongs. About $1,300 in cash. Paul has a couple computers that the cops seize, along with a copy of Maximum Yield, a magazine about growing marijuana. This is enough to charge Paul with a litany of crimes: conspiracy to manufacture and distribute a controlled substance. Multiple counts of paraphernalia possession. Intentional possession of a controlled substance by a person not registered to possess it. Probably more.

Paul makes a mental list of what he’s amassed in his basement. He also runs through the charges he’ll likely face.

“So I bring my hands up,” he recalls. “And I just say, ‘Are you sure you aren’t making a mistake?’”

On a wintry Saturday morning in January, Paul’s got on a dark green button-down shirt with long sleeves rolled up. Faded black jeans, black socks, no shoes. He wears his black hair short, and streaks of white run through it — not surprising for a man who’s 64. He fusses nervously, absently, with a gold wedding band on his left ring finger and stares forward through dark brown eyes whose pupils are surrounded by coronas of hazel green.

As he lounges, arms stretched out behind him on an tan couch in a modest Upper Darby rowhouse, Paul tells me he asked himself that same question years earlier — Are you sure you aren’t making a mistake? — when he began growing pot in his basement for his dying wife. And when he asked, the answer was a resounding no: He wasn’t making a mistake.

That makes sense, he says, when you consider that less than two years after his arrest for producing medical marijuana for his wife, Pennsylvania’s state legislature legalized it. The answer also makes sense, he says, if you look at his life and how he ended up where he did.

Hailing from the racially segregated Detroit suburb of Inkster, Michigan, Paul was the youngest child in a four-sibling household. The Ezells lived right on U.S. Highway 12, Michigan Avenue, which was the dividing line between blacks in the neighborhoods south of the thoroughfare and whites to the north. But the Ezell children went to school with the white kids, in the better schools. It was a choice that Paul’s dad made in part based on his own experience fighting segregation, fighting for a fair education himself.

Paul’s mom and dad met while attending Michigan State University in East Lansing — a couple of educated black people in a sea of whites in the 1940s. Which wasn’t easy. Paul’s dad, William Ezell, made sure to avoid sending his photo along with his college applications — a way to ensure he’d be seen for his grades and qualifications rather than his skin color. He became a veterinarian. His wife, Ina, stayed home to raise the kids.

Paul showed an aptitude for learning early on.

“He was about six when he called me outside to the driveway to watch one of his experiments: He sprinkled salt on a slug,” Paul’s sister, Ruth Ezell, says. “As it shriveled and died, he explained to me the process of osmosis that led to the creature’s demise. It’s no wonder one of our cousins nicknamed him ‘the Professor’.”

Paul read a lot, according to Ruth, and he was precocious. “There were two separate incidents I learned of when he was in middle school,” she says. “In both, he questioned the accuracy of something the teacher said. One teacher responded, ‘If you know so much, you get up and teach the class’ — which Paul did. In the other, a teacher was explaining the timing of a scientific development when Paul respectfully corrected him with an earlier date. The teacher took issue, so Paul returned to class the next day with a book from his dad’s library documenting that development.”

Paul was smart from an early age, but really, all the Ezell kids were. Their parents would have it no other way. The Ezells had subscriptions to Detroit’s three daily newspapers at the time, its weekly black-owned newspaper, and magazines such as Look, Life, National Geographic, Ebony and Jet. (Ruth would become a well-respected television journalist in St. Louis.)

Paul is small — five-foot-five and thin — so he didn’t play sports for larger athletes. No football. No basketball. But he’s athletic and driven. His sister brags about how Paul set a goal of earning a black belt before high-school graduation and did so in tae kwon do during his senior year.

He apparently tested well, too; both he and his sister say he turned down acceptance letters from Stanford, Harvard, and the University of Chicago, among other prestigious schools, in favor of a program called Inteflex at the University of Michigan.

As a child, Paul was torn between following his father into veterinary studies and pursuing astronomy to work for NASA. (He’s fascinated by John Glenn’s historic Earth orbit and by Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.) But medicine always intrigued him. And Inteflex was a program with an added bonus: He could get through college and medical school in six years. At the time — the early 1970s — Inteflex represented a school of thinking that suggested medical studies simply took too long.

This was in line with how Paul thought at the time — and how he thinks now. He was always eager to learn more, to learn faster, to try new ways to challenge himself. He believed he could get through medical school with no trouble. Why not pursue an accelerated program?

All his siblings had played instruments when they were younger, but Paul waited until he was in medical school. He taught himself to play jazz and flamenco guitar — and began hanging out with musicians and artists rather than his fellow medical students. That’s when he first became intrigued by cannabis. He started smoking with the bands he played with.

By the late 1970s, he was focused on ophthalmology — and the two interests intersected.

When he wasn’t going to class or making music, Paul became a hobbyist gardener, growing orchids, angelonias and toad lilies in the windows of his apartment. He became interested in all forms of plant life — including marijuana. For his final presentation in medical school — for an advanced pharmacology class — he gave a talk on the use of cannabis in medicine: “The Pharmacology of Marijuana.” He wouldn’t do anything with this knowledge at the time. But the seed had been planted.

“At least, at that point, I had an interest,” Paul says. “I’ve always found that natural forms of treatment are more interesting, more compatible with my way of thinking.”

After Paul completed medical school, he came to Philadelphia and did his residency at Wills Eye Hospital, the Thomas Jefferson University eye clinic just west of Washington Square in Center City. He eventually decided to live in the heart of Old City, on North 3rd, just above Market Street.

In his account of this period, you might think Paul would dwell on the early professional successes of a young ophthalmologist at the beginning of his career. Instead, he talks about his extracurricular activities. He was young — he’d graduated from medical school and moved to Philly when he was just 24. He studied flamenco guitar and started writing jazz-rock fusion under the name Mandelbrot Forest. He picked up audio engineering in his spare time and started recording bands in his huge loft apartment above the bars and restaurants of Old City.

He also fell in love for the first time.

Jayne Elizabeth Schank had been working as a registered nurse at Wills since 1974 and immediately took to the new resident, who was two years younger than she was. They met in 1980.

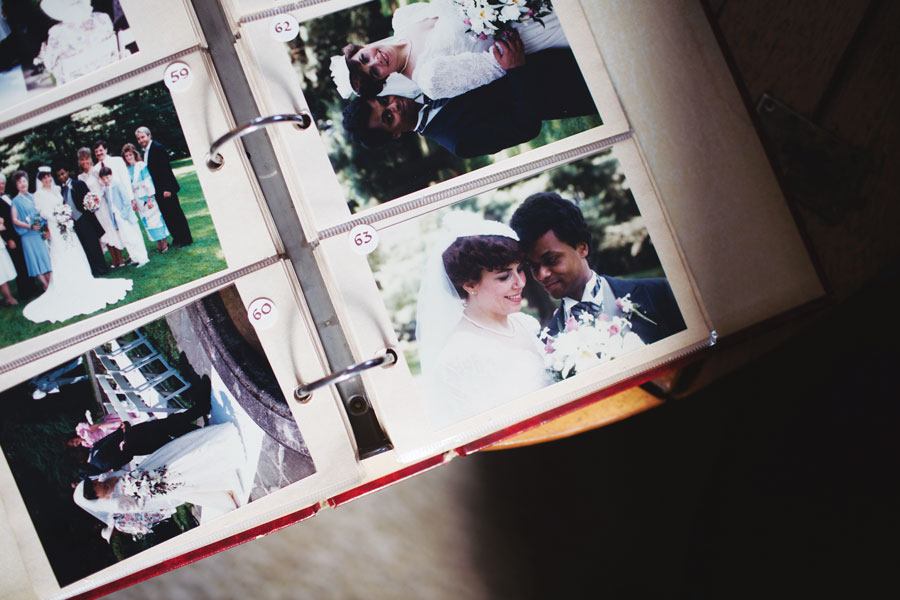

Their love affair had a high-school-sweetheart vibe to it, the result of their busy schedules. They’d pass love notes in the hospital hallways and plan moments when they could sneak time between patient visits. She moved into Paul’s Old City apartment in 1985. They married in 1987 and a year later moved to Havertown, into an impressive but not ostentatious home on Sagamore Road. In 1991 they had a daughter, Victoria. They were successful and happy.

“We were in love,” Paul says.

Photos from Paul and Jayne’s June 1987 wedding at the Wharton Sinkler Estate in Chestnut Hill. Photograph by Neal Santos

It would be that way for years. As Victoria went to public school in Haverford Township, Paul rose in the ranks, in prominence. He performed surgeries at Cooper University Hospital and St. Mary Medical Center. He began working for increasingly prestigious medical practices.

Jayne rose, too. Specializing in emergency and trauma nursing, she would eventually assist in operating-room ophthalmology at Wills and neurosurgery operations at Jefferson Neurosciences. In the early 2000s, executives at Wills promoted her to nurse manager of outpatient surgical services.

It was right around then that things started to turn sour.

Jayne began to experience severe back pain, which doctors diagnosed in 2004 as a combination of a progressive spinal disease and scoliosis.

One weekend in 2007, when Victoria was a sophomore at Haverford High School and a successful soccer and volleyball player, Jayne chaperoned her at a volleyball tournament at Penn State University. Paul got a panicked phone call from his daughter.

“She’s telling me that her mother is not well,” Paul recalls. “‘She’s acting crazy, and she’s drinking ketchup like it’s pop, and she’s making inappropriate comments, and she’s falling down.’”

As he listened, Paul says, he became “so shocked” that he “started to lose hearing in one ear.” He goes on, describing the call: “And I am saying, ‘Well, what happened? I mean, did anything happen?’” Victoria said no — that she’d left the hotel room for a short time and returned to find her mother in this frenzied state. Paul told Victoria, “Go to her purse and empty it out. Tell me what’s in there.”

Victoria read the drug names to her father over the phone: Vicodin. Codeine. Oxycontin. Cymbalta for depression. Three opiates in total. Paul now understood what was happening: “She was telling me that her mother was overdosing.”

Paul Ezell and his daughter, Victoria, pose with a portrait of Jayne in Paul’s Upper Darby home. Photograph by Neal Santos

Paul jumped into the car and drove toward State College. During the drive, he started to make connections. He recalled that sometimes Jayne would come home from her hospital shift and just crash in bed for hours — and not during the part of the day when she typically slept. “I would find her sometimes with a carton of ice cream in her lap,” Paul says. “And ice cream would be dripping down her face, all melted down, and she would be there, asleep. … ”

When Paul arrived in State College, Jayne fessed up. “She tearfully tells me that she had been on these narcotics for a couple of years,” he says.

As Jayne’s back pain became intolerable, she went to a specialist, who prescribed Vicodin. She didn’t tell Paul at the time. But about six months afterward, Paul says, she asked for his opinion: What would he think about her using a highly addictive opioid painkiller to relieve her suffering?

“I said to her, ‘You must be kidding me. There’s no way that you should go into it, because how are you going to get off of these drugs? You have chronic pain,’” he says. “Of course, at that point, she had already been on opiates for a while. She was floating a test balloon to see if I would react negatively.

“So when I reacted the way I did, she retrenched into secrecy again, because she felt like she couldn’t tell me what was going on,” he continues. “So she hid it” — until 2007, at the volleyball tournament.

Very little improved from there, Paul says. Jayne’s pain persisted. Her doctors continued to prescribe opioids. Paul just became more aware of what her doctors prescribed. “The fact is that she’s an adult and legally, she can do whatever she likes. This isn’t the ’50s,” he says. “It’s not like I can order my wife to do anything. And it’s not like I can put her into rehab.”

Things didn’t get better. In late 2007, Paul says, Jayne mistakenly faxed confidential information to someone who had previously worked at the hospital. The higher-ups took disciplinary action.

“Then, in early 2008, she came to me and said, ‘That was my last day at work,’” Paul remembers. She’d been placed on disability. “The disability was obviously related to her opiate use,” he says. “It was a disability based on the fact that she was an addict.”

What’s a doctor to do in that circumstance?

By then — late spring of 2008 — Victoria was finishing her junior year in high school and preparing to apply to nursing school. And it wasn’t as if Paul had nothing else on his plate. After working exclusively in hospital systems for decades, he’d struck out on his own as an entrepreneur and opened an ophthalmology practice about a year earlier.

Still, he considered his relationship with Jayne to be the most important thing in his life. They’d been married more than 20 years. He’d never thought of leaving her; this was a battle against addiction that they’d wage together.

Initially, he thought the battle could be won by paying more attention. They’d always sent text messages to one another during their workdays, but after she lost her job, he made sure to check in on her regularly — sometimes obsessively. “I believed for some time that just through the power of caring or talking, somehow I could help pull her out of this,” he says. That might seem naive for a practicing doctor. But despite his medical background, this wasn’t something Paul had any experience in. “There wasn’t this general societal awareness that we have today about opioids,” he says. “Nobody was talking about an opiate crisis in 2008, were they? No. That’s when they were pushing Oxycontin.”

So he relied on the doctors who were treating Jayne to do what was right.

Since Jayne wasn’t working, her days were mostly spent at home. “I worked out an agreement with Jayne and her doctors as far as dispensing her medication,” Paul remembers. “I said, ‘Why don’t I hold onto the medicine and dispense it when she needs it?’” He bought a lockbox, and before leaving for work every day, he apportioned her daily pills. “We went through 2009 using this kind of system.”

That solved the problem of potential overdoses. But Jayne was still an addict. And her pain issues persisted. She would develop tolerances, and her doctors would increase her doses, prescribe new painkillers. It was a cycle that seemingly had no end. And in taking on the role of dispenser, Paul was an active participant. He didn’t like it and began thinking of ways to break the cycle. Then, when looking through old notes, he remembered his final presentation for medical school: “The Pharmacology of Marijuana.”

“It was like a light going on,” he says. He would treat Jayne with cannabis.

When looking through old notes, he remembered his final presentation for medical school: “The Pharmacology of Marijuana.” “It was like a light going on,” he says. He would treat Jayne with cannabis.

“But I thought, I don’t want to be going out and buying pot,” he says. “And plus, I thought, I’m basically a science, engineering, tinkering kind of guy.” And he had experience growing plants.

So Paul started searching around on the internet. Making plans.

He would become a pot grower.

Sitting on his couch in Upper Darby earlier this year, Paul emphasizes that he sprouted this scheme on his own. But the concept of treating pain with cannabis isn’t new, by any means; in the notes to his 1979 presentation, Paul had cited more than a dozen specific studies from medical research institutions that delved into medicinal marijuana usage. California passed its first medical marijuana legislation in 1996. Colorado didn’t fully legalize recreational marijuana until 2012, but its residents voted to legalize medicinal cannabis in 2000. If Paul was an innovator in this regard, it was related to his willingness to try — in Pennsylvania, in late 2010, when medical marijuana wasn’t yet legal.

It just so happened there was a renowned hydroponic store — Paul asked not to identify it, to “keep heat off of them” — fairly close to the family’s home. Staffers gave him tips on growing generally, not specifically for pot. He approached the process as he would any other educational pursuit — seriously, and by taking in as much information as possible. And to hear him talk about it, it’s obvious it wasn’t just a hobby.

“I tried to take an artistic approach to it, and I got pretty good at that,” he says. “I was trying to develop strains.”

He found a medical marijuana collective in California that published information online. Members discussed crossing strains — mixing sativa and indica. “That’s the key thing in terms of the effect,” he says. “Sativa is relatively less sedating and more psychoactive in a way that’s almost somewhat speedy. And indica is more of a couch-lock phenomenon, with relatively sedative effects and more relaxing.” In reading more, Paul began to get a sense of which mix of strains worked best for chronic pain, which worked best for anxiety, and which worked best for depression. “So I actually had two strains that I obtained” — from the Netherlands, he says, without being more specific — “that seemed right for Jayne.”

He began growing. This was in early 2010, and as 2011 began, the yield showed promise. He had plants that could be harvested, so he sampled the marijuana himself. He gave Jayne some to try, and she showed a positive reaction. But she didn’t like to smoke, so Paul began the process of using a silk screen to shake loose the crystal-like cannabis particles from his plants to collect what’s known as “kief” — a powdered, concentrated form of psychoactive cannabinoids. Kief’s consistency makes it easier to infuse into cannabis baked goods — and it takes a lot of plants to produce a good amount of kief, which is why he grew 28, instead of, say, one. He began making edibles — cookies and cakes — for his wife. And on the side, he had a handful of friends — three staff members of St. Mary Hospital, he says, as well as a family member and a close friend — to whom he would give or sell bags of both kief and buds. Paul vehemently denies he ever sold pot to patients.

Mostly, he enjoyed the process.

“I just loved the plants. I loved the relationship,” he says. “I swear to God, I named each of the plants. It’s almost like a bonsai sort of concept.”

For all the enjoyment Paul got out of growing marijuana, Jayne didn’t get better. She ate the edibles, and she even stopped taking Cymbalta and one of the opioids, Paul says. But her body continued to deteriorate. She still suffered from depression. And it was soon clear just how much her depression had advanced.

On a Monday in September 2012, Paul noticed, around midday, that he hadn’t received any text messages from Jayne. He’d sent a few to her — How’s your day? What’s for breakfast? — but he didn’t hear back. He called her on his lunch break and in between patients. Nothing. “And I was thinking of closing the office early to come home,” he says, “but I already had done that a couple of times because of problems she had.” So he didn’t.

“When I got home, it was just getting to twilight,” he says. “And I could see that the light was on in our room — and so I felt relieved that she was okay. And so I go in the house and don’t see anyone there. I looked in the bathroom, and I even looked in the bedroom — I didn’t see anybody in there.”

Where is she? he remembers thinking.

That’s when he found her.

In a corner of their bedroom, beside their bed and underneath a pile of sheets, Jayne lay unconscious, unbreathing. Paul opened her eyelids; her pupils were pinpoints. He began performing CPR. “Every emotion, every horror that I could imagine, all went from nothing to a thermonuclear explosion in a moment,” he says. “It’s hard to even remember. But I can remember it. And eventually: breath. As soon as I saw a breath, that’s when I called 911. They gave her some naloxone. She actually came back to consciousness.”

But she’d been in that state for a long time. The damage had been done. She would suffer multiple serious system disorders, multiple organ failures.

Eventually, the trauma from the overdose would be too much for her body to handle. Paul came home on the afternoon of July 13, 2013. She’d died while reading in bed.

Nine months later, on the morning of April 23, 2014, when the cops arrive to serve a search warrant at Paul’s house and kick open the door to his bedroom, they handcuff Paul in the bed where his wife died, haul him to his feet, and escort him downstairs. They bring him to the kitchen while they conduct a search. Paul can hear them escorting his daughter, Victoria, down the stairs from her room on the third floor.

While the Haverford cops on the scene brief the case’s lead investigator on the illicit garden they discovered, another cop stands watch over Victoria in the living room. The main room of the Ezell residence holds couches and a coffee table, bookshelves filled with books — plenty about medicine, but mostly popular nonfiction and fiction. On the sill of a large bay window sits a host of blooming orchids. Other plants are scattered throughout the room.

“Boy,” says the cop, scanning his surroundings. “Your dad sure does love plants.”

Paul sits and waits, thinking about everything that has transpired in the past few years. His mother had died, too, shortly after his wife. And Paul remembered reading somewhere that in the face of trauma, you’re supposed to keep things consistent, stick with your routines. So he continued to eat the same breakfast every day — toast, coffee, mixed fruit — and to leave for work at the same time. He practiced his guitar after dinner every day and went to sleep at the same time. He continued to tend his garden in the basement.

It was just a part of my life, he muses in his head. I should’ve taken it down earlier.

As it turns out, it was his attempt to take it down that landed him in trouble. He has a theory about who tipped off the cops about his grow operation. (Philadelphia magazine decided not to name that person, who didn’t respond to a request for comment.) But that tip wouldn’t have gone anywhere if he hadn’t begun dismantling his operation and throwing twigs and branches into his garbage bins. That’s where cops found their probable cause.

Sitting there, he thinks about that, and admonishes himself silently.

Then he thinks about his daughter in the other room.

They’re gonna let her go, aren’t they?

“And then within an hour, I’m being taken out of the front door in cuffs,” he says. “They’re still taking stuff out of the basement. And I go straight to the Haverford holding cell, where a two-feet-thick door slams shut behind me. There’s total silence for the next six hours, as I contemplate the fact that my life is now never gonna be the same.”

And it really wouldn’t.

According to the lawyer for both Paul and Victoria, she had nothing to do with the grow operation. But she’s living in the home where it’s located, so Haverford cops charge her with the same offenses as Paul — conspiracy to manufacture and distribute, paraphernalia possession, possession of a controlled substance, all the rest of it.

Google “Paul Ezell” and you’ll get a pretty clear idea of what happens next.

Here’s the headline from 6 ABC: “Eye doctor grew marijuana in his Havertown home, police say.”

The Main Line Times decides on “Delaware County eye doctor arrested over Haverford Township marijuana grow house” for its headline.

NBC 10 keeps things declarative: “Drug Raid at Main Line Doctor’s Home.”

The story spreads throughout the internet, on weed-related sites, across social media. The mug shots tell the story as well as any words can: Paul tight-lipped and defeated; Victoria with bed head, eyebrows raised, confused.

Things progress quickly. With no income from treating patients and the mounting criminal defense costs, there’s no way Paul can continue living in the house on Sagamore Road — so he begins fixing it up to sell it.

He’s formally arraigned in July 2014 and goes to pretrial in September. But before the trial, Paul’s lawyers negotiate a plea deal: If Delaware County prosecutors will let Victoria serve a probationary sentence, Paul will plead guilty to a felony — manufacture, delivery, or possession with intent to manufacture or deliver a controlled substance. The deal will have him serve a maximum of 23 months behind bars, in the George W. Hill Correctional Facility in Thornton — a county jail operated by a private prison company, the GEO Group.

And just like that, in January 2015, Paul C. Ezell, MD — an ophthalmologist without so much as a speeding ticket on his record — becomes a convicted felon.

At sentencing, on January 5, 2015, he gives a statement to the court.

“I would just like to say that I accept responsibility for my actions,” he says, wearing the same charcoal gray suit he wore to Jayne’s funeral and the same shoes he wore at their wedding. “I know that the effect that it’s had on innocent people in the medical community and on patients, neighbors and family, my own future, is something that I will always regret.

“But I also understand that the whole point of responsibility is to accept the response,” he continues. “And as such, I respect the judgment of Your Honor and the Court, and that’s all I have to say.”

There’s a lot of support nationwide for expanded marijuana legalization — decriminalization, full legalization, medical use, etc. — but the push toward leniency isn’t unanimous. After Governor Tom Wolf called for Pennsylvania legislators to legalize marijuana in September 2019, House Republicans released a statement calling the idea “irresponsible.”

“We are disappointed and frustrated [that] Governor Wolf would promote recreational use of [a] drug classified as a Schedule I narcotic by the federal government,” the statement reads. “We do not believe easing regulations on illegal drugs is the right move in helping the thousands of Pennsylvanians who are battling drug addiction.”

Pennsylvania House Republicans aren’t alone.

In March, I contact Scott Chipman, vice president of Americans Against Legalizing Marijuana — a prominent anti-legalization group based in California. I ask whether Chipman feels that someone with Paul’s background — and a story like his, that involves growing pot ostensibly to treat a loved one’s chronic physical pain — deserves any leniency. Maybe a pardon, which is ultimately what Paul is after.

Chipman isn’t sympathetic.

“No drug dealer should get a pardon,” he says, seizing on the facts that police found 28 plants in Paul’s basement and that he admitted distributing marijuana to friends. “There are other ways to show leniency for first-time offenders, but a pardon would undermine the justice system.

“We are not properly messaging to our young people about the dangers of this addictive drug, which is commonly linked to paranoia, depression, suicidality, psychosis and even schizophrenia,” Chipman continues. “The brain is developing until the age of 25, and use during brain development can have lifelong consequences. We need to send the proper message to youth, other drug dealers, and potential drug dealers that they will be arrested and prosecuted. Marijuana drug dealers should not get an exemption.”

And because Paul’s aware that such sentiment exists, he says he has avoided googling himself or looking for anything about the case on social media. If he did, he might find that people are more supportive than he imagines. A post that ran on CBS Philly’s Facebook page the day of his arrest generated 71 comments from readers.

One commenter wrote, “Just make it legal already!!!!”

Another commenter made a suggestion: “Its Weed go after the [Heroin] Dealers leave the guy alone.”

And still another summarized the crowd’s overall opinion: “And not a feck was given.”

Virtually all of the comments show support for Paul rather than condemnation — a surprise for just about any Facebook post, let alone one about a disgraced doctor.

And the Facebook pundits aren’t alone.

When I tell Pennsylvania’s lieutenant governor, John Fetterman, about Paul’s case — and the fact that he has served time behind bars for his crimes — he is incensed. “Matt, are you fucking kidding me?” he says. “He got prison for that!? He did? That’s bullshit. That’s outrageous.”

This is not too surprising, considering that Fetterman is widely known for his support of recreational marijuana, but he’s an important figure for another reason: Among Fetterman’s duties in the state’s executive branch is overseeing applications for pardons. “That guy needs to apply for a pardon, like, yesterday,” he says. “That’s just infuriating that he served time for that.”

Pennsylvania State Senator Sharif Street has similar feelings.

Street, a Democrat representing the 3rd District in Philadelphia, is also vice chair of the state’s Democratic Party. He sponsored Senate Bill 350, which would legalize recreational marijuana in Pennsylvania, allow for personal-use home growing, and retroactively seal the records of anyone ever convicted of a marijuana-related crime. He says it’s a law designed for people like Paul. If such legislation had been passed earlier, he suggests, Jayne might have started out medicating with marijuana, which is understood to be far less addictive than opioids.

“In all of the places where we’ve seen recreational marijuana legalization, opioid abuse has gone down,” Street says, referring to a Minnesota Department of Health study that found 63 percent of more than 350 chronic-pain patients self-reported a reduction in or elimination of opioid use after using marijuana for six months.

Paul’s daughter, Victoria — who spent a night or two in jail, lost her nursing license, and had to serve probation because of what her father did — holds no grudges. “I’ve never had any type of ill feeling toward him,” she tells me. “They were just plants … that got created and grew in our basement. I don’t know why that should require anyone to go to prison.”

Paul and Victoria filed pardon applications in early March. They received confirmation of their applications on March 9th. Talking with Paul about his sentence is a little surreal. He doesn’t seem to have minded the six months he spent in prison — he was released in June 2015, his sentence reduced for good behavior — at all.

When Paul says he took “an artistic approach” to growing marijuana, and that he developed “a relationship” with each plant, it’s not just that he felt a kinship with the object; it’s that he developed a kind of rapport with the pursuit itself.

Paul describes himself as a tinkerer, but that’s not quite accurate: He’s obsessive about learning and understanding new things. As we talk about his time behind bars, he shows me his prison journal. It consists of about a hundred pages of blue-lined yellow legal paper, filled from top to bottom and on both sides with a recounting of each day, including what songs and public radio programs he listened to on the tiny radio allotted to him. His prison activities included reading — and taking borderline-compulsive notes on — the New American Bible. He taught himself to play chess. He taught himself the computer programming language C++. He read dozens of books. He even made some friends. He talks warmly about how his fellow inmates took to him, calling him “Doc.”

And he talks about how his prison sentence allowed him to think about what he did — and how he might rebuild his life.

For the time being, he’s working as an office administrator with a chiropractor — someone he deeply respects but whom he’s asked not to identify, to avoid drawing any negative attention to the practice. In his spare time, he’s taken up guitar building and has even sold a few custom models under the name Paul Ezell Guitars. But he really wants to get a pardon for his daughter and have her nursing license restored. He would also like to return to ophthalmology, to get his medical license reinstated so he can practice again.

That’s not completely out of the question. One of the strongest claims against Paul from the get-go came from that anonymous tip. “Through a third-party source it has come to my attention that Dr. Ezell is growing marijuana at his residence and selling it to his patients and other individuals,” said the tipster in a note to the Haverford police department. “Since he is a doctor and places himself in a position of trust, I thought you should be aware of this. I have had direct above-board dealings with him and view him as extremely deceitful, self-serving and a potential threat to the community.”

Did he actually sell to patients?

Delaware County Assistant District Attorney Diane Edbril won’t comment about Paul’s case, citing his active pardon application. I ask Jules Epstein, a Temple University law professor and Pennsylvania criminal law expert, if the length of time Paul served in prison tells us anything about whether he was dealing. “It is impossible to tell from the public information whether there was actually proof of selling to patients, and if there was selling to a patient, whether it was based on a good-faith medical basis,” Epstein says.

But Arthur Donato, who represented Paul in his criminal proceeding, says that he didn’t believe the DA’s office was able to corroborate the claim that Paul sold weed to patients. That prosecutors pushed Paul to plead to a felony still strikes Donato as excessive. “I don’t really know why they were taking such a hard line on it,” he says. “What they would probably say here is, ‘The reason we were is because that’s … the laws that existed in Pennsylvania and we’re sworn to uphold the law as it exists, not as we’d like it to be.’”

Paul denies such sales vehemently. “How would that even work?” he asks, incredulous. “Would you put it on a sign out front? Would you be talking with your patients and just say, ‘Oh, by the way, I can get a bag in addition to Lasik?’ Come on. Just think about this. … Of course I wasn’t doing that.”

And if he wasn’t — and if he can get a pardon — it’s feasible both he and Victoria could get their medical licenses back.

Brian E. Quinn is a Philadelphia lawyer who advocates for clients who have lost their professional licenses. If Fetterman, the state’s lieutenant governor, thinks Paul’s got a shot at a pardon, Quinn says, he might someday practice medicine again: “I mean, if they, in fact, pardon him, then, you know, theoretically the medical licensing board can’t deny his reinstatement based on a pardoned drug conviction.”

It could refuse reinstatement based on drug abuse, though — which Paul denies.

“So if this scenario is that there’s no allegations he ever abused anything and it’s just that he was growing pot for his dying wife, then I would think … he would have a lot of sympathy on his side,” Quinn says.

Paul’s hoping as much.

When he told a judge on January 5, 2015, that he accepted responsibility for his actions, there was a purposeful hedge built into the statement. He accepted responsibility. But he didn’t agree that it was wrong — that it was immoral.

“I would challenge anyone to tell me how another course would have been a moral course,” he says of growing pot for Jayne. “Many people who consider themselves moral — they know what’s right or wrong, but they don’t know why. Moral intelligence is understanding why something is right and why something is wrong.”

In Paul’s opinion, he did nothing wrong. And he knows why what he did was right.

“I did what I did to help my wife — to help an addict,” he says. And it hurt no one, he goes on, “except the community that I hurt because I lost my profession and obviously myself, but no one else.

“I took that Hippocratic oath, and I meant it,” he continues. “First, do no harm. The first line of the Hippocratic oath. So when I took that step” — of growing pot for Jayne — “I’d say that was my mission. And I don’t see how that’s been proven wrong.

“So what am I sorry for?” he asks, sitting on the tan couch in his Upper Darby rowhouse. “I’m sorry for the fact that in the course of me being arrested and all the consequences that have happened, many people’s lives have been disrupted. … Everyone’s actions are just like a pebble hitting a pond. So there’s these immediate consequences. Then there’s the ripples of continuing unintended consequences that go out in the world. And I disrupted that, but only because I didn’t go about it the right way and I didn’t stop when I should have — not because there was something inherently corrupt about the action.

“Although I would like to see if I’m wrong,” he says. “Because then I could learn something.”

Published as “The Eye Doctor and the Grow House” in the June/July 2020 issue of Philadelphia magazine.