Inside Nikil Saval’s Progressive, Virtual Campaign For State Senate

Saval, a former magazine editor and founding member of Reclaim Philadelphia, was planning to take on 12-year incumbent Larry Farnese with an army of door-knockers. Now he's doing it over Zoom.

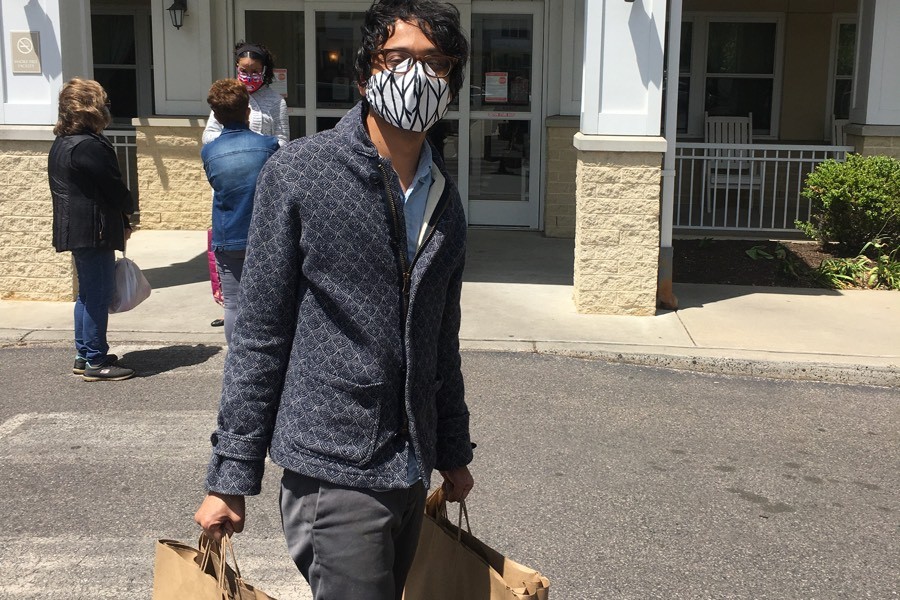

Nikil Saval dropping off Thai food at the St. Monica’s nursing home in South Philly. Photo courtesy of Nikil Saval campaign.

Not long ago, Nikil Saval, a candidate for Pennsylvania’s first state Senate district, was handing out food for the hungry at the Southeast Asian Mutual Assistance Association Coalition in South Philly. It wasn’t entirely clear, even to Saval, if what he was doing was part of the campaign, or if it was simply him — the citizen, the organizer, the co-founder of progressive grassroots organization Reclaim Philadelphia — doing what he has always done: Volunteering.

At one point that day, Saval ran into state Senator Larry Farnese, his opponent in the Democratic primary. “We both had just coincidentally shown up the same day,” Saval told me recently. The two made small talk, Farnese delivered food for 20 minutes, and then, after a strategic and efficient photo-op, he was gone. “I stayed two hours,” Saval said. This might have been a slightly pointed remark, but what Saval really meant was this: He hadn’t even thought to bring a photographer. “I guess I’m uncomfortable with it,” he said — the “it” being showmanship and grandstanding, which is to say, campaigning.

Saval’s ambivalence is in part due to novelty. At 37, this is his first campaign, unless you count the junior varsity election that saw him become leader of the city’s second ward in 2018. And even that election Saval backed his way into: He’d led an effort to recruit a bunch of Reclaim members to run for committee person in the ward, as part of the organization’s strategy to infuse staid Philly politics with progressivism from the ground up; when the Reclaim contingent won, it was decided that Saval — who initially didn’t have designs on anything beyond being a committee person like everyone else — should run as ward leader. Then, last year, when Reclaim — after a series of unexpected and status-quo-shattering victories that saw them help elect District Attorney Larry Krasner, City Councilmember Kendra Brooks and State Representative Elizabeth Fiedler — decided its next target would be the first Senate district, the group once more converged on the idea of Saval as the candidate. “I wasn’t horrified by it,” he says. “In fact, I was fairly excited.”

About that district: Even the most skilled Philly political satirist couldn’t dream up something as rich as the chain link of corruption that encircles the real-life First District. This was the territory of Buddy Cianfrani from 1967 to 1977 — until he was indicted (and convicted). Then it was the fiefdom of Vince Fumo from 1978 to 2008 — until he was indicted (and convicted). Then, in 2008, Local 98 union boss Johnny Doc tried to make it his fiefdom, until he was … scratch that, Doc wasn’t indicted until 2019. But his opponent in that 2008 race was Larry Farnese, and, well, he was also indicted, for allegedly bribing his way to victory in an election for ward leader. Unlike his predecessors in Fumo and Cianfrani, Farnese at least managed to beat the charges.

Saval, whose pre-politics profession was as a writer and editor of a literary magazine, promises to be a different sort of candidate. For starters, he’s been known to pledge at campaign events that, if elected, he’ll be the first representative of the district in decades not to be federally indicted. That would be ground-breaking in its own right; Saval would also be the first South Asian state elected official in the history of Pennsylvania.

For trend watchers of Philly politics, the race is also a sort of bellwether for the Reclaim political machine. It has accumulated some impressive victories, but it has yet to unset a powerful incumbent on the order of Farnese. Reclaim’s tried-and-true playbook emphasized grassroots organizing and door-to-door canvassing. The COVID-19 pandemic has ripped up the pages, though, and in doing so, it may have stolen away Saval’s best shot at victory.

UNDETERRED, the Saval campaign has taken to meeting people however possible. Last Monday night, that meant a 90-person Zoom “town hall” to discuss one of the campaign’s signature policies: a so-called Green New Deal for housing, which would include things like constructing new public housing projects and retrofitting homes across the city to become more energy efficient. Saval, who describes his own campaign as “unabashedly intellectual,” appeared on screen in a slim blue button-up shirt, large-framed glasses, and with an earth-spanning bookshelf behind him.

The event was billed as a conversation between two professors, and Saval, despite this being his campaign, spent most of the time listening, punctuating his silence every so often with a question to the presenters. Eventually, Saval’s deference became something of a running joke. At one point, one of the presenters, a Penn sociology professor named Daniel Aldana Cohen, said, “Nikil has interesting ideas that I wish — I would like him to share — about how to cancel rent.” Saval, smiling sheepishly, replied, “Yes, I suppose I could, since it’s been broached,” before launching into one of the few extemporaneous policy proposals he gave that evening.

Not every event is like this, insists Amanda Mcillmurray, Saval’s campaign manager. Still, it’s indicative of who Saval is. “He’s just incredibly humble,” says Mcillmurray. “He talks in ‘we,’ instead of claiming ownership.” She’s had to nudge him, telling him that it’s okay to take credit for his accomplishments.

On the face of things, Farnese and Saval aren’t so different. Farnese’s platform covers the same themes as Saval’s: an emphasis on climate change, criminal justice reform, education. Farnese likes to say that he was progressive before it was cool. But if Farnese is pointed in the general right direction, Saval believes he hasn’t done nearly enough to actually earn the progressive moniker. “We thought that he had been here for 12 years and was not an especially progressive person,” Saval says, before adding that the P-word has been “rendered meaningless in the course of this race.”

The hill that Saval will have to climb in differentiating himself from Farnese has been made considerably steeper by the pandemic. Normally, he and his small army of volunteers could convince voters what he stood for the best way they knew how: By standing right in front of them. Suddenly, what the campaign thought of as its unassailable organizational advantage disappeared. It was a gut punch at first. “We felt fairly disconcerted, because we all come out of a face-to-face organizing tradition,” says Saval. But the campaign pivoted quickly, trading volunteer door-knocking for volunteer phone-dialing, and Mcillmurray says the campaign has now attempted 145,000 phone calls to people in the district.

On Election Day, more than 80 percent of polling places will be closed, and mail-in ballots, which have already been requested by 200,000 people citywide (outpacing the entire turnout of the 2012 primary) figure to be the critical variable. In the First District alone, more than 55,000 people have requested mail-in ballots. The fog surrounding vote-by-mail, and who it might benefit, means that no political pundit really wants to partake in the usual horse-race prediction game. One of them, Neil Oxman, is at least willing to walk through the tale of the tape, though. “The Reclaim people have a hardcore group and are committed,” he says. “But then Farnese has more name recognition and some TV advertisements. It’s a pick-em.” Mustafa Rashed, another political consultant, who has given money to the Farnese campaign, suggests all incumbents will benefit from the shutdown. Voters, he says, “will just go with person they know about and are most familiar with.”

Saval might never have the visibility advantage attached to incumbency, but his profile is incontestably growing. In mid-May, he was endorsed by Bernie Sanders, which had some symbolism of its own: Saval’s first political volunteering experience came with the Sanders campaign in 2016. A few days ago, Saval also received a noteworthy, if somewhat fraught, endorsement from Local 98, which wrote the campaign a check for $25,000. (Saval says he didn’t meet with Johnny Doc at any point during the endorsement process, and had no qualms taking the money: “This is union members’ dues, and I’m a labor candidate.”)

As the primary enters its final stretch, Saval has started to go on the offensive. He recently sent out mail to voters that highlights Farnese’s indictment (while leaving aside the fact that he was acquitted). And he’s sought to lay claim to his own progressive bona fides, at Farnese’s expense.

“We’ve already set the terms of this election,” says Saval. “Senator Farnese is sending out emails saying he is the leader on the Green New Deal. He’s on TV saying he’s the strongest advocate for single-payer healthcare. All of this is not true, actually. But he feels this is what he has to say. There is no Pennsylvania Green New Deal. That’s a lie. He made that up.” (Mark Nevins, a Farnese campaign strategist, disputes this. “There simply is no significant difference between Senator Farnese and Nikil on the issues. The only difference between them is that Senator Farnese has actually delivered results on these issues,” he wrote in an email.)

But to Saval, at any rate, what he perceives as Farnese’s leftward lurch is essentially a proof of concept for his entire campaign. “This,” Saval says, “is what happens when you take a primary challenge very seriously.”

This story has been updated to correct the number of voter outreach attempts by the Saval campaign.