Eastern State Showcases Work of Incarcerated Filmmakers in “Hidden Lives Illuminated”

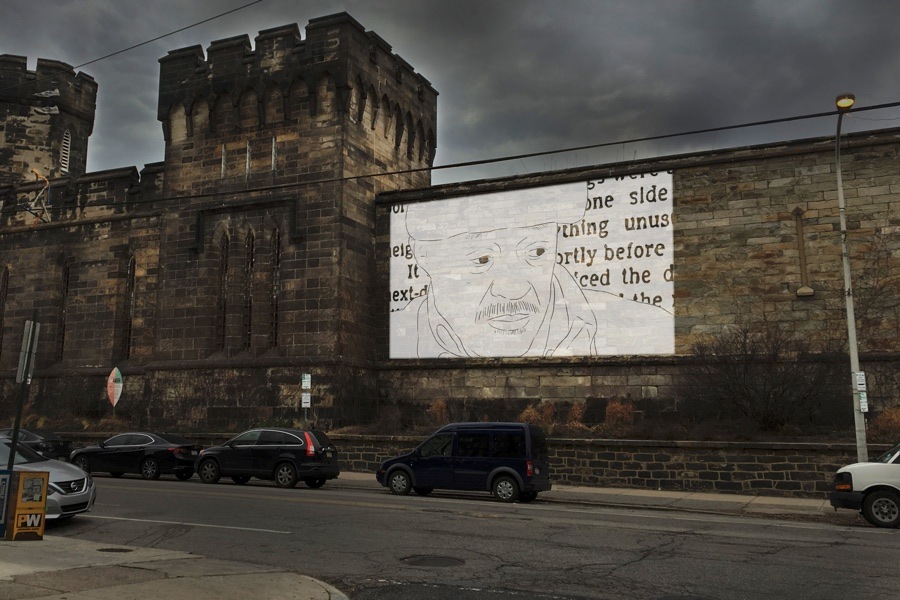

Through September 12th, the former penitentiary and museum is projecting 20 animated short films about life in prison — each written and produced by a current inmate — onto its outside walls.

Hidden Lives Illuminated runs through September 12th. Photo courtesy Eastern State Penitentiary.

When Sean Kelley, director of interpretation at Eastern State Penitentiary, stood before inmates at the Chester State Correctional Institution a year ago to ask if they wanted to learn animation and make films about their experiences, the reaction was tepid. “The literal response at moment was silence,” recalls Kelley.

This could have been a problem. Kelley and other staff from Eastern State had a grand vision: a filmmaking project, “Hidden Lives Illuminated,” that would allow incarcerated people to make short animated films about their experience for the public. The ultimate idea was to broadcast the films onto the facade of Eastern State Penitentiary, turning one prison’s walls into doors to another. Kelley and his team already had a $297,000 grant from the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage. But it would have been worthless without filmmakers.

Eventually, removed from the prison’s public forum, 100 volunteers came forward, from which the state Department of Corrections selected 20. Over the next year, staff from Eastern State Penitentiary came into the Chester prison and the Riverside Correctional Facility for women every week to work on scripts, drawings, and recordings for the project. Last week, the first of those films, on the theme of “the view inside,” began to air outside at Eastern State Penitentiary. The free, two-minute screenings — each one narrated by the filmmakers themselves — will continue to rotate weekly until September 12th. (You can view the full schedule here.)

The completed films each had their moments of angst and transformation. Kelley’s initial idea was to ask each of the filmmakers to produce a meditation on the theme of routine. “Most people said that’s last thing they want to talk about,” he says. “So we let them explore their themes.”

This produced its own set of challenges. Some filmmakers — many of whom are serving decades-long sentences — wanted to make movies attacking the Department of Corrections over what they felt was unjust treatment; one nearly quit the project over the issue. But this wasn’t simply carte blanche for the inmates, Kelley emphasizes; there were other imperatives. “We’re treating them the way we’d treat any artist in partnership for creating programming for the general public,” he says.

The logistics presented other obstacles, such as making films in a prison in which no cameras or cell phones are allowed. No exceptions were made for Erika Tsuchiya-Bergere and William Wallace III, the two artists hired to shepherd the filmmaking process. When they wanted to bring an iPad into the prison to help capture the first stirrings of animation, someone had to remove its hardware so that it couldn’t connect to WiFi. The ban on computers meant the editing process had to happen outside the prison. (Tsuchiya-Bergere and Walllace would make rough cuts themselves, then bring in drafts for the filmmakers to critique and modify.)

The finished products leave little trace of piecemeal production. But for all the focus on animation, it’s actually the audio that’s most arresting. The scripts were all recorded by the filmmakers inside the prison, which produces a certain echo — the sound of voices bouncing off cinderblock walls.

In one film, “Freedom,” one of the few to keep to the original plan of discussing routine, the narrator speaks of throwing his life away 20 years ago. “I wake up every day to be counted; however, my routine is to avoid people and be as unnoticed as possible. The rest of my day is like I sleepwalk. No matter how much I try, the front doors to freedom are out of reach.” In another film, a father weighs himself as a role model: “How can I teach my children to be leaders when I blindly followed the masses?”

A feeling of catharsis seems to emanate from these films. But for all the links between prison and rehabilitation, that wasn’t what this project was ever about. “It’s not our job to rehabilitate people,” says Kelley. “We do, however, think people in prison have a really important perspective worth listening to.”

“Hidden Lives Illuminated” broadcasts films hourly from 7 p.m. to 9 p.m. The program culminates on September 12th with a complete screening of all 19 films, along with a documentary about the filmmaking process. For more information, go here.