Tre Johnson writes at Dearth of a Nation.

Muhammad Ali Is Dead; His Biggest Fight Continues

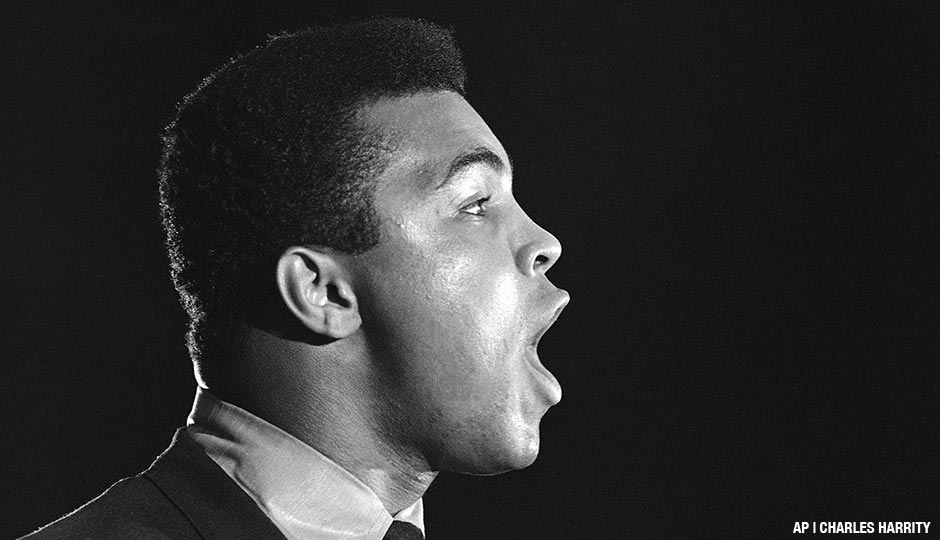

Muhammad Ali speaks at an anti-war rally at the University of Chicago on May 11, 1967.

On June 7th, four days after Muhammad Ali passed, I was on Facebook when I saw it: a meme posing as a promotional ad for a fictional fight in heaven (“Holy Fighting Championship”) between recently deceased MMA fighter Kimbo Slice and American icon Muhammad Ali atop a set of heavenly clouds. Billed as “Rumble at the Pearly Gates,” it was your typical (knee-)jerk internet hot-take for a laugh; the two prized fighters preparing to duke it out in the type of “What if?” motif usually reserved for dead hours on sports talk radio and Marvel Comics.

Both men were framed in a heavenly glow: Ali with his gloved fists raised and at the ready, and Slice with his long, languid limbs hanging like loose wires at his side; heaven’s pearly gates cast open wide behind them.

But squarely in the middle of these two black fighters was a conspicuous inclusion: The promo ad also announces that this fabled match would be refereed by Harambe, the Cincinnati Zoo gorilla recently shot and killed after becoming inadvertently involved in an accident with a black child.

My typical instinct to battle and rage on Facebook was replaced with the dismal dismay of an all-too-real truth; that even when society touts black icons as having “risen above race,” there will never be a missed opportunity to reduce us to primates. Even in death, Muhammad Ali, who was laid to rest Friday after losing what felt like a century-long fight to Parkinson’s disease, remained in a battle over how society sees black people.

The meme is a reminder, too, that the man who was eventually touted as a humanitarian whose impact had “transcended race” had never really escaped the vortex into which America tosses the black image. At the end of the day, when you die, they’ll raise you up to the skies and have you battle another black man in the afterlife while overseen by a monkey.

This situation would have undoubtedly been familiar to Ali, a man whose most oft-cited phrase — Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee — could have as easily been about his verbal jabs as his prowess as a fighter. Ali was like a human Internet before its time, a dynamo of quotes, contradictions and controversies, a Twitter-like composition of 140 characters: He was a boxer, a rapper, a conscientious objector, a father, a husband, a Muslim, a leader, a disciple, a humanitarian…

And fiercely smart, too. In what would spark a running feud until Philly fighter Joe Frazier’s death, on the eve of their famous fight, “The Thrilla in Manilla,” Ali famously referred to battling Joe Frazier in one of his trademark rhymes: “It will be a killa and a thrilla and a chilla when I get the Gorilla in Manila …”.

That term, “gorilla,” would haunt both men, Frazier in particular, for years afterward. By the violent, turbulent 1960s, associating blacks and monkeys had become as commonplace as the word “nigger”; debasements meant to render blacks powerless. It was likely true that the darker-skinned, rugged-looking Frazier felt this slight more deeply than the lighter-skinned, model-like Ali, and Ali, a masterful manipulator of man and media, likely knew what it meant to Frazier’s psyche as a pre-emptive — and arguably cheap — shot before the bout.

And why wouldn’t Ali recognize this? Outside the ring, Ali waged a bigger battle: using his omnipresence to wage guerilla warfare against racial injustice in the United States, using the media as a pulpit/punching bag to take on white American hypocrisy. It’s what lifted him to modern-day folk hero status — an invincible black Superman who seemed possessed of unquenchable desire to redress truth, justice and an American Way that included black people.

My mother, a black child of the 1960s, talked about memories of listening to his fights on the radio in Trenton, and it’s easy to imagine Ali’s every literal and rhetorical fight being a viral sensation; blacks across the country listening, hushed and huddled over radios in the back kitchens of homes and restaurants, boxcars of trains, hunched over stoops shining shoes listening to an Ali-centered broadcast as he battled everything from George to injustice.

In those honest moments of racial clarity and disdain, black and white families must have felt that they were hearing “War of the Worlds” all over again, this time playing out over racial lines.

It’s with this dynamic that I think of Ali delivering his most poignant rap/political quote, conjoining the state of Black America and the Vietnam War at a time when the country was calling all to enlist to serve and he objected: “On the war in Vietnam, I sing this song / I ain’t got no quarrel with the Vietcong.” Later, a more detailed statement captured what many blacks felt: “The real enemy of my people is here. … If I thought the war was going to bring freedom and equality to 22 million of my people … I’d join tomorrow. … So I’ll go to jail, so what? We’ve been in jail for 400 years.”

It can be hard to appreciate this version of Ali when many of the in memoriam takes show him in his latter years, a lovable, bear-like warrior-man, mute aside from the constantly talking glint in his eyes, tamed by disease. But make no mistake: The fire in Ali that inspired blacks decades ago still rages on. It’s why his legacy lives on differently for blacks. We know the guerilla war; we carry it on our chests with a war-cry: rumble, young (wo)man, rumble.