The Philly Chef on a Mission to Share the Wonders of Haitian Cuisine

Chris Paul’s Lakay pop-up is a deeply personal culinary introspection of his own Haitian heritage.

Many first-generation Americans go through what Chris Paul went through deep into his culinary career. I know this from personal experience, but also because I’ve met and worked with so many people — so many chefs — who went through a similar sort of self-analysis: An audit of personal connection, to the restaurants they own or work in, or to the food they make, or simply, to their own heritage. It’s an often complicated and fraught connection, especially in a food community that can so often pit cultural preservation and assimilation against each other. In a restaurant scene like Philly’s (that historically and disproportionately overvalues Eurocentric dining standards), it can mean abandoning one for the other — assimilating to a culture that isn’t your own for the sake of personal gain and success.

Paul’s audit started with soup joumou, Haitian pumpkin soup. “It was a delicacy that the French always had the slaves prepare but were never able to eat,” he says. “So once we got our independence in 1804, we’d eat it on January 1st every year. It’s something that, if you’re Haitian, everyone knows about, even if you’re first-generation. If you don’t make it yourself, you’ll go to someone’s house and they’ll make it. It’s a group effort.” For years, the Caribbean shops around town helped scratch his itch for Haitian cuisine. “You have your standard Jamaican take-out, where you get a ton of rice and some chicken. It’s good, it’s flavorful. But what they’re making in those shops is a means to an end.” It’s a small taste of home, he means. He wanted to go deeper.

So he started making the soup himself. He is a professional chef after all.

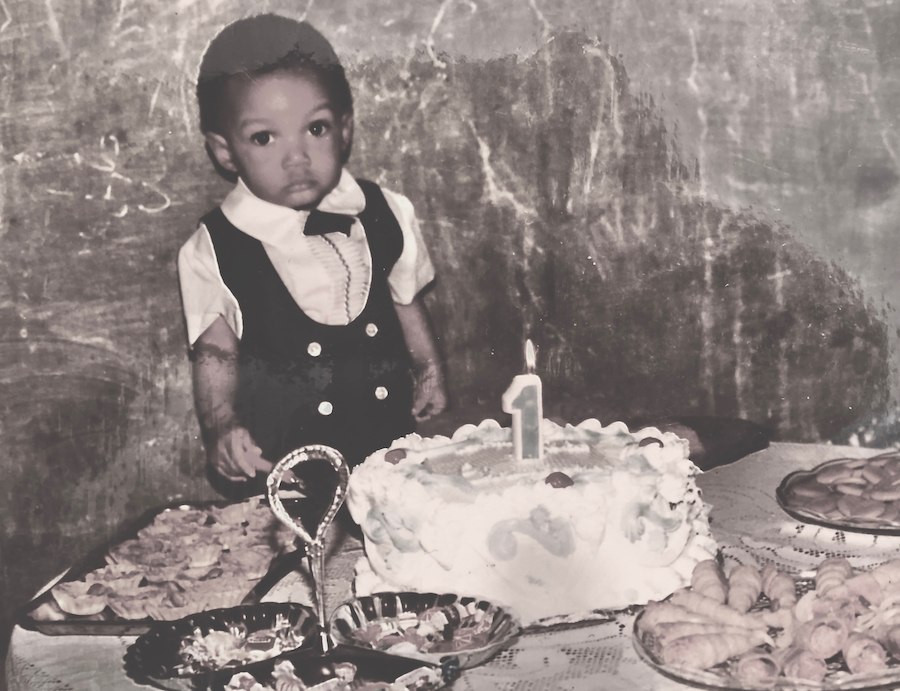

“Right around when I was around 11 years old, I grew interested in cooking, ironically, from my distaste of Haitian food — or, not for lack of a better word, my ignorance of what it was,” Paul tells me in an interview. He was born in Brooklyn, but he lived in Haiti till he was about 10 years old, before moving to Philly. He says that he was born into a proud Haitian household. That there’s not a year that goes by without a trip back home.

“But growing up in Philly, we just kind of ate rice and beans and all of the basic things,” he says. “Around junior high, I was like, ‘Hey, I’m kind of tired of this. Let me try to make some of my own stuff.’” This pushed him down a culinary career path in Philly that included culinary school, stints at Starr Restaurants and Garces Group, a couple catering gigs. He even opened a short-lived healthy fast-casual restaurant in University City called Herban. “I was cooking everyone else’s food. French-fusion for the most part. And what I realized, a few years ago, was that I missed [Haitian food], and that I didn’t know where to get it. I fell back in love with my cuisine.”

There’s a period of rediscovery — a return to roots — that’s a very important and pivotal part of the first-generation American experience, especially among chefs. We saw it with Lou Boquila, who cooked French and Mediterranean food at Audrey Claire’s restaurants in Rittenhouse for two decades before he opened Perla, a Filipino BYOB he named after his late mother. At Perla, and at his Fishtown restaurant Sarvida, he tries to recreate the tastes, smells, and textures of his childhood. His menus aren’t hyper-traditional, per se, just personal. Food memories put to plate in whatever way he sees fit.

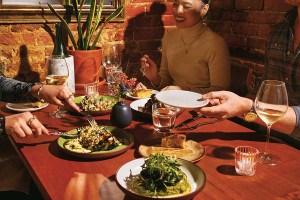

Legim ak Bef (beef veggie stew) diri nasyonal (rice and beans) gratin makawoni (bake macaroni and cheese). Blanc Manje dessert (condensed sweetened milk fruit cocktail), soursop punch | Photo provided

Same goes for Paul, who launched a pop-up called Lakay. “The word ‘lakay’ in Haitian Creole means ‘home’” he says. He’s cooking the food he grew up eating, dishes he misses, or as he puts it, “feels for.” Which could mean cornmeal porridges called mayi moulen, fried whole fish, baked mac and cheese with ground beef. It could mean Haitain limeade mixed with star anise extract called sitwonad, a soursop punch called kowosol. On his upcoming menu, it means lalo, a dish he’s especially excited about that features stewed jute leaves mixed with crab.

“I would say my food is definitely traditional, but not modern. As far as plating, I obviously want to make things look appealing, but I really wanted to step away from the purées and the microgreens. Because even now, there are a lot of cool Haitian chefs I’ve seen post dishes on social media, and then they’ll just sprinkle a bunch of micro-basil on top. Like, what is that? It’s not true. If you give that to my grandma, she’d say, ‘Why is that on there?’ I try to keep it very traditional, but definitely from a personal standpoint.”

It’s all a little tricky, though, given that Haitian cuisine hasn’t yet hit mainstream American palates. Paul says 50 percent of his customer base is of Haitian descent. The other 50 percent requires a bit of education — something he’s participating in himself. “I went to the coastal cities three years ago — they were grilling octopus. It’s a small country, but at one end they’re eating ceviche and then you get to the city, and no one eats anything raw. I kept realizing that our food is immensely diverse.”

So he does the research, he makes calls, he reads cookbooks and bounces ideas off his brother (who’s also a chef). “A lot of times, as I do these pop-ups, it’s stuff I’ve never made before. After cooking for so long, I would say that I’m pretty good at it now, so a lot of things aren’t challenging. It’s a process. But to be making something that I know what it tastes like and what it looks like, but I’ve never made it? It’s a challenging, curious thing.”

COVID-19, in some ways, helped Paul spread the gospel of Haitian cuisine. Coronavirus shut kitchens down. It literally closed doors. But it also opened others: The pandemic spurred a new wave of pop-up kitchens and collaboration among chefs in this city. Cadence in Kensington hosted a Lakay pop-up. So did Herman’s Coffee Shop in Pennsport. Saté Kampar has a long-term residency at the Goat in Rittenhouse. Next week, Hardena is doing one of its gorgeous #NOTPIZZA boxes with Noord in South Philly. Bok Bar is hosting pop-up dinners for the entirety of its 2020 season. El Compadre, South Philly Barbacoa’s sister restaurant, is now, as the Inquirer put it, “an ambitious community kitchen where a daily-changing roster of guest chefs cooks 1,000 free meals a week for those in need.” And South Philly Barbacoa, itself, will be hosting pop-ups all summer long — Lakay included.

Paul says he’ll be taking over their Instagram to provide their 29,000 followers, and his customer base, with some historical context. “When I started rediscovering my food, I also started rediscovering my history,” he says. “I’m learning about the country. I’m reading all of these books, and I started following Haitian people on Instagram. I’ve been learning a lot from them. And I, myself, am going to start posting more as well, starting with my pop-up at Barbacoa. I’ll throw some historical pieces in there and start pointing out our history. It’s a very unique history. It’s the only successful slave revolution, to start. There’s only been one country that’s won in the history of mankind. And obviously, we’re getting all this bad press because there’s corruption in Haiti — but from my end, if I’m going to promote the same negative thing, then what’s the point of doing this? There has to be some positivity. Someone needs to shed light on why we are where we are.”

Chris Paul’s Lakay pop-up will be operating out of South Philly Barbacoa next week (August 11th to the 13th). Place your order by DMing him on Instagram or texting 215-200-9377. Check out the menu here:

View this post on Instagram