The Oral History of the Cheesesteak

Everything you need to know about the sandwich we can't live wit'out.

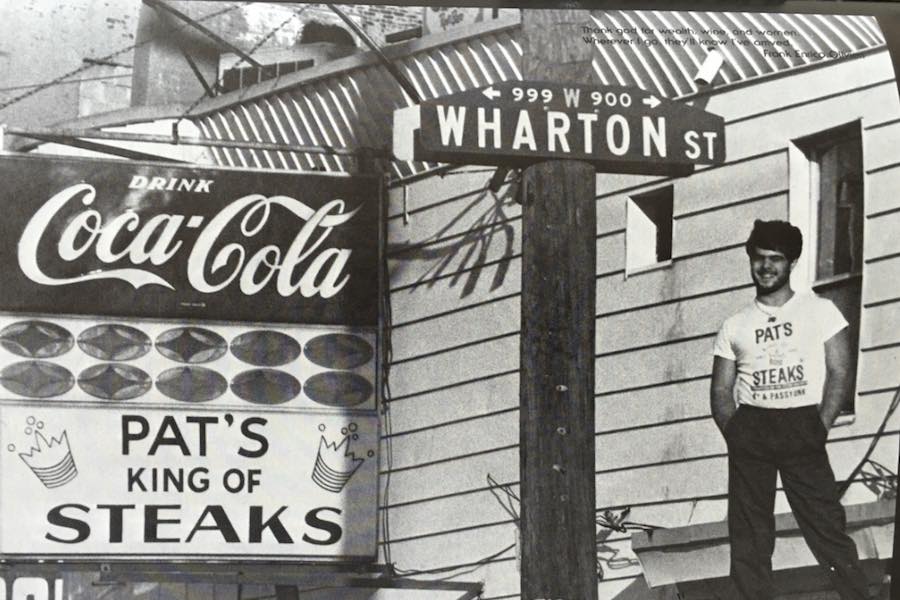

Frank Olivieri — the current operator of Pat’s Steaks in Philadelphia — standing on a roof at the cheesesteak shop in 1982. (Photo courtesy Frank Olivieri)

National Cheesesteak Day may be on March 24th. But this is Philadelphia, where every day is cheesesteak day. That being said, we thought this would be a good time to take a look back at Philly Mag’s massive undertaking from 2008: The Oral History of the Cheesesteak.

You may think you know who has the best cheesesteak. But do you know the real story about the history of the cheesesteak? Our account of Philly’s cheesesteak history delved deep into the origins of and the opinions surrounding the sandwich.

It should be noted that some of the people we interviewed back then are no longer with us, a fact that we’re just going to assume has nothing to do with the health impact of a great cheesesteak. Additionally, some sources have moved on to new jobs. But in the interest of historical integrity, we left the original content intact.

And now, without further ado…

The Oral History of the Cheesesteak

Of all of the contributions Philadelphia has given the world (like, say, democracy), none has become more identified with our city than the tasty concoction Pat Olivieri invented back in 1930. The cheesesteak has evolved into our signature icon, the most Philly of Philly symbols, recognized (and eaten) around the world. Here, an oral history of the sandwich we can’t live wit’out.

Frank Olivieri, owner, Pat’s King of Steaks: My great-uncle, Pat — that was my grandfather’s older brother — he had a hot-dog stand he opened around 1930. The neighborhood was always busy, with one of the country’s first open-air markets — that’s the Italian Market — a block away.

Celeste Morello, South Philadelphia historian and author of Philadelphia’s Italian Foods: By the time Pat’s came along, the whole area was a largely Italian neighborhood.

Frank Olivieri: The workers would line up. He would sell them hot dogs off his little cart. And then one day Pat wanted something different for lunch; he was tired of the hot dogs. So he asked my grandfather to go down to the butcher and pick up some scraps of meat. When my grandfather came back, Pat cooked it up on a hot dog roll. There was a cab driver there who saw the sandwich and said, “Wow, that looks really great. Make me one.” Pat told him he only had enough beef for one sandwich, so they split it. The cab driver said, “That’s terrific. You should stop selling hot dogs and sell these things.” And that was the invention of the steak sandwich.

Celeste Morello: Actually, back in the 19th century, there were cookbooks that included recipes for the steak sandwich. It was called the “beefsteak sandwich.” But the Olivieris in the 1930s did it a little bit differently. Different bread. Different seasonings.

Frank Olivieri: Across from Pat’s hot-dog cart, a man named Joe Butch had a building. The second floor was a kitchen, and downstairs there was a tavern. When it started getting cold, Joe Butch comes to Pat and says, “Listen, winter is coming. Why don’t you just make your sandwiches in here?” Eventually, more people were eating than drinking, so the guys who owned the taproom decided to cut a hole in the wall and start serving the sandwiches through it. Eventually, Pat took over the entire building.

Bill Proetto, owner, Jim’s Steaks: You had Pat’s in South Philly, and then Jim’s in West Philly in 1939, at 62nd and Noble. The house on the corner was Jim’s, and he used to sit in the front window. Guys would be standing on the corner. So Jim started to sell coffee out the window. Eventually, he got the idea to do the steak sandwiches.

Frank Olivieri: The original Jim’s is miles away from Pat’s, so he didn’t affect us much. And Pat started making his way into using the pictures of celebrities to heighten the business, and people would come from all over to see them. Pat would go to theaters where celebrities would be — movie premieres, that kind of thing — and bring steaks to give to them. He met Humphrey Bogart one time, and Uncle Pat pulled out his .38-caliber revolver and asked Bogey to hold the gun on him while he held his hands up. Uncle Pat was crazy.

Bill Proetto: Jim’s never really went in for the celebrity photographs early on. That was not really a focus. Jim’s had and has better-quality meat. The cheese didn’t come around until the ’50s or so.

Frank Olivieri: The cheese really came up in the ’40s out at the Pat’s on Ridge Avenue. The first cheese was a provolone cheese. We had a manager named Joe Lorenza, or Cocky Joe. He was always drunk, completely inebriated. A waste of our time. But he was the first person to put cheese on the sandwich.

Celeste Morello: There seems to be no indication of cheese on the sandwich before Pat’s did so, thus inventing the cheesesteak.

Frank Olivieri: By the early ’60s, Uncle Pat had moved out to Los Angeles. My father, my grandfather and my cousin Herb — Pat’s son — were operating the business. Around the time that Geno’s came along, that was 1966, my grandfather and father bought this location [at 9th and Passyunk] from Pat. So then it really became a Pat’s/Geno’s thing.

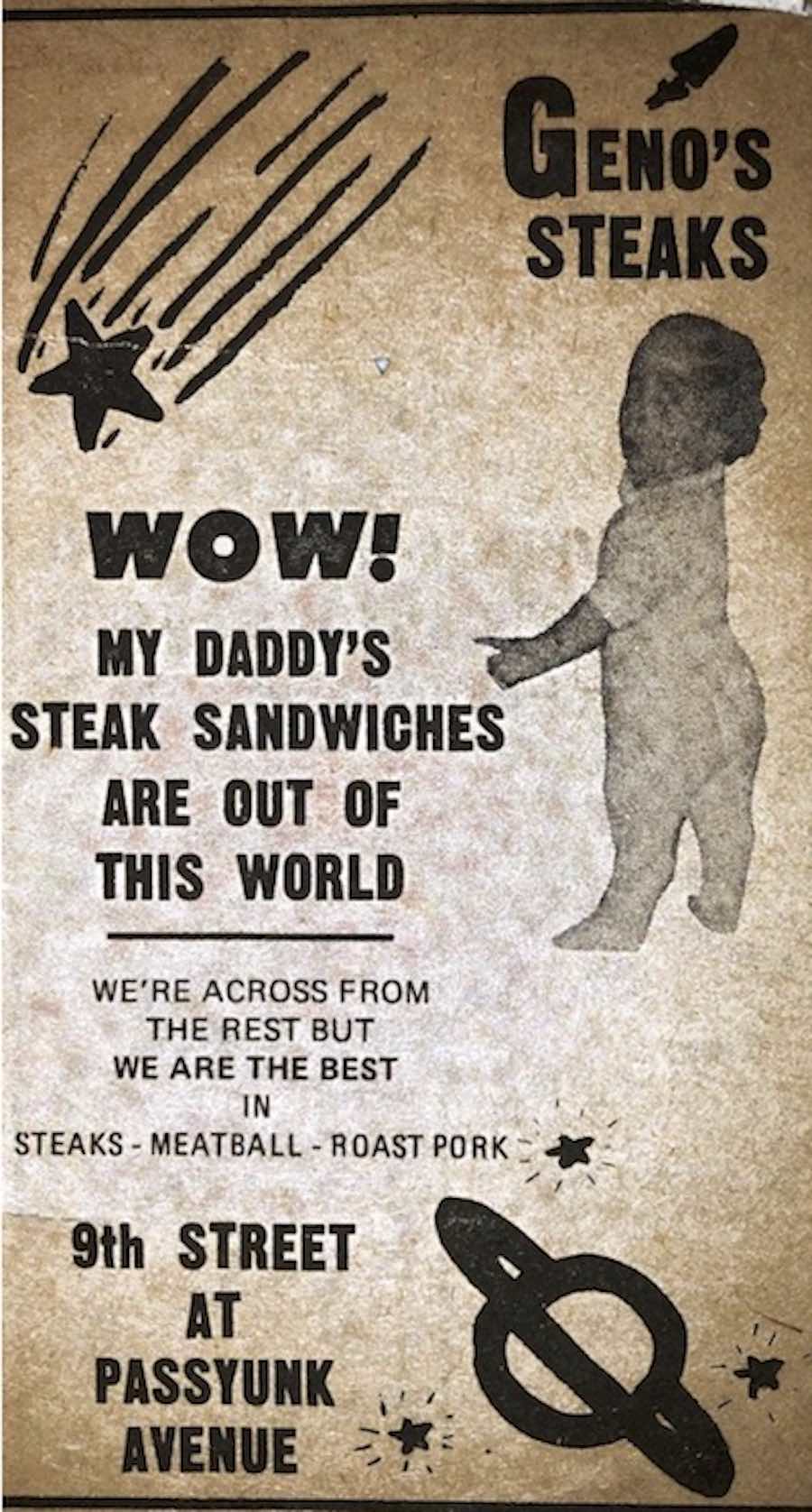

An old Geno’s Steaks ad (courtesy Geno Vento/Geno’s Steaks)

Joey Vento, owner, Geno’s Steaks: That guy across the street. He claims he invented the steak sandwich. I’ll give him that. He claims he invented the Whiz. Okay. I’ll give him that. All I did was come along and perfect it. And I started out with just a $2,000 investment. Before Geno’s, my father did steaks in this neighborhood, where the playground is near Passyunk and Wharton. It used to be a cemetery. He had a little cart over there. And then he opened up a shop, and I worked for him. But then in 1957, I volunteered for the draft, and then, unfortunately, my father had a problem, and so I come home, try to help the family, but we lost everything.

Celeste Morello: Joey Vento’s family had some rough times. I don’t know if that’s something he is going to want to get into, but it probably doesn’t hurt to ask.

Joey Vento: A guy owed my father money, and my father went out and killed him, went to jail for life. My father went to jail at the age of 36 and died in prison at 46 years old. I never saw my father after he was 36 years old. My brother was a gangster, probably done every illegal activity he could in the city. So I got the $2,000 to open Geno’s from my wife’s father, who was a bookie.

Frank Olivieri: He originally had it spelled Gino’s. But there was already Gino’s by Gino Marchetti the football player — the hamburger place. So they convinced him to change the name to Geno’s. The building he’s in was actually condemned at the time. He turned it into Las Vegas.

Joey Vento: I’ve never changed my sandwich. So even with that guy across the street, I think I’m more authentic than he is. He changed. His meat’s different now. He’s into the chopped-meat thing. But the Philly steak needs to be really thinly sliced rib eye. That’s how it started out.

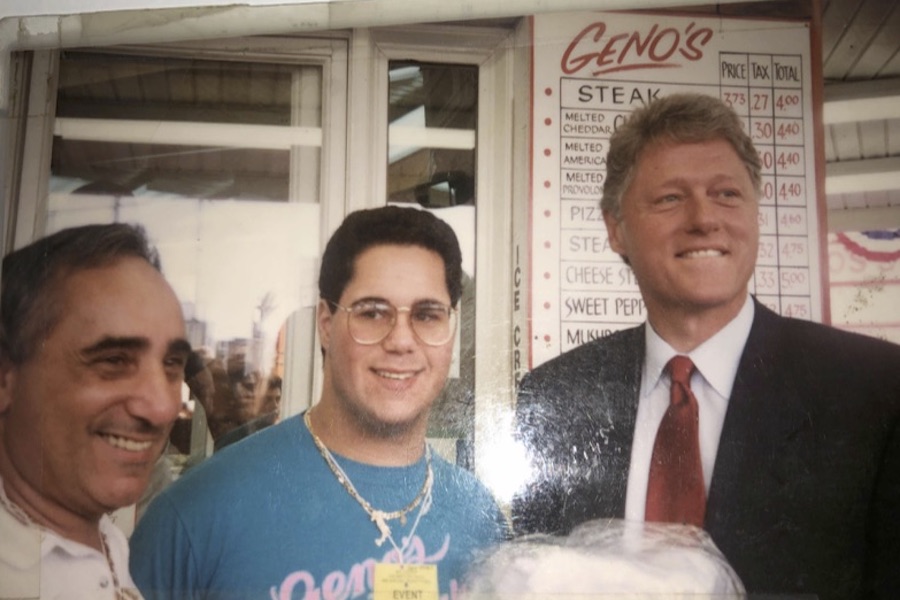

From left to right: Joey Vento, Geno Vento and Bill Clinton at Geno’s Steaks in 1996. (Photo courtesy Geno Vento)

Frank Olivieri: The real rivalry between Pat’s and Geno’s started as something that the media did, I think. I would say it was probably as early as 1970, 1973, around there. We started getting publicity. And people would come down here, and it was exciting. And then the whole Rocky thing began in 1976, and the media would say, “Well, Pat’s is doing this. What’s Geno’s doing?” You know, trying to start a fire.

Bill Proetto: I had purchased Jim’s around 1965. Then right around the time that cheesesteaks were really coming into their own, we opened South Street, on July 4, 1976, for the Bicentennial. South Street was very dangerous at the time, not like it is today. We weren’t really doing so well, but then your magazine named us in ’77 or ’78 the best cheesesteak in the city. And business really took off.

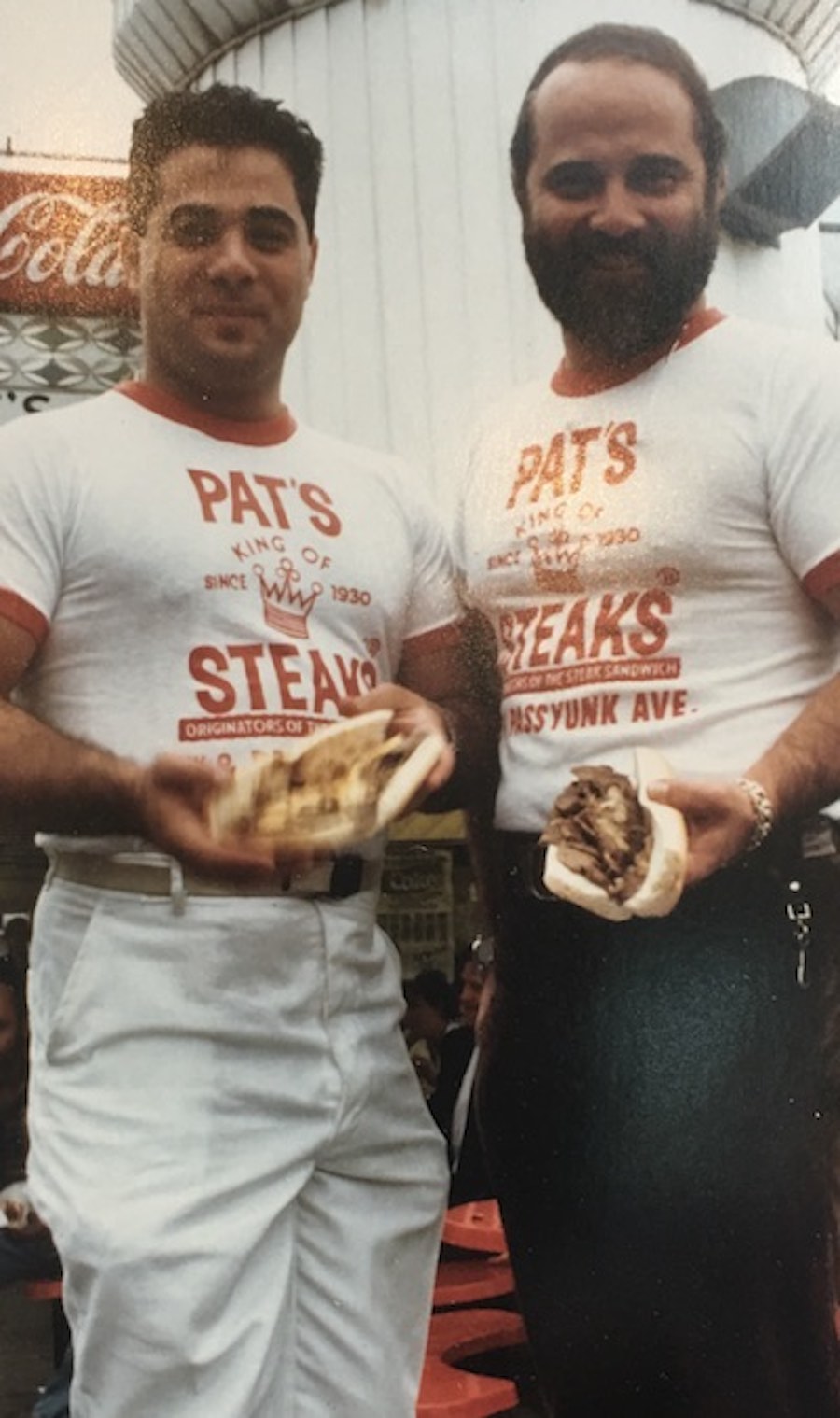

Current Pat’s Steaks operator Frank Olivieri with his father in the early 80s. (Photo courtesy Frank Olivieri/Pat’s Steaks)

Maury Z. Levy, editor of Philadelphia magazine from 1970 to 1980: When we first started Best of Philly, way back when, there weren’t a ton of places around, at least not a lot of great ones, so the argument was always Pat’s or Geno’s, and everybody sort of gave into that. So we searched out other places, within Center City and some of the neighborhoods, and one of the first places we gave it to was Jim’s on South. We tried it and loved it. I think that helped them significantly. Over the years, the cheesesteak award was one of the things that people got most upset about. You rarely heard, “That was a great pick.” You heard, “Are you guys out of your fucking minds??

Craig LaBan, food critic, Philadelphia Inquirer: It’s one of those foods that cut across all classes and generations. When you write about cheesesteaks, you hear from 500,000 people. It’s one of those “moments” foods. People remember the cheesesteak they had with their buddy. It represents things other than just lunch. You’ve been in a place where characters are still part of the lore and experience.

Celeste Morello: During the ’70s and ’80s, fast food really started taking hold. Frankie claims that he never had to advertise. Geno’s is another matter.

Frank Olivieri: It was around the same time as Rocky. Sylvester Stallone came down here and spoke to my father and said, “You know, I’m interested in filming this movie here,” and my father was like, “Okay,” and Stallone says, “Well, we’re going to close you down.” So my father says, “Well, if you’re going to close us down, you gotta pay us what we normally make.” I guess they arrived at a number. … Stallone was really a nobody at the time.

Joey Vento: Back in those days, this was all Italian. Actually, it was only in the last four, five years that I’ve seen any really big changes, with the different immigrants coming in and the different languages. My orders started getting messed up. We were hiring people who didn’t understand the language. And then the big political thing came up. But we’re just trying to serve a sandwich here.

Frank Olivieri: Joe is arrogant, but not ignorant. The competition really keeps us going. Joe Vento is like Plankton. And we are like Krusty Krab. And he’s trying to steal our recipe all the time. He’ll fire employees, and then they come over to our place and work here for a couple of weeks and find out what to do and how many we’re selling, and then they quit. And we play along with it, because it’s really no secret. And we sell 10 to one. For every one sandwich he sells, I sell 10 more. Our baker was until recently the same baker, so I know how many he was selling.

Joey Vento: Oh, is that so? I say put your money where your mouth’s at. It was a hot-dog cart when you started, and 70 years later it still looks like a hot-dog cart.

Holly Moore, food blogger: Some people have a knee-jerk reaction that says Pat’s is horrible. Pat’s is where it all started. You stand in line, and it’s two-thirds to three-quarters South Philadelphians. They may not serve the best. But they serve a great sandwich. People love to put good things down. But there’s no greater fun than to stand at 9th and Passyunk to do the eat-off between Geno’s and Pat’s and decide for yourself. It’s the real South Philadelphia. About four years ago, PBS did a special on sandwiches, and I was the host for the Philadelphia portion. We were filming down at Pat’s, and we noticed that it’s the same as team spirit, when you talk to people about their favorite cheesesteaks. It’s like being a Phillies fan, or graduating from Cardinal Whatever high school. It’s very much a part of being a Philadelphian.

Bill Clinton at Pat’s Steaks in 1996. (AP Photo/Greg Gibson)

Congressman Bob Brady: When Clinton was campaigning in ’96, he came here for a fund-raiser, and he had an hour of downtime. So myself, Clinton and Rendell, we went down to Pat’s. I got the steaks and brought them to the President.

He starts pulling it towards his mouth. I said, “Wait, you can’t sit down. You gotta stand up.” And so he stands up and brings it to his mouth, and I said, “Whoa, whoa, you gotta lean forward on the ledge.” So he leans forward on the ledge and pulls it up to his mouth again. And I said, “Wait a minute, you gotta tuck your tie in.” So he tucks his tie in, takes a bite, and sure enough a whole load of it spills out the back onto the ledge. I said, “I told you.”

That night at the fund-raiser, he told everybody that the best thing he learned today was how to eat a cheesesteak: “You gotta stand up, lean over, and stick your tie in.” I taught him that. Rendell likes to take credit for it. But that’s bullshit. I was the one who taught him the South Philly lean.

Joseph Torsella, president and CEO, the National Constitution Center: When the United States Olympic Committee came for their official site visit in 2006, they passed up our offer of a catered lunch from any of Philadelphia’s finest restaurants. They said, “Thanks, but no thanks — we’re going to hail cabs so we can go get real Philly cheesesteaks.”

Meryl Levitz, president and CEO, the Greater Philadelphia Tourism Marketing Corporation: Everyone feels like they have to have one when they come here. It’s just like the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall. It combines the interest in quality with the true grit of the place; it’s something that everyone can be a part of. Of course, you have to do it right. You can’t have somebody like Senator Kerry come in and pick some windsurfer or parasailing kind of cheese.

Washington Post, August 13, 2003:

[T]he Massachusetts Democrat went to Pat’s Steaks and ordered a cheesesteak — with Swiss cheese. If that weren’t bad enough, the candidate asked photographers not to take his picture while he ate his sandwich; shutters clicked anyway, and Kerry was caught nibbling daintily at his sandwich — another serious faux pas. “It will doom his candidacy in Philadelphia,” predicted Craig LaBan, food critic for the Philadelphia Inquirer, which broke the Sandwich Scandal. After all, Philly cheesesteaks come with Cheez Whiz, or occasionally American or provolone. But Swiss cheese? “In Philadelphia, that’s an alternative lifestyle,” LaBan explained.

–

John Kerry during his infamous cheesesteak visit (Getty Images)

Michael Smerconish, radio talk-show host: Kerry produced a tremendous amount of call-in response. People were asking, “How can you govern if you don’t know how to order a cheesesteak?” I thought at the time that it was such a snapshot of who Kerry was, the effete Kerry.

Maury Z. Levy: People who aren’t from here are appalled by the idea of Cheez Whiz: “What? People don’t really eat that!” Some think it’s worse than Spam. We had the original junk food.

Basil Maglaris, spokesman, Kraft Foods: The Philadelphia/South Jersey market accounts for approximately one-quarter of our total Cheez Whiz food-service sales in the U.S. And the same market accounts for 50 percent of our American White Cheese Slices, as it’s another popular ingredient in the Philly cheesesteak.

Holly Moore: Any time it says “Philly” in front of the name, don’t get it. They’re pretenders if they have to use the word Philly. I stopped trying cheesesteaks throughout the country when at a California farmers’ market they offered me a choice of toppings: bean sprouts or avocado.

Maury Z. Levy: The first time I was in L.A., the menu at this restaurant said “cheesesteak,” so I said, “Oh great, I’ll have that.” It was literally a sirloin steak with a glob of cheese on top and a big steak roll. It’s still funny to see them in other cities. But if you were born here or grew up here, you know the secret formula.

Dave London, owner, The Philly Way, Milwaukee: I used to work in radio in the Philly area — ’YSP, ’MMR, WIFI 92. And then I got a job that sent me out to Milwaukee in 1990 to run a station. I got bored, and I had a culinary background. I had even worked at Pat’s in the ’70s.

For a time, I was working as a tour manager for Dustin Diamond — Screech from Saved By the Bell — and we were in town at Temple. I went down for a steak, and it was at that moment that I decided to go back to Milwaukee to show them what a cheesesteak was really like. When I opened six years ago, there was just one other cheesesteak place out here. The guy was from Jersey. And so I went in and tried it — he had a bunch of other foods, an enormous menu — and I asked for a Whiz wit’, and he said, “We don’t have that.” And I thought, That’s it. This guy doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

From day one, I exploded, and then a few years ago, your magazine did that article about cheesesteaks around the country and named mine the best. And that really just set us off in a whole new way. The sandwich of Milwaukee is the brat. When the Phillies were in town a couple of years ago, there was a contest at the park pitting my cheesesteak against the guy who is said to do the best brats in town. I won.

Customers and staff inside the South Street location of Jim’s Steaks in 1977. (Photo courtesy Jim’s Steaks)

Maury Z. Levy: Every other city in the world, when someone asks you what school you went to, they mean college. In Philly when someone asks you that, they mean high school. Sometimes junior high school. It’s a working-class food. It’s the stuff you ate growing up. It was good. No matter how successful or fancy you got, you never forgot your roots. We have loyalty. And you can’t shame us into not eating this stuff. We don’t care who you are.

Chuck Peruto Jr., criminal defense attorney: I was representing — I guess you could call him a Mob boss — Harry Riccobene when he was feuding with Nicky Scarfo back in the 1980s. It was very well publicized. They were killing each others’ families. At the height of these Mob wars, I went to visit Harry at the detention center. It was an incredibly high-security facility. And as we’re talking, a guard walks over with a bag. Inside, a Geno’s cheesesteak. Harry shared it with me.

Holly Moore: Every city I go to, I can find a great hamburger stand or a great hot-dog stand very easily. But in Philly, the cheesesteak is so dominant that they’ve squeezed out the cheeseburger/hot-dog place. I could open one up at 9th and Passyunk and I would go out of business. People will just eat their cheesesteaks.

Maury Z. Levy: You see the allegiance to the cheesesteak when you go to a ball game. If you don’t get to Ashburn Alley early enough, you could be standing there for the first three innings just waiting for your steak. There are a lot of ballparks with good food, but that kind of religious loyalty doesn’t happen anywhere but in Philadelphia. When the park first opened, we’d go with friends and family and argue which steak place to go to: “Wait a minute, I like this one.” You like that one. It gets very scientific: The steak is good, but the roll sucks. It has to be a great roll, not smushed with grease. The cheese becomes a part of it, too — how it melts. People will just argue forever about their cheesesteaks.

Craig LaBan: It’s very hard to replicate on a mass-production level. It takes skill, know-how, primal knowledge in your DNA of what it’s supposed to taste like. There’s something that will be forever local about it, and I think that gets to the heart of its greatness, because it’s a sandwich that speaks to this place, and regional foods are so rare now in America. So that’s why you have a local pride. That doesn’t explain why people eat thousands of bad cheesesteaks every day, but it does explain why people approach it as a local sport.

On a more national scale, you sort of still have the great cheesesteak artisans. They take pride in their ingredients, how they’re cooked. There is a clear hierarchy. When you hear that clink of frozen meat hitting the griddle and there’s some high-school kid behind it, you just know there’s going to be a difference. Because it’s an art.

Holly Moore: I think that if Tony Luke’s or John’s had gotten to Pat’s location first and was doing the pork sandwich, then the city’s sandwich would probably have been the pork. I look forward to a pork sandwich more than a cheesesteak. Tommy DiNic’s at Reading Terminal, I’d rather have that any time. But if I think of the soul of Philadelphia, I think cheesesteaks.