REVIEW: A Quiet Place—Leonard Bernstein’s Chilly Winter Garden

Without its companion pieced, Trouble in Tahiti, this difficult late work feels like half of an opera.

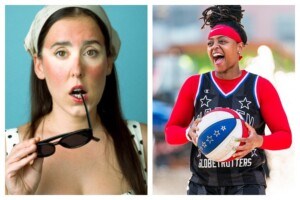

Ashley Milanese and Tyler Zimmerman in A Quiet Place at the Perelman Theater. (Photo by Paula Court)

Leonard Bernstein liked his gardens. “We’ll build our house and chop our wood / and make our garden grow,” the ensemble sings at the close of Candide. In Trouble in Tahiti, the opera where we first meet Sam and Dinah—the conflicted married couple whose story continues in A Quiet Place—Dinah remembers a voice calling out to her in a dream: “There is a garden… a shining garden… come and see. There love will teach us harmony and grace.” In both cases, the preceding action has often been harrowing. But although Bernstein, perhaps our most ebullient and energetic composer, never shied away from emotionally wrenching topics, he finds optimism in this metaphor. Surely the couples here can find a way to grow and flower.

- The Wanamaker Building Reawakens With a Series of Performances This Fall

- Anthony Roth Costanzo Is Here to Save Opera in Philly

- The Cocktail Making a ‘Buzz’ at Opera Philadelphia

- At Least Three Philly Gas Stations Are Now Using Opera to Fight Crime

- What Will Philly’s Arts Scene Look Like After a Year Without Audiences?

Yet, in A Quiet Place—seen here in a co-production of Curtis Opera Theatre, and Opera Philadelphia—well, ‘tis an unweeded garden that grows to seed. When the action begins, we’re at Dinah’s funeral. (She was killed in a car crash; she also had suicidal impulses.) Sam awaits the return of his son, Junior, and daughter, Dede and her husband, François. The four of them pretty much define complicated. François was Junior’s lover before marrying Dede. Junior has what seem to be traces of OCD, as well as rage issues. Nobody gets along with anybody else, at least not for more than a few minutes at a time. Can there ever be a sense of mutual understanding?

A Quiet Place is surely one of Bernstein’s darkest pieces, though there are moments of biting satire, as in Dede’s sardonic little arioso about the fall colors—also some passages, especially the orchestral interludes, of translucent beauty, and jazzy riffs that recall West Side Story. But it’s difficult to empathize with any of the characters, and much of the situation feels like the kind of party you’d flee after five minutes.

The Curtis forces—especially conductor Corrado Rovaris and his orchestra—make a persuasive argument for the piece. Soprano Ashley Milanese is a superb Dede, dramatically committed and with a soaring lyric soprano capable of heart-stopping soft effects. Playing François—a Quebecois, whose dialogue is in a mix of French and English—the Montreal-born Jean-Michel Richer brought a welcome sense of fluency. Tyler Zimmerman made a sincere Sam, and he has a fine, resonant baritone, but Zimmerman looked far too youthful in a role made for middle-age.

Junior is a problematic part for sure, a troubled (and troubling) compendium of tics and oddities—this is often how “gay” was signified in writing from an earlier time, but one hoped for more from Bernstein and librettist Stephen Wadsworth. Nonetheless, Dennis Chmelensky was often captivating in the role—a presence for sure, decked out here with androgynous ellusiveness, and also seeming appropriately vulnerable. Chmelensky’s dark baritone has a strikingly individual timbre, but the words were often occluded, and his singing (admittedly, in some of the least graceful vocal lines ever composed by Bernstein) occasionally pitchy. Among the ensemble, mezzo Anastasiia Sidorova and tenor Aaron Crouch made especially positive impressions.

Director Daniel Fish’s sleek, pared-down production scores major points visually, but it doesn’t help the already fragmented A Quiet Place to make it more abstract. Fish excessively reinforces the characters’ isolation by placing his cast in inert poses (seated on the floor for much of Act III, for example), even as the libretto makes it clear that the family is engaged in an emotional chess game. This compounds the problems in Wadsworth’s libretto, which is by far the weakest element of A Quiet Place—pretentious, overblown, abstruse.

But the biggest problem here is that A Quiet Place, in a skillfully orchestrated chamber version by Garth Edwin Sunderland, feels incomplete. Earlier versions incorporated Trouble in Tahiti (either as a first half, or later, inserted within the score). Trouble fleshes out the story—the tunefulness of that score balances the much more deconstructed A Quiet Place, which also uses a lot of thematic material from Trouble. Without the pairing, A Quiet Place feels drained of life—Leonard Bernstein’s garden in the chilly grip of winter.

A Quiet Place has performances on March 9 and 11. For more information, visit the Opera Philadelphia website.