Find Your Philly Dream House. (At Last!)

What’s hot? What’s not? And where can you get a great deal? Here’s everything you need to know about Philly real estate right now.

Trey, the goldendoodle, poses next to a custom doghouse built by local craftsman Matthew Englebert. Photograph by Colin Lenton

“We are having an inventory crisis,” Lauren Leithead tells me matter-of-factly.

The two of us are having omelets at Sabrina’s Cafe in Wynnewood, and I catch myself being pleasantly surprised by how lively and diverse the suburban crowd is at noon on a weekday. Were it not for the SUV-filled parking lot and the Lulu-clad moms streaming into Pure Barre next door, I could just as easily be at one of Sabrina’s bustling downtown locations.

“Inventory is the lowest it’s been in 14 years,” Leithead continues. She’s referring not to the dearth of Nick Foles gear on the shelves of the City Avenue Target, but to the real estate market on the Main Line, where she’s been a realtor (she’s with Keller Williams) for more than 15 years.

A few days later, Noah Ostroff echoes Leithead’s insight on the phone from the Center City office of his realty group, PhillyLiving Keller Williams. “There have been 32 consecutive months of year-over-year decline in inventory in the city,” he tells me.

Assuming you’re not in the real estate biz, what does this mean? Well, if you’re one of the many Philadelphians on the hunt for a new house, it suggests there really aren’t many unicorns out there. With so few options to choose from, gone are the days of getting everything on your checklist — for a steal. If you’re a seller, you may be in the driver’s seat — but not necessarily in a position to make bank. That’s because in many parts of our region, prices still haven’t climbed back to where they were in 2007 (more on that later). So sure, you can unload your house in fewer days — but not with a dramatic profit.

Even if you’re not buying or selling, though, the demand for inventory says something deeper about Philly: Our real estate market is healthier than it’s been since the economy cratered a decade ago, and in many places (read: the city), it’s certifiably hot.

In 2017, the number of homes sold in the eight-county metro region was the highest it’s been in the last decade, and in the past three years, the number of days houses are on the market has dropped by approximately 20 percent. People are buying; houses are moving.

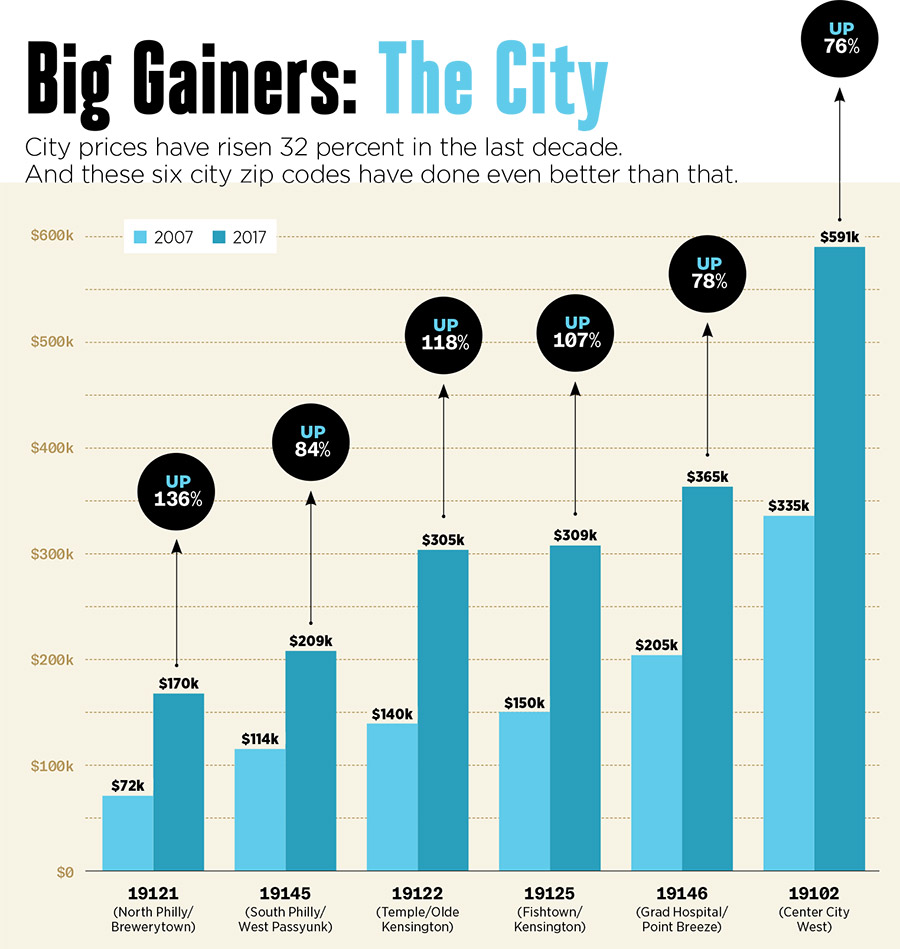

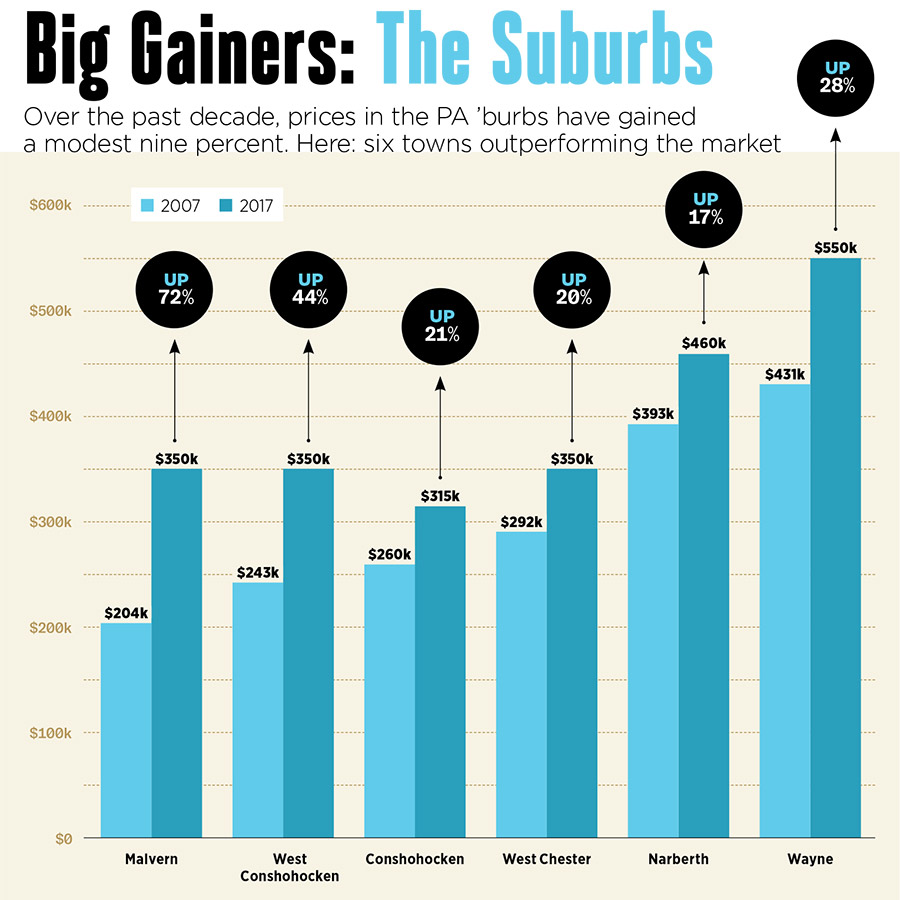

As for prices, that very much depends on where you are. In the city, median prices are now a whopping 32 percent higher than they were a decade ago, with certain city neighborhoods up nearly 75 percent. But median prices in the Pennsylvania suburbs are up by only nine percent. As a general rule, Greater Philadelphia is neither an overheated market nor unattainable for the masses. We have something for everyone.

Here’s how that came to be — and where we might be headed next.

I. The State of the City

Cities nationwide are collectively more welcoming and more desirable — and Philly, in particular, is thriving. We’ve always had history, but now more than ever, we have booming medical and academic anchors, stellar restaurants and world-class arts. And while cities like New York and Boston have seen home prices skyrocket, ours have risen more gradually and remain much more affordable, relatively speaking. All of this has made us attractive to buyers who 10 years ago might have sought out other major cities — and to millennials who, bursting with big ideas but collectively saddled with student debt, have turned a compromise city into a major destination.

“The city is cool again,” says Mickey Pascarella, principal of the Mickey Group at Keller Williams Center City. For decades, Pascarella says, Philly was in decline due to factors like job loss, redlining, crime, and a general preference for suburban life. But that’s reversing at an aggressive pace. If you look at Philly 10 years ago vs. now, the city has changed dramatically.

In 2008, if you couldn’t afford to live in the Rittenhouse area, Pascarella says, you could have bought “a big new home with parking and a massive roof deck in Graduate Hospital for $425,000”; now, that house would cost significantly more. In fact, in the decade between 2007 and 2017, median sale prices in Grad Hospital rose a healthy 75 percent. “And what’s happened, very predictably,” Pascarella continues, “is that people who now can’t afford Graduate Hospital will go across the street to live in Point Breeze. Places like American Sardine Bar will open up.” Suddenly, a neighborhood starts building buzz, and more would-be buyers begin looking there. It’s happened throughout the city. Think: Northern Liberties spilling into Fishtown, Fishtown spilling into Kensington.

So, where will the next hot neighborhood be — and where can you get a deal now? “The term ‘deal’ is a relative one,” Ostroff says. If you can’t afford Rittenhouse — where the average home price in the last quarter of 2017 was $793,000 — you can go to Graduate Hospital, Grays Ferry or Point Breeze, where the average was $395,000. If you can’t afford Society Hill or Old City and their average price of $594,000? There’s Queen Village/Bella Vista ($523,000) and their southern neighbor, the 19148 zip code ($222,000). If you can’t afford Northern Liberties ($489,000), there’s Fishtown ($338,000) or the 19122 zip code, which includes Olde Kensington and parts of North Philly near Temple ($311,000).

Reid Rosenthal, associate broker at the Rosenthal Group at Berkshire Hathaway HomeServices Fox & Roach, is more direct. “If you’re speculating a little bit? I would say the western part of Point Breeze — that’s one place you can get a deal. There’s also Newbold, which is closer to Broad Street, east of Point Breeze. And even areas like West Powelton Village in University City, Pennsport, southern parts of Passyunk Square, and also Francisville, which is [essentially] the northeastern part of the Art Museum area.”

Of course, no discussion of cities is complete without mention of gentrification. How do you embrace its positive contributions while keeping its negative effects — the pricing-out of longstanding members of a community, the loss of character of a neighborhood — at bay? “Gentrification is a phenomenon of cities that is unavoidable,” says Benjamin J. Keys, assistant professor of real estate at Wharton. “There was gentrification in ancient Rome!”

Some City Council members argue that the answer is to require a certain portion of more affordable housing in new residential buildings. Pascarella argues that this is inadequate. “It doesn’t provide enough units,” he says. “We need thousands and thousands of units for people being displaced.”

Keys agrees. “The short answer is that we build,” he says. We build up, he adds. And we build around transportation, so we can be less dependent on cars. It’s a very challenging thing for a government to engineer, he notes, because market forces are so powerful. And it can only be done with federal, state and local support: “You need a cohesive plan that doesn’t just isolate lower-income residents in housing projects, but instead integrates them into the community.”

It’s the kind of insight that requires true community engagement — perhaps starting with having more residents, new and old, attend Council meetings. (Imagine if all new leases and deeds included a civic participation requirement.)

II. The Suburban Ripple

If downtown is the epicenter of the real estate boom, you might expect that the suburbs should feel a spillover effect. But not all suburbs are created equal, nor have they responded to the market rebound in the same way.

“The city’s on fire, but the Main Line luxury market is still depressed,” says Robin Gordon, of the Robin Gordon Group at Berkshire Hathaway HomeServices Fox & Roach, which did $178 million in sales in 2017. A lot of owners who bought homes for more than $1 million just before the economic crash in 2008 are holding onto those homes, hoping prices will rebound. That’s fueling a lack of inventory; meanwhile, most demand is for homes under $1 million — which, Gordon says, are selling quickly, especially in the Main Line’s most walkable zip codes.

“I think the millennials who stayed in the city longer are now starting to swing out to the suburbs,” Gordon explains. “Downtown was very convenient and walkable, and now they don’t want huge McMansions on acres of grounds; they want walkability to a town or a train. So Wynnewood’s been really hot, Haverford, Bryn Mawr, Ardmore, Narberth.”

Hot they may be, but overpriced they’re not: If Center City is on fire, the same can’t be said for the suburbs. “We haven’t seen a [major] price hike as a result of the lack of inventory,” Gordon says. Whereas median city prices are a third higher than they were a decade ago, only two suburban counties have even gotten back to where they were then. (Chester County is up eight percent, and Montgomery County is up three percent.)

“In many parts of the metro area, the Great Recession, in a sense, hasn’t ended,” says Wharton’s Keys. “Parts of the suburbs haven’t fully recovered.”

That said, particularly in the Pennsylvania suburbs, there’s been enough activity in the past couple of years to have people feeling optimistic. “I’m third-generation Philadelphian,” says Gordon. “I went to Penn, I’ve been working in real estate on the Main Line for nearly 30 years, and I’ve watched these cycles. I think the Main Line is heading on an upward path.”

For now, the best deals may not spring from a certain zip code, but rather from a type of home. “A lot of luxury homes over $1.5 million have been on the market a while now, and their prices just keep coming down,” Gordon says. “And it’s either because they’re dated-updated, meaning they were updated 10 to 18 years ago, or they’re just totally outdated. They need a full reno. They’re trickier to sell, and if you find one that’s been on the market for a while, you probably could get a good deal.” At, ahem, $1.5 million. (And people are taking advantage of those deals. The fourth quarter of 2017 saw more million-dollar home sales than any Q4 since 2005.)

Like the Main Line luxury market, South Jersey is another outlier. Prices in every single town in Gloucester County, for example, have declined since 2007. Of the 34 towns in Camden County’s MLS area, only one — Haddonfield Borough — has seen a median home price increase over the past decade. Philadelphia economist Kevin Gillen explains why: First, New Jersey has one of the longest foreclosure timelines of any state in the country. “If you get a good lawyer, you can basically live mortgage-free for seven or eight years,” he says. There are still a lot of homes in foreclosure, and that depresses the homes surrounding them. On top of that, Gillen says, the economy in South Jersey is still very challenged, with casino closures and vacant strip malls partly to blame.

Even with those challenges, South Jersey realtors say, homes at the most desirable price points are going fast. “In Cherry Hill, Mount Laurel and even parts of Gloucester County, like Washington Township, if it’s priced right, it’s going to sell with multiple offers in a couple of days,” says Mary Murphy, of Keller Williams in Cherry Hill. “Anything in that $150,000-to-$300,000 range and even in the $400,000 range will go quickly.” Especially, she adds, when it comes to new construction.

III. Seeing the Future

Fun fact: Over the course of the months I spent reporting this piece, mortgage rates changed more dramatically than even the most in-the-know economists would have predicted. They were at less than four percent in the fall of 2017. (For comparison, in 2007, rates reached as high as 6.7 percent.) But by early March, they’d jumped to 4.5 percent, causing some buyers to freak out.

“The smartest people in the world didn’t see this coming,” says Trevor Tashlik, vice president of mortgage lending at Guaranteed Rate in Center City. “The shock is just how quickly the rates have gone up. Whereas if it would have happened over a year, it would be a little easier to digest.” How does that translate to actual dollars? Not significantly. “It’s about $30 per $100,000 you’re borrowing,” Tashlik explains. “So if a borrower is mortgaging $300,000, that’s a $90 difference in their monthly payment. You spend more than that at Wawa every month.”

Will rates continue to rise or stabilize? No one’s totally sure. But the other factor that could affect the real estate market is the new federal tax laws that were enacted this year. As Keys explains it, there are three pieces at play.

First: The limit on the mortgage interest deduction has been lowered from $1 million to $750,000. To clarify: That refers to the interest on the first $750,000 of mortgage debt and only affects new mortgages — previous mortgages have been grandfathered in. So that’s going to be an issue only at the very high end of the market.

The second piece is the change in the standard deduction: Married couples can now take a deduction of $24,000, and singles can deduct $12,000. This means that painstakingly itemizing your mortgage interest and state and local taxes may no longer be necessary or desirable. “In many cases, households that previously itemized will find that it’s actually better if they use the standard deduction,” Keys says. In effect, this could remove one of the incentives for buying a house.

But that brings us to the third piece of the equation, which complicates the second one a bit: the change to the deductibility of state and local taxes. “It used to be the case that you could deduct all property taxes paid to the state and local governments. But now, there’s a cap of $10,000 — in total, whether you’re single or married,” Keys explains. This, he says, is going to have a big impact on home buyers who aren’t willing to take on the full cost of the property taxes: “In the past, you could sort of think of getting a discount on your property taxes, but this is going to force home buyers to bear the full burden of them.”

So does that argue for renting? Not necessarily. It’s hard to tell at the moment whether it’s conclusively a better idea to rent or buy, says Shantanu Sharma, a Goldman Sachs alum who co-founded Philly-based STEM Lending last May with the goal of making the mortgage process more transparent, particularly for millennials. There are two aspects to home ownership, he points out: “One is the purely financial aspect of things: How is it as an investment? And the other is the cultural aspect of home ownership. There’s a sense of pride and an emotional aspect of home ownership. You have to consider both sides of the coin.”

“Housing is first and foremost a place to live and spend time with your family,” Gillen says. “And what got us in trouble with the housing bubble is that people started to think of housing as primarily an investment and a way to get rich quick, rather than as a consumption good. If you’re buying a home to live in and not as an income property, the time to buy shouldn’t be the most salient factor in the decision.” It can be a mistake, he says, to buy based solely on market conditions.

IV. Philly vs. the World

Compared to a decade ago, Philly has decidedly come into its own. We aren’t New York. We aren’t D.C. We aren’t L.A. or San Francisco. And that’s a good thing. (Oh, and did you hear? The Eagles won the Super Bowl.)

Back over breakfast in Wynnewood, Leithead puts it this way: “I’ve had clients move here from other cities and they’re like, ‘I could never buy in Boston! I could never buy in New York!’ But you can buy in Philadelphia. You can buy a really nice home in a beautiful area near culture and history at a very affordable price. And you can’t say that about our sort-of competing cities — D.C., New York and Boston. They’re ridiculous.”

That may be the greatest real estate pitch of all for our region — Philly: We’re not ridiculous.

Five Philly Couples Who Hit Real Estate Pay Dirt

The stories of five families and their fantastic new homes. Read more »

11 Tips for Going to Market, Whether You’re Buying or Selling

Local real estate experts weigh in. Read more »

What’s Happening in Your Neighborhood?

Our searchable town-by-town price and sales report for the eight-county Greater Philadelphia area. Read more »

Published in the April 2018 issue of Philadelphia magazine.