A Century Later, the Parkway’s Grand Vision May Finally Come True

The Ben Franklin Parkway is one of Philadelphia’s most dangerous roads — not to mention an abysmal place to walk. The solution? Redesign the entire thing.

The Benjamin Franklin Parkway / Photograph via Getty Images

One day, nearly a decade ago, Mike Carroll sat down for a quotidian meeting of city officials at the Philadelphia Streets Department. Next to him was Kathryn Ott Lovell, then the director of the Parks and Recreation department. “It was a random meeting,” Ott Lovell recalls — not particularly memorable. That is, until Carroll flipped over the paper agenda before him, turned to Ott Lovell, and said, “You and I have to talk.” Carroll began sketching something on the page, then said flatly, “This is what we need to do.” Ott Lovell stared at the piece of paper before her: She was looking at a radical redesign of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Gone were the four lanes of car traffic separating Eakins Oval from the Art Museum steps; they’d been rerouted to below Eakins Oval. Now in their place was an open pedestrian plaza linking the Art Museum and Rocky Steps to the giant Washington Monument fountain below.

Carroll, who’s the deputy managing director of the city’s Office of Transportation and Infrastructure Systems, has been preoccupied with the Parkway’s problems virtually from the day he began working for the city more than a decade ago. During one of his first weeks as a city employee, a driver struck a bicyclist along the road; the cyclist wound up paralyzed. This got Carroll thinking about the design of the Parkway, which, he promptly realized, made no sense. Cars zoomed around Eakins Oval, merging and darting between lanes like rabid squirrels. Crosswalks were positioned at dangerous angles. And this was all in front of the Art Museum steps, which, with four million visitors a year, are the single most popular tourist site in Philly — and certainly the most photogenic. Carroll was in disbelief. “How can we be bringing people from all over the world into this condition, which is a little bit harrowing?”

A little bit harrowing is, well, a little bit of an understatement. “The big problem with Eakins Oval is everyone takes their life in their hands as they go across,” says Harris Steinberg, an urban planner who has been involved in the effort to redesign the Parkway. This is not hyperbole. The Parkway is part of the city’s high-injury road network — the 12 percent of city roads that account for 80 percent of all traffic injuries — and from 2018 to 2022, eight people were killed or seriously injured over the 0.8-mile stretch between the Art Museum and Logan Circle. (By comparison, you have to go all the way from Independence Hall to 36th Street along Chestnut — more than two and a half miles — to reach an equivalent number of injuries over the same time span.)

Being a pedestrian anywhere in Philadelphia can induce heart palpitations, but the Parkway’s design is uniquely arrhythmic. Walking along what should be a grand, majestic boulevard instead feels like strolling along the shoulder of a highway. Pedestrians must navigate an archipelago of traffic islands, with cars speeding close by. There’s one stretch, over by Eakins Oval, where the sidewalk leads to the street and then inexplicably disappears, as if it’s been swallowed up by some unknown dimension. The Norwegian fjords would seem to have a more inherent logic to them.

While the experience of navigating the length of the Parkway as a pedestrian may be terrible, the problem really begins at the Art Museum steps and Eakins Oval. What should be a place where you can stand at the top of the steps, taking in the view before heading on toward Center City, is immediately cut off by a road. “The underlying issue,” Carroll says, “is that those two spaces aren’t connected.”

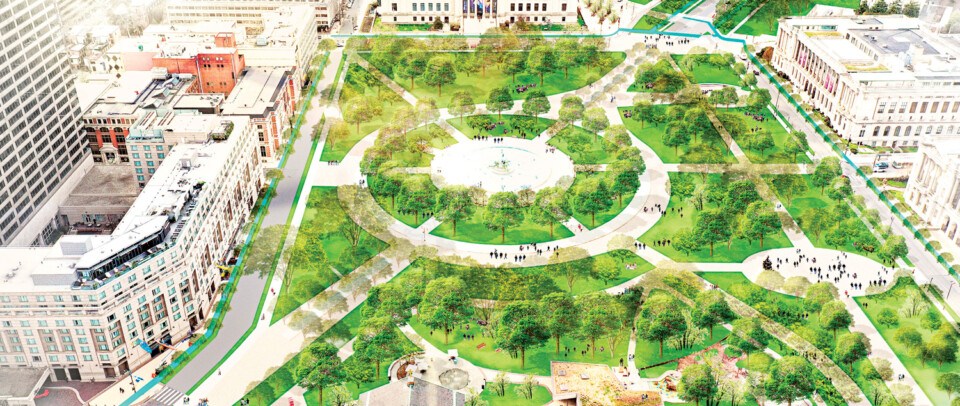

Plans call for completely overhauling Eakins Oval and removing the traffic circle. / Rendering by Design Workshop, courtesy of the Parkway Council

Carroll’s drawing has, in a few short years, kick-started what is now an incredibly ambitious plan to transform the vast majority of the Parkway — from the Art Museum all the way down to Logan Circle. The importance of the Parkway to the city should go without saying. It is something like Philadelphia’s front stoop. Thirty-four thousand people live within a 15-minute walk of it — and 850,000 within a 15-minute drive. It is where we welcome visitors; 10 million a year come there in total. It has served as the site of citywide protests. It is also where we go to celebrate and to party. It has hosted the world’s luminaries, like Jason Kelce when he sang “No one likes us, we don’t care.” It has also hosted the Pope.

In 2021, the city selected the firm Design Workshop to reimagine the Parkway. This fall will bring the release of “Parkway to Park,” a 55-page document full of colorful renderings of the plan, which would see a central plaza established between the Art Museum and Eakins Oval, the outer lanes of the Parkway permanently closed to cars and converted to green space and bike lanes, Logan Circle reconfigured from its present status as an imposing traffic circle to a pedestrian square as William Penn originally intended, and the land south of the Art Museum expanded into a seamless connection to the Schuylkill River.

All told, the project would produce 16 new acres of green space in the heart of the city — more than twice the size of Rittenhouse Square — and double the amount of tree canopy along the Parkway. The city has already been awarded a $23 million federal grant to undertake the roadway redesign that would connect the Art Museum to Eakins Oval; landscaping the new plaza and replacing the outer lanes would cost another $25 million or so. It would be a fundamentally transformative project for one of Philadelphia’s most beautiful, and also most justifiably maligned, spaces.

The Parkway has always been something of an incomplete project. In 1884, city planners first dreamed up the idea of connecting the extravagant new City Hall under construction — it would become the tallest occupied building in the world at the time of its completion in 1901 — to Fairmount Park, which had been established in 1867 and served as the site of the Centennial Exposition of 1876. To build the Parkway, more than 1,300 buildings were demolished starting in 1907, in what had been a neighborhood full of rowhomes and factories. That same year, French architect Paul Cret was commissioned to design a plan; he envisioned a kind of Parisian boulevard lined with uniform buildings and cultural institutions along its length.

Published in The Fairmount Parkway: A Pictorial Record of Development (1919), Courtesy of the Association for Public Art

A decade later, with demolition complete and a largely empty thoroughfare cutting through the city, a different Frenchman, a landscape architect named Jacques Gréber, was brought into the fold. Gréber saw the Parkway differently — as a series of small gardens, dotted with cultural institutions, that would create what he called a “wedge of greenery.” In the end, only a few of the nearly 20 planned institutions for the Parkway ended up being built: the Free Library in 1927, the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1928, the Rodin Museum in 1929, and the Franklin Institute in 1934. By then, with the Depression underway and World War II not far around the corner, progress on the Parkway stalled. By the time planners got back to thinking about the grand boulevard, the green wedge for pedestrians was no longer the priority; the automobile had commandeered all attention. Soon, Ed Bacon would build the Vine Street Expressway, creating an open trench right alongside the Parkway.

A view of the Parkway in the 1940s / Photograph by H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock/Getty Images

Maybe because of its unfinished promise, the Parkway has been the subject of proposed modifications for decades, as various planners have sought to achieve something approaching Gréber’s original vision. In 1999, the Central Philadelphia Development Corporation, a predecessor of the Center City District, released a 68-page plan appropriately titled “Completing the Benjamin Franklin Parkway.” In it were many of the same ideas being suggested today: connecting the Art Museum to Eakins Oval, recapturing Logan Circle for pedestrians, and generally making the environment less geared toward the car. The crux of the issue then, as now, was that the Parkway was mostly a place you went through, maybe while jogging or, more likely, while driving your car. Its problem, the report concluded, was that the area had “none of the infrastructure necessary for human comfort.” (That remains the case quite literally today. There are no public bathrooms at the end of the Parkway, and when tourists stop in to the Philadelphia Visitor Center outpost next to the Rocky Steps, employees direct them to the nearby Whole Foods.)

That plan never ended up materializing. It may have suffered from its ambition: The idea to connect Eakins Oval to the Art Museum required burying the existing road underground — a huge, not to mention exorbitantly expensive, infrastructure undertaking. Nor did Paul Levy, the organization’s executive director, who would go on to helm the Center City District for 30 years, have much of an audience at City Hall.

Fast-forward a decade and a different atmosphere began to emerge. “By the time the Nutter administration came into power, the good guys were now occupying the seats,” says Steinberg, the urban planner. Ott Lovell, who at the time was running the Fairmount Park Conservancy, a nonprofit that partners with Parks and Rec to maintain and improve the city’s parks, began working closely with city officials to imagine the Parkway’s next chapter. The city ultimately tapped Steinberg and PennPraxis, an urban design group he’d founded at the University of Pennsylvania, to interview citizens and neighbors and produce yet another vision for the Parkway. That plan, “More Park, Less Way,” repeated many of the same principles everyone knew — it was all right there in the clever title. Fewer cars. More pedestrian infrastructure.

But “More Park, Less Way” didn’t go as far as Levy’s vision. City Hall had sought to rein in the planners. “It was quietly recommended to us to not go too big, too far,” Steinberg recalls. “Paul had put Kelly Drive basically under Eakins Oval, and people just thought that was crazy. It may be, it may not be, but there was, I think, a concern that we would go too pie-in-the-sky.”

Pragmatism paid off this time. “More Park, Less Way” led to the Oval, the pop-up space with a beer garden, mini golf, film screenings, and other events that replaces the parking lot in front of the Art Museum every summer. “Why are we parking on what could be a great public space?” Steinberg recalls thinking. That question, he says, “captured the public imagination” and helped make the Oval a reality. By all accounts, the Oval has been a success — 65,000 people visit it every year. It has also served as a sort of proof of concept: Give people an actual reason to come to the Parkway, and they will.

On a sweltering morning in late July, Nick Anderson stands at the base of a checkerboard mural adorning the Eakins Oval parking lot. Anderson is the executive director and current sole employee of the Parkway Council, the nonprofit spearheading the most recent round of redevelopment planning. Anderson looks out at the Art Museum bathed in golden light, a few brave runners prancing up and down the steps, and appraises the status quo. “This is basically a glorified traffic island,” he says. “The goal is that it feels like this park space with this seamless connection to the Art Museum that really is the beginning of a continuous feeling of park into the city.”

Getting rid of the road between the Art Museum and Eakins Oval could very well accomplish that. But walking with Anderson reveals the magnitude of the space’s problems. Over by the museum, one of the two fountains is turned off. Chunks of the sidewalk are cracked and patches of grass are dead, leaving blotches of dirt across the not-so-green space. “The big challenge is the city’s Parks and Rec department is pretty underfunded compared to peer cities,” Anderson says diplomatically. (The city spends $104 per resident on its parks — which ranks 66th in the country — roughly half that of places like Chicago, Denver, and New York City.)

Anderson strolls toward Logan Circle under the blanket of shade generously produced by the London plane trees on either side of him. To his right, traffic rumbles up the center lanes of the Parkway. To his left, traffic rumbles slightly less slowly up the outer lanes. The entire way down the road, Anderson doesn’t encounter a single person sitting around; everyone is either walking or running — bouncing between the disconnected traffic islands and sidewalks and, ultimately, going somewhere else.

Not so long ago, the Parkway Council was itself as incohesive as the road from which it takes its name. The organization, which was originally founded as the Friends of Logan Square Foundation in 1984, was made up of the leaders of the institutions along the Parkway: places like the Art Museum, the Barnes Foundation, the Rodin Museum, the Franklin Institute. The Parkway Council met regularly, but it had almost nothing to say about the future of the shared boulevard. Instead, according to Scott Cooper, the CEO of the Academy of Natural Sciences who currently serves as president of the council’s board, “We all got together every other month, as far as I could see, to kind of just complain about stuff.” The complaints were of the parochial nature you might expect from a bunch of museums: mostly annoyance at the frequent closures along the Parkway for events, which made it difficult for patrons to get to their destinations. (One person familiar with the Parkway Council of that era puts it a little more bluntly: “It was essentially a bitchfest by all the heads of the institutions. They didn’t like the noise, and all they cared about was getting cars to their garages.”)

Benjamin Franklin Parkway / Photograph by Steve Rosenbach/Getty Images

In early 2020, a few members of the Parkway Council started to contemplate a different way of doing business. Their relationship with City Hall, on account of the frequent griping, was “fractious,” according to Cooper. To have the heads of some of the most esteemed nonprofit institutions in Philadelphia assembling and not really doing anything felt like a waste. The idea, Cooper says, was to “toggle more towards being something where we could be more focused on all the positive things that we could do together.” After a bit of consideration, it became obvious that the council ought to build on “More Park, Less Way” and actually embark on a fundamental transformation of the Parkway — which would have the benefit of repairing the relationship with City Hall in the process.

The timing was ideal. Right around then, Ott Lovell, the Parks Commissioner, and Carroll, the OTIS deputy managing director, were beginning to have their own discussions about the Parkway. “There was this moment where all of a sudden, Kathryn’s energy, and the determination to really drive up the quality of the city’s parks, and the Parkway Council’s commitment to do its work differently came together,” Cooper says.

Perhaps most important, Carroll’s proposed redesign of the street at Eakins Oval unlocked the plan. “If you can’t solve the transportation component of this, then the plan kind of dies on the vine,” says Emily McCoy, an urban planner at Design Workshop. What had in past proposals amounted to a colossal infrastructure redesign was now achievable with much less disruption. “Psychologically and from a safety perspective, it’s huge,” Anderson says. “And then it kind of invites us to think about all of this space.” In 2021, the city released a request for proposals for the redesign; less than a year later, it selected Design Workshop. Now it fell to McCoy and her colleagues to repair a road that, as she puts it, “is a blank canvas of hostility — but one that has a lot of possibilities.”

There’s one hostility that won’t be going anywhere: the road itself. Although McCoy believes a full pedestrianization of the Parkway could be possible, Carroll says such a move was never seriously considered. “There’s neighborhoods that depend on those roads,” he says. “It’s not ‘All Park, No Way.’ It’s ‘Less Way.’” But it does raise a fundamental question: How much of a park is possible with a giant road still running through it? Matt Rader, the CEO of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society and past president of the Parkway Council, believes cars won’t feel as dominant as they do today. “You’re going to have a park at Eakins Oval, a park at Logan Square, and they’re going to be linked by two giant parks on both sides, and the cars in the middle are going to become almost irrelevant,” he says. “Whereas today it’s the opposite, because every space for people is just this little sliver of land between, like, two lanes of cars.” Anderson agrees. “Will it be bucolic, where you’re lost in nature? No. But can it be a vibrant urban park? That I think we can achieve.”

That transformation will take years. But the strength of the plan, Anderson believes, is in its melding of immediate and long-term initiatives. “We have the big vision, and then we have a very pragmatic first step,” he says. That first step — connecting the Art Museum to Eakins Oval — could begin as soon as 2026 and may take about five years. The Parkway Council is thinking about the project as a legacy of the country’s 250th anniversary, though construction wouldn’t begin until after the celebrations. It is an undeniably smart strategy. “We hope that will then create momentum that will then start to take a life of its own and make this inevitable,” Anderson says. “If you start to transform one segment and then it ends, people will say, ‘Well, wait, why can’t I keep walking? Why do I now hit this dead end?’” The Schuylkill River Trail, which has been assembled piece by piece over the past 30 years, is the Council’s oft-cited inspiration.

The city’s plans for the area between the Art Museum and Schuylkill, and Logan Circle. / Rendering by Design Workshop, courtesy of the Parkway Council

There remains one big hurdle for the future new Parkway: Who will pay for it? The city will cover the cost of the roadwork, thanks to the $23 million federal grant it got as part of the Biden infrastructure law. (According to Anderson, the city has yet to officially receive the money, but there has been no indication from the Trump administration that the funds are under threat.) It will fall to the Parkway Council to raise the rest of the funds — most likely from private foundations — to actually construct and landscape the $50 million park. That still leaves the proposed pedestrianization of Logan Circle and the connection of the new park to the Schuylkill River — two projects for which Anderson says it’s too early to provide cost estimates or timelines.

Fundraising to build and landscape the park is one thing; being able to keep it maintained is another. “I understand there’s a first step and they want to build consensus around what are very exciting ideas,” says Levy, the former Center City District president. “But to get funding, people are going to ask, ‘How are you going to maintain this?’” Levy points out that none of the parks the Center City District maintains — including Dilworth Park at City Hall and Sister Cities Park, which is located right off Logan Circle — pay for themselves. “Cafes help, sponsorships help, but you need a revenue source outside the park,” he says. In the Center City District’s case, that support comes from the mandatory fees all the properties in the district pay.

Rendering by Design Workshop, courtesy of the Parkway Council

There’s no such structure currently along the Parkway, and a tax solution could be challenging, considering that many of the buildings are owned by nonprofits. Levy believes development along the Parkway and taking a portion of rental income represents perhaps the best shot at revenue, although Anderson politely shoots down that idea. “There’s a strong feeling that public land needs to stay as such,” he says. Alternatively, the city could increase its Parks and Rec budget, or the Parkway Council could try to capture a chunk of the $43 million of new visitor spending it projects the new park will generate. But neither option seems especially likely. “It’s a very top-of-mind issue,” Anderson says of the funding challenge. “We frankly don’t yet have a full model for that. We’re exploring all sorts of ideas.”

As Anderson stands on the Parkway, he returns to the central idea — the one that, for all its ambition, is a much easier sell for now. “What I think we’ve hopefully found is an exciting, pretty fundamentally transformative change,” he says, “really shifting the balance from this feeling like major roadway with green spaces around it to a park that has a road.” As he speaks, a truck revs its engine, growling as it passes him by.

The Plan for the Parkway

The plan for Ben Franklin Parkway would turn 16 acres of pavement into green space, double the number of trees, and lead to a 53 percent increase in green or public space. Here’s how it would work.

Rendering by Design Workshop, courtesy of the Parkway Council

➊ Connect the Parkway to the Schuylkill • Currently cut off from the Art Museum by roads and on-ramps and overall poor design, the green space along the Schuylkill would be fully connected to the new park. Beyond new sports fields and festival spaces, the plan suggests the possibility of building a pedestrian bridge across the river to Schuylkill Yards and 30th Street Station.

➋ Connect Eakins Oval to the Art Museum • Removing the chaotic, clogged traffic lanes that currently separate the oval from the museum would not only improve safety but create a new park space at one of Philadelphia’s most visited destinations. Instead of idling tour buses, imagine a new public garden. Big improvement, right?

➌ Green the Parkway • The plan calls for the closure of the outer traffic lanes of the Parkway, converting the current lanes into green space. Traffic would be consolidated in the center lanes, and new pathways would be built for pedestrians, cyclists, and public transit. The new traffic pattern would include calming measures to cut down on illegal racing.

➍ Restore Logan Square • You take your life into your hands crossing Logan Circle right now. The plan calls for removing the traffic circle and stitching together Logan Square with nearby Sister Cities, Shakespeare, Pennypacker, and Aviator parks to create a public space unlike anything else in Philadelphia. This part of the plan also calls for capping a stretch of the Vine Street Expressway, which would bring the new space nearly to the front steps of the Parkway Central Library.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect who will be releasing the Design Workshop report this fall.

Published as “Benjamin Franklin Parkway” in the October 2025 issue of Philadelphia magazine.