Who, Exactly, Is Philly Fighting COVID?

How a 22-year-old CEO with virtually no health-care experience got picked to run the first mass vaccination clinic in Philadelphia.

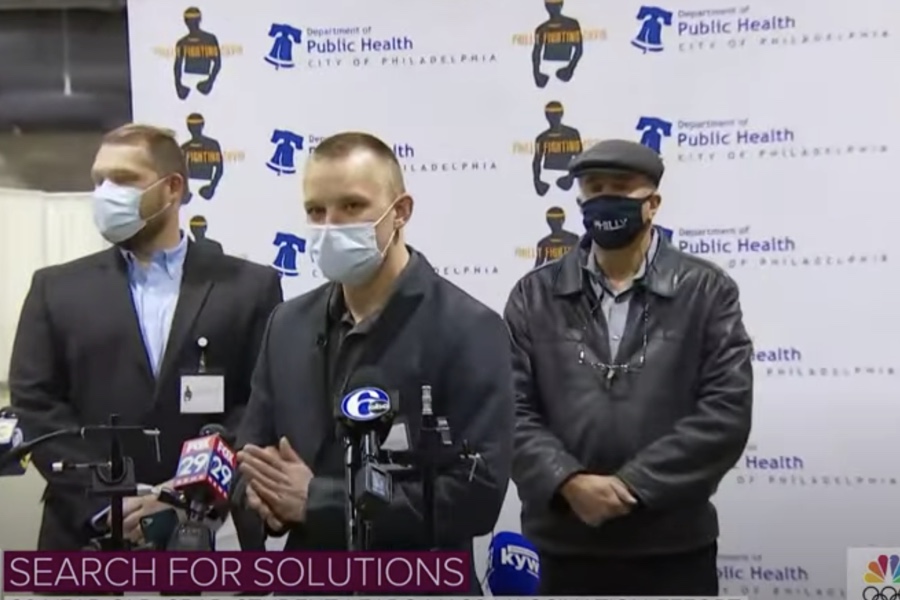

Philly Fighting COVID CEO Andrei Doroshin, center, pictured at a press conference for the city’s first mass vaccination clinic. Screenshot via YouTube.

Andrei Doroshin is 22 years old, working toward his degree at Drexel, and a C-suite executive in three different businesses: a real estate firm (CEO), a biotech company (CBO), and, most notably, an organization called Philly Fighting COVID (CEO). That’s the group that had been tapped by health officials to run Philadelphia’s first mass vaccination clinic. But just two and a half weeks after the first clinic went live, the city cut ties with them over concerns about its data privacy policy, its sudden shift to for-profit status, and its failure to maintain testing sites.

Doroshin formed Philly Fighting COVID during the early months of the pandemic, when he gathered a group of friends from Drexel to make face shields with 3-D printers and donate them to local hospitals. The group morphed into a pop-up COVID-19 testing center during the summer, then pivoted to its current iteration: vaccines. The organization, using doses provided by the city, has administered nearly 7,000 shots — about eight percent of Philly’s total first-dose count — to people at the Pennsylvania Convention Center. In the course of this progression, Doroshin has been hailed as a kind of operational savant.

“We took the entire model and just threw it out the window,” Doroshin said during a segment on the Today show earlier this month, explaining what he saw as his clinic’s two big innovations: getting rid of paper registrations and creating a vaccine assembly line to speed up the shot-giving process. “We think a little differently than people in health care do.”

But on Monday, the city department of health abruptly ended its relationship with Philly Fighting COVID, alleging that Doroshin turned the company into a for-profit entity behind its back and that the company changed the data privacy policy on its vaccine interest form, theoretically enabling it to sell user data — which includes names, ages, addresses and health conditions — to third parties.

“For Philly Fighting COVID to have made these changes without discussion with the city is extremely troubling,” a statement read. “As a result of these concerns, along with Philly Fighting COVID’s unexpected stoppage of testing operations, the health department has decided to stop providing vaccine to Philly Fighting COVID.”

Doroshin says he never sold and never will sell user data. He maintains that he directly informed Caroline Johnson, the city’s deputy health commissioner in charge of vaccine distribution, about the for-profit status prior to making the change. He claims he only turned Philly Fighting COVID into a for-profit to make it easier for the company to fund-raise and absorb the costs of running clinics. (A department spokesperson confirmed to the Inquirer that Doroshin told at least one city employee about becoming for-profit.)

“I don’t understand why people are freaking out about this kind of stuff,” he said this week — after the city first broke ties due to the user data and nonprofit status issues, but before he faced allegations of taking vaccine vials off-site. “We just vaccinated 2,000 more people this weekend. We only care about vaccinating people.”

Like many of the people who work for him at Philly Fighting COVID, Doroshin doesn’t have much health-care expertise. He’s in the fifth year of a combined undergrad/master’s psychology program, experience he readily admits isn’t germane to running health clinics.

Doroshin’s main qualification might have been that he’s audacious enough to suggest he’s qualified in the first place. There’s no denying his knack for salesmanship. His bio on the Philly Fighting COVID webpage states that he began his career as a director of photography for AND Productions in Los Angeles, formed and taught at the Rancho Mirage Film Department, then resigned to start a nonprofit focused on air pollution.

Left unsaid is the fact that AND Productions was founded by Doroshin’s father and appears to have no real online footprint. The YouTube channel for Doroshin’s other film project, a production company he founded called SpeedJumpFilms, includes one short film, along with videos of people longboarding and doing not-especially-impressive parkour routines. The Rancho Mirage Film Department was a high-school film class Doroshin helped teach while he was a student there, and the nonprofit he started, Invisible Sea, mostly consisted of a meme-heavy Twitter account, some minor community lobbying, and a fund-raiser with a $50,000 goal that netted $684. (“It didn’t do very well,” Doroshin says of the nonprofit. He also admits that his time at AND Productions — when he was a 14-year-old making short films with his dad — probably shouldn’t have been on his official bio. “I’m sorry about that,” he says.)

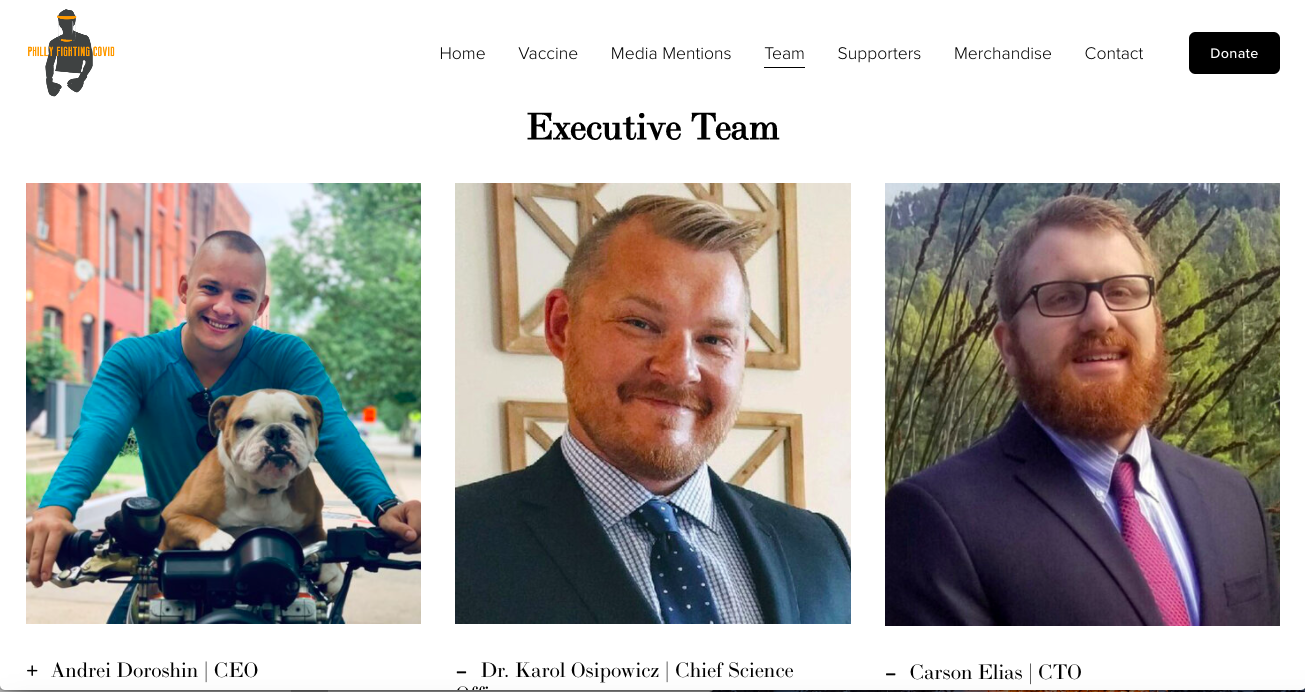

Other members of Philly Fighting COVID’s leadership don’t seem to have the qualifications typical of a group running a complex public-health operation, either. The group’s chief science officer is Karol Osipowicz, a Drexel neuroscience professor who also happens to be Doroshin’s academic adviser, not to mention a non-academic adviser to Doroshin’s real estate venture, Tala Resorts. In his official Philly Fighting COVID bio, Johnathan Lawless, the group’s “head of systems” (and the co-founder of the biotech company for which Doroshin moonlights as chief business officer), says he graduated from Drexel in 2019 with a bachelor’s in biomedical engineering and claims to have “played important roles at Johnson & Johnson,” though according to his LinkedIn profile, he only worked there for seven months while still in school.

No one on the group’s “executive team” boasts an advanced degree in public health or is an MD, though there are a few nurses and one doctor on the “operations team.” Many staffers appear to be in their 20s. And in a city that has struggled mightily to vaccinate Black people — a group that has received just 12 percent of all vaccines despite accounting for 44 percent of the population — everyone in a leadership position at Philly Fighting COVID is white. (Shortly after the city broke off its partnership with Philly Fighting COVID, the organization deleted its list of staff from its website, an action Doroshin says he took because staffers were being harassed.)

Doroshin insists that his background doesn’t really matter; when the government and health-care institutions were scrambling to respond to the pandemic, his group stepped up. “Our expertise is we’re just trying to help,” he says.

Part of the Philly Fighting COVID executive team, before the webpage was removed.

Philly Fighting COVID did demonstrate an ability to adapt and fill whatever COVID need was most pressing at a given time. Once the critical PPE shortage abated, Doroshin gathered a few more friends to “build out operations on what a testing clinic would look like.” He says he worked with Quest Diagnostics, which provided tests for free, and set up clinics throughout Philadelphia in underserved neighborhoods. Testing was slow at first — only a hundred or so people the first two weeks. Doroshin says he tried to partner with hospitals on testing clinics, but that “everybody kept saying no to us. So we said, ‘All right, we’ll just go and help the city.'”

The group applied for a city testing grant, and Doroshin says they received about $190,000 in funding. He claims Philly Fighting COVID ended up testing 20,000 people, 80 percent of whom were uninsured, and did so for $50,000 less than the grant amount. In an initial interview, he said he gave the city the rest of the money back.

But Jim Garrow, a health department spokesperson, says the city has paid Doroshin’s group only $111,000 for testing charges, in part because Philly Fighting COVID has submitted three separate invoices that were rejected “due to incomplete documentation and duplicative time sheets.” The time sheets showed employees working in two places at once, Garrow says. “These invoices were never resubmitted,” he says. “We will only pay out for legitimate costs incurred by the provider, as outlined in the contract.” Reached for comment yet again, Doroshin wrote in a text, “That’s correct.”

When it came time to begin vaccinations, Doroshin saw another opportunity, so he transformed Philly Fighting COVID once more, approaching the city in early January and offering to run a mass clinic for free.

In the United States, any organization that operates a clinic has to first submit a series of forms to the Centers for Disease Control, outlining, among other things, the physicians attached to the project and the qualifications of each person who will be administering shots. According to the health department, the paperwork and operational plan submitted by Doroshin’s group met all of the various state and federal requirements.

Whether the city fully vetted Doroshin’s résumé beyond that is unclear. But there’s one main reason the city selected Philly Fighting COVID to run its first vaccine clinic: “There was only one community provider that had finished their requisite forms and approvals and had come to us with a plan for how to distribute vaccine,” says Garrow. The city had no interest in turning away free help, and Doroshin was first in line. Within a week of reaching out, he was on the floor of the Convention Center, overseeing vaccinations to health-care workers in the city’s 1A group.

Meanwhile, Ala Stanford, who founded the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium and has been performing coronavirus tests in the Black community for months now, was waiting to begin vaccinations as well.

“If there was anybody poised and ready to do this, it was us,” says Stanford, who’s become one of the most visible doctors in the city during the pandemic. But even though she serves on the city’s vaccine advisory committee (alongside Doroshin, though Garrow told the Inquirer he would be removed) and is in near-constant contact with the health department, she says no one told her that Philly Fighting COVID would be the first group starting vaccinations. Instead, she found out from a news report. When she asked the city when her organization could begin receiving vaccine doses, she learned about the CDC’s paperwork requirements for what she says was the first time. (The city maintains that the vaccine application process was clearly posted online and communicated months ahead of time.)

Stanford says she had no problem with Philly Fighting COVID administering the 1A shots in theory; her plan was always to vaccinate community members — especially the Black Philadelphians who have been woefully underrepresented in receiving the vaccine — during the city’s 1B phase. But she was irked when someone from the city later reached out and proposed that she partner with Philly Fighting COVID on vaccinations, as if she couldn’t do it on her own. “We’ve been giving flu vaccine since October and doing COVID testing in the hardest-hit communities, and I happen to have been a doctor for 23 years, longer than some of these kids have been living, but I need these white kids to teach me how to do it?” Stanford recalls thinking. Mostly, she was frustrated at feeling like the city left her in the dark.

Prior to cutting ties with Doroshin, the health department maintained that everything at the Philly Fighting COVID clinic was running smoothly. Health department officials say they were on-site — as they are at every mass vaccination clinic — to keep watch over the vaccine, store it, and generally make sure nothing goes awry. “Ultimately, we have the control because we are the owners of the vaccine, and we manage the vaccine,” says deputy health commissioner Johnson.

But there were also signs that Philly Fighting COVID was starting to run into problems. When the city announced its own vaccine-interest website, the health department revealed that it didn’t actually have access to the data Doroshin’s group had accumulated on its separate interest website. WHYY reported that when Philly Fighting COVID began its vaccination operation, it abruptly suspended testing, abandoning community groups who relied on them for free tests. The organization told WHYY it stopped testing because of low demand.

Doroshin remains baffled that Philly Fighting COVID came under such a sudden attack. “We’ve done the job,” he claims. “We’ve delivered. That’s the crazy part. When somebody does the job and completes the contract, you don’t fire them; you say thank you.” (Garrow, the health department spokesperson, says Philly Fighting COVID has not actually fulfilled its COVID testing contract with the city.)

Doroshin disputes the allegation, made by one volunteer to WHYY, that Philly Fighting COVID leadership was bragging about becoming “millionaires” now that the company could bill insurance at least $18 per vaccine administered. He calls the idea that he was profiteering “crazy.” According to Doroshin, each day of running the vaccine clinic cost him between $20,000 and $50,000, what with paying for medical staff, the Convention Center space and other expenses. “I’ve got the same car I used to drive — I’m not running around in a Bentley,” he says. (Doroshin declined to provide expense documentation confirming the daily cost of the clinics.)

The allegations of a data privacy breach were equally “fabricated,” according to Doroshin; even if he wanted to sell personal data — which he insists he doesn’t — he says there would be no way to sell personal medical information, because it would be a HIPAA violation. (In fact, medical data is salable, so long as it’s anonymized.)

On Tuesday afternoon, yet another WHYY report contained an even more shocking allegation: One witness said she saw Doroshin take unused vaccines off-site following one of his clinics, and others reported seeing a photograph showing him standing before someone with a syringe in his hands, as if he was about to give a vaccination. At a press conference, health commissioner Thomas Farley confirmed that unused doses are expected to be returned to the health department.

Reached by text message, Doroshin responded to the allegations: “This is baseless, I have no idea why they are saying this.”

That same day, DA Larry Krasner and state attorney general Josh Shapiro asked anyone with information about Philly Fighting COVID’s involvement in potential crimes to contact them.

Having cut ties with the organization, the city now has to scramble to set up new clinics to ensure that those vaccinated by Doroshin’s group can get their second shots. The health department says it has no intention of providing Philly Fighting COVID with any vaccine again and that it doesn’t plan on renewing the group’s COVID testing contract, which is set to expire at the end of the month. But cutting ties at this point does little to answer the bigger question of how the city wound up in this mess in the first place.