One Month Inside a Philly Hospital on the Front Lines of the COVID-19 Pandemic

An unfiltered look inside the Einstein hospital system as the novel coronavirus swept through the city.

A look behind the scenes of Einstein Medical Center during the fight against the novel coronavirus. Photograph by Jeff Fusco

On Wednesday, March 11th, there were zero confirmed cases of coronavirus at Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia. There were zero confirmed cases of coronavirus at Einstein Medical Center in Montgomery County, and zero confirmed cases of coronavirus at Einstein Medical Center in Elkins Park. There were zero confirmed cases of coronavirus anywhere in the health system’s 11 outpatient clinics or among any of its 8,500 staff. In all of Philadelphia, there was just a single case.

But the leadership at Einstein knew those numbers would change soon. That same day, Barry Freedman, the institution’s chief executive, established what’s known as an “incident command center”: a group of employees whose job it would be to radically transform the operating procedures of the system’s hospitals in a matter of weeks to prepare for what every statistical modeling program and every medical expert considered to be an inevitable inundation of coronavirus patients. At the time, Freedman thought Einstein was ahead of the curve. Looking back a few weeks later, in early April, he realized he was wrong: “At the beginning, we mistakenly thought we had the luxury of time.”

By that point, the number of COVID-19 or suspected COVID-19 cases at Einstein’s hospitals had grown from zero to 200, taking up 25 percent of the system’s 753 beds. In those intervening weeks, administrators had been convening on twice-daily calls — one at 7:30 a.m., another at 5:30 p.m. — to chart the institution’s response. Among the changes made in that time: The health system canceled elective surgeries to clear extra bed space, and it determined which newly emptied wings of its hospitals could become coronavirus wards. It took a skill-set census of its doctors and nurses, so that if the institution ever had massive shortages in staff, it could tap, for instance, an orthopedic surgeon who had done a brief specialization in infectious disease during residency. Freedman and his staff also began tracking supplies of “personal protective equipment,” known by the now-ubiquitous acronym PPE, and monitoring the (often conflicting) medical guidance coming from groups like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization.

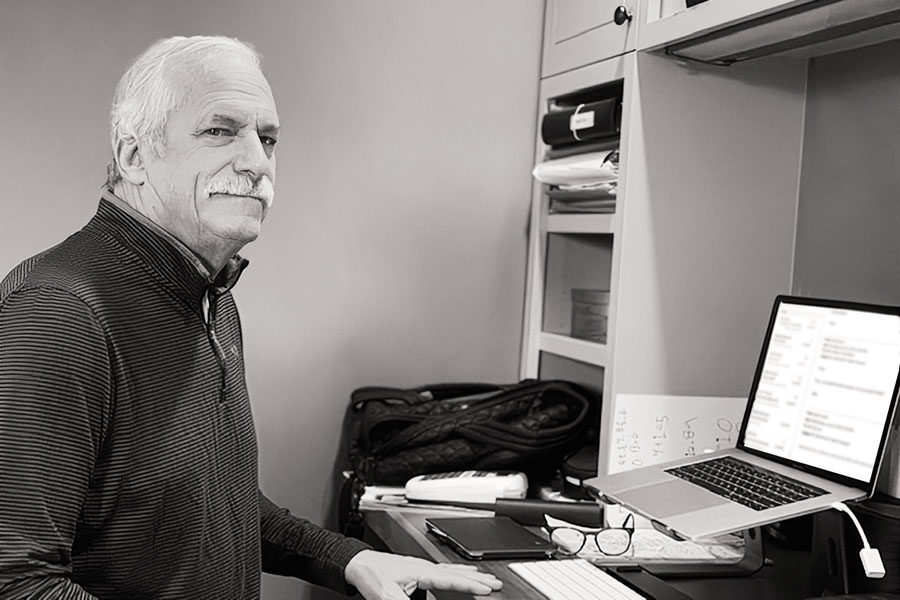

Freedman, who is 71 and has a chronic respiratory condition that left him hospitalized in the past year, was working from home on the order of his physician. He hadn’t been sleeping much, waking up every two hours in the middle of the night to check his phone and jot down woozy midnight ideas he could pass along at the next incident command meeting. When he and his staff first became aware of coronavirus back in January, the question they all tried to answer was: How can we avoid what’s going on in China? As the virus spread, the question mutated: How to avoid what was going on in Italy? Finally, it became: How to avoid what was going on in New York City?

Einstein CEO Barry Freedman.

What Einstein would go through over the course of a month — its preparation for a pandemic, the challenges its people faced as the cases grew — was by no means unique. Hospitals all over Philly, and throughout the rest of the country, were busy dealing with similar concerns. Transforming themselves. Planning. Tracking the various scenarios that suggested if — and when — they might run out of beds, or ventilators, or protective equipment. They all stood at the precipice of an outbreak, and when they peered over the edge, they could only see that there was a drop. How far was anyone’s guess.

In a sick person’s journey, the hospital is the final destination. That is to say, there’s only so much a hospital can do to prepare for a pandemic, because if a surge of patients arrives, society has already failed. A dispassionate auditor would likely identify no shortage of such failures in the U.S. when it came to coronavirus: a federal government that declined to take the risk seriously until it was too late; a nonexistent testing and contact-tracing system; an unregulated health-care supply chain that turned to price-gouging in times of crisis; a lack of societal buy-in among some people for social-distancing measures. For Einstein, it was like being the last player in a game of telephone — the one who has to guess the original phrase — when each person along the way was botching the answer, shifting the correct response a bit more each time.

So the best Einstein could do was wait. It could try to prepare for the worst. But all it could really do was wait.

March 16th

Confirmed COVID inpatients: 1

Suspected COVID inpatients: 0

Coordinating Einstein’s daily response to the pandemic was Ken Levitan, a 56-year-old who, on top of his usual job as chief administrative officer, assumed the rather soldierly title of “incident commander.” Levitan, who’d left Einstein after a decade to work in consulting and was now back for a second stint, was effectively responsible for directing the flows of bureaucratic traffic. “My primary goal is to make sure that the right people are talking to each other,” he told me.

In an institution with 8,500 employees, that meant plenty of phone calls, the most important of which were the twice-daily reports from the incident command team, comprised of some 40 people ranging from accounting staff to doctors, who occasionally called in to give updates in the middle of their shifts — their speech muffled by face masks and full PPE garb. The calls, which could last up to two hours, always began with an update tracking the virus in the Philadelphia region. On March 15th: 20 cases in Montgomery County, four in the City of Philadelphia — none yet at Einstein. At that point, Levitan was in command of a squadron still very much planning its defensive fortifications. The group discussed that day how it would develop an employee testing program, whether or not the hospitals should cancel elective surgeries, and which employees could work from home.

Two days later, there was progress. Einstein would transform two of its outpatient clinics in Philadelphia into ad hoc testing locations for employees and patients. Clinical staff had done an audit of hospital space and decided a wing on the sixth floor of Einstein’s Philadelphia hospital would act as a site for ICU patients in the event of an overflow at the regular ICU. “In a normal cadence, these things would take three months,” Levitan explained. “We got them done in less than a week.”

For all of Einstein’s maneuverings, it was a tall order for the methodical gears of a large institution — greased though they were through the streamlined incident command structure — to keep pace with a virus. By March 16th, four days after Einstein had its first incident command meeting, the Montgomery hospital confirmed its first positive COVID-19 diagnosis. The anticipatory period of planning was officially over.

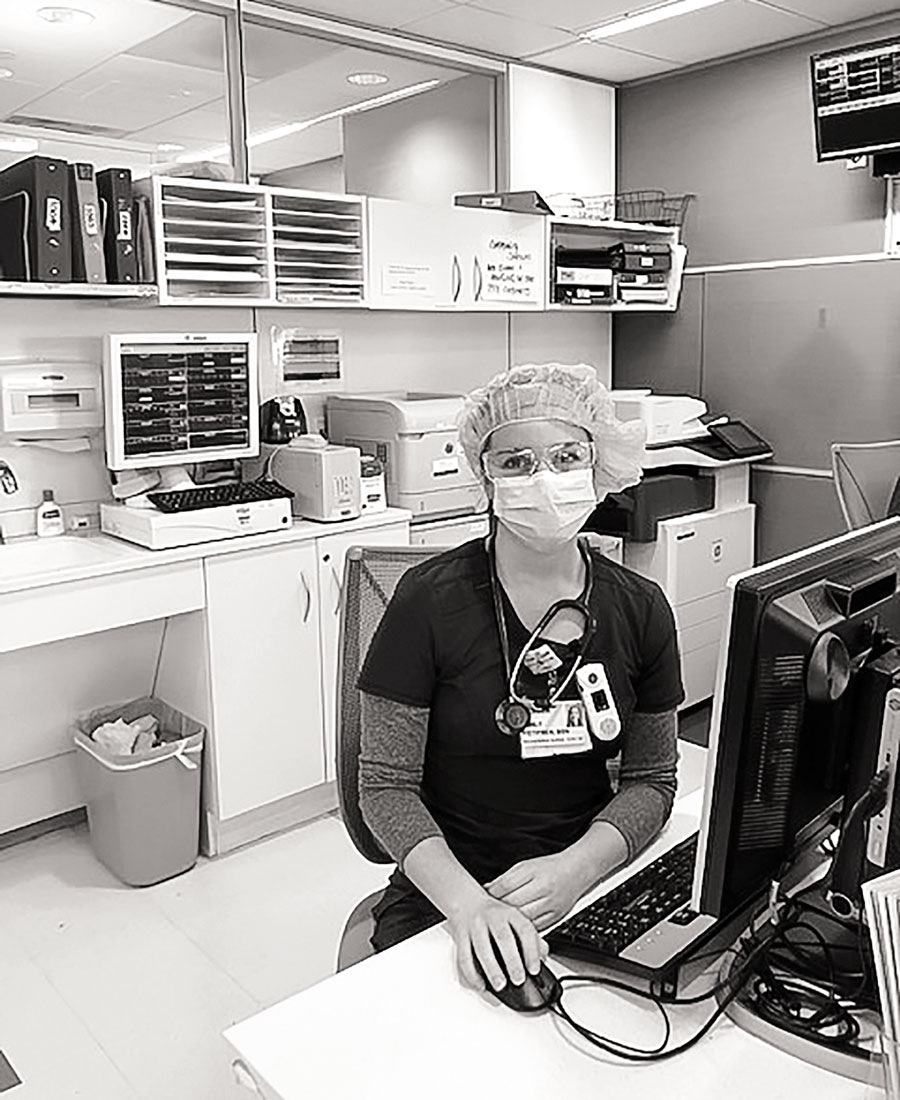

Nurse Emily Petipren.

Emily Petipren, a 26-year-old ICU nurse four years out of nursing school, was one of the primary care nurses for that patient, a man in his 40s who was physically active and had no underlying health problems. By the time Petipren saw him, he’d already been intubated — put to sleep and temporarily paralyzed so a doctor could guide a plastic tube down his throat, through his vocal cords, to block off his airway and attach the tube to a ventilator that would funnel oxygen directly into his lungs. Whatever Petipren had imagined her first COVID patient might look like, it wasn’t this. “You expect older patients — patients who have been smoking, who have COPD, asthma, who are already compromised,” she said. “But to have somebody come in with no health history — healthy, active person — and see them decompensate so quickly?” She only needed to see this once to realize: Whatever the coming weeks would hold, it was going to be bad — for patients and hospital staff alike.

There are more unknowns than knowns about how, exactly, the coronavirus sickens an individual, but what the doctors suspect is this: In the sickest patients, the virus attacks the lungs. The lungs, stressed and overwhelmed, begin to ooze fluid, which clogs the air sacs that deliver oxygen to the blood. Blood that lacks oxygen starts a chain reaction, crippling the rest of the organs. A healthy individual should have a blood oxygen level of 95 percent. In the coming days, Petipren would see coronavirus patients come into the hospital with oxygen levels anywhere between 20 and 60 percent.

There is no drug treatment for coronavirus. Doctors at Einstein would try prescribing the anti-malarial medication hydroxychloroquine, but absent a controlled study, there was no way to know whether a patient improved because of the drug — or in spite of it. As with many viruses, maddeningly, the only guaranteed method for helping a patient in serious distress was to keep him alive on a ventilator, leaving caregivers to watch, helplessly, as the body tried to combat the virus on its own. Sometimes, the lungs are so decimated, even a ventilator fails to oxygenate. The body suffocates.

March 25th

Confirmed COVID inpatients: 12

Suspected COVID inpatients: 105

Like most hospitals, Einstein had stockpiled personal protective equipment in case of a pandemic. Before this one began, the institution believed it had enough N95 respirator masks — critical pieces of equipment that filter out air and viral particles and provide the best protection for caregivers who have close contact with infectious patients — to last a year even under dire circumstances.

By late March, Einstein still had an enviable supply of N95 masks — though based on the new rate of consumption, they would last only a month, not a year. “The amount of PPE that we are blowing through on a daily basis — I never fathomed,” said Craig Sieving, the 49-year-old vice president of facilities who was tasked with procurement of all PPE during the pandemic. He added, “And it’s my job to think outside of the box of what’s going to happen.”

Sieving has worked at Einstein for 15 years. Prior to the pandemic, he coordinated logistics among various departments. Now, he developed a color-coded chart — green for adequate supply, yellow for a week’s worth, red for three days’ worth — to track the amount of PPE across Einstein’s three hospitals. By March 25th, the chart was beginning to display disconcerting splotches of yellow and red, particularly for surgical masks, which Einstein leadership mandated everyone in its hospitals wear. Weekly consumption of the masks jumped five-fold, to around 20,000.

In regular times, acquiring medical equipment for hospitals is relatively straightforward. But because the usual manufacturers of medical supplies were ill-prepared for the pandemic, there were now grotesque shortages. Einstein couldn’t request more masks from its PPE provider, because that supplier had to make sure all its other hospital clients received their predetermined allocations.

Meanwhile, it was impossible to predict what the federal government was going to do — or not do. A report by the Associated Press found that the federal government waited to place orders for N95 masks and ventilators until mid-March. Some hospitals discovered that orders they thought were confirmed were instead diverted to FEMA, without any explanation. When Pennsylvania requested some 500,000 N95 respirators from the government, it received less than 25 percent of the order. Einstein got a small shipment of N95s from the federal stockpile, only to find they were dry-rotted.

The collapse of the usual medical-supply marketplace generated a completely unregulated vacuum — one Sieving likened to a black market filled with opportunists. These new PPE suppliers weren’t part of the regular supply chain; they were businesspeople with connections (or alleged connections; scams were rampant, and Sieving was spending a not insignificant chunk of his time sussing out who was legit) to factories in China that could churn out PPE on short notice. They weren’t getting into the PPE business for humanitarian reasons; they simply knew the laws of economics: Low supply plus exceptionally high demand equals exceptionally high profits.

Vice president of facilities Craig Sieving.

The situation, Sieving said, had turned into a “mad scramble to go out and source additional supplies yourself,” with various hospital systems all competing for the same stock in the world’s highest-stakes eBay bidding war. Overnight, the price of surgical masks increased 20-fold, from five cents each to a dollar per mask. N95 respirators that once sold for a dollar now cost $8, if you could get them at all. “We’ve tried to purchase supplies at, say, 100,000 a clip, and we purchase them for $4,” Sieving said. “The next day, it’s like a commodity on the stock market: It’s going up to $4.50 or $5, and we’re getting orders canceled on us.” Sieving suspected other health systems were offering more money, and Einstein, already at a financial disadvantage as a safety-net hospital that doesn’t often bill private insurance, was getting priced out. (Between the inflated price of PPE and the canceled elective surgeries, the health system calculated that through June, it would take a $70 million hit to the bottom line.)

Einstein had already seen multiple “confirmed” orders evaporate. At one point, the hospital made a purchase of 5,000 face shields, but the day before they were to arrive, the shipment was cut to just 500. Similarly, in late March, Einstein’s surgical-mask supply was firmly in the red: only three days left. The hospital ordered 100,000 masks. Two days before delivery, the importer called to say the shipment was canceled. One Einstein employee was told the masks failed to pass inspection; another heard they’d been held up at customs in Mexico.

Sieving just figured he’d been outbid. “You’re completely powerless,” he said. “People’s lives are counting on this stuff, and suddenly somebody that you don’t know and don’t trust drops this bomb on you. It’s terrifying — but at same time, you want to throw your phone across the room.”

At times, Einstein explored procuring supplies through less conventional avenues. When the hospital was nearly out of the plastic single-use gowns that doctors and nurses wear over their scrubs, Barry Freedman, who has accumulated a hefty Rolodex of connections during his 48-year career in health care, spent the day calling in personal favors — emailing fellow hospital CEOs and leadership in Pennsylvania with an emergency plea for supplies. The ploy worked: Three different groups dispatched shipments.

Einstein also turned to DIY protective equipment. When it was short on face shields, Freedman told me, the children of an employee realized they could make them by attaching headbands to strips of mylar. This was cast as an inspirational story, though it’s hard not to see it in a more sinister light: A hospital is so short on PPE during a pandemic that it relies on enterprising children with headbands to make up the deficit.

While a global pandemic was perhaps always bound to be somewhat destabilizing, there’s a sense in which the COVID-19 virus was perfectly calibrated to exploit the co-morbidities of America’s supply chain. Because the virus presents symptoms that resemble those of the flu or a severe cold, when a patient showed up to Einstein emergency rooms with a cough — as happens thousands upon thousands of times each year during flu season — there was no way to rule out coronavirus. As a result, all health-care workers at the emergency departments had to assume the worst and wear N95 respirators as a precaution. Meanwhile, because it’s possible to spread coronavirus without displaying symptoms, everyone at the hospitals wore masks to prevent potential spread. And in what was a sick twist of karmic fate, it happened that two of the world’s production capitals for surgical masks and the swabs used for nasal testing were — wait for it — Hubei Province, China, where Wuhan is located, and Lombardy, Italy.

The shortage of coronavirus tests (which had less to do with Lombardy and more to do with the U.S. government’s utter lack of preparation for the virus) only complicated matters. Even in mid-March, Einstein was still sending its COVID tests to a lab in California — which had a backlog in the tens of thousands — and waiting a week to receive the results. Some 40 to 50 percent of inpatient tests were eventually coming back negative, but the staff had to keep waiting, and consuming scarce PPE, until the official clearance.

Eric Sachinwalla, an infectious disease doctor charged with coordinating Einstein’s medical response to the virus, explained that in some cases, the hospital had to keep caring for patients who otherwise might be healthy enough to be discharged to intermediate care facilities like nursing homes. But nursing homes, he said, which have been the site of half of all COVID-19 fatalities in Philadelphia, “don’t want to potentially bring in an infected patient that could create an outbreak.” Before accepting a patient discharge from Einstein, those facilities started to require two separate negative coronavirus tests.

The whole situation was one gigantic knot: The virus’s commonplace symptoms meant more PPE had to be consumed as a precaution. The inefficient testing indirectly consumed resources in the form of bed space and PPE. This helped to create an astronomical demand for that same PPE, which made it all the more impossible to attain. And the lack of PPE jeopardized the single most important resource any country has during a pandemic — and one that can’t be increased by invoking any federal manufacturing laws: the health of its caregivers.

April 2nd

Confirmed COVID inpatients: 39

Suspected COVID inpatients: 159

In early April, Einstein wasn’t yet at New York City levels of crisis. The ICUs in both the Philadelphia and Montgomery County locations were busy, but that was often true even during a regular flu season. Visits to the emergency room were actually lower than usual. While there was an influx of COVID patients, others with less severe cold or flu symptoms, who might normally have gone to the ER, had apparently decided to stay home.

When I received a virtual tour of the ICU at Einstein Montgomery over FaceTime (virtual because the hospital didn’t have any PPE to spare for a journalist), the strangest thing about the whole scene was how utterly normal everything seemed. AnnMarie Papa, the hospital’s chief nurse, wearing a blue surgical mask over her nose and mouth, a white coat, and glasses perched atop her head, walked me through the long, quiet hallways of the unit. A man wearing street clothes pushed a tall cart of food. Otherwise, the unit was mostly empty, save for the occasional gaggle of nurses — all in in navy scrubs, teal hair covers and face masks — who calmly huddled with doctors to discuss the prognoses of patients, waving as we passed by. Papa narrated the status quo as we walked: 17 of 22 ICU beds currently full; eight confirmed COVID cases, with another four suspected; all eight COVID cases on ventilators.

A health-care worker in the ICU.

There were only scattered signs of abnormality — the empty halls being one of them. Einstein had banned visitors. No exceptions. There were no children or spouses walking back and forth to relieve stress, no trips from the cafeteria to a patient’s room. When someone was dying, usually sedated and on a ventilator, families said their one-sided goodbyes via FaceTime, with a nurse holding a phone. On a wall at the edge of the barren hallway, staff had taped up messages from families that were a mix of well wishes and expressions of gratitude to the hospital staff. One of them, written in orange crayon and wobbly elementary-school handwriting, read, YOU SAVE LIVES.

Everyone wore a mask throughout the hospital — another sign of the times. Along the walls of the hallway, right next to the doors of the patient rooms, were row upon row of IV pumps and feeding tubes, the various curling connective wires snaking through cracks in the doorways. That way, nurses could perform many of their duties without actually entering the rooms. Less use of PPE for the hospital, but also longer periods of isolation for the patients.

Though the Einstein health system wasn’t yet overwhelmed, there were preliminary signs of stresses. “I’ve been a nurse for 45 years,” Papa said. “We have not ever lived through anything like this — and I’ve been through SARS, I’ve been through AIDS. It’s just so uncertain.” Part of the stress had its origin in materials, or lack thereof. In April, a respiratory therapist at Einstein Philadelphia issued a plea on Facebook for baby monitors: The hospital had run out of the high-tech rooms it normally uses for ventilated patients, and the new rooms didn’t have the proper alarms to signal ventilator problems.

Nurses were working their usual grueling 12-hour shifts, only now, once they got off the clock, there was little reprieve. Everyone knew and feared that this was a two-front battle — the virus could follow them home and infect their families. Many of the nurses choreographed post-shift detox routines to reduce the risk. Before returning home to Quakertown, where she lives with her husband, Emily Petipren — the ICU nurse who treated Einstein’s first COVID case — would change from her dirty scrubs into clean ones and sanitize her shoes, her badge, and even the pens she carries in her pocket. When she got home, she would leave her shoes outside the front door, throw both the clean scrubs and the dirty ones into the washing machine for multiple cycles, and head straight to the shower. “I act as if my house has the virus,” Petipren said. “My husband and I have quarantined ourselves from everybody else.”

April 8th

Confirmed COVID inpatients: 82

Suspected COVID inpatients: 138

Being hospitalized with coronavirus can be profoundly dehumanizing. You’re placed in a bed alone, without friends or family. Your only human contact, if it can be described as contact, is with doctors and nurses clothed in full-body suits that make them look more alien than human: flimsy cerulean ponchos that run to the shins, blue hair covers, shoe covers, clear plastic visors protecting their faces, white N95 respirators, purple gloves. As the patient, you must wear a mask when they enter your room.

Some patients started to crack under the circumstances. A woman in Petipren’s care started screaming, without a mask, at the nursing staff during her treatment. Other nurses, without time to put on their own masks and other PPE, had to rush to her room to subdue her. They may have been exposed to the virus as a result. Time will tell.

Another nurse, Dottie McBrien, who is 61 years old and has worked at Einstein for two decades, said patients she’d come to know well over the years had started to act differently. One of them, a middle-aged man who was staying on a fifth-floor cardiac ward that had been repurposed as an intermediate-severity coronavirus wing, woke up in the middle of the night and began ripping off his heart-monitor wires. “He was all over the bed, tossing and turning, pulling the sheets off,” McBrien said. The next morning, she spoke to him: The patient said he wasn’t sure what had happened. He thought he might have had a panic attack.

Nurses Dottie McBrien and Millie Yervell.

None of the nurses or doctors were afraid of the virus, really. Anyone who signs up to work in a hospital knows there will be infectious diseases. The fundamental source of fear was the unknowability of the next four weeks. The future, said Robert Fischer, chief of infectious diseases at Einstein Montgomery and Philadelphia, “is the specter that looms over every conversation.”

There were signs of a bleak future in the time machine of New York City. There, the outbreak was roughly two weeks ahead of the one in Philly, and caregivers had taken to wrapping their faces in bandannas and their bodies in garbage bags for lack of PPE. Some hospitals began sharing one respirator between multiple patients, which was, Fischer said, “the sort of thing that a year ago we would never have imagined in our wildest nightmares.” Though there were reasons to be optimistic — Philly implemented social distancing measures on the same day as New York, which in outbreak time meant the city was two weeks ahead — it was still too early to tell whether the scene 90 miles to the north was a nightmare or a premonition.

Even if Einstein did avoid a New York-level situation, there were mixed signals about whether conditions at its hospitals were deteriorating. Patient volumes had been increasing, and PPE regulations were shifting for the worse. In mid-March, Einstein told caregivers they would only receive two N95 masks per shift. In April, nurses started receiving just one. The masks were hot, skin-chafing, and hard to breathe in, and each time you took one off and put it back on — which the nurses typically did a few times per 12-hour shift, to eat and drink something — you risked exposure to the virus. To reuse an N95 like this, McBrien said, “throws every principle of infectious disease prevention out the window.” But other supplies were ample: The three Einstein hospitals had a total stock of 131 ventilators, and only 60 were in use.

Still, there was a sheen of foreboding among the front-line staff. They all seemed to know the latest predictions, which suggested, in early April, that Pennsylvania’s peak hospital volume would hit in two weeks’ time. The nurses were resigned to the fact that the worst was yet ahead.

“There’s a tsunami coming,” said Beth Duffy, Einstein Montgomery’s chief operating officer. Petipren described the present moment as “the calm before the storm.” In both metaphors, COVID was a natural disaster — an unstoppable and unpredictable incoming force. Einstein had brought in as many sandbags as it could find and boarded up as many windows as possible. The only question now was how bad the flood would be.

April 11th

Confirmed COVID inpatients: 106

Suspected COVID inpatients: 131

By the second week of April, one month after Barry Freedman had established the incident command center, Einstein was caring for 237 suspected or positive coronavirus patients. In the Philadelphia region, there had been more than 11,000 cases and more than 273 fatalities — 25 at Einstein. Still, the surge had not yet come.

There was a cruel irony. Of the patients to have fallen sick at Einstein, some were Einstein employees, including Jack Kelly, a 62-year-old emergency-room doctor. Back in February, Kelly had been scaling down in semi-retirement, working a few shifts per week. He knew he’d had contact with patients who had recently returned from Asia and Europe. At the time, Kelly was wearing only a surgical mask. Einstein leadership hadn’t yet created its incident command team, nor had it mandated that everyone in the ER wear an N95 mask.

On March 16th, Kelly started to feel sick. He had only body aches at first, and a temperature of 99 degrees. He stayed home, rested, and took Motrin. Kelly started feeling better, but he took a COVID test at an Einstein pop-up site, just in case. Then, on the 22nd, after six days of minimal symptoms, Kelly fell off a cliff: “It was like somebody flipped on this sudden switch and my whole body just said, ‘What?’” Out of nowhere, he developed debilitating shakes and chills. His wife, also a doctor, took him to the Einstein ER. Eventually, the diagnosis was confirmed: He was positive for COVID-19.

While any other person on Earth stricken with COVID pneumonia in both lungs, as Kelly was, would probably have checked into the hospital, he had just enough anti-hospitalization doctor pride to convince his colleagues to let him return home. Over the next few days, he checked his blood oxygen levels and temperature constantly. “Every afternoon, I had the worst shakes and rigors,” he said. “I had to get underneath five blankets and just shake for an hour until it stopped. The next seven days were pure suffering, night and day. It was just awful. The body aches, the fevers, the chills, the headache, and then the pneumonia portion … Every breath was work.”

Kelly was fortunate. Plenty of doctors and nurses had seen other seemingly healthy patients like him continue to deteriorate to the point where they could only breathe with the help of a ventilator. But by April, Kelly was recovering and through the worst. He’d recently reached a milestone: three consecutive days of no fever. He could officially break quarantine. His body remained withered and weak, though, and he planned to take the next few days to build up enough strength to be able to stand on his feet for eight hours — the basic requirement for completing a shift at the emergency department. He was already thinking about when he could go back to work.

On April 21st, Einstein was treating 176 confirmed and 63 suspected COVID inpatients; 198 COVID patients had been discharged, and 66 patients had died.

Published as “The Brink” in the May 2020 issue of Philadelphia magazine.