Ed Rendell Still Has a Few Things to Say

The former mayor and governor weighs in on his Parkinson’s, #MeToo, and where the Democratic Party lost its way.

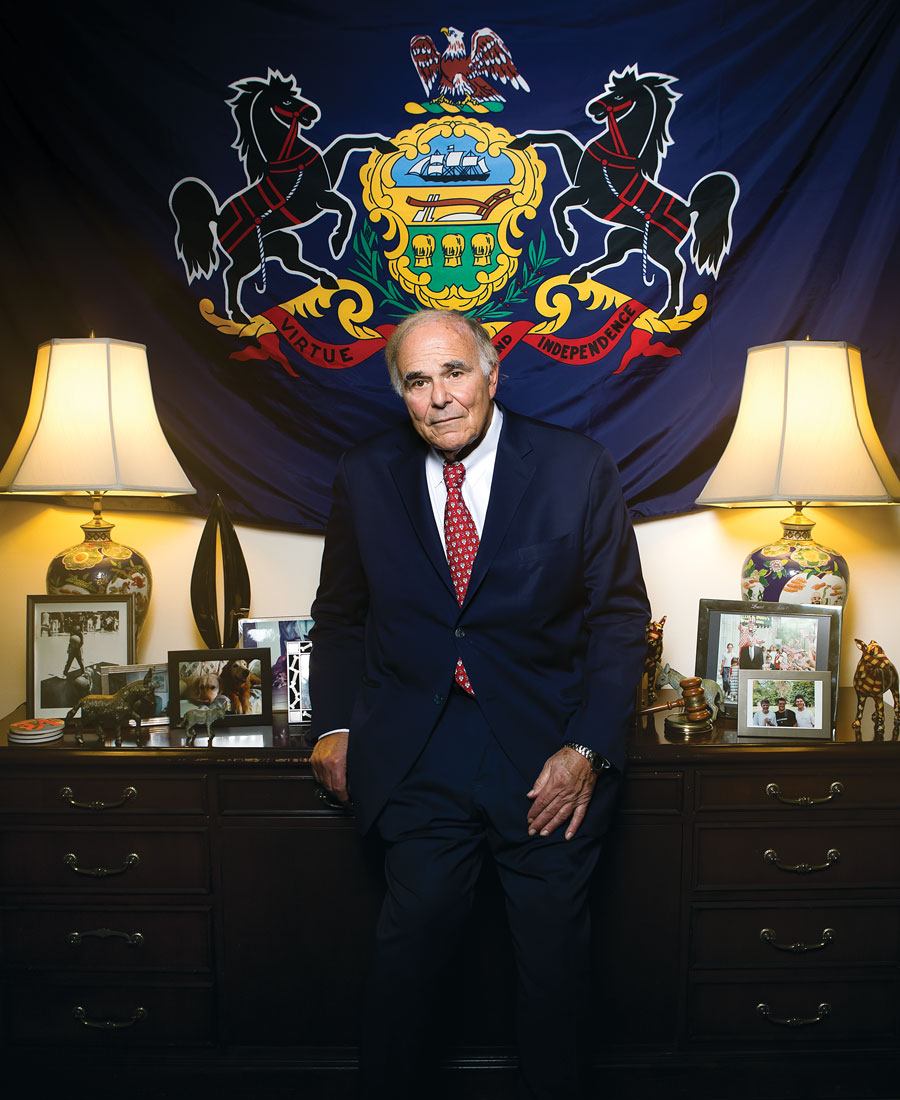

Ed Rendell in his office in the Bellevue. Photograph by Adam Jones

I begin to get, more than anything, worried.

I’ve been waiting outside Ed Rendell’s small stone Tudor in East Falls for him to answer the door.

I ring and knock; a dog barks and comes to the door, scratching. I wait a few minutes, and then the dog and I announce my presence again. Maybe I’ve got the wrong place, but there, just off the front patio, are two blue seats from Veterans Stadium, a firmer signal even than the address that this is Ed’s place. I know he’s ailing. Two years ago, Ed went public with his Parkinson’s diagnosis, which was a shock: the indestructible force and energy and optimism suddenly … sick. Old. I know he’s been in the hospital recently. I’ll wait.

I turn to admire the huge oak that towers over Ed’s small front yard, bare of leaves now, in January, and gaze across McMichael Park. That’s where Jesse, Ed’s son, and his daughter-in-law, Beka, and two young grandchildren live. Ed’s longtime wife, Midge, divorced him four years ago but still lived around the corner for a while, forming something of a compound — but she’s gone now, remarried, to a retired judge from Montgomery County, a Republican. A Trump supporter. Of all things, Midge, a federal judge herself, remarried to a Trumpster! Ed lives here alone.

Finally I call Trey, Ed’s assistant, at the Governor’s office downtown, and Trey assures me Ed is here, in the house, expecting me, though he isn’t answering Trey’s calls, either. Maybe he’s on the phone. Or …

Trey calls me back. The front door is unlocked. The Gov says to go right in.

I open the door. JC, a cocker spaniel/golden retriever mix, wags in friendliness.

“Governor?”

“Come in, Bob.”

A living room, dim. My eyes adjust. There he is, in a big armchair, lying almost on his side, away from me, where clearly he’s been for my 40 minutes of ringing and knocking and waiting, certainly in no condition to get up and answer the door. I get a chair from the dining room, sit before him, and Ed Rendell immediately starts talking once I ask the obvious question: “How are you?”

“I’ve got Parkinson’s, it’s degenerative,” he says. “Sure, and so is old age.” Ed smiles. “My knees and back are starting to kill me, but my Parkinson’s bothers me very little — some balance issues, not much. No aches and pains from it.”

Ed holds his left hand out. One of the symptoms of Parkinson’s is shakiness; his hand wobbles just slightly. “This house has a modern kitchen, except there’s no ice maker. I pride myself: I can fill four ice trays from the sink and take them to the freezer without spilling a drop.”

Ed’s wearing a dark sweatshirt and dark pants and bright yellow socks, with strap-over Velcro shoes. Remember those photos of George Bush the elder, toward the end of his life, in a wheelchair, seeming always to be wearing bright red socks? That’s what Ed’s yellow socks, with some white decorative business on the sides, remind me of.

He’s like an uncle you haven’t seen for a long time, and the change is surprising, though not to him — he’s been living it. And despite my long wait outside that neither of us mentions, Ed lets me in to his life fast.

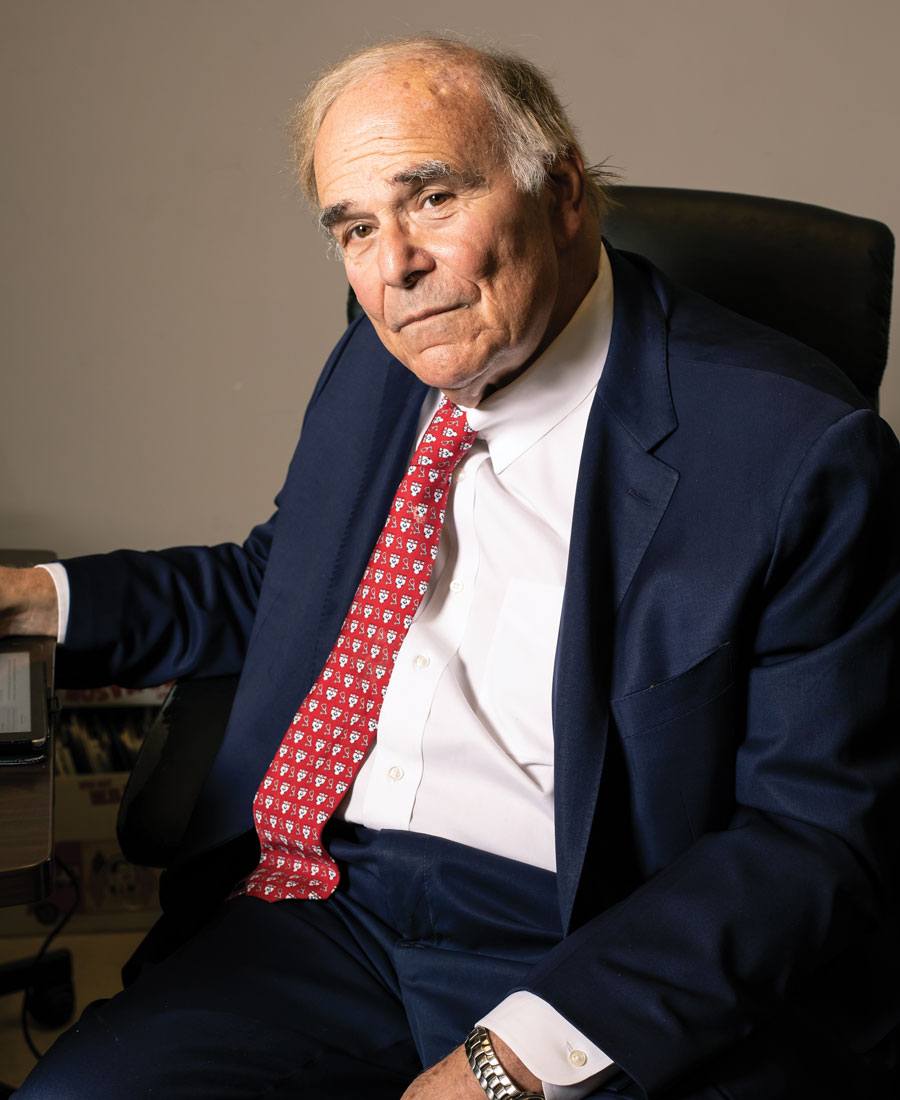

“My knees and back are starting to kill me,” Ed Rendell says, “but my Parkinson’s bothers me very little.” Photograph by Adam Jones

While he’s generally more mobile than how I’ve found him, Ed has an extra vertebra in his back, which has always given him some problems and lately has flared up big-time. He got an MRI on Christmas Eve and was holed up at home — except for getting driven downtown to appear on two Eagles post-game shows — until the new year. He’s taking an opioid for the pain now, and he says he understands how people get addicted to them. In December, he spent some time in the hospital for a mysterious blood infection that occasionally shows up in his legs; he now takes a daily dose of penicillin to ward that off. “I went 70 years without having serious health problems — a few hernia operations, one infected elbow, but I never missed work. Now, the last five years, a ton of stuff.”

Ed keeps talking in the quiet light of late afternoon.

Raising money for Parkinson’s research — “That seems to be my lot. I get Parkinson’s and end up raising money. It never ends” — segues into wanting to give his own money away, which raises the question (to him, anyway) of how his life is different now that he’s out of public service. It isn’t, Ed claims, except he has more money, which lets him eat out more and give money away. He loves eating out. He’s in a little movie club that goes to dinner and a movie every 10 days or so, and when he goes out, people are wonderful to him, though the bane of his existence is everyone wanting to take his picture, which leads, naturally, to Susan. “I haven’t really dated seriously since Midge and I separated,” he says. Susan is a good friend he was seeing semi-regularly, until she moved to North Carolina to be closer to her daughters. One night when he was out with her, someone wanted to take her picture because she looks like Carly Simon, whom Ed just happened to go to high school with in New York. Once, when he was mayor, Ed was in L.A., trying to convince the House of Blues owner to open one in Philly, and playing that night was … Carly Simon. Ed got word to her that he was in the audience: “She said, ‘We have a special guest tonight — he was a football player, I was a cheerleader.’ Now, I was a marginal player at best, and she wouldn’t have been caught dead in a cheerleader’s uniform. She dedicated a song, ‘Nobody Does It Better.’ I thought, thank God this isn’t in Philadelphia. I would have been fried.”

Which leads, in turn, to our president: “Though Donald has changed all the rules. The famous tape” — where Trump was caught bragging about grabbing women’s genitals — “he just denies that he said those things. He just denies!” Ed can’t stand Trump, but he does seem to hold a certain admiration for his audacity. The two go way back, I now learn. Trump wooed Ed with $50,000 in campaign contributions when he ran for governor in 2002, hoping to get in on Ed’s push for casinos in Pennsylvania, and Ed and Midge attended Donald’s wedding to Melania in ’05 at Mar-a-Lago, but things grew frosty when Trump put in a bid for a casino in Nicetown that he didn’t get. In fact, Ed knew just who he was dealing with, from the first time he met Trump, in New York when he was running for mayor in 1991. Ed’s buddy, the late businessman Lew Katz, took him to a fund-raising breakfast in New York to meet five real estate developers, and Trump came in last, brandishing Polaroids of the woman he had just spent the night with in various states of undress. “I thought, ‘This guy is crazy,’” Ed says. “Would you show them to the guy who might become mayor of Philadelphia? Would that be the impression you want to make?”

Ed went to New York to meet five real estate developers. Trump came in last, brandishing Polaroids of the woman he had just spent the night with in various states of undress. “I thought, ‘This guy is crazy,’” Ed says.

Whew. From death’s door to the trade winds of high-level gossip — we’re half an hour in, Ed Rendell and me, and I’ve yet to ask a question beyond that initial “How are you?”

Trump begat the current political atmosphere, of course. Ed supports Joe Biden. In fact, he claims a sort of ownership of Biden, saying he was the first to suggest him as running mate for Barack Obama in 2008.

Ed Rendell will talk, over three long conversations on three days at his house, about all kinds of things. After holding office for 24 years — eight-year runs as DA of this city, then as mayor, then governor — he’s well into the new stage of being on his own.

When he left Harrisburg and came home to Philly for good in 2011, with an office in the Bellevue, Ed would say, for a year or more, “It’s not the same.” As if he was mourning the loss of something special, and he was: his place at the center of the action.

He’s past that now. Ed is 76 years old, and the physical plant seems to be falling apart. He lives with JC and Royal, a 10-year-old golden retriever he rescued to a life of leisure after she birthed some 60 puppies; she barely stirs from her bed in the middle of the living room, which is decorated in Late American Ed, with a tan couch and armchairs brought home from the governor’s mansion in Harrisburg. His life is different. But Ed Rendell still has his finger on our national conversation.

In fact, the shift isn’t so much being out of the action — supporting Joe Biden (and attacking Elizabeth Warren, as Ed recently did in an op-ed in the Washington Post) places him squarely in the warpath of the progressive wing of his party. Which is fine by Ed, since he’s only too happy to defend his guy and their mutual methods. “If people say, ‘You often acted like a politician,’ well, sure,” Ed says, smiling at how simple, and obvious, this is. “But politicians are the only ones who get things done. Idealists don’t get things done.”

What’s at stake now, in other words, gives him a chance to keep talking. Not that Ed Rendell needs any prodding.

He knew full well what he was confronting when he ran for mayor in 1991: the worst financial crisis in the history of the city, what could have turned out to be a budget overrun for the next five years of more than $1 billion. In fact, Ed knew what the city was facing back in ’87, when he broke a promise he’d made to black ministers not to run for mayor against Wilson Goode. But nobody wanted to talk money problems then; that Democratic primary was all about the MOVE bombing. Ed lost.

And Ed himself was lost. After two terms as DA, he came up short in primaries for governor and then against Goode — Rendell was unfocused, a standard liberal Democrat. It seems strange now, but he lacked passion. He was considered slick, dubbed “Fast Eddie,” and hadn’t even been invited to the Democratic National Convention as a delegate in 1988.

Ed considered a run for attorney general. David Cohen, then a young lawyer at Ballard, had gotten to know Ed and remembers asking him: “Do you really want to be attorney general?”

“No.”

“Then why would you run for it?”

It was a low point. Ed had gone into private practice, repping asbestos companies. Cohen suggested another run for mayor. And as political consultant Neil Oxman would note in A Prayer for the City, Buzz Bissinger’s account of the early days of Rendell’s mayoralty: “Somehow, he woke up in 1990 and said, ‘I’m going to do this the right way.’”

Ed and Cohen would spend two and a half years going to various cities, talking to mayors to get ideas. So what changed him?

“Losing,” Ed says. “It’s interesting. Almost everyone who runs, and great athletes, should experience defeat. You don’t realize how hard it is. It’s physically brutal.”

He and Cohen went to see Mayor Ed Koch in New York. Ed knew him a bit from his time as DA, and Koch knew he was Jewish, so he wanted to help, Ed says. And when Koch found out that Ed had actually read a 1,000-page report on New York’s finances, “He was really anxious to help us. He said we were one of five people who actually read it.” Ed’s wonky side is a tender point of pride with him, especially in light of those first few years he was mayor, when Cohen became famous for more or less running everything. Not so, says Ed. In fact, most of the ideas were generated by him.

It’s an oft-told story: how in 1992, Ed Rendell (and Cohen) took on the municipal unions, which were threatening a strike that would cripple the city and ruin Ed right out of the gate. He sold his bargaining position every chance he got to a public well aware the city was financially destitute. A go-to Rendell jab: 12 paid city holidays were too many, and “perhaps city workers could overcome the emotional distress of working Flag Day.” Naturally, the workers pushed back: One day, union picketers severely beat up a guy who broke their line to deliver a message to City Hall, and Ed saw red when the cops, in solidarity, looked the other way: “The union would have to kill that guy [for the cops] to make an arrest. They broke his ribs, and nobody made an arrest. I just went nuts. Part of it was acting, but I’m not that good an actor. I felt it inside me. I wanted to say to each of those commanders: How can you fucking sleep at night?” Fast Eddie had found his cause.

Trouble loomed for months. Picketers rocked his car a few times outside City Hall, which he says didn’t bother him; he’d gotten threats when he was DA. Eventually, after a 16-hour strike, he got his deal with the unions; disaster — “We would have been Detroit without the cars,” Rendell says — was averted.

Yet there was something else wrong, maybe even worse: a cancer gnawing at the city, deep and growing. “We were dying, not just substantively, but our spirit was stripped away from us,” Ed says. “No one believed in us, that Philly could be a great city again.”

There was no denying the force of his cheerleading — the Ed of jumping into city pools and showing up, it seemed, at every new Wawa opening, and talking up his city every chance he got.

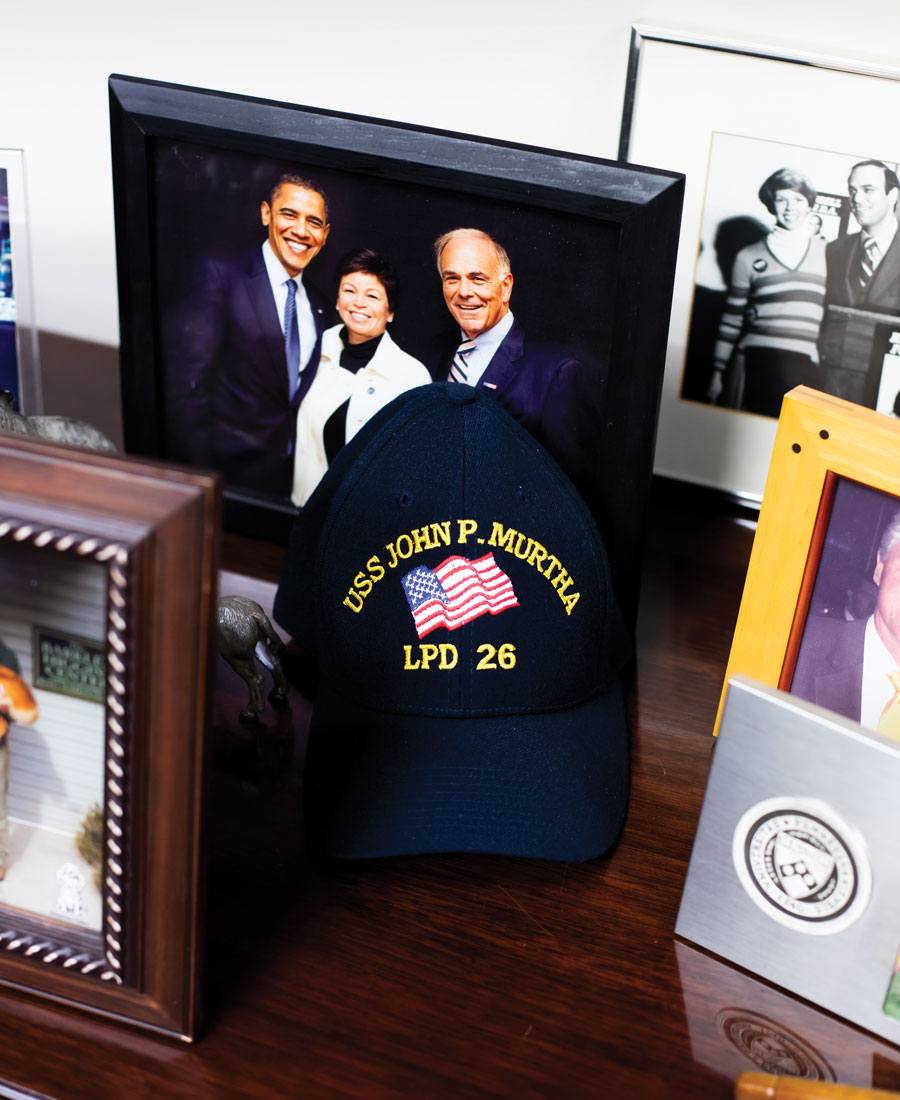

Career mementos in Rendell’s office. Photograph by Adam Jones

Ed Rendell had always craved attention, and here he was, front and center, solving the city’s biggest crisis ever and selling Philadelphia to the world. He got anointed America’s Mayor, and at the same time largely took a pass on other huge problems, such as education and policing. There’s a school of thought that losing his father to a heart attack when he was 14 stunted Ed’s emotional growth, that his lust for attention, not to mention for pleasing people — Vince Fumo still complains that behind closed doors, Rendell would promise the world to anyone — is the mark of a truncated psyche. As if Ed, in cheerleading for Philadelphia, was just being Ed.

Which does him an injustice: The public was invited to take part in a cleanup of City Hall one Saturday the first month Ed was mayor, and he found himself on his hands and knees, scrubbing away next to a woman who had driven with her young family from Altoona. From Altoona! She had grown up in South Philly and talked about her childhood in the neighborhood, how much it had meant to her, and here she was, with her kids, putting in a day of scrubbing City Hall and then driving back home to Altoona.

Ed tells me that story and, still lying half on his side in his dim living room, is suddenly almost yelling at the memory, of how moved he was: “If she cared that much … ”

“It’s pretty clear to me he took over a city that had stopped believing in itself,” Sam Katz says when I ask him what Ed’s legacy is. Katz, who has known Ed for 45 years, ran for mayor himself three times. “The city had lost its appetite for self-enthusiasm. And I think he fairly reversed that.

“One hundred years from now, we won’t know why Philadelphia is doing well, but it will be because Philadelphia pivoted away from doing bad things.”

That pivot, what David Cohen calls “trying to turn an aircraft carrier around in the Delaware,” is Ed’s legacy as mayor.

He’s a funny guy, though, to think of as a statesman. When I do ask him about his father, for example, to tell me what it was like to lose him so early …

“Horrible.” His voice is a low growl, and he repeats just that word: “Horrible.” Quickly, his thoughts turn: “When Lew Katz died [in 2014], the one thing I was sure of was that life wouldn’t be as much fun anymore. Even serious business, he was fun. He had a great sense of humor. The night of my farewell dinner as mayor, which was just an excuse to have a fund-raiser for governor, he and I were waiting for Bill Clinton, coming from a trade conference in Seattle. He came in, beat to shit. He saw Lew and brightened up and said, ‘I’ve got a joke to tell you. What do a man crossing the Grand Canyon on a high wire and a man getting blown by an 80-year-old woman — what advice would you give them, the same advice?’ Lew and I looked at each other. ‘Don’t look down,’ Clinton said.”

I ask Ed Rendell how Bill Clinton is doing.

“He’s not a happy guy. He really wanted Hillary to win. He wanted Hillary to win more than she wanted to win, I think. Bill doesn’t feel relevant.”

Ed calls it his “ejecto chair.” His armchair is motorized, with a back that propels forward to help launch him upright; his knees and back make getting there tough. And walking: Because of that extra vertebra, and degeneration, he appears to be battling a stiff wind as he tries to walk, buffeted against the wall of his living room for support. It looks really painful.

The second day we talk, he sits at his desk at the rear of his house, a big picture window looking out into his small backyard. Ed’s eating some sort of fish and egg concoction out of a bowl with his fingers; some of it dribbles onto his chin. And he’s wearing, I think, the same pants and shirt as three days earlier; his socks are still bright yellow.

I tell him I have a dumb observation: He looks tan.

Ed brightens.

“When I’m mobile, even in the cold, I’ll put on a jacket, take a book, take Royal and JC, and sit in the sun. Since I’ve been somewhat incapacitated, this window — I realized it doesn’t screen out all the sun. In December and January, I get sun from 10 till about 1:30. Come February, 11 to 2:30. I sit here in the morning and do work.

“There’s a great Beach Boys song — okay, Google, play ‘Warmth of the Sun’ by the Beach Boys.”

We’re serenaded.

“Such a beautiful singing group, so sad what happened to them. Okay, Google, stop.”

I remember reading something about his ability to have off-the-wall fun: that when he was DA — Ed served from 1978 to ’85 — he’d get rid of guests at office parties at his apartment by serving them dog food with mayo.

“Yeah,” Ed says. “The funny part was, they were all so drunk, they said, ‘This is good.’”

I ask him about current DA Larry Krasner. Ed isn’t a fan. Ed instituted the first rape crisis and police brutality units in the office, which would fit with Krasner’s progressiveness. Ed also instituted a tough policy on career criminals; Krasner, of course, has taken praise and heat for being criminal-friendly. I suggest to Ed that his politics, too, would have seemed more closely aligned with a stint in the public defender’s office.

“It’s funny,” Ed says, “but after six months on the job [as a prosecutor in the DA’s office under Arlen Specter, who hired him out of Villanova law school], we’d get together, myself and my law-school classmates, and they’d say, ‘How can you do your job, putting poor people in jail all day?’ I’d tell them, ‘You guys have it wrong. We are repping people’” — he means crime victims — “‘who have never had a champion in their entire life. Their entire life, nobody has ever spoken for them.’ And Arlen’s view was, we were the only thing keeping the city from slipping through the gates of Hell.”

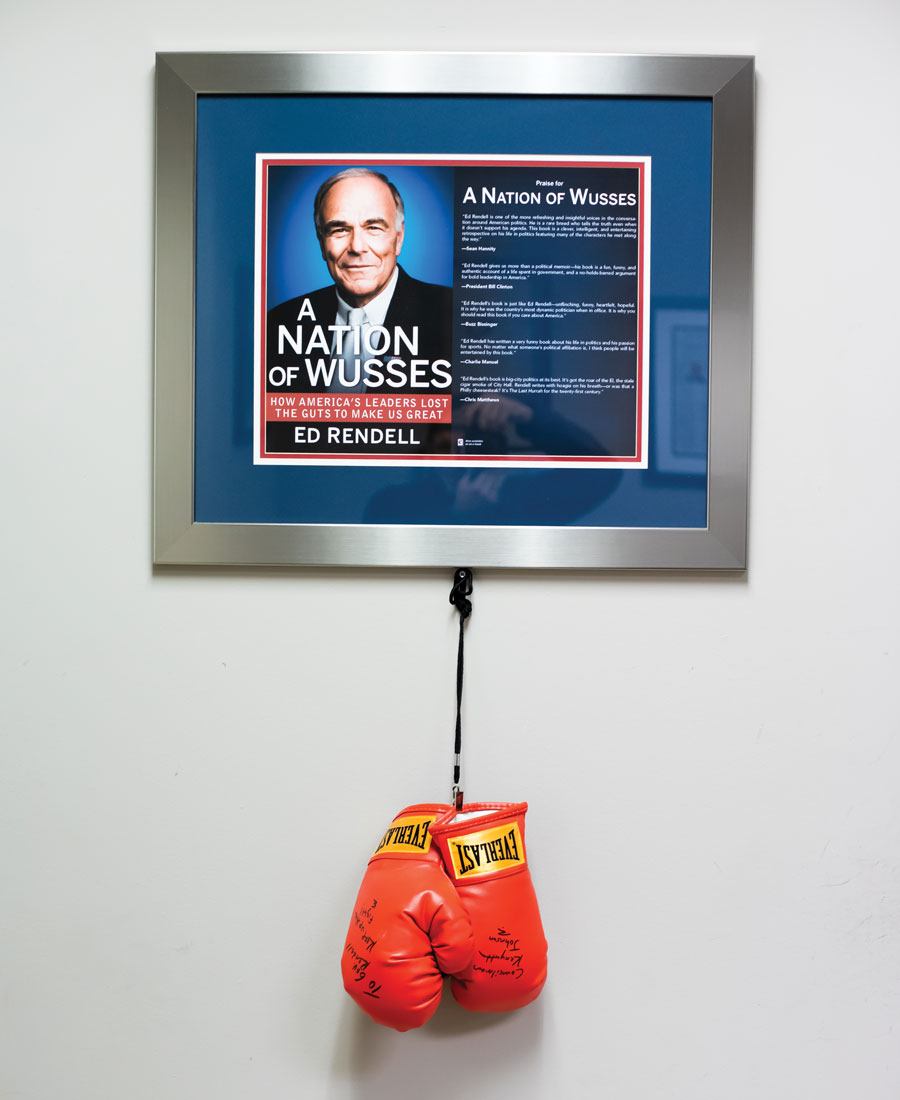

A Nation of Wusses was published in 2012. Photograph by Adam Jones

When I ask ex-state senator Vince Fumo how hard Ed pushed for prison sentences while he was DA, Fumo places him somewhere between Krasner and longtime DA Lynne Abraham, who was notoriously aggressive in pursuing long sentences.

“I was probably a little closer to Lynne,” Ed says. “If the distance between them is 100, I was 35 away from Lynne, 65 away from Larry. He has never called me and asked for advice. I think I called him once. Victims in 98 percent of crimes are poor people. Rittenhouse Square is victimized in two percent of crimes — Larry doesn’t grasp that. And you can do both!” That is, go hard after career criminals and treat defendants fairly.

“The toughest crimes to prosecute in those days were victimless. If cops found someone selling two bags of marijuana, Arlen wanted us to get a jail sentence. To what end?”

There was always deal-making, too, the nature of the game. Ed would, in fact, become a master of hardball politics as mayor, wheeling and dealing with John Street and Vince Fumo and John Dougherty, just the sort of old-school players the progressive wing of his party now wants dead and buried. I challenge Ed on how he justified working with Dougherty back in the ’90s. “Nobody is all good or all bad,” he says. “John and the [electricians] union were very helpful in getting things Philly needed. Now, it might have been in their self-interest, but it gave us political clout in Harrisburg we wouldn’t have had on our own. That’s why a lot of well-intentioned progressives don’t get stuff done. You take your allies where you find them.”

And you make deals: As mayor, with a strike of municipal workers looming in that summer of 1992, Ed wrote a secret letter, never to be made public, assuring Jim Sutton, the head of the union representing most of the city’s blue-collar workforce, that the city would not privatize trash collection; that got Ed and his team over the hump in negotiations. In 2009, during intense budget negotiations with the General Assembly when Ed was governor, Republican Senator Joe Scarnati asked to see him privately. Scarnati showed the Governor a yellow piece of paper that listed nine projects he wanted done in his district in central Pennsylvania. If Ed said yes to them, Scarnati would get Ed’s budget passed.

“Now, would Elizabeth Warren have done that?” Ed says. “She would have tried to have Scarnati arrested. And yet a $27 billion budget was passed. Which gave an extra billion dollars to schoolkids.”

The light coming in Ed’s rear window, highlighting his tan, seems to melt away the years. Ed loves talking politics, and he is certainly unapologetic about his methods.

Ed is honest, too, about an energy he couldn’t quite seem to control, his personal comportment. In A Prayer for the City, Buzz Bissinger wrote: “He was the embodiment of a public man, utterly defined by his place in the public eye and the way the public reacted to him, and the private acts that usually define a life — family, friendships, religious faith — seemed of little sustaining moment to him.”

I wrote a piece about Ed Rendell a decade ago that wondered aloud whether he was having an affair, while he was governor, with a state media-relations employee named Kirstin Snow, a Miss Pennsylvania who was accompanying him to events to, among other things, clean his tie with baby wipes, given the inevitable entrails of finger-food meals left behind. Though both denied having an affair, the publicness of the piece, Ed has claimed, triggered Midge to divorce him.

I thank him now for talking to me despite that fallout.

“You know what?” he says. “I’ve lived a charmed life, but you can’t escape forever. Your misdeeds will eventually catch up with you.” He seems almost wistful in speaking generally about his past, an unusual emotion for him. “But that’s another story.”

I ask Ed for his take on the #MeToo movement.

“What got me about it is that there is no discernment — they treated Matt Lauer, who raped a girl in his hotel room, the same as Al Franken, which is ridiculous. There are degrees of wrongdoing.” Franken, a Minnesota senator, resigned in 2018 after accusations of sexual impropriety. “What Franken did wrong, he shouldn’t have resigned. He should have just said censure me, and taken his case to voters. That would have been a lot smarter. If Franken was guilty of everything they said he was, he should not have been thrown out. He touched a few rear ends, and there was the picture of him that caused the big hullabaloo.” In the photo, taken during a USO tour in the Middle East in 2006, Franken mugs as he gropes a fellow performer while she sleeps.

“What got me about it is that there is no discernment,” Ed says of the #MeToo movement. “They treated Matt Lauer, who raped a girl in his hotel room, the same as Al Franken, which is ridiculous. There are degrees of wrongdoing.”

I wonder if the #MeToo movement would be a problem for Ed if he were in office now.

“I was always pretty good at knowing the rules,” he says. “If I got elected mayor tomorrow, I wouldn’t tell a dirty joke. It was mostly older, unattractive women, I’d say, ‘Dear, that’s a lovely blouse you’re wearing.’ Because it made them feel good! But I wouldn’t dare say that today.

“The thing is,” he goes on, “I like women of all stripes. My movie club is myself and five women. Except for sports, I have much more in common with women than men. Midge always said that I have a strong feminine side.

“The thing that I worried about, though not enough to change my behavior,” Ed says, “was it getting public and embarrassing Midge.”

“My movie club is myself and five women,” Ed says. “Except for sports, I have much more in common with women than men. Midge always said that I have a strong feminine side.”

The personal, of course, has become highly political, especially in the progressive wing of Ed’s party. Talking about women, and Midge, can make him seem a bit lost to this moment. And terribly lonely, which he claims he would be if he didn’t have his dogs to come home to.

Ed is certainly busy, though, and it doesn’t present as the busyness of someone trying hard (or too hard) to remain engaged. He’s on the boards of half a dozen companies — including Public Financial Management, American Security and Learning Care (a child-care company) — and another half dozen nonprofits, including the Constitution Center and Building America’s Future. He gets paid $300,000 a year by Ballard Spahr as a rainmaking attorney (spending maybe one day a week in the office), and his overall income, bolstered by TV, consulting and boards, is several times more now than he made as an elected official.

He gives speeches. He teaches a course at Penn each fall on political campaigns. He’s thinking of writing another book (A Nation of Wusses came out in 2012) because there are stories to tell. He gives constant advice to myriad political candidates, and raises money for “every Tom, Dick and Harry,” and appears on TV — on MSNBC semi-regularly to talk politics and NBC Sports Philadelphia after every Eagles game. He goes to 15 or so baseball games every summer and watches dozens more. And he’s raising money for Joe Biden and doing whatever he can to promote his candidacy. For normal people, this would be a lot. For Ed, the pace has slowed a bit, though not so much because of his current physical problems — he’s soldiering on with that well-known brio. “But I know fewer people each year,” he says, “and fewer people know me.”

Ed has a talent for engaging with whatever is on his plate; his work in the late ’80s for Mesirov Gelman in Philly, repping asbestos companies, wasn’t exactly the moral high road of lawyering, which he readily concedes. But even with that, in the challenge of presenting cases, in creating office sports pools, Rendell found his way: “I always had the capacity to make fun.” He says he could live on 60 grand a year and eat pork and beans, because he likes pork and beans, and he isn’t bothered by his physical problems as long as he can get around to do what he needs to do. It feels like an afterlife well lived.

All of which makes it hard to think of Ed alone, at the end of his day. Is he, I wonder, still … close to Midge?

“Oh yeah,” Ed says. “She sends me texts almost every day.”

He’ll be leaving 50 percent of his estate to Jesse and his family and 50 percent to Midge. “With the understanding” — Ed Rendell smiles, since the point is so obvious it’s funny — “that I’m going first.”

Our third afternoon together, Ed has just been driven back from his office in the Bellevue by Jerry, a part-time aide, who sticks around for a minute and sweeps up around Royal’s bed, which doesn’t bother Royal, who is still in the bed; she has the utmost patience, having seen Love, Actually, her master’s favorite movie, countless times. Ed parks at his desk in his small study once again, dressed in a polo shirt and khakis, his belt having missed two loops in back. It’s time to talk turkey:

Joe Biden. Ed’s guy.

Whatever one thinks of Biden, it’s not that he represents anything resembling a fresh start in how national politics might be conducted in America.

Ed didn’t just reemerge in national politics as the current race heated up, of course. Four years ago, he was a big Hillary Clinton supporter. Now, being anti-Trump is easy; taking on progressives is a little trickier, given the way political winds are blowing. But Ed easily warms again to how foolish he thinks leftists can be. Take, for instance, reparations for African Americans as recompense for 300 years of racism:

“I consider myself a progressive,” he says, “though now I’m thought of as a moderate, slightly left of center. But you can be progressive and be realistic.” Then Ed goes broad: “For example, do I think African Americans got screwed horribly by people of this country and our rulers — of course they did. Did Native Americans get screwed? Almost worse than African Americans. Did Irish Americans get screwed badly by people in this country? So, the idea of reparations: Can you imagine what would happen if the federal government passed a bill that each African American family gets a check for $100,000? Native Americans, Japanese Americans — the Japanese were interred during World War II.” They’d go crazy, Ed Rendell says, at the unfairness of singling out African Americans to square the ledger. “Why the fuck don’t progressives understand this?”

Biden, Ed says, gives the best answer on how to redress wrongs of the past: Give people opportunity. Jobs.

What’s more, Ed says, the media have the ’18 election all wrong in calling it a great progressive victory. All over the country, in races for governor and House seats, it was moderates who won, not progressives. Including the Fab Four, the quartet of female Congresswomen elected in Pennsylvania. Moderates!

Photos in Ed Rendell’s office. Photograph by Adam Jones

Later, I’ll give highly progressive Kendra Brooks a call. Brooks won an at-large seat on City Council in the fall by boycotting the Democratic Party altogether; she raised money through the Working Families Party. I ask Brooks, the mother of four, who grew up in and lives in Nicetown, what Ed Rendell means to her. What did he do for this city?

There is, for a long moment, silence. Then Brooks, who champions more affordable housing and rent control, says that he did some great things, but her silence was really the answer. Ed was mayor a long time ago, when she was young. Did it feel like he was part of an old-school method of solving the problems of an impoverished city by building bigger? “Yes.” Her goals are different. As Brooks puts it, “I just ran on basic humanity.”

“What progressives don’t understand is that we need rich people, too,” Ed Rendell says in his study, sounding for a moment like a trickle-down Reaganite.

Okay, so why Biden?

“Because I believe the best mayors, governors, presidents are good people. And Joe Biden is a 100 percent solid gold good person. He’s smart — maybe not Bill Clinton-smart, but sure smart enough to be president and to attract tremendous people around him. I think he’d be a fine president.”

Frankly, that sounds like average Joe. What of the criticism that we need a much more transformative president?

Ed, struggling to sit up a little higher at his desk to find relief for his back, thinks for a moment. “The same thing might have been said about the governor of New York in 1932. ‘Oh my, why elect him, he’s not progressive at all, he’s not going to make the seismic changes we need.’ Who made the seismic changes? FDR.”

If Joe Biden wins, Ed says, “I’d like to be chairman of an infrastructure bank. If I’m physically able. I’d only have to be in D.C. four days a month.”

Infrastructure — it might not sound too sexy. But then again, back when Arnold Schwarzenegger, along with Ed and Michael Bloomberg, founded Building America’s Future, the then-California governor defined to his son just what it is: “The stuff that Daddy blew up.”

Ed Rendell wants in, now, on rebuilding America.

Published as “Ed Rendell Still Has a Few Things to Say” in the March 2020 issue of Philadelphia magazine.