This Quaker Sex Ed Teacher Says Your Kids Need to Be Porn-Literate

As pornography is ever more accessible — yes, your kids are watching it — Al Vernacchio’s revolutionary approach to sex education is exactly what the sexologist ordered.

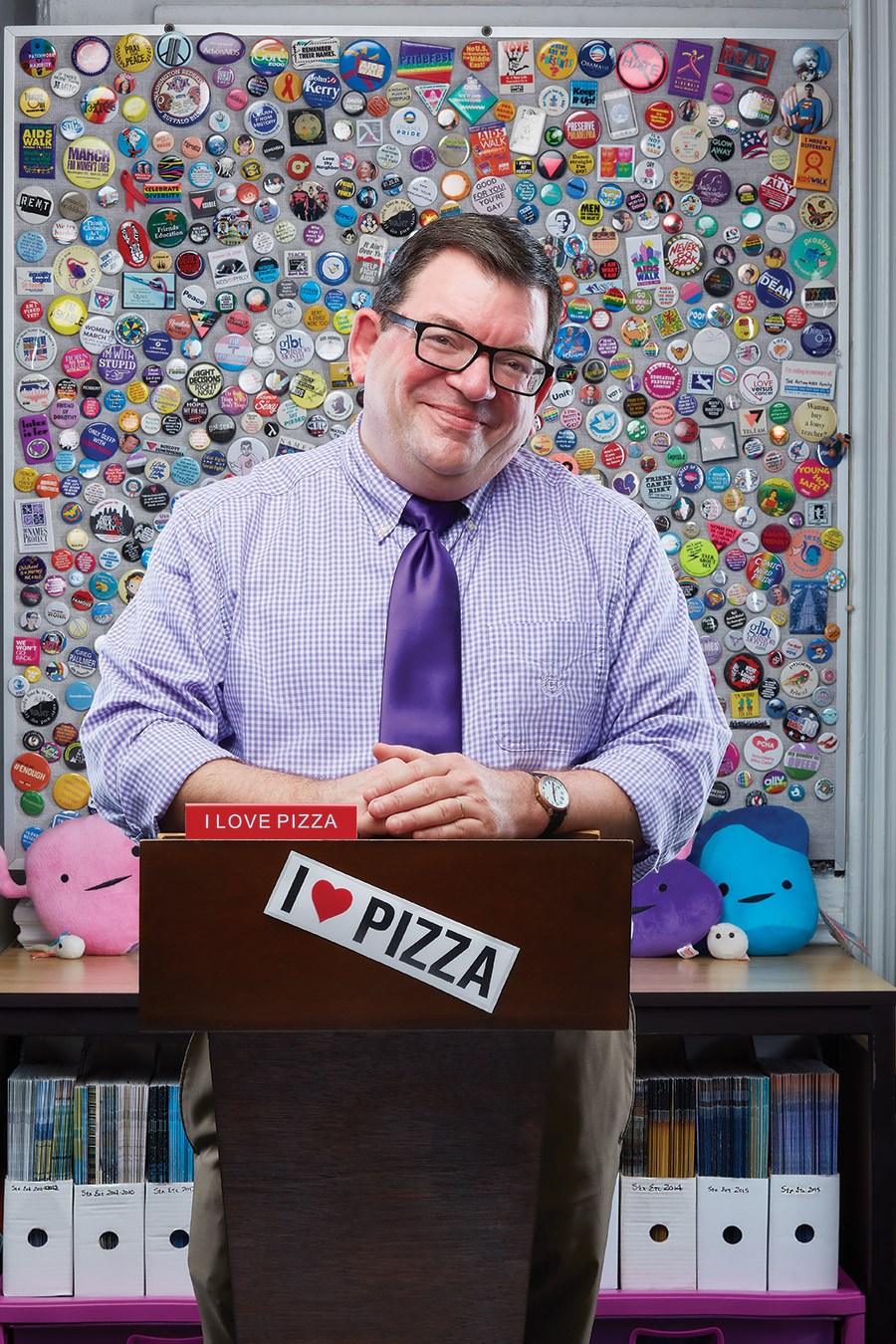

Photograph by Stuart Goldenberg

An upbeat Al Vernacchio sits across from me in a hip, plant-filled coffee shop in Haverford. He’s describing the hoops that people had to jump through to get their hands on porn back in the ’80s.

“When I tell kids what it involved to get porn when I was a high-school student, they’re in hysterics,” laughs Vernacchio, a short and stout 53-year-old with dark hair, rosy cheeks, and sort of geeky rectangular glasses. “You had to actually have a face-to-face conversation with somebody. You had to buy a magazine or rent a movie from a video store.”

Vernacchio talks to kids about porn because, more and more, it’s his job. He teaches sex education at Friends’ Central, the elite pre-K-to-12 Quaker school in Wynnewood. Roughly 15 years ago, “as soon as it became clear that the landscape had shifted so dramatically,” he says, he started incorporating “porn literacy” into his lessons. The emerging subject is exactly what it sounds like: It’s grounded in the understanding that kids (whether we like it or not) are watching porn, and that we need to provide them with the critical thinking necessary to understand its messages.

After all, the dirty magazine and VHS-tape days are a far cry from the deluge of X-rated content available with a few clicks of the mouse today. Modern kids don’t need to look far to find porn; all they need is the internet. Ever-easier access brings concerns: Parents, researchers, legislators and educators are worried about what kids are learning from their screens. While there’s little definitive cause-and-effect research on adolescents and porn (studying it is ethically challenging), studies have shown that kids are often first exposed to porn — some of it depicting violent or criminal behavior — in their early teens. And analysis has correlated pornography usage with sexual aggression, increased casual sex, and stronger gender-stereotypical sexual beliefs. When I ask Vernacchio what he thinks kids are taking away from porn, he doesn’t miss a beat.

“They learn that men are supposed to be sexually aggressive,” says Vernacchio, who’s known for his TED Talks on sex education and has become a go-to source for the New York Times. “They learn that women are objects. They learn that in the absence of consent, you don’t need a clear ‘yes.’ They learn that sex doesn’t require communication. They learn that you’re supposed to know what to do — like this knowledge gets preloaded into you, and if you don’t know, there’s something wrong with you.”

No wonder Vernacchio is gaining national attention. Pornhub, XVideos and Live-Jasmin are among the 50 most popular websites in the United States today, according to web analysis firm Alexa Internet. Here in Pennsylvania, in January, at the peak of the #MeToo movement, state House legislators unanimously passed a resolution recognizing pornography as a “public health crisis for young Pennsylvanians” and called for “education, prevention, research and policy change at the community and societal level.”

That’s where someone like Vernacchio could help. He’ll tell you that despite our culture’s obsession with sex, we’re completely lost when it comes to talking about it — especially with our kids. But the answer, he says, isn’t banning pornography.

“Is porn harming our culture? Yeah, I think it is,” Vernacchio says. “And we do have to find ways to stop that harm. But that’s not the prohibition of porn.”

What is the solution? “Better sexuality education,” he says, his voice lightening a little. “That’s more commonplace conversations about porn and what it is.”

It’s a warm day in April — the first of the year that feels like spring — and a chatty “Mr. V” welcomes his ninth-grade students as they file into his sunlit classroom. There’s a lot here to catch the eye. The walls are covered in pizza paraphernalia: plush toys, stickers, key chains. Atop the bookshelves are pillows shaped like testicles and uteruses. Then there’s the display of hundreds of colorful pin-back buttons with mottos like “Use condom sense!,” “Frisky can be risky” and “SEX — Talk with your kids about it!”

The school day is almost over, and the students at Friends’ Central sit in groups in their hoodies and jeans as an animated Vernacchio, wearing a long-sleeve lavender button-down and an eggplant-colored tie, approaches the topic of the day: What is sex?

He strolls around the room passing out white envelopes. Inside each are pieces of paper describing various sexual acts, from kissing and feeling someone’s body parts to more advanced ventures, like fellatio and cunnilingus (which the ninth-graders have trouble pronouncing) and “penile penetration” of both the vagina and anus.

“Imagine your friend just told you, ‘Dude, I had sex last night,’” Vernacchio says. “What activities would have had to happen?”

The kids discuss the cards for a few minutes, then slowly shuffle to the whiteboard, where they use magnets to display their definitions of sex. Every group has different answers, but they all agree on one requirement: penile penetration of the vagina. Vernacchio has a problem with this.

He offers a statistic from renowned sex researcher Shere Hite: Upwards of 70 percent of women don’t achieve regular orgasm through penile sexual intercourse. (Newer research puts that number even higher.) Then come the questions for the students: Why is defining sex by a series of specific activities problematic? If sex is defined as penile-vaginal intercourse, do gay men and lesbians have sex? Are you still a virgin if you “have sex” that you didn’t consent to?

Throughout the class, Vernacchio challenges the students to think about sex not as certain activities, but rather as the conditions under which those activities occur — and, perhaps most importantly, whether or not both parties involved enjoy them.

Vernacchio’s goal as an educator is to help students figure out what, exactly, sex means to them and provide them with the skills they’ll need to navigate healthy relationships and, if they choose, sex lives. Few classrooms approach the subject as thoroughly and openly as his does. Which is why, perhaps, his TED Talk, in which he advocates for using pizza (What toppings should we get?) as a healthy metaphor for sex — as opposed to baseball, which he says is problematic — has become so popular.

In 20 years at Friends’ Central, Vernacchio has become well known and highly regarded at the progressive, creative-minded private school. Laurie Novo, who’s worked at Friends’ Central (including as co-principal) for 25 years, says she’s never heard a single parent complain about Vernacchio’s classes. In fact, they’re so wildly popular — especially the 11th- and 12th-grade “Sexuality and Society” curriculum — that the school once had to hold a lottery for seats. Casey Cipriani, a 2001 graduate who took the course’s first iteration, says she recalls other students — and even her own mother — asking to read her homework.

Vernacchio teaches comprehensive sex ed, meaning he discusses the full scope of issues surrounding sex: STDs and pregnancy, of course, but also porn literacy, consent, pleasure, LGBTQ and gender issues, sexting, and other information that tends to slip through the cracks in most classrooms.

For such a wide-ranging curriculum to work, Vernacchio says, it must start young: A successful, holistic sex education reaches from elementary school to graduation. He talks to fourth-graders about puberty, to fifth-graders about romantic crushes, and with preschoolers about issues like fairness and gender. He starts integrating porn literacy in ninth grade during talks about body image, gender roles and physiology.

Vernacchio begins every high-school class by answering anonymous questions submitted by students. When I visit his class in April, one of the queries is: What happens if you use a Hot Pocket as a sex toy? (Vernacchio deadpans: “It’s a waste of a perfectly good Hot Pocket.”) But for the most part, the questions are more sincere: I haven’t had my first kiss yet — is this a problem? (There’s no “right” age.) Is it normal to have a crush on more than one person at a time? (Perfectly normal.) What’s the average duration of sex? (Depends on your definition of sex.)

Vernacchio’s judgment-free (and slightly dorky) demeanor encourages even the shyest students to approach him. More than once, a student has told him a story of sexual assault — which he says is one of the hardest parts of his job, “an enormous responsibility” that he doesn’t take lightly.

“There’s nuance to this work,” Vernacchio says. “The answers aren’t simple.”

Unlike kids today, Vernacchio didn’t learn about sex from the internet. He grew up in the ’60s and ’70s in a Roman Catholic Italian-American family in South Philadelphia. His parents raised him and his younger brother in a tiny rowhome near 10th and Bigler streets, in the Stella Maris parish. Pretty early in life, Vernacchio realized two things: He was gay, and no one (not his parents, not his teachers at St. Joseph’s Prep) was very interested in talking to him about it. He recalls only two “sex talks” with his parents: a hurried spiel when he was 13 from his mom, who called intercourse “the marriage act,” and, two years later, a lecture from his flustered father, who confused the words “masturbation” and “mastication.”

So Vernacchio, a curious kid who liked comic books and cartoons, spent hours in the library memorizing entries in the sexuality section. When he felt comfortable enough, he came out to his parents. He was 19, and the three of them were in the living room. They told him they loved him — and then asked him to talk to a priest. He agreed, under one condition: They also had to see a priest, but one that he would choose.

“We had dueling priests for a few weeks,” he recalls. “And then it just settled into silence.” His parents’ inability to discuss something so consequential is part of the reason Vernacchio is so open about sexuality today. “They missed out on a huge part of my life,” Vernacchio says of his parents, who are both deceased. “My parents did the best they could, and I don’t fault them.”

Vernacchio graduated from Saint Joseph’s University in 1986, the only theology major in his class, and later earned a master’s degree in human sexuality education at the University of Pennsylvania while teaching English and religious studies (which included sex ed) at St. Joe’s Prep.

After he was laid off with a handful of other St. Joe’s Prep teachers in 1993, he spent four years doing HIV/AIDS advocacy work. In 1998, missing teaching, he applied to Friends’ Central. Since then, he’s converted from Catholicism to Quakerism. He made the switch five years ago, he says, upon discovering that Quakerism and sex education are “speaking the same language: how to be your most authentic self, how to create authentic relationships, and how to leave the world better than you found it.”

Friends’ Central’s Novo tells me that Quakers have always been at the forefront of sex education: “They believe people have an enormous responsibility to treat everything with respect, and that includes the body. The atmosphere gives you a leg up on making [classes like Vernacchio’s] successful.” Yet she doesn’t think comprehensive sex education should be an “especially progressive” idea. Novo believes that as porn becomes increasingly “pervasive and powerful,” arming kids with ways of thinking about it “is a responsibility of educators.”

Vernacchio opens his class in April with a quote often attributed to Oscar Wilde: “Everything in the world is about sex except sex. Sex is about power.”

The resolution that the state House passed in January posits that “children and youths are exposed to pornography that often serves as sex education” and calls for education to address the “epidemic.” In doing so, however, it highlights hypocrisy: Pennsylvania doesn’t mandate sex education in its public schools. (Only 22 states and Washington, D.C., do.) State law requires that public schools provide HIV education but not holistic sex education, which has actually been shown to reduce levels of teen pregnancy. In the past, state legislators have thwarted efforts to change that. In fact, a bill introduced in June 2017 by Representative Brian Sims that would require more extensive sex ed has yet to receive a hearing.

For these reasons and more, Vernacchio says the resolution isn’t going far enough to address the issue of pornography.

“I get why people move to legislation,” he says, “Because once you start unpacking everything that makes porn the way it is, you have to talk about power and patriarchy, and people don’t like talking about that.”

The issue of teaching students about sex often leads to fierce cultural and religious backlash, stalemating any type of overarching sex-ed policy in the United States. Big shifts in sex education have tended to occur on the heels of an advancement or a crisis — the introduction of the birth control pill in 1960, the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s.

In his 2015 book Too Hot to Handle: A Global History of Sex Education, Penn professor Jonathan Zimmerman writes that public schools are being forced to play catch-up in the internet era. Now, he wonders if the debate over pornography will lead to another sex-ed revolution — as the topic is of concern on both sides of the aisle.

“If we can get people of every political side to agree that there’s too much ugly and prematurely sexualizing imagery,” Zimmerman says, “and that our schools should have a role in trying to counter and control it, that would be the most promising bargain.”

Ultimately, Vernacchio’s approach to sex education is simple: If we can talk about sex, we can make smart choices about sex. Yet it feels revolutionary in a society that has largely failed to initiate the conversation.

As I observe Vernacchio’s class, I think of a 1912 quote from activist and suffragette Jane Addams: “The child growing up in the midst of civilization receives from its parents and teachers something of the accumulated experience of the world on all other subjects save upon that of sex. On this one subject alone each generation learns little from its predecessors.”

I can’t help but wonder: How will Vernacchio’s students talk to their kids about sex?

At the end of the class, the students pack up to go. They face Mr. V, who leaves them with this: “If you’ve watched more than three porn videos, you’ll notice that stuff always happens in the same order,” he says, referring to the note cards he distributed earlier. “A lot of you are at a point of making decisions about sex. Remember that you have some say in the definition.

“When you do decide to have sex,” he says to his class, “I hope it feels amazing.”

Published as “Is Your Kid Porn-Literate?” in the June 2018 issue of Philadelphia magazine.