Vince Fumo Would Like to Be Vince Fumo Again

How does that make you feel, Philadelphia?

Photograph by Justin James Muir

The host wore his tux, and the bar was open, but anyone with eyes could see the empire eroding.

State Senator Vince Fumo stood there, smiling, greeting guests, doing his best to maintain the institution. Fumo’s Harry S. Truman fund-raising dinners had, for 20 years, comprised a sneaky in-joke, celebrating the May birthdate he and the former president share and expressing Fumo’s raw political power. In the past, he’d drawn up to 400 guests who paid $5,000 for a cocktail party, a meal, dancing, and proximity to that power. But this final event, in May 2008, drew about half that number. Fumo was game. But Ann Catania, his longtime decorator and party planner, says, “No one knew what to say to Vince.”

Death, of one kind or another, seemed near at hand. Fumo was scheduled to go on federal trial, facing a staggeringly long 141-count indictment that included charges of fraud and obstruction of justice. He put a brave face on the upcoming trial, but a couple of months before the Truman fund-raiser, his heart conveyed his fears — delivering an attack so severe that he spent a week hospitalized. He also announced his retirement from the Senate, forgoing a run for reelection. The signature tux he sported at so many dinners suddenly looked less resplendent and more funeral black.

Fumo’s salad days had lasted almost three decades. His official bio boasted that the Daily News dubbed him “Super Senator” — the able, sometimes vicious Democratic Party boss and bringer of great stacks of cash from Harrisburg. When Adrienne Thomas, an attorney and longtime Fumo aide, walked into the Loews that night and saw the smaller crowd, a piece of her broke. “I was just so upset for Vince because he had done a lot of good for people,” she says, “and for so many to desert him before he even had his day in court … I was furious.”

Fumo’s days in court later that year would only yield more misery: conviction on 137 counts and, later, a trip to federal prison in Ashland, Kentucky, in shackles. City journalists affixed a new tag to the longtime super senator: “disgraced.” Fumo’s image, a tale of So. Much. Winning, transformed into one of almost total loss: his political career, his reputation, even his children — Nicole, Vincent and Allie — who no longer speak to him.

Fumo did four years in jail, emerging in August 2013 and staying mostly out of sight. But that time in hiding is coming to an end. Vince Fumo, now 74, has been making moves. He’s opened a consulting business, advising private clients on business and governmental strategies. He’s struck up a surprising new relationship with former Inquirer editor Bill Marimow. And, most ambitiously, he’s publishing a book about his life and times.

“Let me tell you something,” he says one day from the sitting room couch of his mansion on Green Street in Fairmount. “Yeah, politics are all fucked up. But that’s human nature — and I mean the good of it, the nobility, and the bullshit, too, the greed and the ambition. All of it is human nature!”

Vince Fumo. Photograph by Justin James Muir

At first, these words seem purely self-serving — the desperate attempt of a convicted felon to pin his moral failings on humanity. But the words seem to free Vince Fumo — to thrill him. He scoots forward on his couch and waves his hands, as if imploring me to see what he’s conjuring — an epic tale, something tragic and Greek, or Catholic: a vision of man’s fallen nature, something dualistic and far more complicated than the one note (disgraced!) to which his life has been reduced.

What Fumo wants is redemption. But in typical Fumo style, he wants it on his terms. He wants to be recognized in all his complexity as a man who fell, and a super senator, too. But mostly, he wants to be welcomed back into this city’s life.

Vince Fumo walked into the Prime Rib last year, to the bar, and felt a sudden tug at his arm. “Vince,” a woman said. “How you doing?”

Startled, Fumo looked, but the woman was hugging him, so close he couldn’t see her face. “Did I have sex with this girl?” he thought. Then she pulled away, and he saw: Deborah Merlino. Later, in strolled Joey Merlino, her mobster husband — still heavily muscled in his 50s.

Fumo had met Deborah years earlier through a mutual friend. He respected the way she’d raised her kids while Joey was “away,” and that night at the Prime Rib, he listened. Joey made small talk about the courts, but inside, Fumo panicked. His probation was scheduled to last another month. Meeting with this convicted felon, a violation, could land him in jail.

Fuck, he thought, realizing Merlino’s every move was probably tracked by multiple federal agents. “I gotta go,” he said.

Merlino looked surprised, till Fumo’s predicament hit him. “Oh,” he said. “Yeah.”

Recalling this story, Fumo erupts in laughter. But the larger point isn’t lost: In the eyes of the law, he and Joey Merlino are of a piece, two convicted felons walking into a bar. The comparison between Fumo and the gangster bears some truth — both men knew how to gather, use and abuse power, for instance — yet also looms as grossly ridiculous.

Merlino took an already murderous and vicious organization — the South Philly mob — and made it worse. Fumo has become a living symbol of political corruption. His trial limped on for five months, revealing multiple embarrassing and repugnant details: He used his Senate staff to pay his bills, manage his checkbook, oversee renovations on his Fairmount mansion and help with campaign work. He raided a nonprofit he controlled for shopping sprees at Sam’s Club and to purchase Oreck vacuum cleaners, 19 in all, for each floor of his multiple homes. He retained a private eye — also paid for with taxpayer dollars — to, among other tasks, follow a girlfriend he wanted to get busted for drunk driving. His staff was ordered to delete emails, to try to thwart federal investigators he knew were on his case.

But Fumo also did something more, serving for many years as one of this city’s saviors. He constructed a political empire, controlling WAM, or “walking around money,” in the state Senate to fund projects in individual districts. Using his position as chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee, he brought billions to Philadelphia, propping up the city’s sagging tax base with the state’s purse. “The success of the Rendell administration,” says Ed Rendell, “doesn’t happen without Vince Fumo.”

Rendell’s former chief of staff, current Comcast executive David L. Cohen, notes that Philadelphia has undergone a kind of renaissance in the past 30 years, managing — despite ongoing struggles with poverty and crime — to galvanize a vibrant collection of diverse, thriving neighborhoods and a seemingly unending succession of new residential and business construction. “Without Vince guarding the state budget in Harrisburg and bringing home all the money he did — billions just in our time in office — all the good things that have happened here just wouldn’t have been possible,” says Cohen.

Fumo’s many successes, in fact, are far too numerous to recount here. He wrote and helped pass legislation mandating instant background checks on gun purchases. He saved the city from a financial crater when he helped establish the Pennsylvania Intergovernmental Cooperation Authority. He co-founded the city’s Columbus Charter School, one of the most successful in Philadelphia. He led a charge, in the late ’90s, for increased competition among telecom providers, yielding better services and rates. He sued PECO, in 1996, over planned fee hikes, forcing a rate reduction and a 10-year freeze on increases. Unfortunately for him, that’s where the trouble began. Because he also started a nonprofit, Citizens Alliance For Better Neighborhoods, and wheedled millions out of PECO on its behalf — a maneuver one old staff member describes as “legal extortion,” a kind of Merlino-lite act that garnered $17 million in “donations.”

The shakedown caught the attention of the Inquirer and federal investigators, who found nothing to prosecute in the deal but started tracking the super senator’s moves anyway. Much of what they saw qualifies as great government: Fumo directed Citizens Alliance to use a big chunk of that PECO money to acquire properties in Fairmount and Passyunk that it rented out to sharp new businesses, transforming Passyunk, in particular, into hipster hotness.

He oversaw the legislative bill that brought legalized slots gaming to Pennsylvania, triggering great enmity among the masses and a massive influx of new revenue for the city (more than $10 million per year for it and its schools) and state (about $3.2 billion per annum).

There’s more, but even if Fumo had stopped there, he would loom as perhaps the most important Philadelphia politician of the past 50 years. “There’s no question,” says Franklin & Marshall College political scientist Terry Madonna, “he was one of the most effective politicians we’ve ever seen in terms of just getting things done.”

As the darker, pettier side of Fumo emerged — the side that absconded with thousands in ill-gotten appliances and power tools — the city media, particularly the Inquirer, responded by going pretty much Full Fumo, covering him in an average of four stories per week over a five-year period. Much was lost in the flood, including all sense of proportion and nuance. In fact, after Fumo was originally sentenced to 55 months in prison, the media comprised a kind of cheering section when federal prosecutors formally sought a new sentence of at least 15 years — a jail term greater than that served by Merlino, the gangster, who got just 14. What was lacking was the sense of sadness that should have attended Fumo’s political passing. The feds didn’t just get a corrupt pol; Philadelphia also lost one of its most capable and important champions — to his own corruption, yes, but we lost. What was also missed was the wha? of it all — the conundrum of how a wealthy super senator came to be a thief, buying turkey fryer accessories worth $124.91 with someone else’s money. Vince Fumo’s fall was a massive story, fueling an endless stream of coverage, but somehow, it got away.

Up close, Vince Fumo hasn’t changed much from the figure we saw marched off to jail. His face is still jowly, and he still juts his jaw out, teeth bared, in mid-sentence, giving him a wolfish appearance. He also still smiles frequently and laughs a raucous laugh.

Fumo’s relative anonymity since he emerged from jail is a product of both design and circumstance. His clients — whom he declines to reveal — aren’t exactly itching for a guy bearing the scarlet letter to come strolling into their corporate offices. So he works mostly from an office in his Green Street manse, having dinner with his girlfriend or friends in restaurants around town and doing a lot of cooking.

Though he lacks any discernible power, visits to his mansion still feel important. Guests must be buzzed in through a 10-foot-high iron gate, then shuffle past a pair of decorative eagles who guard the walk and up a flight of steep stone stairs. Fumo himself comes to the door, in old-man-around-the-house chic — crisp jeans, tightly pressed button-down shirt and slip-on shoes. Each time I visit, he marches me straight to the sitting room, plops himself down on the claw-footed couch, and waits for a question. But his agenda is clear: He’d like to be known more in accordance with how he’s always seen himself; he recognizes it’s gonna be a tough sell, but, well, he still has trouble believing it. “After everything I’ve done for this city,” he says at one point, then stares a little wild-eyed at the rug underfoot — as if some explanation might be there in the expensive weave.

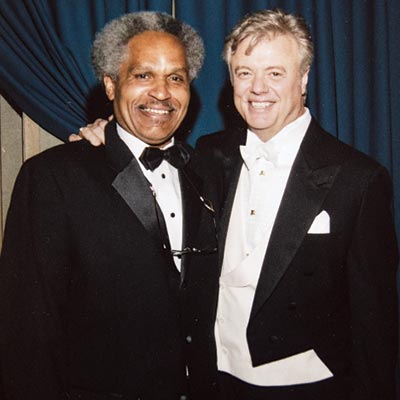

Fumo alongside former mayor John Street.

He’s had conversations about various ways to reintroduce himself. He considered running for a Democratic State Committee post, the rare political position he could hold as a felon, but changed his mind. Former mayor John Street spoke to him about possibly appearing together at some high-priced fund-raiser, to give a talk on politics. He’d like to revisit old colleagues in Harrisburg, meet new ones and offer some advice. But he got a taste of media attention in September 2014, when the Inquirer reported he’d been hired by Murphy Marine Services in its bid to develop 200 acres in the Navy Yard. The tenor of the story suggested his lingering toxicity. So he’s wary.

The book he’s self-publishing, though, will put him back in the public eye whether he’s ready or not.

Titled Target: The Senator, it’s 431 pugnacious pages that re-litigate his marathon prosecution, hack at the Inquirer, and stack his various victories in a glittering pile. The result isn’t exactly hagiography. Fumo emerges as a complicated, vindictive and troubled man — a serial philanderer who blundered through a couple of marriages, leaving pain in his wake, and only sporadically engaged with his children. The book concedes that he committed actual crimes but contextualizes them as unworthy of a long jail sentence. In public relations terms, the tome will probably be a spectacular act of self-immolation. No convict gets to step out, lecture us on how we should love him, and expect anything else.

Further complicating matters, the book also bears a tricky provenance. Credited solely to author Ralph Cipriano, Target was in fact paid for, in part, by Fumo, who reviewed it prior to publication. Cipriano, who says Fumo never demanded a single change to make himself look better, has his own tortured history with the Inquirer. As a reporter there, he successfully sued his own paper for libel when an editor publicly and falsely accused him of not backing up his facts. And so this pairing will create the unmistakable whinge of axes grinding.

Of course, none of these concerns — serious as they are — render Target any less true. And given that no one else in town was stepping back to take a new look at Fumo’s life and career, it’s perhaps understandable that he decided to pay someone to do so. As Target argues, some of the allegations against Fumo wither under scrutiny. Fumo argued that his staff did favors for him on their own time, and his crew did have a well-deserved reputation for working all day and deep into the night, living by the slogan “We get shit done” and rendering claims that he was cheating the state suspect. “I always thought of those charges, of the staff doing personal favors for him, as a kind of narrative-building exercise by the prosecutors,” says longtime Daily News columnist John Baer. “But I think if you follow how hard that staff actually worked, it becomes much more difficult to say that the state didn’t get its money’s worth.”

The prosecutors can also be credibly accused of inflating the number of charges. In court, prior to delivering Fumo’s final sentence, Judge Ronald Buckwalter critiqued the prosecutors for growing five main crimes into 141 counts spread over a 267-page indictment.

In person, Fumo seems at once pleased with the book and ambivalent. He doesn’t intend to promote it aggressively. He wants it to exist, a thing between hard covers with his side of the story written inside. This admission really does make the mythic man look wounded: his first post-jail media interviews, a book … He is at once sticking his head out and feigning — perhaps even nurturing in his own heart — an indifference to the results.

Viewed closely, then, Fumo’s current “freedom” only describes his legal status. In psychological terms, he’s imprisoned by his past, disgraced. And in this context, Target reads like a letter from an inmate — a long, tangled plea to be seen as more than the sum of his charges. To be seen as a good person.

As a very young senator, Vince Fumo fixated on a particularly lofty prize. Just four years into the job, in 1982, he declared himself a candidate for Democratic chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee, a post granting him power only his Republican counterpart and the governor could rival.

“I campaigned for it — hard — with my fellow senators in the Democratic caucus, but I lost,” Fumo says. By all rights, the junior senator should have expected defeat. But he was furious. “I wondered,” he says, “who fucked me.”

Such internal Senate balloting was secret, to prevent precisely the animus Fumo was feeling from impeding the government’s work. Fumo didn’t let that stop him. He got some fellow senators’ signatures, then strolled into the office where the ballots had been counted to compare handwriting on the anonymously cast slips with what he’d gathered. By the time his colleagues realized what he was doing and locked away the voting slips, Fumo felt reasonably sure of their votes. Thus armed, he asked his secretary to write each member of the Democratic caucus a note. To those who’d supported him, Sue Skotnicki wrote something like: “Thank you for your vote … maybe we’ll win next time.”

To those who’d voted for anyone else, he asked Skotnicki to write: “I understand you couldn’t support me this time. Maybe I can win your support next time.”

Skotnicki sent the letters out; Fumo waited.

He would become known over the course of his political career as a man not to cross. Current state attorney general Josh Shapiro, in an anecdote recounted in Target, says that as a state legislator, he once pissed Fumo off; the senator responded by killing a legislative item both men wanted. “I just became a terrorist,” he told Shapiro, “and blew up my own train.”

This episode sounds repugnant, but politicians really do begin to see things differently than most of us. Shapiro confesses to Cipriano in Target that Fumo’s thuggish maneuver actually impressed him as a vivid demonstration of pure power.

Longtime Philly political operative Thomas Henry Massaro, housing director for ex-mayor Bill Green, says he once earned Fumo’s ire by firing a ward leader the senator favored. Fumo kicked open Massaro’s office door in City Hall and peppered him with “f-bombs,” then left, smiling. Massaro realized he’d been treated to political theater: Fumo could go tell “his guy” he’d exacted a form of revenge. But his smile told Massaro everything was okay.

Fumo understood, in other words, how to use both hard and soft power — the hammer and the velvet glove. And when, as a young senator, he was stymied in his bid for the appropriations committee, he used both. He exacted no revenge on those who didn’t vote for him. But the notes Skotnicki stuck in the mail sent a powerful message: “I know what you did.”

Two years after he lost in his first bid for state appropriations chair, he ran again and won. The good times started then, the Truman dinners, a period of 23 years in which Fumo only ever seemed to gain power, which he used to help the city and in more questionable ways, too.

One ex-employee says Fumo had a propensity to “treat people like pawns.” He sometimes threw open the door to his inner office, saying, “You should all hear this,” then hammered some hapless fellow state senator, who had no choice but to sit there and take it. The anger always existed inside Vince Fumo, along with whatever softer angels were in his nature.

As ex-cons go, Vince Fumo sure did land on his feet. He led a rich life prior to jail, working two jobs beyond the Senate that netted millions: chair of First Penn Bank, which was founded by his grandfather, and rainmaker at the law firm Dilworth Paxson. He plowed that cash into homes in Florida and at the Jersey Shore, a farm in central Pennsylvania, and, of course, that big Fairmount manse. And he moved through the world with curiosity and competence, acquiring degrees from Wharton, Villanova and Temple along with certified genius status from Mensa and licenses to practice law, charter a boat, and even work as an electrician. The trial bled him, for sure — costing him millions in fees and restitution — but he still wound up in one of the finest homes in the city.

When requested, he grants a tour of the house that takes more than an hour, like a trip to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater. The home is tremendous, a castle in the city, with generous outdoor spaces, heated sidewalks, a sweeping view of the Philadelphia skyline, and intricate Victorian-era detailing and woodwork throughout. When Fumo pads around the place, spouting his typical profanities — he’s famous for swearing, and in eight hours of recorded interviews for this story dropped 664 f-bombs (83 per hour) — the effect is surreal and even a little cheering, a rough-edged South Philly boy who grew up to live in an old-time European masterwork.

According to Fumo, he always scored exceedingly well on tests. But his ambitions were almost secret at first, fueled by an upbringing both privileged and despairing. His grandfather, founder of the bank, bequeathed his progeny distinct advantages but not mad riches. Fumo’s dad served as bank chairman, crossing the lines into the criminality of fraud and money laundering. The duplicity extended to his family life, too. Dad cheated on his wife, openly enough that his son knew the truth, and the wife — the boy’s Irish mother — had little recourse but to drink.

The young Fumo was coddled by his mom but took after his dad — hence the later philandering and convictions. The drinking, criminality and cheating left scars he’d deal with as an adult in therapy, and he never fit in with any peer group. His mixed Italian-Irish heritage netted him no clear allies in South Philly. During those early, angry years, he nurtured a desire to “show all those motherfuckers” they had underestimated the wrong guy.

As he grew, and wondered where he fit, politics looked like a chance to establish himself, to strike out in a territory his father hadn’t and grab the levers of power. And it’s easy — in fact, it’s Pop Psych 101 — to imagine his later expressions of raw power — berating another elected official, for instance — as a cycle repeating in a kid who had himself been bullied.

In these terms, the mansion, too, looms as a giant retort. And even when I tire of seeing one amazing room after another, Fumo doesn’t tire of showing them, opening still more doors to reveal still more rooms. Fuck you! the mansion screams. Just look what I did with my small bank.

Like all things Fumo, however, a full tour of his mansion includes glimpses of our fallen nature and a pervasive and inevitable sense of loss.

“This was Allie’s room,” he says, showing off a massive bedroom where his younger daughter once slept. And down the hall, “This was Allie’s craft room. I gave this room over to her. She’d … make things.”

Fumo’s voice, usually a high, energetic rasp, loses steam, like a teakettle removed from the stove. Looking around the craft room, hands in his pockets, Fumo confesses he doesn’t really do anything with it now.

Friends, political and otherwise, say losing contact with his kids is the disgraced senator’s greatest source of pain. He and his eldest, Nicole, the product of his first marriage, always had a strained relationship. He’s never met the three grandkids she bore, and he stopped sending birthday and Christmas gifts when he never received a response.

There is good reason for tension. Fumo and his first wife, Susan, with whom he had Nicole and Vincent II, separated in the early ’80s and arranged joint custody of the kids. She’s said in the past that Fumo barely interacted with Nicole and Vincent, even when they were in his care — using his Senate staff, in fact, to shepherd them through meals he was too disinterested to share.

For a time, Vincent continued to see him. So did Allie, his youngest, even after Fumo separated from her mother, his second wife, Jane. But they, too, cut off contact in recent years, after Allie and Vincent sued him over money he shifted from the trust fund he created for them to pay some of his legal fees. The family ultimately settled out of court. Their relationships never recovered.

Allie is married now, holds a Wharton business degree — which, Fumo notes, he paid for — and works as a talent development manager for Saxbys. She didn’t respond to multiple interview requests for this article, but during court proceedings over the trust fund, she stated that she could no longer “trust” her father. The last he heard from her was a text exchange this spring. He’d bought his current girlfriend a “teacup dog” and texted a picture of it to Allie, writing, “This is the new addition to our family.”

She wrote back, he says, telling him more or less, “You’re not my father.”

Vincent, a software engineer for Comcast, did agree to be interviewed, via email. “Over and over again he has proven to be uninterested in having a meaningful relationship with me and he has let me down countless times,” he writes. “I often tell people it’s like the Lucy and Charlie Brown thing with the football. Every time he cons me into thinking that I will get a chance to kick it and then at the last minute he pulls it away. It’s a pattern I’m done repeating.”

These days, the junior Fumo frequently dines at Bing Bing Dim Sum, an East Passyunk neighborhood institution. The place will be packed with diners, the streets thronged outside, and he’ll marvel at how few people, if any, realize his dad made this happen. “I’m very proud of what my dad accomplished,” he writes, but “I think that he truly is a person who has no care in the world about other humans other than how they can make him appear greater.”

For his part, Vince Fumo sounds depressed when he discusses his kids but never comes close to tears. “I think … when you’re in this kind of unique position, you keep reaching out but you don’t go crazy about it. Because you gotta be a realist and whatever’s in their minds is in their minds.”

He blames a combination of factors for the estrangement, mostly his long absences from their lives when he was consumed with work, and admits he’s written his children out of his will. “They’re very well taken care of,” he says, joking that at this rate, he expects to leave whatever he has to his girlfriend’s new dog.

There is a coldness there, and even the troubling suggestion that his love for his kids isn’t unconditional. But there is also evidence of that same inner conflict with which he regards venturing back out into the world. “I’ll keep trying,” he says, sending texts at birthdays and holidays. And he’ll hope, a little, for a response, but with no expectation he’ll get one.

His political relationships have a similarly ragged shape. He speaks with Congressman Bob Brady and counts David L. Cohen as a friend. He confers with his successor in the state Senate, Larry Farnese, from time to time. But Frank DiCicco, a former staffer and later City Councilman, doesn’t call so much now; others, like his former chief of staff and current mayor Jim Kenney, don’t call at all. Fumo says Kenney just … stopped. After Kenney won the mayoral election, Fumo’s assistant, Jermaine Veasy, had to talk his boss into texting a “Congratulations” message. Fumo did. But Kenney didn’t reply.

Fumo with his ex-chief of staff, current mayor Jim Kenney.

Kenney, through a spokesperson, declined to be interviewed for this article. Those who know him say he’s angry at his old boss for dragging all his staff members through the court process when he should’ve just taken a plea.

Target takes a stab at working out the puzzle of Fumo, the “How did he get here?” question moving to the foreground. There is even a moment when an epiphany seems imminent, late in the book, at Fumo’s final major court proceeding. Judge Buckwalter, in discussing an appropriate sentence, confesses himself thrown by the combination of good works and debasement at play in Fumo’s story. “Most agree,” he stated, “about Mr. Fumo’s total immersion in his job as state senator. Whether this was motivated by greed, ego, pride, envy, lust or other more noble motives, such as an honest desire to help the common people who found themselves in need, will never be fully resolved.”

On the matter of Vince Fumo’s character, that dud amounts to the book’s final word. In the biography Vince Fumo commissioned himself, a federal judge declares the riddle of Fumo’s heart to be one of the city’s great mysteries. The effect is like seeing Fumo peer into a mirror, throw his hands in the air, and give up — admitting he can’t quite figure himself out.

Not long after he arrived home from jail, Vince Fumo emailed then-Inquirer editor Bill Marimow. After a brief back-and-forth, the pair arranged to meet for coffee.

Marimow declined to be interviewed for this article, calling his relationship with Fumo “cordial” but preferring to keep it “private.”

Fumo says Marimow sends young reporters to him for history lessons in Philadelphia politics. He laughs at the unlikely nature of his relationship with Marimow, like the whole thing is some weird accident. But they didn’t just bump into each other at the store. Fumo emailed him, creating the whiff of a plan: Operation Marimow.

Fumo says he sent Marimow old transcript notes from his trial, critiquing the paper’s coverage, which might scan at first like an attempt to rehash old grievances. But cultivating a relationship with an icon at the Inquirer — Marimow is retired from his editor’s post yet still there — is also forward-looking, a sign that in Fumo’s mind, the game isn’t over.

“We’ve met out several times,” says Fumo, “and I invited him to lunch here at the house. I cooked him a steak.”

There is a growing sense, in Fumo’s circle and among those steeped in politics, that it wasn’t just the city that lost something when the super senator fell (disgraced!). The state lost, too.

Fumo, the consummate deal maker, kept the state budget process running — avoiding the months-long blockages that have impeded state government of late. But one ex-staffer opened our interview, before a single question was asked, by going on a long diatribe against the idea that Vince Fumo could be of any further use at all: “I am sick of hearing that Vince could fix things in Harrisburg! He couldn’t! It’s just not true.”

As political analyst Terry Madonna puts it, vibing with the ex-employee, a lot has changed since Fumo retired from the state Senate. For starters, the 2010 election included a wave of Tea Party Republicans, ideologues less interested in cutting deals than in watching government burn. Fumo actually agrees with this assessment but offers a solution. “I called Farnese,” he said during one of our interviews before the budget was resolved this fall, “and I told him Governor Wolf has one piece of leverage. One! And he needs to use it.”

That leverage, according to Fumo, was the power to stop paying on state contracts. Once the state rep from Indiana County started getting angry calls from state vendors, he’d come to the table and deal.

Hearing this, Madonna says, “Well, yeah. That’s Vince. He put his finger right on it.” But Fumo’s ex-staffer — the same one who said he treats people like pawns — exploded when he was told. It wouldn’t happen, he said, “because regular people might get hurt. And Tom Wolf is a pussy.”

Should Wolf have done it? Would the strategy have worked? And couldn’t Fumo, with his capacity for villainy, be useful, if only as the devil in someone’s ear, declaring the time for soft power at an end and whispering, “Go ahead. Get out the fucking hammer”? At this, Fumo’s ex-employee collapsed and slumped forward over the table. “Yeah. It might work. And I miss it. We need it.”

Fumo’s trial included a lot of information, probably too much, about the many years he spent in therapy. Cipriano’s book summarizes a report by a clinical social worker that was provided to the court and offers a slow drip of psychoanalysis. Fumo, an undersize only child, was picked on by other kids and grew up watching his parents keep secrets from each other. “He became comfortable dealing with contradictions in the character of his role models. He learned to accept the dualities … a useful skill set for a future politician.”

Fumo also suffered from anxiety, depression, insomnia and OCD, which can sometimes manifest in binge- or compulsive buying. At least some of that probably still pertains: On my half dozen trips to the mansion, not a day went by when Fumo’s stoop didn’t include between one and four boxes from Amazon. Fumo acquires so much stuff, in fact, that he discovered he’d lost more than he could track. He and Jermaine Veasy, whom he employs part-time, maintain a written list of items he can’t find, so they can keep an eye out for them around the mansion.

There is medical research indicating that shopping really can be addictive — yielding spikes in happy chemicals like endorphins and dopamine. And author Rachel Shteir, after interviewing shoplifters for her book The Steal, concluded that there’s a deep psychological component to theft. The perpetrators tend to feel they’re owed somehow. Thieving provides compensation. Fumo, clearly, felt entitled. Is there anything in there, from the more frazzled threads of human nature, to help him understand why he ended up buying a $449 meat saw with money he’d raised to revitalize neighborhoods?

“I’m not sure,” he says. “I still buy things, I accumulate. … I had to take almost roll call of my boats.”

Fumo was stunned to realize he has 11 boats — none of them cheap. (His fleet includes a 60-foot yacht and a Hinckley, which Fumo calls “the Rolls-Royce of boats.”) But the telling part here is his own reaction: “I got 11 boats! I was like, ‘What the fuck am I doing here? Eleven!’”

Of course, many people have tried to psychoanalyze him. David L. Cohen envisions him as split between good and bad Vinces. His own son has concluded that his dad doesn’t recognize that other human beings have feelings.

“I will tell you,” says Ed Rendell, “these things, the lack of a relationship with his children, do hurt Vince, and there was a time when his oldest daughter, Nicole, had a job in my administration and I even tried talking to her about Vince myself.”

In time, I found myself sorting through Fumo’s behavior and the tangle of his past, trying to determine something as basic as his capacity to value others’ emotions or even to feel love. There is no question he has difficulty admitting the depth of his wrongdoing. But eventually, if pressed, he does. “I regret the Citizens Alliance stuff,” he says. “I think I just got … I got caught up in the whirlwind.”

There was so much money in his life, so much stuff, so much doing, that 19 vacuum cleaners, at $541 per, didn’t register.

“I lost touch,” he says. “I didn’t see any of it as important. A power saw?”

The portrait isn’t flattering to Fumo — a sense of entitlement so deep that he didn’t ever stop to recognize all the lines he was crossing — and he sags forward a bit when recalling his failures. He also confesses that a similar dynamic played out with his children.

“I know I wasn’t there for a lot of things,” he says. “And if I could do anything differently … maybe I wouldn’t be involved in politics.”

The arena was so demanding that he could spend every waking hour working or thinking about what to do next — from empire building to actual legislation. But he also believes that intensity would have colored any endeavor he undertook — that these kinds of failures, the lust to be swept away, lurked in his nature. Sometimes, he says, “You are who you are.”

Upstairs in his office, Fumo pulls out a pile of old photo albums, each stocked with nothing but pictures taken at his old Truman fund-raisers. The albums are unmarked, no dates, but there are lots of famous Philadelphia names in the pictures.

The most poignant shots include Fumo’s children, Vincent and Allie. They were still speaking to him then — he believes the shots are from about 2005 — and they appear to be having the time of their lives.

The ex-senator with daughter Allie and son Vincent.

We’re in the massive room Fumo keeps as a personal office, and he grins broadly looking at the photographs, lingering for a while over a series of shots that show him dancing with Allie. He can’t name the year, but he remembers the moment well enough to say, “We were dancing to our song: ‘Brown Eyed Girl.’”

Their happiness, in the shots, is unmistakable. But I find myself staring hard at these images to try and suss out Fumo’s real state of mind, even his heart. Fumo’s eyes shine with a delight that could reflect true love or merely narcissism. But other photos don’t seem to permit that kind of harsh analysis. In these final images, Allie’s eyes are closed while Fumo remains fixated on her, his expression so soft, so soulful, that he appears caught up in a whirlwind of a different sort — an appreciation for the woman his daughter was fast becoming. A father’s love — which is to say, all the love in the world.

Of course, it makes sense that Fumo’s family — given their troubled history — would wonder about these things, and want to be sure not only of his capability and his wisdom, but his love. A city, on the other hand, doesn’t necessarily require its politicians to love it. A city only needs its representatives to get shit done.

Pennsylvania, like America as a whole, has a long history of rehabilitating its politicians, of watching them reinvent themselves after jail terms for corruption. Former Republican House speaker John Perzel pleaded guilty to theft, using millions in taxpayer dollars to develop sophisticated computer programs to aid his own and other Republican political campaigns. He works as a lobbyist now. Bob Asher, once chairman of the Pennsylvania Republican Party, was convicted in a federal corruption trial in 1986 of conspiracy to commit bribery, perjury and mail fraud. His co-defendant, Budd Dwyer, killed himself on live TV just prior to sentencing. Asher did one year in jail, then served on multiple boards, including the Salvation Army, even ascending to the Republican National Committee.

Fumo’s predecessor representing South Philly in the state Senate, Buddy Cianfrani, went away for putting “phantom employees” on the Senate payroll, then emerged to become a popular Democratic ward leader.

Fumo repeatedly returns to this subject, and how Asher’s crimes now seem forgotten. “I called Marimow,” he says, “and left him a message: Hey, how do I get the Bob Asher treatment?”

Right now, there seems to be no consensus on how or even if Vince Fumo could rehabilitate himself. “I think … I hate to say it, but he might really be too toxic for a public role,” says his old staffer, Frank DiCicco.

“I don’t see how he can be any sort of front person for an organization,” says Rendell. “He can’t. Anything he does will have to be behind the scenes.”

At first, the notion of Fumo as a background player might seem like an impossibility — could his ego take it? But there is, in fact, one subtle sign that Fumo could handle it. His relationship, or lack thereof, with Mayor Kenney suggests a maturity — perhaps even a depth of real feeling — that Fumo’s own kids don’t associate with him. Fumo is, flatly, ticked off that Kenney doesn’t speak to him anymore, and says at one point: “If it wasn’t for me, Jimmy would be selling cars someplace.” But in this instance, Fumo’s actions probably speak a lot louder than his words.

During his race for mayor, Kenney showed Fumo no loyalty and even ran with the backing of Fumo’s longtime political arch-nemesis, Johnny Dougherty. If Fumo had wanted to drag Kenney down, it would have been incredibly easy — a rare chance to leverage his toxic legacy and exercise real power again.

Kenney’s entire candidacy, in fact, hinged on distancing himself from his old boss — on building a coalition that included city progressives, a group that finds Fumo repugnant. How many minutes would it have taken Fumo to call a couple of reporters and start talking about his hopes for the Kenney administration? He likely could have ended Kenney’s prospects, just that fast. But he didn’t.

Could this Fumo, the one who gave Kenney his political freedom without getting anything in return, find some project to undertake in the city, an outfit to help, and step out into the light?

One of Fumo’s newer friends, former CBS TV exec Michael Colleran, thinks it’s possible. “In my career in TV,” he says, “I came to realize that viewers really love to see corrupt politicians taken down. They love it. But there is one thing they love more: redemption stories. And I hope for that for Vince. I hope for some possibility that he might rise from the ashes.”

Fumo still has a desire to be involved. Incredibly, the phone number for his old Tasker Street Senate office still rings — ported over to his mansion, where Veasy answers, “Senator Vince Fumo’s office.”

Fumo even emailed, shortly after our last scheduled interview, and asked me to come back, saying he wanted to show me “charts and maps.”

When I do, Fumo pulls out some maps, old curios from his time in the Senate office. In the late ’90s, Fumo had his staff go out and map the whole neighborhood, crafting a color-coded chart of every house and building. Green areas were denoted by his team as healthy, and red ones showed problem properties — blighted and abandoned buildings. The first map, produced in 1999, shows big swaths of red. Then Fumo, through his staff and the various agencies with which he intersected, including Citizens Alliance, started accumulating and rehabbing properties there and throughout Spring Garden, as he also did in East Passyunk.

“Now look at this,” Fumo says, and reveals a second map, from 2007, showing the area covered almost entirely in green.

Fumo talks excitedly about how the initiative also served as a kind of cash pump — bringing in revenue from renting those rehabbed properties — and for a while, it looks like he called me back to enjoy a 10-minute nostalgia trip. But then he adds something new, another area of the city that he’d target for the same treatment.

He started thinking about this area, he says, years ago. But recently, he took a scouting trip, circling the blocks around the old, unused Amtrak station in North Philadelphia, to check it out more closely. And in a few minutes, he lays out his plan: “Get Amtrak on board. See if they might reopen the station for just a couple of stops per day to bring some life to the area.”

A team of New York developers has since announced a plan for new buildings in the area, though there has been no word since spring if they are moving forward. Fumo’s plan is different, and harks back to his earlier redevelopment efforts: Use an existing nonprofit or start a new one and raise some funding, accumulate some properties, and do what he did in Fairmount and Passyunk: rehab and rent to the same kinds of entrepreneurs who flocked to Passyunk when Citizens Alliance started its work there. “I think it could be fantastic,” says Fumo.

It’s an unseasonably warm September day, and Fumo is dressed in crisp blue jeans and a light blue button-down shirt. He’s at his desk, and he suddenly leans back and stares around, a little wild-eyed again, and says, “You know, it’s funny. … ”

He had dinner with someone the other night and found himself talking about this would-be neighborhood, laying out his plan like he might actually make it so.

Cipriano, Fumo’s biographer, swung by to talk about their upcoming book, and he interjects a question: “This is the kind of thing Kenney could take you in to advise on, right, and make him look great?”

“Yeah,” says Fumo, who then frowns and stares off for a moment into the middle distance — just an old man hidden in the bowels of his mansion, where all he can do is envision the long list of things he might have done, but never will.

Published as “Vince Fumo Would Like To Be Vince Fumo Again” in the December 2017 issue of Philadelphia magazine.