Breaking Down

Illustration by Mario Zucca

I’m sitting in the driver’s seat of my 2006 Honda, saying a little prayer. I’m not, under ordinary circumstances, a praying person, though when my kids were small I never merged onto the Schuylkill Expressway without thinking, “Please, God, just let me live to see the children again.” But the odometer on the Honda reads 209,468 miles, and a prayer seems in order. So I say it: Please, God. Not today.

I’ve had the car — it’s an Accord, gray, with a little red pinstripe — for so long that it feels like my second body, my exoskeleton. I didn’t love it when we bought it. Quite the contrary. I had to trade in my big old boat of a Mercury station wagon to get it, and even though the Mercury never steered right and needed constant realignment and was chipped and battered, it held golden memories of Girl Scout camping trips and summer vacations to the Outer Banks and lazy walks with the dog down by the riverside. That poor dog never got the hang of jumping into the Honda; he banged his head every time he tried. He was old by the time we bought it (used, with 50,000 miles already on it), and riddled with cancer. We had him put to sleep just a month or so later. For a long time, I blamed the Honda for that.

The Silver Boat stood for the open road, and freedom. The Honda stood for back to work full-time.

There’s nothing fun about this car, or sexy. It’s the automotive equivalent of Hillary Clinton. And as with Clinton, I only came to appreciate it slowly, begrudgingly. One flat tire in eight years. Not a single major repair. Just getting the job done, day after day after day, for 37 miles each way into Philly and back on what are some of the worst, most congested roads in the nation. A workhorse. A trouper. Salt of the earth.

And any day now, something’s gonna go. On any given morning, I could be That Lady, the one in the broken-down jalopy in the center lane of the Schuylkill Expressway, sitting silent and shamed while my fellow drivers curse at me and lines of vehicles stretch out behind me for miles.

I DON’T KNOW enough about cars to even guess what might go first in one with this many miles on it. I’ve owned a lot of cars, but none ever came close to my Honda’s level of longevity. I wish Click and Clack were still taking calls on Saturday mornings on NPR, so I could ask them: What do you think will be the cause of death? I’d like to hear them laugh and argue about it while they toss around mysterious terms like differential and transaxle and rack-and-pinion. They’d probably tell me to get another car, a newer one, stat. Which I’d be happy to do, except right now, like most of America, my husband and I are in a hell of a crunch, just barely making the payments we already have, between college and the mortgage and the taxes that go up and up and a wedding later this summer. Another car payment — even a used-car payment — will tip us right into financial oblivion. Which is why every time I get into my car, I pray. And why, when I wake up in the middle of the night, I lie in bed and can’t get back to sleep as my mind spins out endless skeins of what ifs: What if the furnace breaks down again? What if the refrigerator finally goes? What if I get laid off? WHAT IF THE HONDA DIES?!?

In the dark, in the night, I listen to my breathing, and the drum of my heartbeat. It’s a lot like the way I listen to the Honda as I drive it, turning down Taylor Swift or KYW to wonder: Is it slipping a little between first and second gear? What’s that high-pitched whine? Spring rolls into summer, the windows go down, and I’m panicked by a whole new set of creaks and groans.

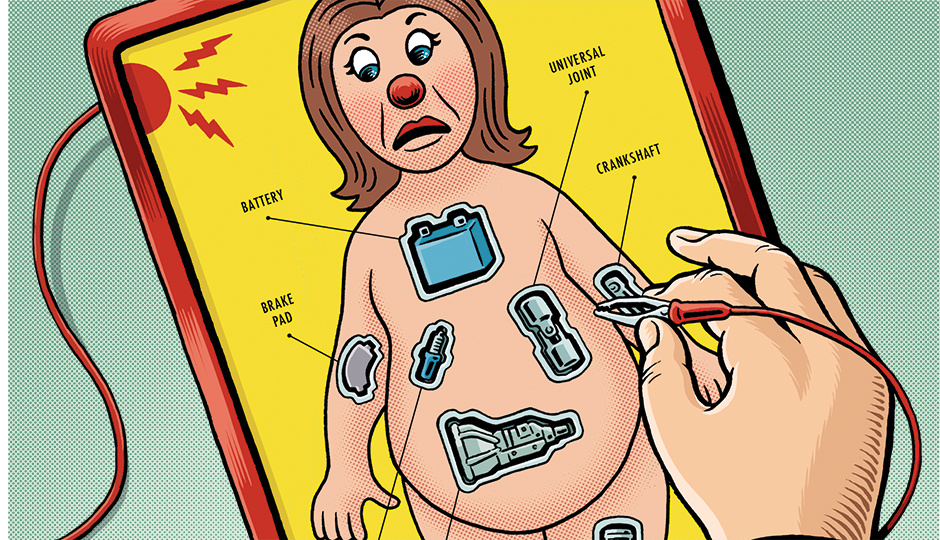

The car isn’t the only thing creaking and groaning. The nine years I’ve owned it coincide with the stretch of time in which I’ve gone from feeling pretty much on top of my game physically to feeling, well, apprehensive. I turn 60 this fall, and every new checkup at the doctor seems to add one more daily med — for blood pressure, blood thinning, arthritis, cholesterol. The gang I’ve played volleyball with on Tuesday nights for a decade has gotten much grayer, and slower. Members of my pickleball crowd at the Y disappear for weeks, even months, at a stretch, then show up again on crutches, with new hips or knees. They fight their way back onto the court — or don’t. We’re all like the Honda now, one major problem away from disaster. What will go next — the heart? Rotator cuff? Memory? (Why is pickleball scorekeeping so complicated?) I have a lot of miles on me, too. I climb out of bed in the morning like the Tin Man, gingerly checking my joints as I stagger to the bathroom for ibuprofen. I have a hard time getting from first to second gear.

There was an article in the New York Times the other day about something called the R70i Age Suit. It’s a robotic contraption designed to let young people experience what it feels like to be old, so they’ll have more empathy instead of just despising us. The R70i blurs your vision, distorts your hearing, weighs down your limbs, inhibits the movement of your joints. “[I]n just 10 minutes,” the author wrote, “the aging suit induced a remarkable amount of frustration, depression and hopelessness.” Oh, joy. I can’t see the kids next door turning cartwheels or jumping on their trampoline anymore without being riddled with regret: Why did I never climb the Rockies? Run a marathon? I would have done so much more had I known how soon all of that would be taken from me. I’m like the damned dog, expecting the same old thing to work as I jump into the car, only to find that the landscape has changed. But it isn’t the landscape. It’s me.

MY CAR, OF COURSE, is the opposite of the R70i Age Suit. When I drive it, I’m 21 again, limber and fierce. I think, often, of how my dad kept driving down to Florida for the winter long after my siblings and I thought it was safe for him to do so. I’m starting to understand how hard it will be to relinquish my keys.

Not too long ago, a young man plowed into the back of my Honda. I wasn’t on the Expressway, or driving in Center City. I was in the middle of nowhere, on a back street in sleepy Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania, making a left into the train station parking lot. The young man told me he’d glanced over at the apartment complex he and his girlfriend were about to move into together and didn’t see me stop. That was rather romantic, I thought.

He was such a nice, polite young man. And as it happened, he was an auto mechanic. While I sat and waited for my husband and son to come and check out the Honda, I watched him take off his whole front bumper and tie it to his roof. My back bumper was badly dented, but I could drive the car home. The Honda would live to see another day.

The bumper had to be replaced, though. I lined up a rental, and a cheerful young lady drove it to me at the auto-body shop. I climbed into the driver’s seat, and she crouched down beside me with the door open, ready to give me a quick tutorial on this 2016 model.

“It’s keyless entry,” she said brightly.

I started to cry.

Why? Why was it keyless entry? What was wrong with using a key? The dashboard looked like the control panel of a fighter jet. There were so many screens and dials and buttons that I couldn’t even imagine where to begin. Who knew cars had come so far in a decade? The young lady eyed me dubiously. I couldn’t stop sobbing. This car felt like the farthest thing from home; it was alien, horrible, inscrutable. I’d never make it to Philly in this thing.

“Don’t worry. I’ll be all right,” I told the young lady gamely, through gritted teeth. I’m sure she still laughs about me with her friends.

The mechanic at the auto-body shop was more perceptive. When he came outside to look the Honda over, he eyed the bumper and then the long scrapes running along each side. “We taking these side panels off?” he asked.

I shook my head. “Those are courtesy of the guys at the garage where I park in Philly. Just the rear bumper is all I need replaced.” He went around to the back of the car again. A lot of history had been written across that bumper well before Elizabethtown: two kids learning to drive, hundreds of whacks from shopping carts, all the dents from me trying to parallel-park in front of our house. You’d think I’d have the hang of that telephone pole by now, after 22 years.

“It has more than 200,000 miles on it,” I said by way of explanation, since he was clearly offended that I wasn’t having those side panels fixed. (Hey, he’s an auto-body guy.)

He nodded, thoughtfully. “This car doesn’t owe you anything, does it?”

That’s it, exactly. The car doesn’t owe me anything. Every mile I put on it from here on out is a gift, a mitzvah from the Honda to me.

THAT’S PRETTY MUCH how I’ve come to feel about my body — my failing, arthritic, no-robot-suit-necessary-thank-you body. I never expected to live this long, frankly. My mom died young, and so did her mom, both of their lives cut way too short by cancer. By their standards, I’ve been in overtime for years now. The extra innings. Free life. More than I deserve.

Meanwhile, I’ve decided what’s going to go on the Honda is the universal joint. I don’t have any idea what a universal joint is or does, but it sure doesn’t sound like something you want to have give out. Especially in morning rush hour, on the Schuylkill Expressway. What goes won’t be particular; it will be huge, cosmic, all-encompassing. I can picture the tow-truck guy now, peering under my hood and shaking his head, chewing on a toothpick: “Yup, that’d be your universal joint. It’s completely blown.”

And that will be the end of the Honda. I’ll have to learn my way around a new car. Hopefully it won’t have one of those terrifying rear cameras to help you park, like that rental did. I kept expecting to see Pac-Man pop up between those green lines. Eh, whatever. I’ll deal. I’ll adapt. Maybe I’ll stop hitting that telephone pole. Life is growth and change, right? We get to rest when we die.

For now, I just keep driving. What other choice do I have? I could make 250K. I could make it to 65, maybe even 70. The Phils won in extra innings today. We’ve got a wedding in August. Every mile, every day a mitzvah. Like the man said, life doesn’t owe me anything.

Published as “Crankcase” in the July issue of Philadelphia magazine.