11 Things You Might Not Know About Betsy Ross

Happy Flag Day! Now, let's get down to it—did she or didn't she?

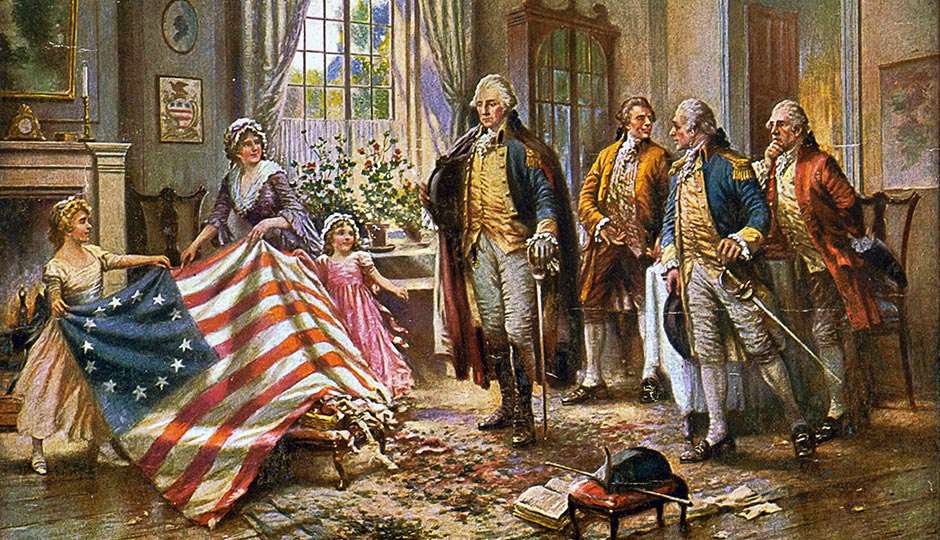

Painting depicting the story of Betsy Ross presenting the first American flag to General George Washington, by Edward Percy Moran. Public Domain.

Today is Flag Day, commemorating the date in 1777 on which the Continental Congress passed a resolution that read: “Resolved. That the flag of the United States be 13 stripes alternate red and white, that the Union be 13 stars white in a field of blue representing a new constellation.” It wasn’t much to go on — which came first, a white stripe or a red one? What shape was that “new constellation”? — and it isn’t really clear whether the legislators intended this new flag to be the flag, or simply a flag. (The resolution came from the Marine Committee.) But this is America, and hey, we never let a little uncertainty stand in the way of a great myth, which is how we come to Betsy Ross. Did she make that flag, or didn’t she? Here are 11 things you might not know about our famous First Seamstress.

- Betsy, née Elizabeth Griscom, was born on New Year’s Day 1752 in Gloucester City, New Jersey, the eighth of the 17 children of Samuel and Rebecca James Griscom. Only nine of the children survived to adulthood; two siblings died before Betsy was born; one sister died when she was five and another when she was seven. Two brothers, both named Samuel, died when Betsy was four and 15, respectively; three-year-old twins died when she was 20, during a smallpox epidemic. Such domestic carnage wasn’t unusual for the time.

- After attending a Quaker school, Betsy was apprenticed to an upholsterer named William Webster. While working for him, she fell in love with fellow apprentice John Ross, a nephew of George Ross Jr., one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. John and Betsy eloped and were married in Gloucester City, New Jersey, when she was 21.

- The Griscom household was Quaker; the Rosses were Anglican. After her elopement, Betsy was expelled from her Quaker congregation and shunned by her family. She and John started their own upholstery business in Philadelphia and joined Christ Church near 2nd and Market, where George Washington worshiped when he was in Philadelphia on business.

- Two years into the marriage, the Revolutionary War broke out. John, who was a member of the Pennsylvania Provincial Militia, was assigned to guard munitions and was killed in a gunpowder explosion. Betsy, widowed at 24 and with no children, continued the upholstery business in a shop on Arch Street while also making tents and blankets, repairing uniforms and constructing musket balls for the Continental Army.

- Some historians theorize that Betsy was the “beautiful young widow” who served to distract Hessian Colonel Carl Emil Ulrich von Donop by spending Christmas Eve 1776 with him and diverting him and his troops from Washington’s successful assault on Trenton on Christmas Day. If so, she took one for the troops; von Donop was brutal and harsh and disliked even by his own men.

- On June 15, 1777, Betsy married her second husband, seaman Joseph Ashburn. In 1780, Ashburn’s ship was captured by the Royal Navy; he was charged with treason and jailed in Old Mill Prison in England. While he was there, his first daughter with Betsy, named Zilla, died, and another daughter, Eliza, was born. He died in Old Mill in 1780, and a fellow prisoner, John Claypoole, brought Betsy the news. Three years later, she married Claypoole. They went on to have five daughters together: Clarissa, Susanna, Jane, Rachel, and Harriet, who died while still a baby.

- Betsy’s mother, father and sister Deborah all died in Philadelphia’s 1793 yellow fever epidemic. John Claypoole died in 1817. Betsy, who had worked all along as an upholsterer and seamstress, kept her shop open for another decade after his death before retiring because of poor eyesight and moving in with her daughter Susanna on a farm in Abington Township. Her daughter Clarissa took over the shop, which may or may not have been situated where the current Betsy Ross House stands, at 239 Arch Street.

- The first mention of Betsy in conjunction with the sewing of the Stars and Stripes is in a paper written by her grandson, William Canby, and presented by him to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in March of 1870. The paper relies on family recollections from Betsy’s daughters and a cousin to recount the now-familiar tale of how George Washington, with several other founding fathers, visited Betsy in her shop and commissioned her to sew the first true American flag. In Canby’s story, Washington originally wanted six-pointed stars on the flag because they were easier to cut, but Betsy demonstrated to him a quick, simple method of cutting a five-pointed star with a single scissors-snip. The U.S. government provides a slide show demonstrating the technique; it’s completely unintelligible. (Surprise!) This private version is much clearer and easy to re-create. (Rainy-day fun!)

- Until very recently, there was no documentary evidence for this charming story except for a receipt showing that Betsy was paid to sew a naval ensign for a squadron of U.S. ships. Canby’s account was nonetheless popularized in magazines and books. Five years after it appeared, another relative, J. Franklin Reigart, published a book that further embellished the tale. In these Victorian versions, Betsy is a prim and proper mob-capped seamstress rather than a businesswoman who kept her upholstery shop going through times of war and epidemic, outlived three husbands and raised five daughters. Historian Marla Miller, author of a biography of Betsy, once told the City Paper, “There was an effort in the late 19th century to make her a domestic figure when, as we know, she had this upholstery shop. … There’s a clear effort to pull her out of the labor history context where she really belongs. The culture has never imagined her working, stuffing a mattress or doing the work we knew she did.”

- For the five years she lived in Abington, Betsy rode a carriage into the city every week to attend the Free Quaker Meetinghouse at 5th and Arch streets. She spent the final years of her life back in Philadelphia, completely blind, living on Cherry Street with her daughter Jane’s family. She died in her sleep on January 30, 1836, at the age of 84. She was buried in the Quaker burial ground near 5th and Locust, but her remains were moved to Mount Moriah Cemetery in 1857 before being brought home to a courtyard adjacent to the Betsy Ross House in time for the Bicentennial, in 1975.

- In March of 2015, the associate curator of Mount Vernon, Washington’s Virginia estate, unearthed a receipt for 55 pounds, 12 shillings and sixpence — a hefty sum of money — made out to one “John Ross of Philadelphia” for the linens for three beds, including canopies, sheets and covers, made from cotton calico and lined with muslin. The only John Ross in Philly at the time was Betsy’s husband. Historians favoring the story of Betsy and the flag hailed the discovery; as the associate curator, Amanda Isaac, said, “It’s the only documentation we have that these two icons of the American Revolution, Betsy and George, actually met. Before, it was all mythology.”

Follow @SandyHingston on Twitter.