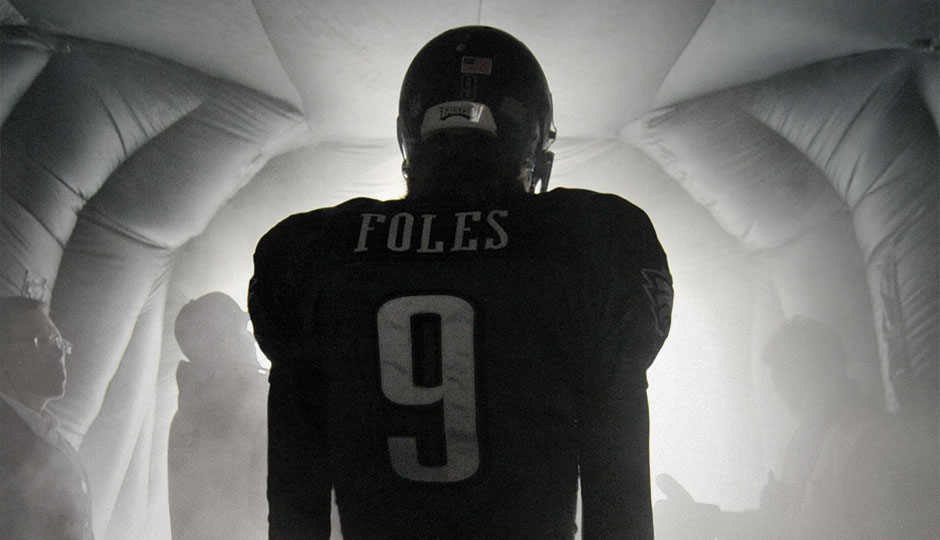

Who Is Nick Foles?

OK, so, we were a little early with this back in 2014 — but the second time is clearly the charm.

Photograph by Nick Hallowell/Getty Images

Within the physical layout of Westlake High School is a space referred to as the Commons, with an insignia of a W in the middle of the floor. It was a hangout for seniors when Nick Foles was in his final year there in 2006. In the social pecking order at Westlake, the cooler you were, the more you gravitated to the middle.

That was the observation of Bron Hager. Hager was a latecomer to Westlake, which is located about 20 minutes west of downtown Austin. He had transferred in as a junior from a small private school, and the transition hadn’t been easy. Maybe he was too obsessed with cool, and the middle of the Commons was, well, the middle of the Commons. But Hager noticed something else about the middle: the one person who never wanted to be there.

In a school of remarkable achievement and affluence, Nick Foles perfectly fit the Westlake socioeconomic profile and was its BMOC. He was the quarterback of its football team, the Chaparrals, on their way to the Texas state championship game in the highest 5-A classification. He was equally gifted in basketball; he’d started as a freshman. His girlfriend, Lauren Farmer, was a standout cheerleader and homecoming queen. Nick Foles was the middle.

But Foles pawed around the edges. The only middle he was interested in was a football huddle, and even there, he led by the example of his toughness and arm, which gave receivers chest bruises. He cannoned balls 60 yards flat-footed, and had stand-up pocket presence. He never yelled. The idea of him trash-talking was unthinkable. He had an almost pathological aversion to drawing attention to himself, as if it was sinful. He didn’t have the requisite personality for it, anyway.

The truth was, Nick Foles was something of a nerd, a guy who hung around with a small posse of mostly non-football nerds — eggheads, kids who would go on to careers in finance and private equity and engineering. A hot Saturday night was getting together at his house to play video games like Call of Duty, or hanging out at Zilker Park on the shores of Lady Bird Lake. “Dude, come on, you’re the quarterback, go out and have some fun,” high-school teammate Matt Nader pleaded with him, fruitlessly.

He was the kid you wanted dating your daughter, because he would have her home at 9:30 after you said 10. He was socially awkward, with a naive and goofy sense of humor. He dressed as if he had never seen clothes before. His hair was oddly styled in an ersatz pageboy, curling below his ears like a drainage ditch and covering his forehead in uneven wisps, thin grime on a windshield. His face was a cup of Napoleon Dynamite and a tablespoon of golly-gee-willikers and a teaspoon of Gomer Pyle. He tried at school, and even took Latin.

During his senior spring-break trip to Mexico, while most everyone else spent the afternoon recovering from drinking, he jogged, because there was nothing for him to recover from. He threw a football around with a kid from the Austin area. When Nick asked the kid to name his favorite player, he said, “Nick Foles!” But the kid didn’t recognize that he was having a catch with the actual Nick Foles. And Nick Foles was too reticent to tell him.

THE NICK FOLES of today still bears a great resemblance to the Nick Foles of yesterday. The teeth are whiter; the hair is shorter; he sometimes wears Hugo Boss. Earlier this year he married former University of Arizona volleyball player Tori Moore — brunette, built, beautiful — and he even held a glass of champagne when he got engaged. But he is still quiet. He still leads by example. He still plays video games. He still wears the hair suit of humility. He still pathologically refuses to do anything that draws attention to him. It’s admirable. Actually, it’s boring. It’s unrealistic and annoying now, self-subsumption as a form of conceit.

When in only your second year, at the age of 24, you complete 64 percent of your passes for 2,891 yards and 27 touchdowns, with only two interceptions and a quarterback rating of 119.2 that’s better than every other National Football League quarterback, you’re going to garner attention. Fans, understandably, are going to want to know more about you, particularly since you’re still a mystery. It’s part of the territory. You’re in the pros. Deal with it.

I asked Nick Foles for an interview for this story. My request was rejected. According to his agent, Justin Schulman, Foles doesn’t want to do anything at this point that highlights his success and not the team collectively. Uh, it’s a little late for that, son, given that you’re the hottest-rising quarterback in the NFL. You are the attention draw.

I was asked to do the story because of the enormous common bond that Foles and I share: Texas high-school football. He’s defined by it, and I memorialized it in the book Friday Night Lights. The request for his time went from a couple of days to a couple of hours anywhere in the country. This story isn’t about wrenching sensitive secrets. It’s obvious and legitimate.

Particularly since Foles is the New Face of Philadelphia Sports in a sports-mad town, the newest promise to the Promised Land in the post-Donovan McNabb era. Is he capable of leading the Eagles to the Super Bowl one day? Was the 2013 season aberrant? How will he handle the pressure? Fans need to try to figure out what ticks inside him to remotely know any of the answers.

Instead, what has emerged is a one-dimensional choirboy caricature reflective of a player and a team and a league terrified of individuality. Foles is selling himself, and being sold by the born-again Eagles, as the anti-DeSean: contrite, non-charismatic, cautious, churchgoing, Caucasian. The perfect poster boy for Eagles owner Jeffrey Lurie and commissioner Roger Goodell’s vision of a new NFL theme park where players have no discernible personality and the Twitter account is laced with Glories to God.

I don’t believe this is all there is to Nick Foles. I definitely don’t believe it after spending extensive time in Austin talking to teammates and coaches and parents in the roots of Texas and high-school football that so define him. I now realize how different he is from every other player in the NFL. He has been forced to overcome much adversity on the football field and none off of it, because he grew up in a cocoon virtually devoid of African-Americans and poverty and hardship. He shares an economic background similar to that of fellow Texas product Johnny Manziel, only with a much richer family and without any of Manziel’s presence. And in a key defining moment in his life, perhaps the key moment, he was bearing witness to something that no one should ever have to see.

TO KNOW NICK FOLES, you go back to the base. Which means going to the community that encompasses Westlake High School. Its predominant zip code, 78746, is an Austin equivalent of Beverly Hills, 90210. Its population of some 27,000 is small and homogeneous and oppressively white. It’s an area where everyone pretty much melds into everyone else to create one big blob, men in button-downs or polo shirts with the insignia of the golf club like a one-percenter skull head, women trim and prim and pretty in the way that dressed-up mannequins can be. There is no downtown, as if the very idea is somehow creatively dangerous, too much expression. The median house value in 2011, $610,800, is roughly five times the Texas average. The median family income of $167,295 is almost three times the state norm. There are 82 families who own five or more vehicles, and 1,251 who live in homes with five or more bedrooms.

Foles’s spawning ground, Westlake High, was born out of the age of forced integration in the 1950s and ’60s, in the wake of Brown v. Board of Education. Before the first year of classes at Westlake, in 1970, high-school students in the Eanes Independent School District were still being bused to Austin, since they had no high school of their own. When the area was faced with the choice of either joining the Austin school district, which would have meant forced integration of its schools, or remaining independent and building a high school, the answer wasn’t terribly surprising. The minority population of Westlake High in 2010 was roughly 18 percent. Of that, only one percent were African-American. Foles didn’t have a single black teammate when he played his senior season in 2006.

This says nothing about his or anyone else’s racial attitudes. It does say that Foles grew up in a bubble of entitlement and shockingly narrow social experience. “Nick was a privileged guy,” says Hager. “The guy had whatever he wanted.” So did pretty much everyone else. Only three percent of the roughly 2,500 students at Westlake are listed as economically disadvantaged, compared to the Texas average of 60 percent.

A large number of students at Westlake are the sons and daughters of lawyers and doctors and high-tech capitalists and private equity managers and business executives. The car of choice in the student parking lot is the Lexus. These are the overachieving kids of overachieving parents who pay gargantuan taxes, which is why the district superintendent makes $240,306 and the principal $140,000 and the football coach/athletic director $109,980 and the director of the band $94,800. Which is also the reason the school is superb academically, one of Newsweek’s best 100 in the nation, with a mean SAT score of 1214. Which is why Foles’s teammates went off to schools like Harvard, Princeton, Dartmouth, the University of Virginia and the Air Force Academy. It’s also why Westlake is reviled in Central Texas for being rich, snotty and white.

Other high schools don’t like Westlake, which lends a subtext of racial war to some of the football games it plays. The antagonism is further stirred by the legacy of the Westlake Chaparrals, undersized players who outsmart and out-condition opponents. The school won a state championship in 1996 under Drew Brees, has been to the finals seven times, and won its district 18 years in a row. And never lost to archrival Austin High until, somewhat ignominiously, Foles was a senior. The school had four players in the pros last year — Foles, Brees, Baltimore Ravens kicker Justin Tucker and Tampa Bay Buccaneers tight end Kyle Adams. That’s the most of any high school in Texas.

No one will ever say that Nick Foles is snotty. But he is obviously white, and his family is rich — very rich, well into the many millions, based on Securities and Exchange Commission filings. It isn’t farfetched speculation to think that he comes from the richest family of any player in the NFL.

His high-school teammate Matt Nader tells me that the best way to assess the rising fortunes of the Foles family was by observing the improvements made to their house over the years. The 6,708-square-foot mini-mansion, with a pool and spa, is in the winding Candylandesque hills off Westlake Drive, at the end of a cul-de-sac in an upscale housing development where even the flower petals fluttering onto the Elysian lawns look purposely placed. Currently assessed at $1.5 million, it was hardly a rancher when the Foles family bought it in the late ’90s. But over the years, the basement was finished and a new garage was put in, according to Travis County appraisal records. Then came the uncovered deck and a first-floor porch almost the entire length of the house.

The money was made by Foles’s father, Larry. Said to be a man of sober seriousness and infinite ambition, he has had remarkable success in the brutal hit-and-mostly-miss field of restauranteering. His son has inherited his relentless work ethic; during June and July, when Westlake players work out on their own, it isn’t unusual for them to hit the weight room. Teammates watched agape as Nick Foles toiled in an hours-long regimen of throwing and running in the lugubrious Texas heat.

It was Larry, better than any coach or recruiter or pro scout, who knew how good Nick could be if he was pushed. So Larry pushed, perhaps because his whole life has been about pushing. He was the kind of parent who tried to make not only every practice at Westlake High, but also every junior-high practice. As fellow Chaparral parent Paul Nader says, perhaps euphemistically, pushing sometimes meant “tough love.” Bron Hager says that Larry was always ready to go to war for Nick, but war of course is never pretty: “He’s Nick’s toughest critic.” Hager remembers sitting next to Larry at the Arizona-USC game in 2009: “There wasn’t a more-pissed parent.” (Nick threw for 239 yards and two touchdowns, including the game-winner late in the fourth quarter.)

Raised in Petal, Mississippi, Larry Foles had nothing growing up. He told hiladelphia Daily News Eagles beat reporter Les Bowen (Larry Foles and his wife, Melissa, also declined to be interviewed for this story) that his parents split when he was 13, prompting him to drop out of high school and move to Oregon in the early ’60s to work manual labor for 90 cents an hour. He returned to Mississippi and became the general manger of a Shoney’s.

Then he went into the ownership side, with partner Guy Villavaso. The two became a hit parade, using Austin as their incubator. Their greatest accomplishments — Eddie V’s Prime Seafood Grille, with eight locations, and Wildfish Seafood, with three — were sold along with the brands in 2011 to the huge conglomerate Darden Restaurants for $59 million in cash.

Larry Foles seemed to view his son’s college career the way he did a restaurant: location, location, location. If one fails, you move and try someplace else until something works. When Nick signed a letter of intent with Arizona State University before his senior season, it was Larry who made initial contact with the school, as opposed to the other way around. When Nick decommitted from Arizona State and went to Michigan State University in 2007, Larry got an apartment in East Lansing. When Nick was deciding whether to leave Michigan State after a year, it was Larry who became his spokesman. When Nick then went to the University of Arizona, it made sense because of Larry’s significant restaurant holdings in the state.

Nick’s deep sense of faith and generosity of spirit to others come from his mother. When Hager, the son of former Eagles linebacker Britt Hager, came to Westlake, he hated the school, and the school hated him back. Foles reached out to him, befriending him without noblesse oblige, opening up his home to him and making him feel part of something.

“He’s just a very down-to-earth guy,” says Justin Wang, who was a kicker on the team and Foles’s best friend in high school, part of that quasi-nerd posse. “We’re not quiet people. We’re people who like to hang out. We were just never into going crazy and partying all the time.” Hager did manage to corrupt Foles just a bit, late in their senior year: Foles conducted an ultimately losing battle with cognac and vermouth and ended up facedown on the carpet, mumbling incoherently to his girlfriend on his cellphone.

It seems doubtful it has happened since.

Which is a shame.

THE GREATEST ATHLETES all have arrogance; no matter how thick the playbook of humility, it still seeps through. You can see it and you can feel it. Except with Foles.

“Every time I ask him how things are going, it’s always about the team,” says Wang. “All this success hasn’t changed who he is.”

Michael Vick is a great guy. It was an extraordinary team effort. The offensive line deserves all the credit.

Give it a little bit of a rest, kid.

Nobody can deny Nick Foles’s toughness, at six-foot-five and 240 pounds. He played the last 12 games of his senior year at Westlake High with a torn labrum in his throwing shoulder without telling anyone or complaining about the pain.

But there’s still an aura of softness about him, no fire. Maybe it’s the hee-haw face. Maybe it’s the stream of selfless platitudes about others. Maybe it’s that at 25, he’s still very much a boy among men with the Eagles, with no interest in the extracurricular world of clubbing. Or maybe it’s the reality that if he fails in football, he has the likely cushion of going into an enormously successful family business. It’s the intangible hunger factor that appears to be missing.

There is some danger in judging Foles from his outward temperament. Derek Long, Foles’s former head coach at Westlake, believes he’s far more observant than he ever lets on. High-school teammates describe an inner confidence hard to pinpoint, but always there.

The most consistent element of Foles’s career has been doubt about him: He has never succumbed to discouragement, even though he’s had plenty of it.

It goes back to his sophomore year in high school, when he was being groomed to be Westlake’s starting quarterback. Foles was also an excellent basketball player, with a chance of playing Division I. He wasn’t sure about his degree of commitment to football in a program that, as with all Texas high-school football, doesn’t welcome indecision. Teammates remember him being hurt a lot of the time. “What’s the deal with Foles?” was the sentiment of wide receiver Staton Jobe. “Is he going to be injured his whole career?” Adds head coach Long: “We felt like he was going to be able to step in, but we weren’t sure. … We knew he could throw, but there’s a lot more to being a quarterback.”

Then Foles, who has a pattern of reducing expectations to nothing only to exceed them since there no longer are any, stepped it up. He started as a junior. He became a star in Texas. His senior year, he led Westlake to the state championship finals against Southlake Carroll, which was undefeated and ultimately named the top-ranked team in the country. Westlake actually led at the half, 15-7, on its way to a major upset. But then, early in the second half, came a most unusual play that not even Chip Kelly has installed and that bears mentioning:

Southlake Carroll quarterback Riley Dodge, operating out of the shotgun, projectile-vomited right before the snap. This stunned the Westlake defense (talking about it today, some players still seem stunned), which resulted in Dodge throwing a touchdown pass. Westlake was never the same after that and lost, 43-29.

Foles broke the career passing-yardage record at Westlake held by Drew Brees, throwing for 5,658 yards. But he wasn’t a hot recruit. The rap was that he was too slow, a system quarterback in a school that has produced nine quarterbacks who have gone on to play that position in college football since 1992 — at best, he was a backup. Plus, it was the age of the dual threat and Vince Young. Duke made an offer, which back then was slightly better than being chosen last in a pickup game. Texas El Paso sought him out, which was the Gulag. The major Texas schools weren’t interested. Signing with Arizona State became a mess when the coach who wanted him, Dirk Koetter, was fired and replaced by Dennis Erickson, who in turn was so impressed by Foles that he went out and recruited another quarterback.

After walking away from Arizona State, Foles signed late in the recruiting season with Michigan State. He got into the first game of the season in 2007, and that was all. He was homesick and going through a bad breakup with his girlfriend. He was competing with Kirk Cousins (a redshirt) and Brian Hoyer, both future pros. Before his sophomore season, head coach Mark Dantonio signed quarterback transfer Keith Nichol. And Foles was on the move again. “I didn’t think he was going to make it,” says Hager. “I don’t know where he got his strength to make it.” Adds Justin Wang: “He just took it in stride. His faith allowed him to stay strong.”

Foles transferred to Arizona. He battled with Matt Scott for the starting job and lost it, until Scott played poorly and Foles got his chance. The team went to two consecutive bowl games under Foles, in 2009 and 2010. His senior year was a team disaster. He put up great numbers, throwing for 4,334 yards and 28 touchdowns. But Arizona won only four games. Head coach Mike Stoops was fired in the middle of the season.

The newest rap was that Foles had played in a gimmicky offense with few sophisticated reads. But he was named to the Senior Bowl and, in his typical pattern, was so lackluster in practices that several draft experts showered praise instead on Brandon Weeden. Foles then played, with the best performance of any quarterback, and was thought to be a possible first-round pick. Then he made the single worst mistake of his career. He entered the NFL combine.

THE COMBINE IS A monument to the absurdity of how NFL teams judge college players, depending on the 40-yard dash and the vertical leap and the broad jump as if actual game experience is irrelevant. It is also beyond demeaning, with pasty-looking men in over-saturated polo shirts and guts that spill well beyond the belt line timing the specimens and whispering conspiratorially to each other like bidders at a horse auction. The only thing they don’t do is open up mouths with thumb and forefinger to inspect teeth, followed by spreading the cheeks for signs of unauthorized use.

Among quarterbacks entering the draft in 2012, Robert Griffin III ran the 40-yard dash in 4.41, Russell Wilson in 4.55, Andrew Luck in 4.67 and Ryan Tannehill in 4.62. Foles’s time was 5.14 seconds — the worst of the quarterbacks who entered. Pro Football Weekly called him a “lumbering pocket passer” who gets “panicked in the pocket” and said he “is consistently off the mark” and “is not an inspiring field general,” on a par with former fifth-round pick John Skelton of the Arizona Cardinals. But former Eagles coach Andy Reid and offensive coordinator Marty Mornhinweg saw something in Foles that no one else did, and they drafted him in the third round.

Foles played in seven games in 2012, starting six of them because of a Michael Vick injury. He put up mediocre numbers typical of a rookie. “Everything was clouded by Michael Vick,” says Nader, recounting the ensuing chatter. “‘He doesn’t belong here.’ ‘He doesn’t belong in this type of offense.’ ‘Who is Nick Foles?’”

He was the same Nick Foles who a year later threw for an NFL record-tying seven touchdown passes against the Oakland Raiders and came out of nowhere to be the league’s phenomenon.

Foles still doesn’t inspire full faith among fans. He shouldn’t. One-year wonders in professional sports form an endless chain. He was unknown last year, and the unknown is often a player’s best asset until it becomes known. When Chip Kelly talks about Foles as the franchise quarterback, it always feels like he’s lying, because he’s both good at it and a smug wiseass.

Foles isn’t a pressure quarterback. He lost the state championship in high school, lost both of his bowl games, and looked confused in the second half of the loss to the New Orleans Saints in last year’s playoffs. In 17 pro starts, he’s thrown only one game-winning touchdown pass in the fourth quarter or overtime. (Compare that to Andrew Luck, who threw six in his first two seasons.) Sometimes he just flings it up there in the hope that someone is around to catch it, although without DeSean Jackson, that’s become far less likely. The Eagles also played a weak schedule last year.

And yet.

IT WAS HOT that September night in 2006. When people talk about what happened, this is the first thing they invariably mention — how hot it was.

The game-time temperature in College Station was 88 degrees, with 52 percent humidity. Playing football in the heat is unbearable. But there’s something about Texas heat that makes it even more unbearable.

Not that it particularly mattered. Westlake came into the game undefeated and ranked sixth in the state. Its opponent, A&M Consolidated, was undefeated and ranked number four. It was the game of the week in Texas.

There was buzz about Foles. But in terms of future college potential on Westlake, offensive tackle Matt Nader caused much more excitement. Nader was six-foot-six and 300 pounds, and he pretty much threw defenders around at will. He also had astounding lateral movement for a player that size, and may have been faster than Foles. Nader had been second-team all-state as a junior, and was so talented that he had already committed to the University of Texas. Mack Brown wanted him badly.

A&M scored early in the game to take a 7-0 lead. Westlake came back with a 16-play drive that consumed roughly seven minutes. As Paul Nader and Barbara Bergin — he a nephrologist, she an orthopedic surgeon — watched their son, he seemed uncharacteristically sluggish, not firing off the line, even getting tossed around a little bit. They figured it was the heat, or maybe nervousness.

Foles and Nader came off the field. Nader went to the bench with the other offensive linemen. Offensive line coach Steve Ramsey came over to critique what had gone right and what had gone wrong during the drive. An ice towel was placed on the back of Nader’s neck. He suddenly fell and landed on his back with his cleats still propped up on the bench. It was so bizarre that Hager thought he was joking and told him to get the fuck up.

But Nader wasn’t moving, still in that Humpty-Dumpty position.

Nick Foles watched in the stasis of the night, where the humidity had now risen to 67 percent. He had played with Nader for six years, starting in junior high school. They were fellow co-captains. They perfectly complemented each other, Nader’s emotion a rabbit’s foot to Nick and Nick’s steadiness the same to Matt. Now he was watching his beloved teammate still not move.

Nader’s parents had their eyes trained on the game until somebody told them that Matt was down. They ran out of the bleachers, through 4,500 fans in silence as loud as any roar, except for the piercing scream of Nader’s girlfriend.

His father felt his pulse.

“Barb, Matt’s not breathing.”

Paul Nader did chest compression. Barbara did mouth-to-mouth. He didn’t revive.

Because this was Westlake, other doctors who were the fathers of players poured out of the stands. Allen Dornak and Greg Kronberg, both anesthesiologists. Cardiologist Paul Tucker, the father of future Baltimore Ravens placekicker Justin. They took over for Matt Nader’s parents. They checked for a pulse.

Still nothing.

Larry and Melissa Foles were there. They watched, like their son. A whisper shuddered through the sidelines that Matt Nader was dead.

By some miracle, Westlake carried an automated external defibrillator to games. There was no state requirement at the time to have it on the field; it had been given as a gift. It had never been used — another piece of equipment lugged around by the trainers. But it was charged and ready to go.

Tucker applied the pads of the defibrillator, with its rush of electricity.

Paul Nader watched. He could tell it hadn’t worked. He turned to his fellow physicians in a desperate last measure.

“Aren’t you going to create an air path for him?”

It didn’t happen.

There came a pulse.

He came to consciousness. An hour later at the hospital, there was nothing wrong with Nader. He was fully alert. It all seemed so freakish and unreal. Except that he would never play another down of football. He had gone through ventricular fibrillation, a condition in which the heart stops pumping blood. While there was no certainty it would happen again, the risk was too great. An implantable cardioverter defibrillator was inserted into Nader’s chest, to control irregular heartbeats.

Nick Foles knew the power of football dreams better than anyone, and how awful it must be to give them up when it isn’t your choice. He sat with Nader afterward at a hospital in Austin. They talked about what happened, to the extent that Nader wanted to talk about it, because Foles was (and is) never one to take anyone out of his comfort zone. Foles seemed almost philosophical, in his own way. “He just wanted to make sure I was okay,” says Nader today. “That I still recognized there’s more to life than football. Everybody has to stop playing it at some point.”

So maybe Nick Foles doesn’t have the edge of Peyton Manning. Or the come-from-behind fearlessness of Tom Brady. Or the gravitas of Drew Brees. Or the feet of Russell Wilson, or Colin Kaepernick, or …

He carries with him the fragility embedded into everything. The dividing line you never know. It’s something that no championship ring can ever teach him and few NFL players truly understand, clinging to their careers long after they’re over.

“He has remained true to his natural person,” Matt Nader says, “and that goes to show you how strong of a kid he is.”

But unless he stops being chickenshit and goes into the middle, he will never guide the Eagles to the place that only tantalizes us. We are tired, Nick. We are already dependent on you. So man up to be the man.

Sidle up to a bar on the road and order a slug of single malt, not a double shot of milk. It’s okay to address LeSean McCoy as “Shady” instead of “Sir Shady.” Don’t ever publicly say again that your favorite movie is The Lion King.

Acolytes get to heaven. Strut gets you to the Super Bowl.

Originally published in the July 2014 issue of Philadelphia magazine.