The Last Days of Bill Conlin

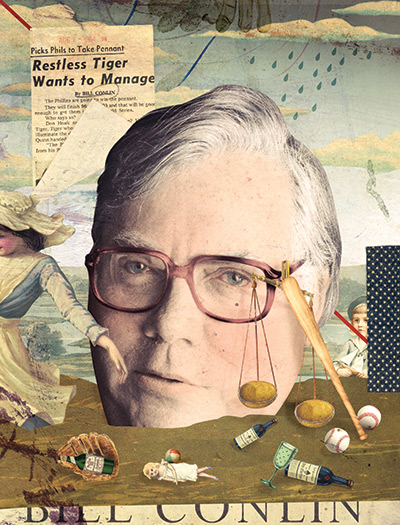

Illustration by Eduardo Recife

A year and a half ago, I flew down to Largo, Florida, and knocked on Bill Conlin’s door. It was early evening, and I couldn’t tell if he was home or not. Nobody came to the door. I thought I heard a TV, though. I knocked again.

Conlin had been the baseball beat writer for the Philadelphia Daily News for two decades, starting in 1966, then wrote a regular column for the DN for an even longer stretch, until the end of 2011. He was the city’s most-read sportswriter, and was nationally known via a long stint on ESPN’s The Sports Reporters as the fat guy waving his coffee cup in high-volume arguments that were often brilliant, or at least amusing. In the summer of 2011, he was inducted into the writers’ wing of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

But that December, the life he’d built for half a century collapsed, via a devastating article published in the Inquirer: A niece of Conlin’s and three other people (including one man) came forward to accuse him of sexually molesting them back in the 1970s, when they were children. They were speaking out after so many years, they said, because the recent allegations against Penn State football coach Jerry Sandusky had reignited their pain, and because it was time to end what amounted to a conspiracy of silence among Conlin’s family and friends covering up his horrible deeds. The alleged abuse happened far too long ago for charges to be brought. But the accusers were finally determined, they said, to tell their stories.

Conlin resigned from the Daily News immediately and wasn’t heard from again. Eventually, word got out that he was holed up in his condo in Largo. Where I stood, on an October evening at dusk, almost a year later. I knocked on his door a third time. I was sure I heard a TV.

Finally, I could hear someone coming.

“Yeah?” Conlin yelled — it was unmistakably his blistering foghorn voice — on the other side of the door. He didn’t open it.

I told him who I was, that I wanted to talk. Conlin and I knew each other a bit, having emailed occasionally as fellow journalists over the years. After the allegations hit, I’d emailed asking if he’d talk to me. He’d written back that he’d had a nervous breakdown and wasn’t ready to talk. He didn’t answer subsequent emails. I decided that getting face-to-face was the only chance I’d have. Though he still didn’t open his door.

Instead he yelled, “I’m not talking to anybody!”

So that was that — or so it seemed. I went back to my motel in Largo and called him. I got voicemail, and left a message: Would you have dinner with me? Just a dinner. A conversation.

I got an email back: You took a certain liberty coming down here without a prior head’s-up …

After venting a bit on the hell he’d been through, Conlin agreed in the email to have lunch the next day. But it would be, he said, on his terms.

THERE WAS A TIME when he was no mere sportswriter, but the most important journalist in Philadelphia. If that seems like a stretch, we’re forgetting the impact of the daily missives he would deliver from all over the country, all summer long, on our baseball team, in the halcyon days pre-Internet. As king of the sporting scribes here, Conlin shared with a few hundred thousand locals not only hardball derring-do, but his take on the world at large. Here is Conlin beginning a piece on the riots in Watts in August 1965, during a Phillies road trip to play the Dodgers:

This is a city at war with itself. The looters and the rioters are holed up, guerrilla-like, in a section of Los Angeles as big as Northeast Philadelphia. They have Molotov cocktails and whiskey and whiskey-courage enough to burn and pillage and rape and plunder. …

There are 13,000 National Guard troops here and the trucks whine through the freeway night bearing puzzled-looking kids from all over the state. Yesterday they were pumping gas and growing avocados. Today they are getting shot at. It is Vietnam in Southern California.

More often, Conlin’s style exhibited a sort of grand goofiness. One of his passions was weather. On a deadly summer day at the ballpark in South Philly in 1995:

Hot town, summer in the city. … The epicenter of the heat island this town becomes in central July is the molten turf of Veterans Stadium. Heat waves shimmer in the mid-afternoon sun like a scene from Lawrence of Arabia. … Yesterday was one of those brain-poachers where any inning I expected public address announcer Dan Baker to intone, “Now pitching for the Phillies … Omar Sharif.” I didn’t know if Ahmed Ben-Fregosi was trying to win a ball game or reach Damascus before Lord Kitchener.

A learned smart-ass. Vintage Conlin. He was pretty good at the particulars of baseball, too.

The Phillies generally sucked, but no matter: Baseball, in the slow unwinding of a season, offered Conlin the perfect writer’s playground. It was personal as well. He could drink and carouse with the best of them, like, well, a ballplayer; Conlin once told a friend that he put away a quart of vodka a day. And he was full of stories that couldn’t see print. On the road back in the ’70s, a certain Phillies slugger went drinking with his teammates. They met some girls and brought them back to their hotel, and somebody got the bright idea to fill the bathtub with ice water and bet the slugger that if he got in the tub, he wouldn’t be able to perform with said girls afterward.

Conlin also developed a reputation as a bar brawler on the road. A fellow sportswriter who covered Penn State football in the late ’70s says it was a habit on Friday nights at PSU: Conlin would regularly hit the bars, get drunk, then get pummeled. “It happened in bars in National League cities all over as well,” adds Bill Lyon, the longtime Inquirer sportswriter. “We used to kid him: ‘You’re 0-and-5, Bill.’ He did not fare well in fisticuffs.” The fights would be over … baseball? Women? “Probably both,” Lyon says.

Though there was apparently at least one drunken dustup Conlin won: He got into a fight with Phillies broadcaster Harry Kalas in a bar on a road trip in the ’70s — nobody remembers what it was about — and Kalas had to do his pre-game bit on TV the next day wearing sunglasses to hide a black eye and stitches. In another instance, it was rumored that Conlin made a pass at then-Phillies owner Ruly Carpenter’s brother’s wife on the team’s charter plane (in those days, sportswriters were invited on board), a move that got him permanently banned from the flights.

All of this makes him sound like a man-child perpetually living on the brink of disaster. The writer who used to accompany Conlin to cover Penn State football tells a story that suggests how he held things together.

Once a year, Joe and Sue Paterno would invite writers and their wives to dinner at their home on the Friday night before a game, and each year Bill dutifully brought his wife Irma and their three kids to State College. After the game one Saturday, Bill joined other writers filing their game stories in the stadium press box, which was strange: Conlin didn’t have a game story to file, because the Daily News had no Sunday edition. He could have departed with his family right after the game. But an hour passed. Two hours. Conlin was still sitting there, in the press box. Finally, as the others still pecked away, he left Beaver Stadium.

Maybe three hours later, the writer and some other scribes heading back to Philadelphia stopped at the Host Inn near Harrisburg for dinner, as they normally did. And there was Conlin, having dinner with his family. Conlin quickly called out to one of the writers, the AP’s Ralph Bernstein:

“Hey Ralph, is the party still going on?”

Party? Bernstein looked puzzled.

“The press party,” Conlin called across the restaurant. “Is the press party still going on?”

“Uh, yeah,” Bernstein nodded. It was obvious that Conlin had concocted a story for Irma as an alibi: that after all those football games he’d covered in Happy Valley, when he wouldn’t make it home until the wee hours of Sunday morning, maybe after yet another fight in yet another bar, he was late because he had to stay for the “press party.” That’s why he’d made his family wait in the car for him after this game: He had to make an appearance at the phantom press party.

At the restaurant that night, Bill Conlin, this colleague remembers, looked like a little boy who had been yelled at by Irma all the way from State College to Harrisburg, as if she had seen right through him. In fact, she was the one person who could throttle Billy, as she called him, the only one who could stop him in his tracks. She was tolerant, too, which amused friends — Irma seemed to treat her husband like a third, incorrigible son. As if she understood that Billy was sometimes going to be a very bad boy.

At the same time, there was a certain largeness to Conlin. He had been the lead guy in getting writers to settle in Florida, to rent condos instead of motel rooms, to even buy their own places. To bask. Long ago he started towing a Hobie Cat down from Jersey behind his station wagon every February, and there he’d be, trolling onto the beach off the Gulf as though spring training was his oyster. That’s how it went with Conlin. He might write about the players, but he drank with GM Paul Owens. He lived large. He was large. Everything revolved around him.

To understand Conlin, another longtime colleague of his says, you have to keep in mind what that early period of his life on the road — when writers could hang with

ballplayers — was like: a lot of drinking, a lot of women, but also a lot of late nights when there was nobody else. “I think he was a very insecure guy, and I think he was a lonely man,” the colleague says. Later in his career, “he would stay up and reply to people who wrote nasty emails. We always wondered why he did that. Nothing good could come of it.”

Only Irma, it seemed, could apply the brakes to some of Conlin’s worst impulses. But Irma, a longtime smoker, died in 2009 of cancer.

Two years later, the bottom fell out.

HE SAID IT, over and over: “I’m not Sandusky! I’m not Sandusky!”

Or rather, he screamed it, to A.J. Daulerio, the then-editor of Deadspin, a sports website heavy on gossip and snark. The two had had an email relationship for a few years. Conlin contacted Daulerio on the day in 2011 when he learned the Inquirer was about to run the story accusing him of the sexual molestations. Conlin thought he might be able to write a rebuttal for Deadspin. “He never said to me that the allegations weren’t true,” Daulerio says now. “His main defense was that he wasn’t Sandusky — yelling that over and over.”

As the story broke, the Daily News immediately accepted Conlin’s resignation. He never wrote anything for Deadspin.

Instead, he attempted to hole up in his Shipwatch condo down in Largo, where he’d been living full-time. But as with any big scandal, the national media descended — one reporter knocked on some 44 doors in Conlin’s complex, looking for dirt.

Conlin was scared. He retained Philly lawyer George Bochetto to represent him, to be the face of denial to the media; Bochetto would call Conlin to give him a sounding board. “The first couple of months,” Bochetto says, “he was extremely frightened about what might happen. He felt that everybody was stalking him.” Conlin swore to Bochetto that the allegations weren’t true, would go on and on about ruining the family name, the effect on his kids and their relatives’ memories of him. Bochetto urged Conlin to tell him war stories — the Civil War and generals of all eras were special Conlin obsessions. “To get him, at least for a moment,” Bochetto says, “to forget all the horrible allegations and that his life was ruined.”

Gene Neavin, a psychologist, had been friends with Conlin for three decades; they had met as next-door neighbors in Turners-

ville, Gloucester County. Neavin is a quiet man, a natural listener. He was a perfect friend for Conlin, happy to soak up the stories and the bombast. Neavin and his wife had followed the Conlins to Shipwatch, buying a condo themselves. After the brouhaha erupted, Neavin knew Conlin had to get the hell out of town. He worried that Conlin would kill himself.

At Neavin’s urging, Conlin slipped first to an old Jersey friend’s “safe house” in Bradenton for a couple days, then for a few months to the Dominican Republic, where he had once owned a house in Cabarete and where he still had some friends who didn’t seem to know anything about any allegations. Neavin joined him there for a bit. Conlin reverted to form: He drank eight or 10 rums a day and held court. “Stories, stories, stories,” Neavin says.

At first, Conlin needed to deny the charges; he would say over and over to his friend, “Gene, you’ve known me for a long time. Do I look like the kind of guy who would do that?”

Finally, bored, with a horrific cold, Conlin decided he’d had enough of life in exile: He returned to Florida. The media siege was done, but so was almost every friendship. Bochetto had stopped calling. So had Conlin’s old network of sportswriting cronies.

Conlin had known Hal Bodley since the two of them had covered the Phillies back in the ’60s; Bodley had gone on to national prominence as a columnist for USA Today. Just three days before the allegations of abuse broke, Conlin called Hal:

“Don’t you have time for an old man?” he growled.

“Sure,” Bodley told him, laughing to himself — same old irascible Conlin. “We’ll get together.” Bodley, too, lived a big chunk of the year in Florida, not far away. As was true of many people who knew Conlin, their friendship was complicated: There were a thousand good-natured arguments over baseball. And some not-so-good-natured moments — Bodley says he once confided to Conlin that he had talked at length to Phils pitcher Steve Carlton for a book he was writing on the team’s 1980 championship season, something Bodley wanted kept private, because it was a great coup — the famously taciturn Carlton didn’t talk to the press. But Conlin blabbed.

Still, Bodley respected Conlin: His recall of games, of moments in games, of a certain pitch in a particular game, was jaw-dropping. And Bill at the typewriter? It was a toss-up which was more outrageous: that he’d compare a Phillies comeback to, say, the landing at Normandy, or that he could actually pull it off.

But that was the last time they talked, the Sunday before the Inquirer article changed everything. Bodley never reached out to Conlin afterward. He never made a call to see how his old friend was doing. “I would have been cordial to him, if I’d run into him,” Bodley insists. But what could Bodley — or anyone, for that matter — possibly say to Bill Conlin?

Out of some 50 people who had gone to Cooperstown to honor Conlin’s induction into the Hall of Fame in July — including some surfers from his youth as a lifeguard — only one talked to him now: his son Pete. Conlin had been estranged from his daughter, Kim, for a quarter of a century; his other son, Bill Jr., had told his father that he had disgraced the family. “How do you live like that,” Hal Bodley wonders, “when everybody shuts you out?”

Conlin escaped into deep electronic geekdom. He bought a cable package that allowed him to watch baseball the world over. He studied weather online. He checked out Cuban soccer. He was a Breaking Bad and Dexter addict, and watched old Bogart movies. He emailed his old Daily News editor pictures of birds and Phillies slugger Ryan Howard’s new mega-house in Clearwater. He played Texas hold ’em online. And billiards. And golf — he told Gene he had better scores in cyberspace than Tiger Woods.

And he drank. A lot. A fifth of vodka would last a day, two max. Gene would come over, watch a game with him. Slowly, he got his friend to come out. Not to Conlin’s favorite Italian restaurant, Villa Gallace, a place he’d plug in his column every spring and where his picture had been on the wall, next to wrestler Bobby “the Brain” Heenan, something Conlin never failed to point out to visitors from Philly. He would even spend Thanksgiving there, he and Irma, with the owner, Luigi. But no more — after the allegations, Conlin was no longer welcome in Luigi’s restaurant.

Gene Neavin got him to come to the Pantry, a little place in their Shipwatch condo community. Not on Wednesdays or Fridays, when it was busy — crowds made Conlin feel like there was a target on his back. Sunday brunch was good, though. He could talk baseball there.

But the accusations always loomed. A couple times when Conlin was at the counter at the Pantry, talking, Larry Shenk came in. Shenk, now retired, was the longtime head of media relations for the Phillies; he knew Conlin well. Even inside, Conlin would be wearing his trademark big sunglasses, though Shenk assumes he spotted him there.

Shenk didn’t have any desire to go over and say hello, however. “I didn’t know what to say to Bill,” he says, “so I avoided him.”

BILL CONLIN’S TERMS for having lunch with me at Keegan’s, one of his regular spots, was to bring Gene along and talk to me strictly off the record — he wasn’t ready for his story to be told. Though it was clear he wanted to talk. The gruffness of the guy behind the door was gone. I asked him how he was doing.

“Terrible!”

He took off his yellowish goggles, to show me an eyelid folded back on itself. Now 78, he had a huge gut — he had to be north of 300 pounds — and swollen, scabby, peeling legs. He was battling skin cancer. He had diabetes. His face was covered in chaotic white fuzz. He had bushy white sideburns. He looked … terrible.

Conlin ordered seafood bisque and told stories. The Phillies in Montreal a long, long time ago: Our player gets beaned, so Steve Carlton hits Tim Foli in the ear, Montreal manager Gene Mauch charges the mound, nobody helps out Carlton, Mauch stomps him, and Lefty was never the same after that. Conlin kept talking, one tale unfolding into another. He told me that Penn State coach Joe Paterno started losing it mentally at 70. He told me how close he was to deceased Phillies broadcaster Richie Ashburn — “Like this,” Conlin said, as tight as his two fingers. He talked about Pete Rose and a certain nationally known sportswriter renting a place together and how Rose would supply “the meat,” meaning cheerleaders, and how one of the cheerleaders was the wife of a well-known Philadelphia sports icon. He told me he had washed out of Bucknell more than half a century ago because he got drunk one night, drove his car into seven parked cars along the main drag, then ran away.

Stories. Conlin was full of stories. He was regaling me.

He told me that years ago he’d begun to pen a novel, but he’d never finished it. That he didn’t miss writing his column for the Daily News — maybe he was “written out.” He said that cigarettes had killed Irma, and that cleaning out his house in New Jersey was horrible. He said he was thinking of starting a blog or website on his various interests.

At one point, his tenor changed. He was ready now. He had a manila folder with him, and opened it. Inside were pictures of some of his accusers.

“I panicked,” Conlin said. “I shouldn’t have resigned from the Daily News — they didn’t have anything. It would have gone through arbitration.”

Conlin showed me a photo of his niece at his house at some holiday celebration. In the picture, she was older, he said, than the age when she claimed to have been abused. And here she was, at his home.

“It looks like she’s having a good time,” Conlin pointed out. This made it obvious, he said, that he hadn’t abused her.

Then he put the pictures away and went back to his stories.

Not long afterward, when I was shaking hands with Bill and Gene in the parking lot of Keegan’s, I got the somewhat eerie feeling they actually believed that what Conlin had said about his niece at his house, about her presence there after he’d allegedly abused her, proved something. Later, Gene would tell me that in all the years he knew Bill Conlin, he never saw any abuse. And that Conlin never admitted to any of the allegations.

It was as if they were living in a private echo chamber for two.

KELLEY BLANCHET, Bill Conlin’s niece who alleges he inserted his finger in her vagina when she was seven years old, and three others claiming that he sexually abused them when they were children, wrote about what happened to them in a recent New York Daily News article. They say that Conlin found his victims around the beaches of Margate, where his nickname was “Slick Willie,” and in the Whitman Square neighborhood where he lived.

Conlin’s accusers say that many adults knew he was a pedophile, but for almost half a century, no one went to police. The reason why, they say, is clear: “Conlin was a sadistic and vengeful man. He was a master at using his large stature, his prestige, his access to sports stars and sporting events and his wealth to prevent victims (and his victims’ families) from reporting his crimes.”

In going first to police in 2010, and then to the Inquirer the next year when it was clear too much time had passed for the legal system to pursue Conlin, the accusers say they “didn’t want money. We wanted him exposed for what he was. We wanted his facade of fame and fortune to crumble in the face of what he had done.”

After my lunch with him, Bill Conlin would live another year, most of it consumed with medical problems. The worst was COPD, a lung disease. Conlin’s medical care was as chaotic as the rest of his life. He lost his supplemental medical insurance because he never received the bill from New Jersey to renew it, Neavin says. He was stubborn about going to doctors — he had no regular physician in Florida. He ordered medication online from India. In the spring of last year, he fought Gene and a caregiver about going to the hospital for prostate trouble, but finally relented.

The last few months of Bill’s life, Gene would have to move his friend’s BMW or Lexis convertible close to the condo door. Bill would shuffle out slowly, eventually slide behind the wheel — Bill always drove, and drove fast; he hated slow Florida drivers. Then he would shuffle into Keegan’s. He was okay once he sat down. He could talk and eat just fine. In the end, he’d quit drinking. In their conversations, any talk of the allegations had long since faded away.

Early this winter, when his breathing got really bad, Conlin didn’t fight Neavin and his caregiver on going to the hospital. He was in bad shape.

In the hospital, gasping for breath, he said to Neavin, “I’m finished.”

Neavin didn’t believe him.

“I’m finished, Gene,” he repeated.

Five minutes later, Bill Conlin was dead.

“It’s terrible,” Neavin says, “watching somebody die.”

Conlin’s sons Pete and Bill flew south to have his body cremated.

It was their first trip to Florida since the allegations.

Originally published in the April 2014 issue of Philadelphia magazine.