What Would Philly Look Like If Urbanists Ran the City?

What would happen if we let Philadelphia urbanists run the city? Illustration by Sean Rynkewicz

In the middle of a major crisis, it’s not exactly easy to think big. Not when our paychecks — and city coffers — are made so small. But struggle and imagination aren’t always antithetical; after all, the bubonic plague gave way to the Renaissance. Catastrophes illuminate our shortcomings and reveal holes in the safety nets we assume we can cling to in moments of desperation. In the grind of “normal” daily life, we rarely allow ourselves to pause and reconceptualize the way a city should run. Instead of pinpointing the root causes of issues, we brandish Band-Aids and plow ahead. But there’s real value in stepping back and reenvisioning the system that is our city — and pretending, if just for a moment, that there isn’t an endless list of obstacles (starting with money) standing in the way of greatness. If we can never dream, we can never do. This list of gutsy, enterprising ideas for Philadelphia comes from some of the city’s most steadfast visionaries: urbanists. They’ve got sketchbooks full of plans, and they’re ready for a renaissance.

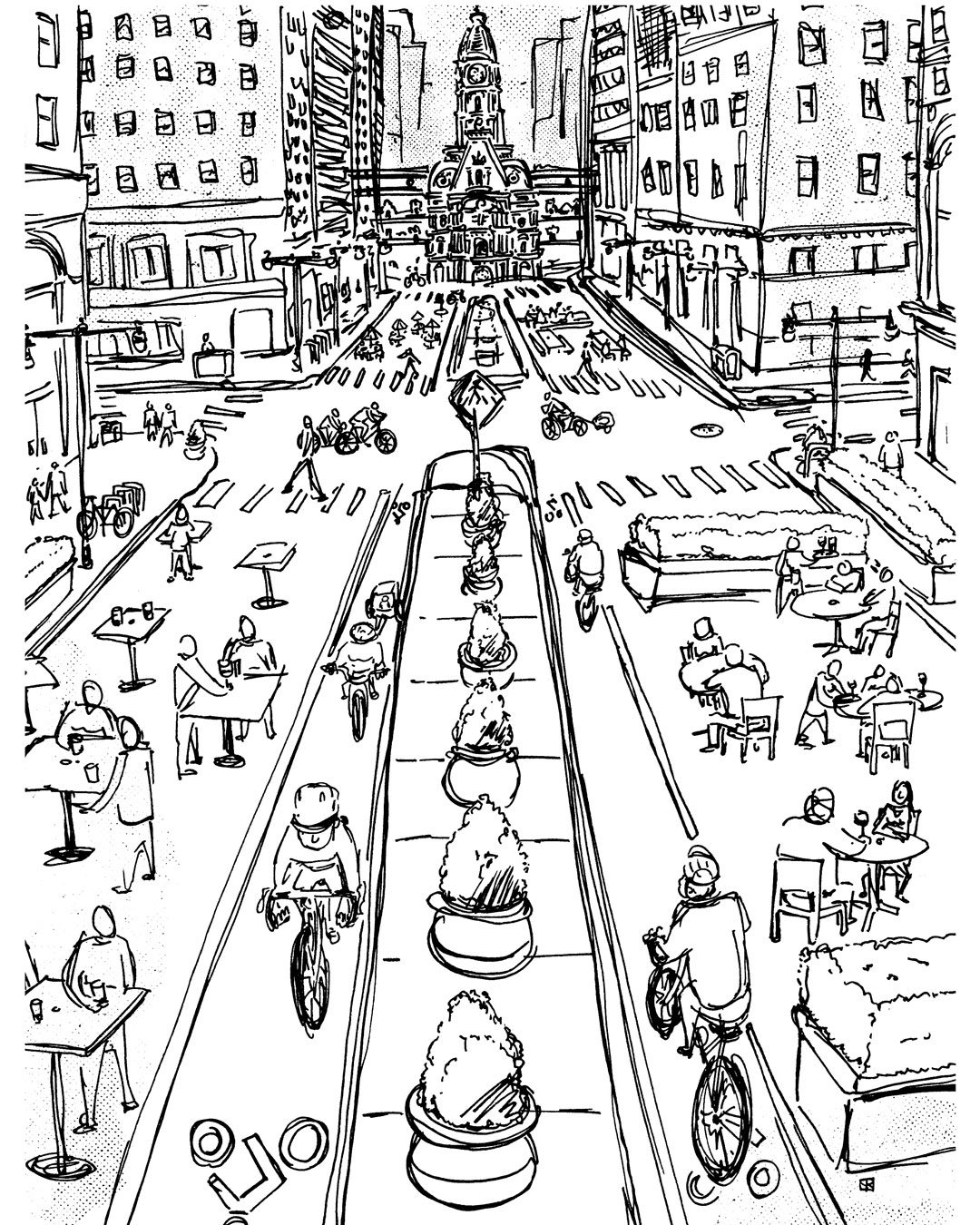

Make Center City a pedestrian utopia.

Where to start? How about banning cars from the stress-inducing City Hall traffic circle (which just might be Dante’s ninth circle of Hell)? “Even though Dilworth Park provides an excellent plaza, the streets around it are an incredible barrier to access and lessen its quality,” says Drexel prof Katrina Johnston-Zimmerman, owner of city planning consulting firm Think.urban. Lawyer and former City Council candidate Lauren Vidas suggests turning Center City’s quaint streets into pedestrianized “superblocks” where people can play, mingle, walk and just … exist.

Illustration by Sean Rynkewicz

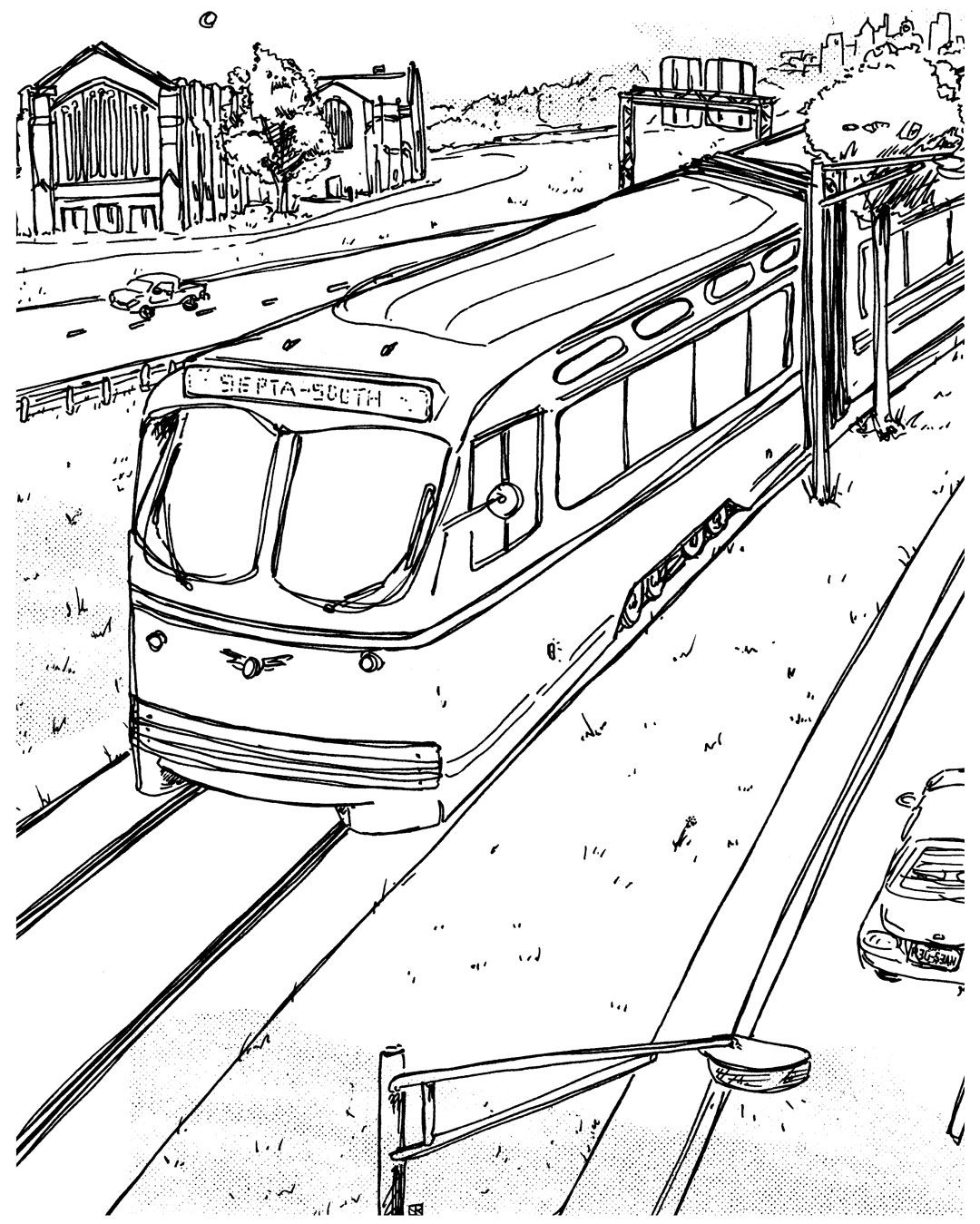

Put a train on Roosevelt Boulevard, already.

Nearly half of our city’s deadliest roads cut through low-income neighborhoods that are primarily Black and brown, according to a 2018 study by the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia. The deadliest of all? North and Northeast Philadelphia’s Roosevelt Boulevard. Urbanists have long proposed life-saving solutions there, including building a high-speed transit line. Housing and community development specialist David Feldman says we should act now. His big idea: Build a shallow-trench light rail along the Boulevard’s median from Broad Street to Red Lion Road, with a spur to the Frankford Transportation Center. Light rail, Feldman says, sends a stronger signal than the road’s current bus rapid transit line: “There’s something about transit on a rail — people can trust that long-term, it’s going to be there.” Plus, the line would connect many more Philadelphians to the good-quality, lower-cost housing and vibrant businesses (including the rich international cuisine) of the Northeast.

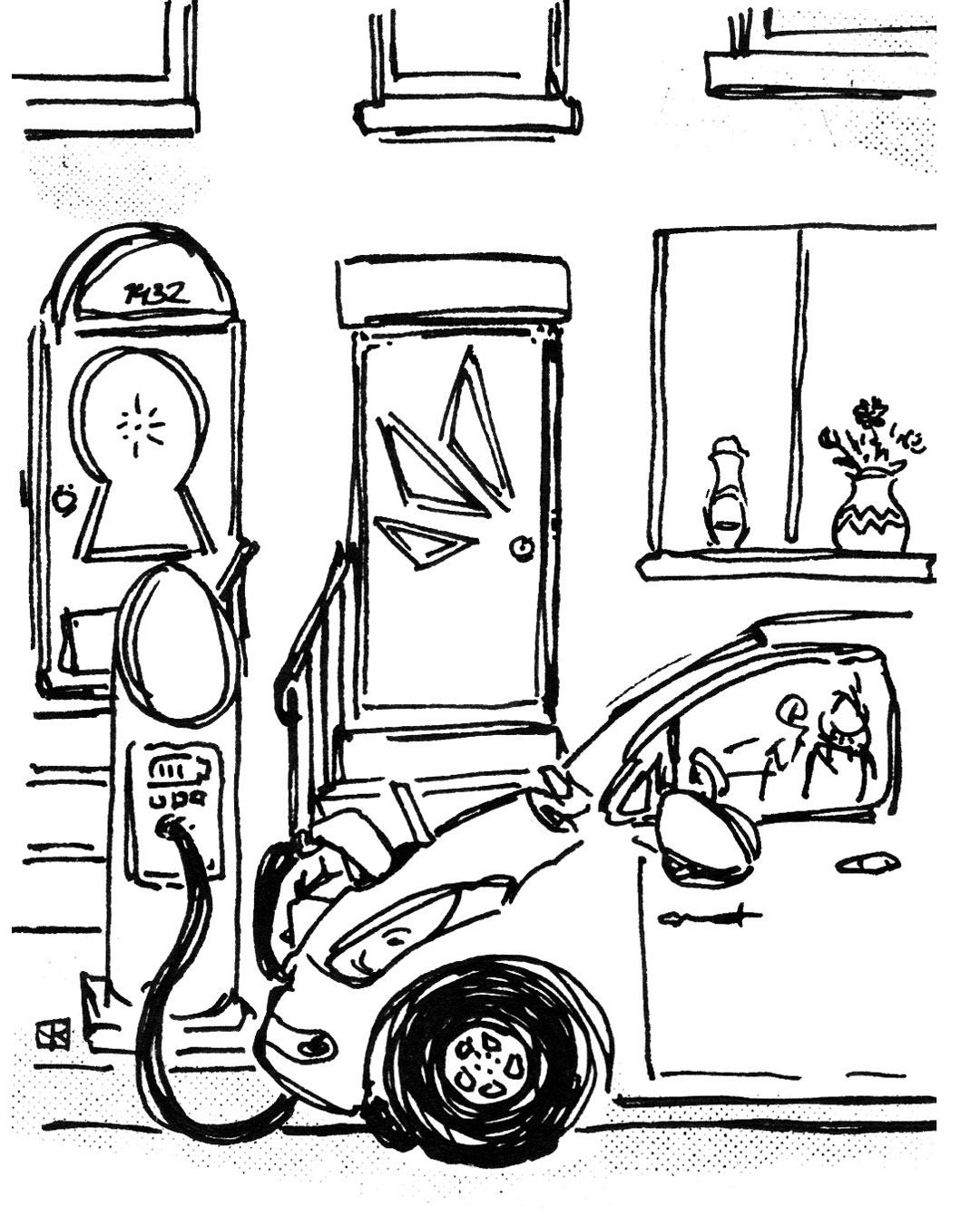

Illustration by Sean Rynkewicz

Require all new billboards to be hand-painted.

Billboards are hideous eyesores that contribute to the persistent sensation that someone is trying to sell you something ALL. THE. DAMN. TIME. Jennifer Kates, chief of staff for City Councilmember Helen Gym, suggests alleviating corporate exhaustion via public art: By paying artists to hand-paint advertisements, we’d require businesses to become more civically engaged, create jobs, and beautify our city.

Employ a women-run urban design collective to rethink our city’s systems.

For too long, white men have held the keys to our city. As a result, Katrina Johnston-Zimmerman argues, the patriarchy is manifested in our built environment — and reflected in features like phallic skyscrapers and menacing roadways, products of a society that prioritizes competition and defaults to market forces. How to reverse that? Employ an intersectional group of women to rethink our systems so the city looks and operates differently. The goal would be to prioritize what Johnston-Zimmerman calls a communal “heart-centered cities” approach that features “compassion over competition, care instead of capitalism.” She envisions plentiful public space and multimodal and car-free roadways that increase accessibility to caretaking entities like hospitals, day cares and schools. Imagine protected bike lanes on roads like Spruce Street and Broad Street, so hospital workers can safely travel between Center City and hospitals in University City and North Philadelphia, and snow plans that include plowing residential roads and school and hospital zones first. We could learn from Tokyo, which reserves train cars for disabled people and caretakers with children, and Rwanda, which has established a permanent women-led mini-market with space for breastfeeding.

Illustration by Sean Rynkewicz

Make public art actually public.

Why spend a fortune on one-off art installations that risk becoming outdated? (Cough, the Rizzo and Columbus statues, cough.) Urban designer and Penn post-doc fellow Matthew Miller suggests that Mural Arts create an “Urban StoryCorps” of sorts that would install and program interactive media in neighborhoods — think Eastern State Penitentiary’s “Hidden Lives Illuminated,” or Michelle Angela Ortiz’s recent Rizzo-mural-replacing projection honoring multicultural communities in the Italian Market — to ensure that demographic diversity doesn’t outpace monuments and that neighborhoods have a say in how they’re represented.

Seize the sidewalks, then plant a million trees on them.

Laws regarding who’s responsible for sidewalk maintenance (property owners, not the city) are way too confusing and discourage any upkeep at all. The city has jurisdiction over sidewalk trees, so it should exercise eminent domain over sidewalks, too. While we’re at it, let’s kill two birds with one stone: Environmentalist Meenal Raval says we should hire a fleet of city workers (from the neighborhoods where tree-planting is being prioritized) to manually sweep streets while planting trees and fixing up sidewalks.

End single-family-only zoning in Center City.

Single-family zoning contributes to rising housing prices, racial segregation, increased carbon output, and education inequities, says urban political specialist Diana Lind, author of the book Brave New Home. She suggests changing our zoning code to ban new single-family buildings in Center City and allow for denser housing especially near major transit thoroughfares (like along the Market-Frankford line in Fishtown and neighborhoods north of there). To ensure future equity, we should prioritize affordable housing close to transit connections. “The more people we can get living along our transit lines, the more people have quick access to jobs, Center City and other hubs,” Lind says.

Make Regional Rail more like the subway.

The Main Line wouldn’t exist without the train line. Let’s make the railroad even better by increasing frequency and decreasing fare prices, so it functions more like rapid transit — an idea SEPTA has tantalized us with in the past. Commuting would become more flexible, and day-trip getaways into the surrounding counties would become that much easier. A bonus? Ridership would surely jump.

Illustration by Sean Rynkewicz

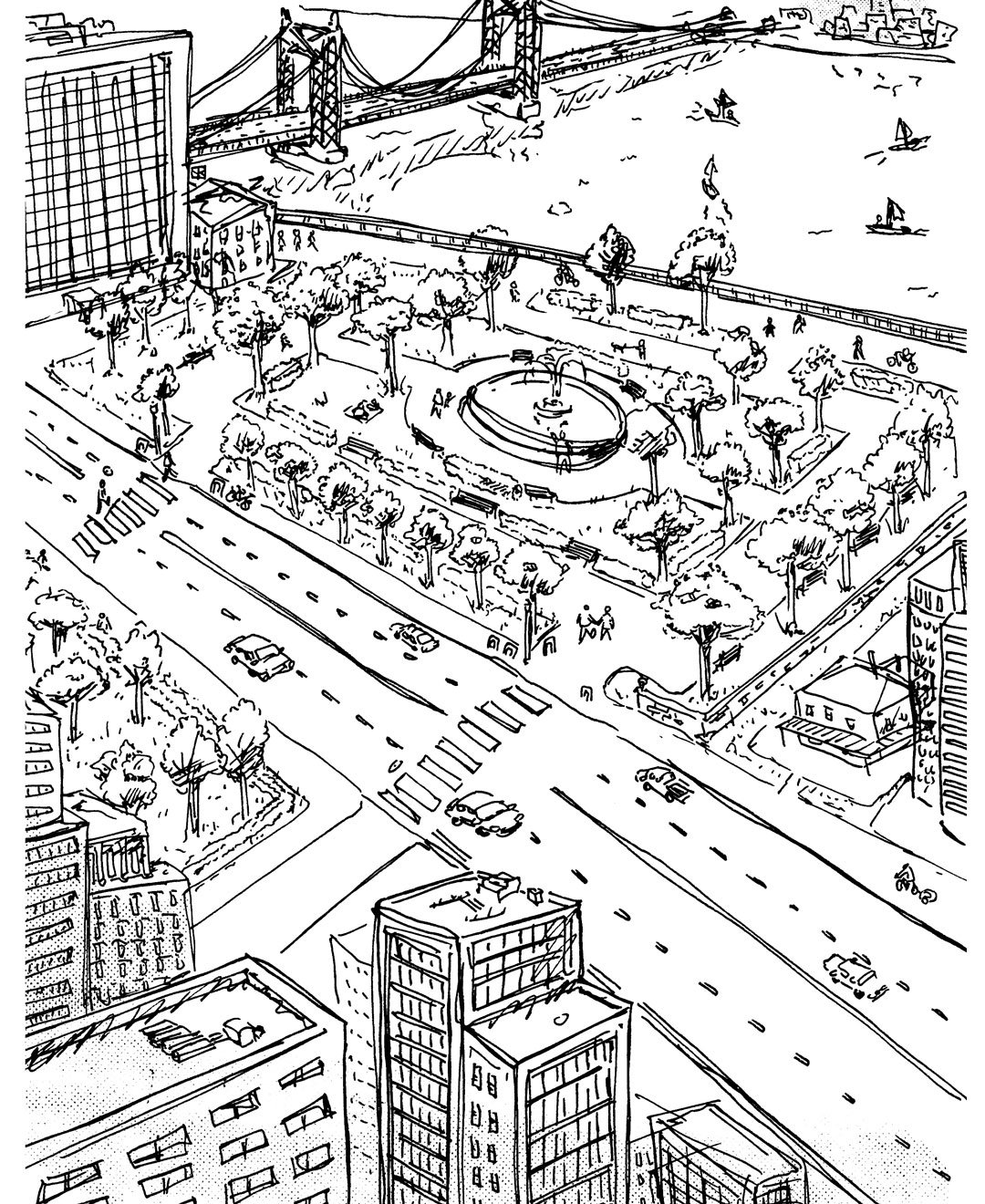

Sink Center City’s fugly expressways.

Instead of continuing to spend a fortune repairing eyesore interstates 95 and 676, let’s reimagine them for future transit demands. Specifically, take inspiration from the Delaware River Waterfront Corporation’s plan to build a park over a portion of I-95, and bury and cap all of these urbanism impediments. Then build green space and smaller streets atop to improve walkability, spur development, and really amp up waterfront access. “Let’s not give the next generation the gift of giant highways that are deadly for urbanism and any type of human interaction,” says Harris Steinberg, of Drexel’s Lindy Institute for Urban Innovation. This would be a costly, high-stakes engineering project, but it’s been done before: Rochester, New York’s Inner Loop East Transformation Project allowed for multiple new mixed-use developments and below-market-rate apartments up top.

Illustration by Sean Rynkewicz

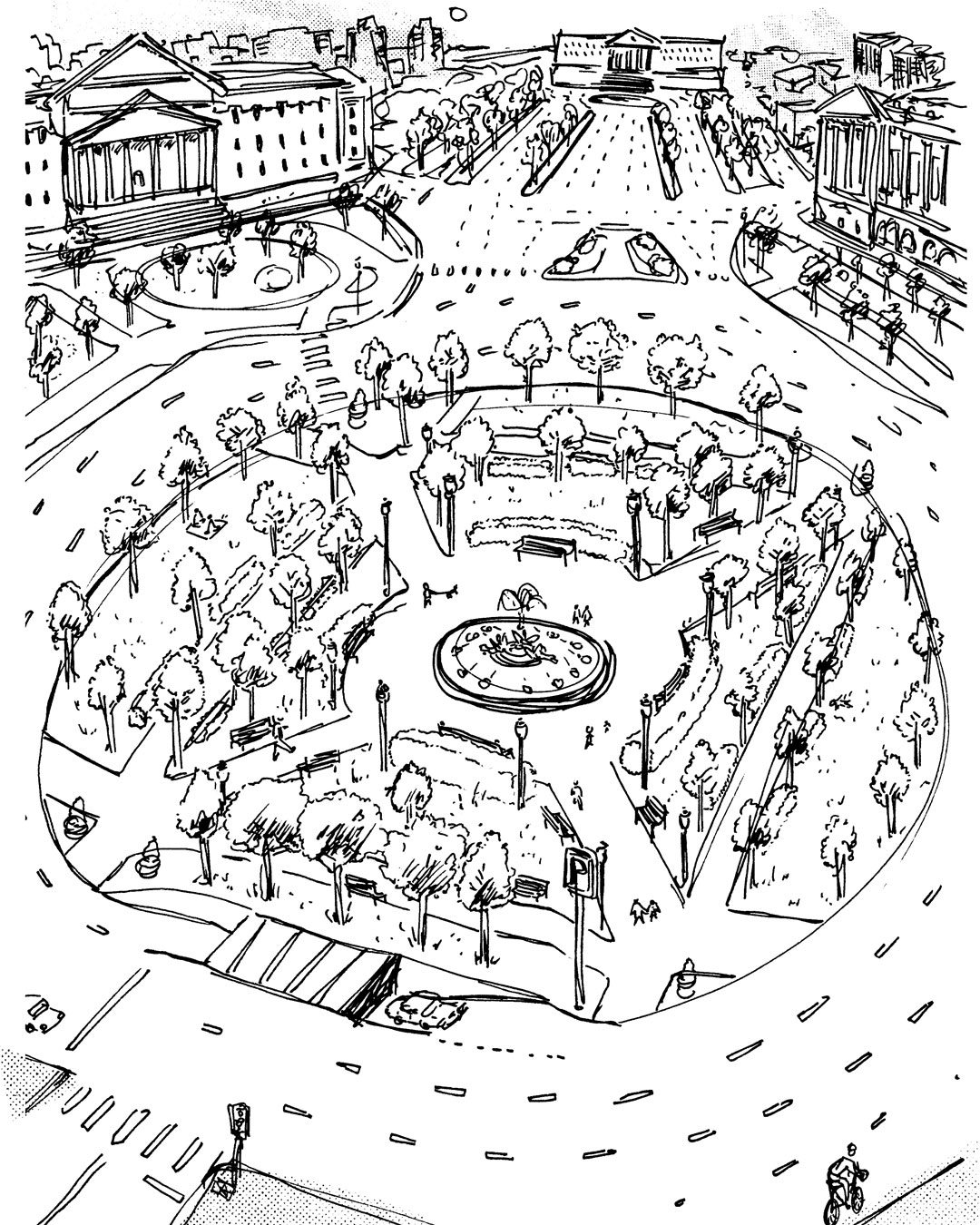

Make Logan Circle a square again.

Logan Circle is the only one of William Penn’s original squares that hasn’t been wholly transformed into a public space — and the time to rectify that is now, Diana Lind says. To help alleviate the parking crisis in Center City, let’s engage one or two of the many booming businesses in the area (hello, Comcast) to fund the creation of a massive parking garage beneath the square; commuters could ditch their cars and walk to offices, restaurants, retail and more. “Call it David Cohen Park and be done with it!” jokes Lind.

Illustration by Sean Rynkewicz

Put electric vehicle parking everywhere and anywhere.

Yes, we know the parking wars are real. But climate change is more real. We need to make it easier for people to choose more sustainable modes of transportation — whether by granting them spots outside their homes or creating vertical EV charging lots to save space. Let’s start with one EV charging spot per block. “The goal is to grow infrastructure to facilitate electric vehicles,” says Philadelphia 3.0 executive director Alison Perelman, “and get as many combustion vehicles off the road as we can.”

Gamify zoning reform.

Planning and zoning are vitally important. But don’t get Penn’s Matthew Miller going on how boring they are — at least, as currently practiced. Miller says Planning Commission and Zoning Board of Adjustment meetings feel like “forensic focus groups, tokenist therapy sessions, or sideshows for the charismatic naysayers … cloistered and jargon-filled and inhospitable to casual observers and everyday people.” He suggests turning to gamification to transform these processes into democratized, free and productive online workshops that will engage the everyday people who have to live with the decisions. The developers of SimCity (the game where you build and run a pretend city) have done gameplay sneak previews with MIT urban planning students, so the utility of such a game as a planning tool seems obvious. So much so that Drexel University game designers, with support from the Knight Foundation’s Open Data initiative, are now at work on an urban planning game called SIM-PHL that lets players reimagine the Mantua neighborhood in West Philly.

Published as “What If Urbanists Ran the City?” in the September 2020 issue of Philadelphia magazine.