50 Years of Fresh Air: An Oral History

In September 1975, Terry Gross, just 24, sat down in the host chair and turned Fresh Air into a genre-defining radio show. Fifty years later, Gross, her colleagues, and her competitors look back on how one show became a cultural touchstone.

Fresh Air’s Terry Gross in the early ’90s / Photograph courtesy of WHYY

In college she wanted to be a writer, but the words refused to sparkle like her heroes’.

Teaching was a disaster. The middle-school kids mocked her purple corduroys. She lasted six weeks.

Volunteering at the college radio station in Buffalo, WBFO, though … now, that was magic for 22-year-old Terry Gross. She just turned a knob and her voice was out there. With interviewing, the revelation was more practical. The story was in the person; she simply had to bring it out.

She never quite gave up her literary inclinations. Every interview Gross does on Fresh Air — and she’s done well north of 13,000 — is broken down into chapters, with room to weave in human meanderings: a scar on a forehead, that New York accent, the brother who didn’t make it. Close your eyes and you can hear that voice — a heaping teaspoon of friendly, a level cup of authoritative. All together you get what Fresh Air co-host Tonya Mosley calls a “slowdown, an intimate moment.”

Gross began hosting Fresh Air 50 years ago. The show belongs beyond Philadelphia, even though it’s produced and owned by WHYY. It is carried on 651 NPR stations nationwide and is heard by 3.7 million listeners every week; another 1.6 million download the show.

Here’s how Terry Gross turned a passion into a cultural force.

I. “I had no other way to be.”

The story of Fresh Air begins in early 1970, when Bill Siemering, the general manager at WBFO and the person who went on to write National Public Radio’s original mission statement, sought to chronicle student protests at SUNY Buffalo.

Bill Siemering, station manager, vice president for radio, WHYY, 1978 to 1987: In the afternoon, I had a program, This Is Radio, as in “This is radio, damn it. Pay attention.” We would talk about the arts. We would talk with writers — a lot of writers would come through — and other artists. Then we’d have inserts from reporters. It was very informal, but, also, we would try to make it as interesting as possible. It was a miniature All Things Considered in a way, in that we were regarding the arts and culture as important parts of understanding the news.

Terry Gross, host and co-executive producer, Fresh Air: NPR stations, a lot of them are based on college campuses. And college campuses were where the heart of the women’s movement was in the ’70s in the early days of NPR. Women got a foothold there. And with the help of Bill Siemering, women got a major foothold — especially with Susan Stamberg, Nina Totenberg, Cokie Roberts in the early days. Those are three of the lead reporters. It was very free-form, very creative, very patchwork, room for all kinds of shows.

And because it was based on college campuses, you didn’t have the standard voice-of-God male classical music voice, nor did you have the [adjusts voice] sexy, female late-night voice or the progressive hipster DJ.

Bill Siemering: When I was hiring people at NPR [Siemering started in November 1970], the other executives who came from television, one of the histories said they had “disdain” for me when they saw who I was hiring, because some of them didn’t have extensive experience. I was looking for other qualities.

Terry Gross: People could come in as they are and just talk and be their best public self. I had no other way to be. I don’t think commercial stations would have ever dreamed of hiring me.

Jay Kernis, various roles, NPR, 1974 to 1987; senior vice president for programming, 2001 to 2008: She was authentic. You never felt she was playing a correspondent or playing an interviewer. You always felt, This is a real person, and I can trust you.

II. “A blank slate for me to fill.”

Terry Gross edits tape in the mid-’70s / Photograph courtesy of WHYY

By 1975, Gross, then 24, was on WBFO co-hosting this is radio, then a three-hour daily radio program. The show had spread beyond Buffalo. David Karpoff, the former program director at WBFO, had started a new version at Philadelphia’s WUHY (later WHYY) a couple of years before. It was called Fresh Air. And host Judy Blank had left after just a few months in the host chair.

Terry Gross: Jim [Campbell], the station manager, who was a good friend of mine in Buffalo, said, “You should apply for this. I’ll help you.” He helped me write a résumé. He probably convinced David to hire me. [Laughs] When I got the job, I thought, I don’t know that I want to leave Buffalo. I’ve got friends here. I love the radio station. It was a very creative radio station. I had one person I knew in Philly — well, two people.

I had to think it over. Finally, I decided, Well, take it. It’s actually a paid job — unlike what I was doing in Buffalo. [Laughs]

Fred Landerl, coordinator of operations, WUHY-FM, 1976; program director, WUHY-FM/WHYY-FM, 1977 to 1984: WUHY was a nonprofit radio station (as it still is today), then operating with a shoestring budget, that was significantly made up of one-hour and half-hour specialty programs produced by volunteers.

Terry Gross: I thought of it as a blank slate for me to fill. It’s not like it had a huge listenership where somebody had been there a really long time.

Lawrence Lichty, former director of audience research and evaluation, NPR, 1980 to 1981: Most stations that were CPB [Corporation for Public Broadcasting] stations were either classical music or they were called “variety,” which means anybody shows up.

Terry Gross: Other people on the staff could sign out an hour and do an interview on the show. I thought, That’s not the way I’m going to do it. The music in between was I think picked by the classical music program director. And I wasn’t going to do that either. I knew very little about classical music, and I knew I wouldn’t even be able to pronounce most of the names of the composers. [Laughs] So I thought, I’m going to play the music that I used to play in Buffalo. So it would be a mix of jazz, folk, rock, punk, blues, rhythm and blues, soul. Once, while I played the Ramones, I was getting these calls — “What are you doing to my radio station?” People were really upset.

The program director who hired me knew what he was getting, and he was not objecting. The station manager at the time, if he was paying attention, never said anything. The higher-level management — I don’t think they were listening.

Fred Landerl: For the first few years, Terry was the entire staff of Fresh Air, producing three hours of live radio every weekday afternoon. She booked the guests, met them at the door, interviewed them live on the air, and then after the interview she called a cab for them.

Terry Gross: It was a very lonely job at first.

Dave Davies, former politics reporter, WHYY; longtime fill-in host, Fresh Air: There was one week, she had to do two interviews five days in a row. I remember saying to her, “Terry, can you imagine that you used to do two to three interviews every day, every week?” And she looked at me and said, “I don’t know how I did it.”

Terry Gross: The offices were so horrible back then. We were at 46th Street and Market in the studio where Dick Clark used to do American Bandstand. Everything was just so old. The upstairs toilet always used to leak, and it would leak onto my desk. One day it leaked into my coffee.

Fred Landerl: There was no decor in the inexpensively divided-up, hand-me-down space that radio occupied. Or TV for that matter. It was T-shirt hot in the winter and freezing cold in the summer — radio was located across the hall from the TV studios, which had to be kept cool so that when the studio lights were turned on for the cameras, people didn’t wilt from heat exhaustion.

Terry Gross: There were times when I looked for another job. Maybe it was just one, a local TV interview show. I think I was applying to be a producer, but even if I was offered it, I don’t think I would’ve taken it. They were saying things to me like, “Say we have on a novelist, we’re not gonna talk about his novel. We’ll try to figure out, did he just get married? Did he just get divorced? We’ll do a show around that.”

And I thought, Yeah, I think I’d want to talk to them about the book, too.

III. “It started being fun.”

Danny Miller was studying film and music therapy at Temple University when he joined Fresh Air in 1978. The same year, Bill Siemering, the man behind Fresh Air and the creator of all things considered, arrived in Philadelphia.

Terry Gross: Danny came on as an intern and kind of saved me. [Laughs]

Danny Miller, co-executive producer, Fresh Air: I just wrote her a letter saying, “I’m looking for an internship and I live nearby, and I have a lot of records you might want to use on the station. I’m a big fan of Lenny Bruce, and blah, blah, blah.” I made an appointment for an interview. Probably because I was really nervous, I asked Terry — and, by the way, this was in the station — if I could bum a cigarette. Rather than being this kind of amateurish thing, I think Terry saw a real person nervous enough to want to bum a cigarette.

Terry Gross: I was always trying to stop smoking and bumming cigarettes from whoever I could (as if it didn’t count if you weren’t buying them yourself), so I totally identified with Danny asking me for one, even though I don’t think he was trying to quit at the time.

Danny Miller: I’m pretty sure it was a Winston.

Terry Gross: It started being fun, because there was somebody to work with. And we were very much on the same wavelength. And he lived right around the corner from the station. On snow days, there weren’t going to be any guests because no one could get anywhere, so he’d go around the corner and get some records. We’d play Lenny Bruce records and figure out ways of filling time.

Danny Miller: As a very young person, I realized that Terry was kind of special. I could tell this is something that is kind of extraordinary and it’s getting better and better and better.

Mark Vogelzang, program director, station manager, WHYY-FM, 1984 to 1993: Danny understood deeply the ethos and the intellectual capacity that Terry had [and] was bringing to the show every day.

Roberta Shorrock, director, Fresh Air: He has this work ethic that’s just crazy. I think that he can deal. He stays calm in a million different crises and deals with so many different things and just stays steady. So those two were the best match. They were made for each other.

Terry Gross: I think we really have enjoyed and felt fulfilled by doing the show and making it grow. We like working with each other. It was just kind of amazing to see the show grow and change — little by little and then a lot. [Laughs]

Danny Miller: Terry changed my life. I totally owe my career and everything that’s good about it to Terry. I thought I was going to be an industrial documentary filmmaker doing promotional stuff for companies. That really wasn’t of interest to me. So to enter a world that I was excited about — movies, jazz, books, the news — and have hands in creating something that would be in people’s lives because it was on the radio — that was the opportunity I had with Terry.

Terry Gross: ’78 is when Bill Siemering came, and that changed everything too. You’ve got Danny and you’ve got Bill Siemering. It’s like, why would I leave?

Mark Vogelzang: He didn’t like bureaucracy, the structure of bosses and everything else. But he was always in the world of ideas.

Danny Miller: He just gave you confidence to try things. He respected your judgment. One of his mantras was I manage people like I would like to be managed myself: to be there, to be supportive, to trust them.

Terry Gross: He was so encouraging of everybody’s creativity. He looked out for us, including in conflicts with management. He wanted to protect us and to protect our creativity, our editorial freedom, and to do his best to get us livable salaries.

He really worked hard to keep Danny. When he graduated Temple, Bill found ways of bringing him on part time and then bringing him on full time and then giving him raises — and it was hard to do at the station. Radio was part of the TV-radio station. And radio was considered, at the time, lesser than television, so it was hard to free up any money. Bill was great at that too. And he knew people at NPR, so he knew what was going on through the network.

IV. “I think you’re ready to become a national show.”

Terry Gross, Danny Miller, and Amy Salit in 1989. / Photograph courtesy of Mark Vogelzang

Mercifully, Fresh Air became a two-hour show in January 1983. “Sometimes it would feel like we were dragging people out of the street to be on the show,” Miller says. Gross no longer had to interview the proprietor of a celebrity look-alike business. “Terry still had standards even when we had to fill this calendar up,” Miller quips. In 1985, a best-of edition debuted on NPR stations. More changes were in store.

Bill Siemering: My office was off the hallway, so as guests were leaving, I thanked them. They’d say, frequently, “That was the best interview I’ve ever had.” That’s when I felt it’d be good if we could syndicate it for a larger audience.

Danny Miller: Bill gave us the confidence that this could actually be a national show.

Amy Salit, various roles, WXPN, 1979 to 1985; associate producer, producer, Fresh Air, 1985 to 2024: Even back then, Terry was considered to be the best in the business. For publicists, especially in publishing, that was the booking to get in Philadelphia, even in the early 1980s, the 1970s. She was a huge deal even for publicists in New York and L.A.

Ken Tucker, pop music critic, Fresh Air: What Terry was doing was really unprecedented — not just on NPR, but on radio. She would ask people questions that sometimes seemed very personal or sometimes had an implicit judgment. If she was talking to someone like John Updike, I would get a feeling about which ones of John Updike’s books she admired and which ones she didn’t. There was a critical sensibility working behind so much of what she did when she talked to people in the arts. She was not afraid to either overtly or implicitly talk to an artist about what was strong and what was weak about their work.

I found that as a critic it really struck me what an extraordinary thing [that was] and how seldom I heard it anywhere else: how you could go deep in a conversation and break down the interviewer’s reticence and get to something honest and true.

Danny Miller: Stations would keep asking me, “Can you send me this? Can you send me that for the weekend?” So, I figured, let’s just do a weekend show that would be the best of the week. I mean, it was not a brilliant idea.

Mark Vogelzang: And then we wrote a bigger grant to CPB for new programming.

Terry Gross: The way I remember it, [Bill] came to us and said, “I think you’re ready to become a national show.” He talked to the heads of programming at NPR. He wrote the grant that got us a large Corporation for Public Broadcasting grant. We had to rebuild everything. We had to pay for fiber-optic lines to connect us to Washington NPR headquarters and to the NPR bureau in New York, because we wanted to have really good sound.

Lawrence Lichty: In the case of Terry Gross — one, she was good. Two, she was lucky on satellite. Because she was good, the other stations would then carry her. She’s nothing without carrying Boston, Chicago, etc.

Robert Siegel, director of NPR’s news and information department, 1983 to 1987; former co-host, All Things Considered, 1987 to 2018: One thing you should never forget: From ’67 until the late 1990s, the technological landscape tilted NPR’s way.

Amy Salit: We could get guests from all over the world. When she was doing it live, the guests had to be in Philly. She didn’t want to do phone interviews. With satellite connections and digital connections, she could interview guests who were not in Philly and it sounded like studio quality.

Terry Gross: What I always tell people who think it’s weird that the interviews are long-distance and there’s no video component: It’s like talking on the phone. We all do it.

Robert Siegel: NPR was very much connected to FM radio. When the FCC allocated frequencies, they took the least valuable part of the spectrum, the bottom of the FM dial, and limited those stations for noncommercial, educational purposes. No one was listening to them. The huge change in American radio habits came in June of ’67 when Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band comes out. The interesting sounds are murdered by highly compressed AM radio signals; you want to hear them in stereo. It’s the most popular, most desired album in the world.

I think that began the stampede from AM radio to FM radio. Terry comes along, as with the NPR news programs, [and] she’s catching a wave.

Roberta Shorrock (left) and Audrey Bentham in the control room in 1999. / Photograph courtesy of WHYY

Mark Vogelzang: This was part of a trend that a bunch of us who were program directors felt was an idea whose time had come. All Things Considered was the standard-bearer of journalism. But most stations didn’t have a reporting staff, and most stations carried lots of classical music with this kind of tweedy, academic, erudite people who would say [affects refined voice] “And now let’s hear some Shostakovich.” “It’s Mozart hour today.” We saw the numbers during those hours decline.

A lot of us who were running stations said, “You know what? Opera is not going to be our future. Classical music is not going to be our future. Our strength is in our NPR news identity, so let’s build programs that attract a consistent audience all day long. Let’s give people a lot of content that they can tune in and find attractive and give money for.”

Danny Miller: Bill Siemering saw this opportunity for Fresh Air being the thoughtful arts and entertainment companion, very much like a newspaper. On Sunday, you get the arts section. We’re the arts section. ATC is the front page.

Robert Siegel: In part because NPR had gone broke [in 1983], there was interest in not just producing programs in Washington. I ultimately heard that Terry was very, very good, and I was interested in her for two reasons. One was to get a very, very good program distributed by NPR that didn’t lean on the same reporting staff of Morning Edition and Weekend Edition.

Also, there was a lot of pressure to move All Things Considered to a 4 p.m. start and to make it a two-hour program. I was terrified of our starting at 4 p.m. The idea occurred either to me or to Bill that if Fresh Air were on, it could be a great lead-in to All Things Considered. I said, “Let me hear the program.”

I listened to a few interviews of hers and I was really impressed. I was blown away by it.

[Fresh Air debuted as an hour-long national daily show on May 11, 1987. Siemering left WHYY just after that. He says he was “forced out” by WHYY management.]

Terry Gross: [On whether she was nervous going national] Oh, God, yes. Hell, yes. It felt like suddenly you have this huge audience and they’re gonna be judging you right away — especially the program directors.

If you want program directors to keep paying for your show, they have to think that it has a listenership. They have to like it; they have to think it has some value. That’s all a lot of pressure. And it was a brand-new format. [Note: Originally, the first half was devoted to a live interview.]

Bill Siemering: It was a group decision, I think. It wasn’t like me ordering them. [Laughs] It was an opportunity: Let’s see how we can do this.

V. “A big ear”

Audrey Bentham, technical director, Fresh Air: At some point in the very late ’80s, early ’90s, like in Terry’s preamble, she would say, “Would you like me to describe the show to you?” so she could orient the guest. And there was a certain tipping point: “Of course I know what Fresh Air is!” These actors in L.A., they sit in their cars a lot. They listen to the radio, and it just snowballed.

Robert Siegel: [NPR] had become family radio. We were something you could listen to while your school-aged children are strapped in the back seat of the car. Having this blaring at their ears, you would not get a Howard Stern riff on jerking off that you would then have to explain to your children.

Terry Gross: There weren’t a lot of long-form interview shows. When we went national, I don’t think there were any NPR long-form interview shows like ours. So, I think the real estate was available. I think the timing worked out well. I was more visible than I’d be now. I wasn’t competing with celebrity podcasts.

Michael Lewis, journalist, author (The Big Short, Moneyball), frequent Fresh Air guest: She reaches everybody who will buy a book. It is shocking the effect it has. The effect is temporary, but it’s a massive spotlight being shined on your book out of the dark.

Mark Vogelzang: Oh, the boxes of books just arrived en masse, even before the national show.

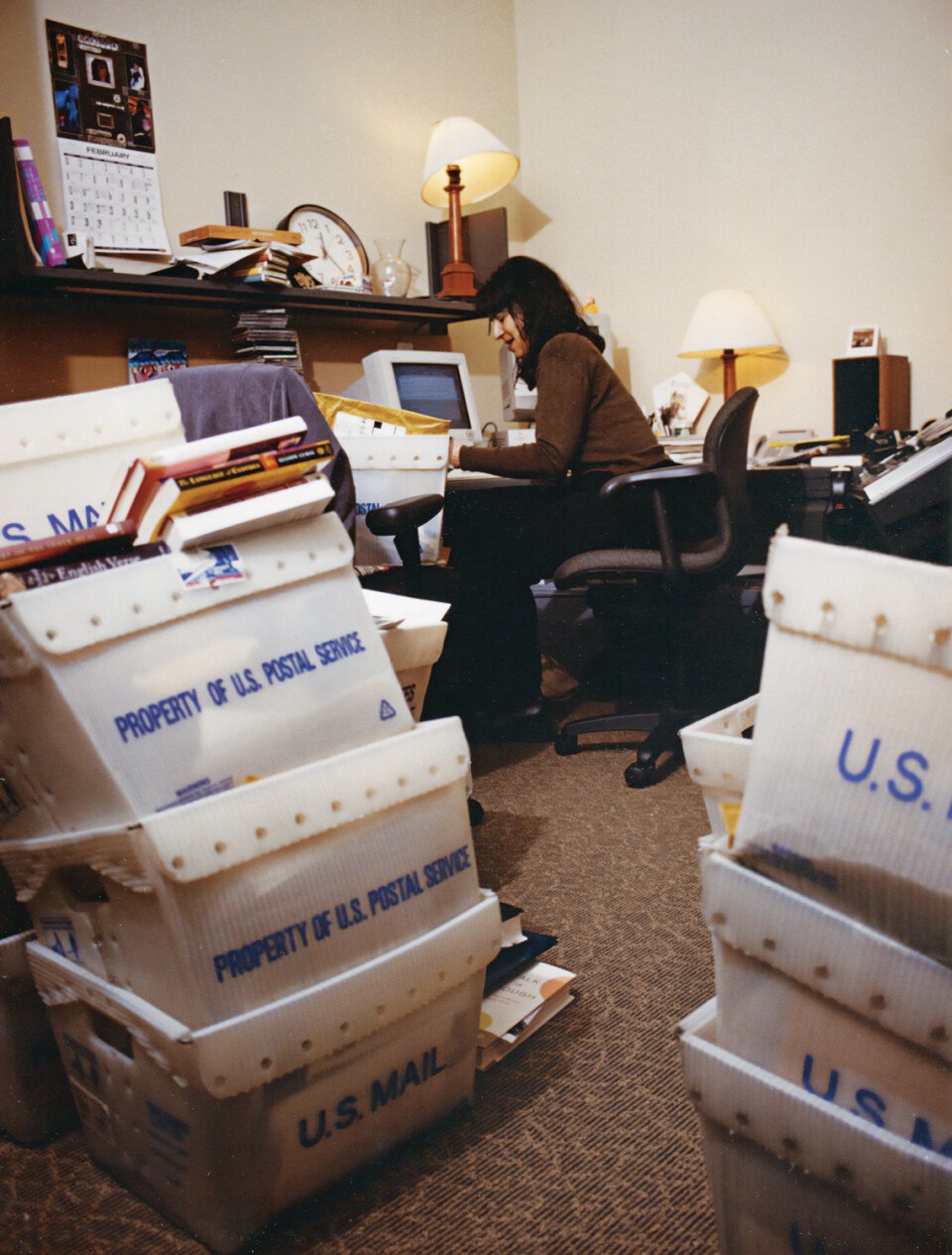

Amy Salit sorts through the mail in the mid-’80s / Photograph courtesy of WHYY

Heidi Saman, producer, Fresh Air, 2010 to 2024: I don’t know how many emails I was receiving a day — so many pitches.

Clay Ross, guitarist and singer in the band Ranky Tanky, who appeared on Fresh Air in 2017: I can’t really overstate what a profound impact it has. We immediately received thousands of orders for our debut album, and I spent the next several weeks trying to get the inventory shipped out, because I was actually shipping them out myself.

Audrey Bentham: I can think of hundreds of times where the guest has said, “You’re making me say things I’ve never said before.” There’s an intellectual exploration happening that gives birth to bigger ideas. I think that’s a function of Terry’s listening, her preparation. You’re teasing out something new that hasn’t already been covered a million times.

Terry Gross: I’ve always thought of myself as a big ear when I’m doing an interview. My antenna’s up; I’m listening intently. I’m looking at my notes; I’m writing things down. I’m deep in thought.

Michael Pollan, journalist; author, The Omnivore’s Dilemma; frequent Fresh Air guest: She’s not just harvesting quotes. She wants an interview to have the arc of a story, a beginning, middle, and an end. She’s shaping something.

Terry Gross: There’s a whole lot of information, and I want to organize that into some kind of narrative structure so that the questions and answers build on each other. But if somebody leads me in an interesting area or tells me something I didn’t know, I’m going to follow them. But I always have something to come back to. I have a structure in mind that I’m welcome to throw away.

Michael Lewis: I feel that I’m following dance moves. You walk onto the stage, she grabs you, the music starts to play, and you’re just following. It’s odd. I’m coming on, generally, as sort of the expert or the person who has written the book or the article. But I don’t feel like the expert. You don’t feel like you know things she doesn’t know and she’s about to learn them from you. Because she has done all the work before. There is no other person who interviews me who makes me feel that way.

Heidi Saman: I worked there 14 years. Every time we started an interview, I truly had no idea where she was going to go with it. That’s her magic. She’s listening on a level that is very unique.

David Marchese, staff writer, the New York Times Magazine; co-host, The Interview: It’s not just that she learns about the people she’s talking to, she then has ideas about those people based on what she’s learned. Her ability to synthesize the research into intelligent questions is very apparent and distinctive. It seems like that should be a basic tenet of interviewing for journalists, but it’s not — and she does it exceptionally well.

Bill Marrazzo, president and CEO, WHYY: She’s really a vessel that allows you or me or any other listener to have a direct conversation with one of her guests.

Clay Ross: Nine times out of 10, you’re talking to a journalist writing a piece for a local paper that has done no research into what you do. They ask the same questions over and over again. How did you form? What kind of music do you play? Tell me about touring. She was asking deeper questions about our culture and about our relationship and how a group like ours would even come into existence. She was asking the kind of key questions I think would help a listener discover us in a meaningful way.

Ken Tucker: You’d see her, she’s got a bagful of books. In previous years, it would be filled with CDs and albums. To me, her life and her work were completely entwined in the show.

Terry Gross: It was a cart. On wheels.

Mark Vogelzang: I had to head out the door at a certain time to catch the SEPTA train home and my kids coming from school. I was always running and Terry was always, of course, working late. She had this amazing capacity for excellence and research. Did I worry about her? Yeah. But who was I to say, “Make sure you take your vacations,” or anything else? Terry was head and shoulders above all of us.

VI. “We’re trying to figure out what the future is.”

Terry Gross interviews Seth Meyers in 2017 / Photograph by Paul Loftland

Fresh Air has won two Peabody Awards. Gross received a National Humanities Medal from President Barack Obama in 2016. Her voice has been featured on The Simpsons — twice.

But time provides no immunity, even for an institution as beloved as Fresh Air. Gross, 74, has reduced her workload, especially after her husband, writer Francis Davis, got sick in 2021. He died in April.

Tonya Mosley was named co-host in April 2023. Gross has no plans to retire, but Bill Marrazzo, WHYY’s president and CEO, has started succession planning “in a very low-key way.” There are more pressing concerns.

Bill Marrazzo: For all the virtues of noncommercial media, which is what public radio is, it is not immune from the pressures of a free-market economy, which includes the high likelihood that if something is succeeding, it’s going to get copycatted. We have been able to beat those competitive pressures back. I think the age of the program matters, and the brand equity of the show — and Terry herself — has been a condition precedent for shielding this franchise against those sorts of competitive pressures. But they’re real.

Terry Gross: We’re doing more social media. We’re trying to figure out what the future is and head in that direction. Tonya has really been pushing us in that direction. I think she’s been really right to do it.

Tonya Mosley, co-host, Fresh Air: Over time, the data has borne this out even more — that visual podcasts are super-important for people to understand the authenticity of a product. Now, where does this come in with Fresh Air, a show that has for 50 years been helmed by a woman who part of her lore is that she is not in front of a camera, and, in fact, not even in front of the guests?

As someone who has also been in front of the camera and understands that power of the visual language, we’ve already started building up my studio [in California]. So my guests come here; it is video. We’ll be providing that video content. And why that is important is because I do believe that is going to bring an entirely new audience to the table.

YouTube over-indexes now as the number one podcast player in the world. It’s the number one place people are going for podcasts. So if they go to YouTube and type in “Fresh Air,” what is going come up for them? Nothing, at this moment.

Bill Marrazzo: To maintain the vitality and the viability of Fresh Air in a changing media marketplace is to recognize that you’ve got to serve it up in a format that makes sense to a particular generation of consumers. Not to prostitute or compromise the editorial nature of the experience itself, but to present it where people are looking for it.

Tonya Mosley: We need human connection. We need conversation. We need that relation to each other. It’s actually a human need; it’s not a want. So I think that at its core, Fresh Air continuing that legacy but understanding that it may look different and feel different is where we are. But I don’t have the answers to all of what that looks and feels like.

Fresh Air co-host Tonya Mosley with guest Walton Goggins in May 2025 / Photograph by Walid Azami

Kyra McGrath, executive vice president/president, new ventures and enterprises, WHYY: Just figuring out this whole video thing. Do we post a whole episode of Fresh Air, or do we cut it up and put it on Instagram and YouTube and TikTok? How often do we post it? And what are our goals in terms of increasing our followers? And then how do you take those followers and get them to come along and be supporters? There are all these questions.

Terry Gross: I’m doing some video. But as somebody who’s always been an audio person and who’s really kind of believed in the simplicity of it and in the beauty of sound, I hope audio survives.

Ken Tucker: In her own way, she’s as much of an artist as anybody she interviews, and one doesn’t like to know a lot about artists you admire. You sort of like the mystery that’s there.

Terry Gross: The first time a journalist asked to have me photographed, I declined. I really didn’t want to be seen. I wanted every listener to create me in whatever form they needed, in whatever form felt comfortable for them. It wasn’t that I didn’t want to be recognized. I just didn’t want to be typed. I didn’t want people to think, Oh, she wears her hair this way, therefore she believes this, and therefore she hates that. I just wanted to be as free from being boxed in, in listeners’ minds, and just to be liberated from my body.

Kyra McGrath: Ira Glass [host of This American Life] has much more of an interest in being an entrepreneur. Terry doesn’t. Terry just loves what she does and wants to do that.

Sam Fragoso, host, Talk Easy with Sam Fragoso: I just don’t know who would be doing the kind of interviews that I do and couldn’t be influenced. She feels like oxygen or water. I do not think people know the depth of what she does. As someone who makes 52 episodes a year, as I do, I’m just so impressed by her consistency. To do something that much, that often, and that well, it’s really hard. It takes everything out of you.

Terry Gross: Well, you know, I gave up a lot to do the show. I don’t have children. I couldn’t imagine having children or a child, or even a dog or a cat or plants, and hosting the show. After I moved to Philly, I just got rid of my plants. I wasn’t paying any attention to them.

I set aside very, very little time for a social life or for pleasure. And Francis, my husband, he wasn’t a very social person. He didn’t love groups. I had so much tumult in my life that on the weekend, I just wanted quiet: go to a movie, go to a concert, have dinner, just me and Francis. It suited both of us. I had no free time. I was working all the time, but it was always worth it because I really loved doing the show. It was very, very fulfilling — and still is.

In one nightmare I’ve had over the years, I was so frustrated by so much work that I decided to quit. And then either in the dream or first thing in the morning when I’d wake up, I’d go, “Oh, no! Why would I do that? Why in the world would I do that?” So that was always very sobering if I felt too overwhelmed. It’s like, Do you want to live a life without Fresh Air? And the answer was always no. No.

Published as “Air Time” in the September 2025 issue of Philadelphia magazine.