When Philly First Caught Baseball Fever

Just in time for the Phillies’ regular season, a new book tells a true-life tale of baseball, mascots and murder in our city during Prohibition.

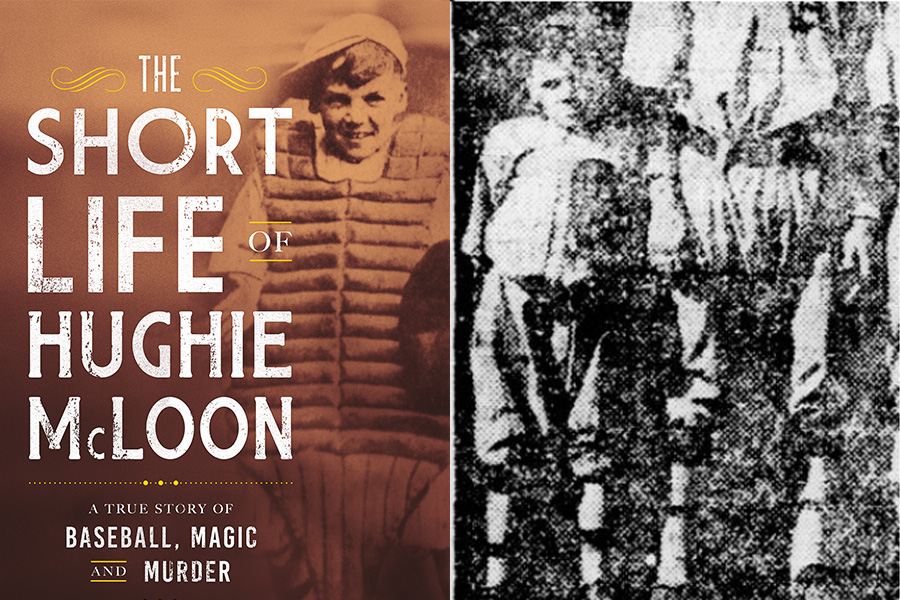

Hughie McLoon (right) shakes hands with Connie Mack, manager of the Philadelphia Athletics

In The Short Life of Hughie McLoon (Sutherland House), journalist Allen Abel tells the story of a South Philly kid, born in 1902, who suffers a tragic playground accident that leaves him dwarfed and hunchbacked, talks his way into a job as batboy for the Philadelphia Athletics (who rub his hump for luck), becomes a boxing manager, makes his mark in politics, opens a speakeasy, serves as an official “smeller” for police booze raids, and winds up murdered, shot to death on the sidewalk outside his illicit establishment at 10th and Cuthbert at the tender age of 26.

It was a helluva life, and it makes for a helluva story, spun out against the backdrop of Prohibition, sports idols like Jack Dempsey and Babe Ruth, dirty politics, and the buildup to World War II. But the real fun lies in Abel’s minute attention to the city itself; he peppers his book with names and addresses and snippets of history that pile up into our shocked recognition that these gambling, gin-soaked ne’er-do-wells are our great-great-grandparents, scrambling to make lives for themselves and seeking distraction in “the sudden, perfect green of [outfield] grass against the city’s grime.” Here, a few of those snippets.

A Hometown Rivalry

In the year of McLoon’s birth, the A’s were riding high, unlike their hometown rivals, the Phillies. The A’s drew 17,000 fans to a doubleheader at Columbia Park on September 10th in a pennant race against the St. Louis Browns. (They won both games.) The Phillies, playing that same afternoon at the Baker Bowl, had an attendance of 172. The A’s would be a Philly team until they decamped to Kansas City in 1955 and from there to Oakland, in 1968. The Phillies stayed put.

McLoon was part of the tail end of a long line of “lucky midgets.” Abel traces “a macabre cult of littleness sweeping human history from the stumpy god Bes of the Egyptians to the ‘lucky hunchback’ mosaic at ancient Antioch to Tyrion Lannister in Game of Thrones.” Other members in good standing include Victor Hugo’s Quasimodo, opera’s Rigoletto, and hunchbacked Philip Wakem in The Mill on the Floss. It was in 1863 that Lavinia Warren married “P.T. Barnum’s prized dwarf, General Tom Thumb.” Abel cites a number of disabled children, including McLoon, who were for superstitious sports gods (and who’s more superstitious than a sports god?) “the karmic equal of a shaman or a Gypsy or a Hindu fakir.” Today, we call them “mascots” — a name taken from La Mascotte, a comic opera that toured America in the 1880s. Any deformity would do: A team called the Wolverines employed a boy “said to have been born with a full mouth of teeth.”

Ty Cobb, batting champion of the American League for nine years in a row, “kept as his personal mascot an African-American boy whom he christened ‘Li’l Rastus,’ transporting him from game to game in a ventilated steamer trunk that he stashed under his sleeping-car bunk and his hotel bed on road trips through the Jim Crow League.” According to star Giants pitcher Christy Mathewson, “A hunchback is regarded by ball-players as the best luck in the world. If a man can just touch that hump on the way to the plate, he is sure to get a hit. … ”

Left: The cover of Allen Abel’s new book, The Short Life of Hughie McLoon. Right: McLoon pictured with the Athletics in the Philadelphia Inquirer in September 1917.

Alcohol and Olive Oil

As the century turned, the nation was torn over whether to prohibit the sale of alcohol. Former White Sox center fielder Billy Sunday, now a thundering, flamboyant prohibitionist, visited Philly in January 1915 and preached the dangers of drink from a “temporary timber tabernacle” on the new Ben Franklin Parkway to crowds of 10,000 and 20,000 as often as twice a day. When he and his wife left their rental quarters at 1914 Spring Garden Street after two months, their landlord sued them for $3,034.75, claiming they’d trashed the place and that bottles of gin and whiskey he’d left in a padlocked trunk room were empty and two dozen whisky glasses and 38 beer mugs were missing.

McLoon, alas, didn’t prove terribly lucky in his stint as the A’s mascot. In Ring Lardner’s baseball novel You Know Me Al, the wife of fictional pitcher Jack Keefe laments to him in a wail: “Oh Jack, it’s in the paper. They have traded you to Philadelphia.” McLoon moved on to bringing luck to a professional basketball team in North Philly for which he once slicked the opposing team’s half of the court at Moose Hall on North Broad Street, near the Temple campus, with olive oil. “The teams,” Abel writes, “were not yet in the habit of changing ends.”

Hughie with boxer “Lanky” Ralph Smith in 1927.

Send In the Marines

In 1923, after Prohibition took effect, Philly Mayor W. Freeland Kendrick brought in U.S. Marine Corps Brigadier General Smedley Darlington Butler, also known as “the Fighting Quaker” and “Old Gimlet Eye,” a two-time winner of the Medal of Honor, to clean up the city. Butler created for himself a handsome uniform that included a theatrical blue cape with gold trim and “a flaring red lining,” then hired McLoon as his “smeller,” to discern whether liquids turned up in raids were illicit booze or not. Butler didn’t last long. He later told a biographer, “The whole history of my two years in Philadelphia is filled with incidents of people approving my work until it interfered with their own violation of the law.” Plus ça change …

In September of 1926, McLoon held the signs announcing the number of each three-minute round in a battle royal as his friend Jack Dempsey defended his world heavyweight crown in an outdoor ring in the swamps south of Packer Avenue. His opponent: James Joseph “Gene” Tunney, the “Fighting Marine,” a philosopher of sorts would marry a millionaire’s daughter and go on to count George Bernard Shaw as a friend. Tunney won.

There’s much, much more to this book, but we’ll leave you with this: After McLoon was gunned down, he was taken to Jefferson Hospital, where he died. More than 15,000 people turned out for his viewing in a house on Shunk Street near Broad. His headstone reads: “Former Mascot of the Athletics.” His funeral was paid for by Max “Boo Boo” Hoff, a boxing impresario and gangster who ran Philly’s bootleg liquor empire. His murder was never solved.