For 25 Years, Jimmy Dennis Was on Death Row. Then One Day, He Wasn’t.

The Philadelphia musician spent the prime of his life in prison for murder, until the courts said he should never have been convicted. Now he’s trying to recover what he lost — time, relationships, his sense of self — while living through a new kind of lockdown.

Jimmy Dennis walks down a set of steps near the Abbotsford Homes where he grew up. Photograph by Neal Santos

Jimmy Dennis lives in a bubble.

In the age of COVID, that’s not so uncommon. But even amidst this winter’s tightened restrictions, Dennis’s bubble is a bit more constricted than most. It’s just he and his girlfriend — his childhood sweetheart, Corby Johnson — and he’s not comfortable telling people where in the city they share a home. Twenty-five years on death row prepared Dennis to keep his circle small.

Every day, whether he intends to or not, Dennis wakes up at 6 a.m. In prison, 6 a.m. was time for count, a ritual wherein guards tally the inmates to make sure they’re all where they should be. These days, after his early rise, he takes his time in the shower. Dennis even does a few vocal warm-ups. It’s a simple pleasure, but when you’ve grown accustomed to washing quickly in a stall the size of a phone booth, a few extra minutes to sing in the shower isn’t something you take for granted.

His go-to breakfast is fried eggs and spinach, and when he wants to treat himself, it’s shrimp and grits, a dish his mother cooked for him right after his release. Since getting out of prison, Dennis calls each day to check in on her, his two adult daughters and his grandchildren. He visits them — socially distanced — when he can. But on the way, he’s careful to remain below the speed limit, and he avoids staying out too late at night. He’s terrified of anything that might result in a police encounter.

He hates exercise, but he does it, sometimes spending his early afternoons working out. It’s part of an effort to lose 120 depression pounds he gained in prison. He does regular virtual sessions with a therapist who’s been helping him with the post-traumatic stress disorder that makes it difficult to sleep. And when he can’t sleep, he writes music — a passion that, more than anything else, makes him feel free.

But talk to Dennis, who’s spent the past three and a half years living on the outside, freed by a series of court decisions, and it becomes clear that prison isn’t something you just leave behind. Dennis was only 22 and an up-and-coming R&B musician when he was convicted of the 1991 murder of a 17-year-old girl in Philadelphia — a crime he has always maintained he didn’t commit. By the time he walked out of prison a free man in 2017, the world had morphed into something almost unrecognizable: wi-fi. Uber. FaceTime (FaceTime!) with his daughters. Over the past couple of years, he’d been slowly learning to navigate this new world, with Johnson’s help. Then the sudden arrival of COVID-19 and a wave of protests over police killings of Black people made the 50-year-old Philly native feel like he was returning to his old world.

For him, transitioning from a cell to a bubble has been more than an inconvenience. Terms like quarantine, social distance and lockdown contain deeper and more painful meanings. “To have these restrictions placed on you, and to walk outside my neighborhood and see the National Guard — it’s felt very eerie, it’s felt very restrictive, and it’s felt very much like prison,” says Dennis. “Because of my PTSD, I have panic and anxiety attacks often. A lot of the stuff that I was already dealing with, this has heightened it.”

Amid all these challenges, Dennis is facing yet another: He’s filed a civil suit against the City of Philadelphia, an attempt to get back part of what he’s lost. And Dennis has lost a lot.

When he walked into a Philadelphia courtroom on October 16, 1992, Jimmy Dennis still felt a flicker of hope. He was facing a murder charge, but he held onto one thing: He knew he didn’t do it.

The prior months had been a whirlwind. And it all started with a rumor.

A 17-year-old girl named Chedell Williams had been shot and killed in the Fern Rock section of North Philadelphia after a man attempted to steal her earrings. A few days after Williams’s murder, while police were following up on leads, they received a tip from someone who said he heard it was “Jimmy from the Abbotsford projects” who had pulled the trigger. But when police started asking questions, the tipster said the information came from someone else, and that person had heard it from someone else still. “It was like a rumor of a rumor of a rumor,” says Amy Rohe, one of Dennis’s former criminal defense attorneys.

Photograph by Neal Santos

The tipster said the Jimmy he knew from the Abbotsford projects was Jimmy Dennis. The shooter was described by witnesses as about as tall as Williams, who was five-foot-10. Dennis is five-foot-four. Still, police closed in on him.

Of the 20 to 30 people in the area at the time of the killing, the police only took statements from nine. According to Rohe, five witnesses who didn’t pick Dennis from a photo array of potential suspects weren’t called back for the lineup. Four witnesses who did give tentative identification from the photo array were. “As you can imagine, they had already seen his picture in the photo array,” Rohe notes. “So they picked out the person that they recognized the most.” One of those four witnesses picked someone other than Dennis from the lineup.

On November 23, 1991, Dennis was arrested for Williams’s murder. When he gave his statement, he declined his right to an attorney. He also had an alibi: He’d been traveling from his father’s house to the projects at the time of the murder. He even waved to one of his neighbors.

Still, Dennis would spend nearly a year in county jail awaiting trial. While he was there, the story of Williams’s murder sparked a media frenzy. There had been a rash of jewelry robberies in Philly, and this shooting had occurred in broad daylight at SEPTA’s Fern Rock station as dozens of people stood nearby. In the court of public opinion, Dennis was a heartless, brazen killer. Behind bars, he faced attacks and threats from guards and prisoners alike.

“I had already been through some horrible ordeals,” he recalls. “I was being jumped, and I had to defend myself. And then I was being taken to court. The spotlight was on me for something I didn’t do.”

The day of the trial, media filed into the front-row seats in the packed courtroom. Elsewhere in the gallery were Dennis’s family members, former classmates and childhood friends. Their presence fueled what little hope he had: “I still believed, as I was walking into that courtroom, that I would get my life back.”

But Dennis’s lawyer at the time didn’t make a strong case. Dennis’s family had pulled together some $17,000 to hire a private attorney. But unlike public defenders, who sometimes find themselves overburdened with more cases than they can adequately defend, Dennis’s lawyer, Rohe says, voluntarily took on a heavy caseload — and did little to defend Dennis. A judge who later reviewed Dennis’s conviction cited basic failings of his defense counsel.

“Honestly, I wish Jimmy had a public defender. They would have done a much better job,” says Rohe, who joined Dennis’s case eight years after his conviction.

Though there was no physical evidence, no DNA evidence, no weapon, and no known connection between Dennis and the victim, a jury found him guilty of first-degree murder.

“My world was rocked when the verdict was read,” Dennis says. “I remember it feeling like somebody had just taken all of the wind out of my body.”

Dennis recalls hearing his mother sobbing, loudly. His older sister, Hope, rocked back and forth in her seat, crying uncontrollably. His older brother, Greg, and several childhood friends he’d never seen shed a tear were suddenly weeping. His daughters, then just one and four years old, certainly didn’t comprehend what had happened to their dad, but their eyes, too, filled with tears. “It was as if everybody started crying all at the same time,” Dennis remembers. “I will never get that image out of my head.”

“My world was rocked when the verdict was read. I remember it feeling like somebody had just taken all of the wind out of my body.”

Dennis cried, too — intensely. It’s a detail he says nearly all the media covering the case failed to include, because “that wasn’t the narrative they wanted people to believe.” Three days later, on October 19, 1992, he returned to the same courthouse and was sentenced to death.

Life on death row is hard for anyone. For a 22-year-old just learning what it means to be a grown man, it was a horror. “The conditions on death row are deplorable,” says Dennis. “It’s not fit for animals, let alone humans.”

While prison is, in theory, designed to rehabilitate offenders, one thing became clear to Dennis: The goal of death row isn’t rehabilitation — it’s suffering. As he describes it, he was in the equivalent of a cage, on lockdown for about 22 hours a day. He got an hour or two in the yard and the library, but even there, he was still caged. He got 10 minutes to shower on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays. Meals were served through a slot on heavy plastic trays that are rarely clean and often covered with racist epithets carved by other inmates. He was allowed one 10-minute phone call per month. In these conditions, many of Dennis’s fellow inmates showed signs of developing mental illness. Over time, he did, too.

“I saw people go crazy. I saw some people commit suicide,” Dennis recalls. “It felt like every single day I had a gun pointed to my head and someone was playing Russian roulette.”

On his worst day, Dennis received heartbreaking news in the most inhumane way. “I’ll never forget that horrible day,” he says. “One of the guards abruptly came to the cell door and just yelled out, ‘Your dad died’ and walked away. It was that harsh, that cold, that devastating.”

Before Dennis’s father, James Murray, developed Alzheimer’s disease, he would frequently make the roughly 10-hour, 600-plus-mile round-trip trek to SCI Greene, the maximum-security prison south of Pittsburgh where Dennis served most of his sentence. “My dad used to bring my mom and my daughters up every month,” Dennis recalls, “until the point where he was so affected by dementia, he couldn’t anymore.”

Before his conviction, Dennis had been a member of a promising R&B singing group, Sensation. His love of music came from his father. Dennis’s parents were members of the Church of God in Christ, and as a child, he’d often sit on the piano or organ while his father rehearsed. He was his dad’s little shadow. “We used to dress alike,” he recalls, smiling at the memory. “I used to carry his briefcase with his music sheets when he would play for various churches, and the choirs would sound so beautiful.”

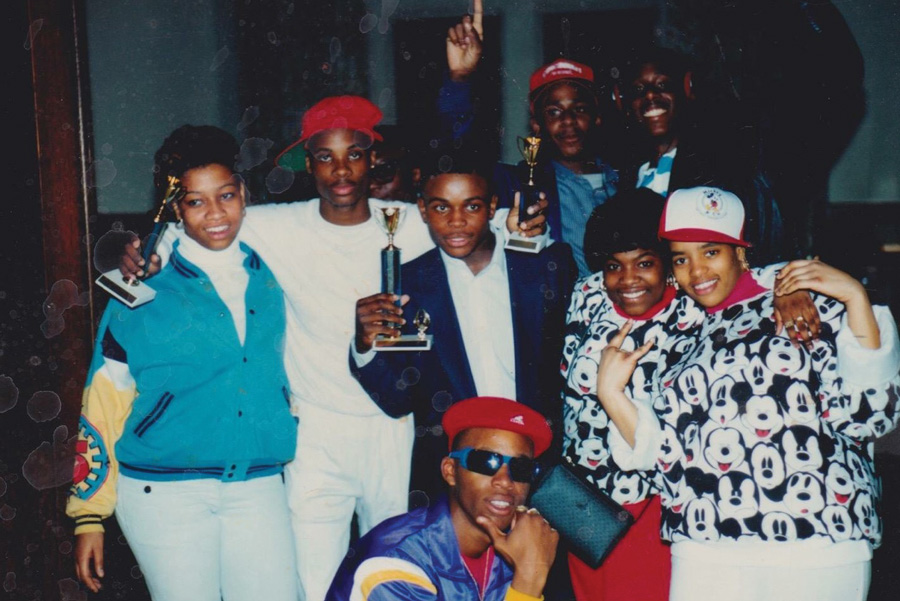

A young Dennis (center) and members of Sensation show off trophies won at a citywide talent show in 1989. Photograph by Neal Santos

His sister Hope still remembers the day their parents bought Jimmy his first drum set, around his fifth birthday. “It was set up right in the living room, so we all had to endure him learning to play,” she recalls.

When Dennis was in fifth or sixth grade, the family began to notice that he had a great singing voice. In middle school, Dennis joined the District Six Festival Choir, comprised of the top singers from schools throughout the tri-state area. It’s where Dennis and Corby Johnson first met.

“Jimmy was a very shy, handsome young man. We used to eyeball each other at rehearsals,” Johnson recalls. “We’d be there for a few hours a day, and we would just sing all day long. Jimmy loved it.”

His conviction interrupted his musical career; prison took music away entirely. Amid so much despair, Dennis struggled to connect to his creative side. But he eventually began writing songs again. He would write more than 700 while in prison.

Dennis was occupied by more than just his music. He also had a burning desire to prove his innocence. He wrote to universities and organizations to request free law books and journals, and over the years, his cell began to resemble a legal library. He wrote letters on prison pen-pal sites laying out the details of his case, hoping someone would respond. Over time, he amassed a loyal following of supporters who believed in his innocence, as well as a dedicated legal team fighting on his behalf. One of his earliest champions was Amy Rohe.

Rohe began representing Dennis in 2000, when she was just a few years out of law school. She and several lawyers from the Washington, D.C., law firm Arnold & Porter had taken on Dennis’s case pro bono. They spent years in state court, filing appeals and having them denied, systematically working through their options there before moving on to federal court. This legal process is called, morbidly, exhaustion.

“Death-penalty cases tend to drag on for years,” says Rohe. “The first judge we had at some point said, on the record, ‘There’s no rush in this case. It’s a death-penalty case. He’s on death row.’ We had to impress upon him that this is an innocence case and there is a rush, because he’s losing years of his life.”

Rohe’s team finally got an opportunity to present Dennis’s case to U.S. District Court Judge Anita B. Brody, who reviewed the case and in 2013 wrote a legal opinion overturning his conviction. In her ruling, Brody cited myriad flaws in both the case against Dennis and his defense, calling the whole affair “a grave miscarriage of justice.” Brody noted problems with the prosecution — including that it relied on “shaky eyewitness identifications,” “covered up evidence that pointed away from Dennis,” and ignored Dennis’s alibi — concluding that Dennis’s prosecution “was based on scant evidence at best.” She also cited issues with Dennis’s defense, highlighting his counsel’s failure to interview a single eyewitness in finding that the attorney “provided only a bare minimum defense.”

Shortly after the decision, Dennis’s legal team came to visit him at SCI Greene. Rohe held a printout of Brody’s decision up to the plexiglass for Dennis to read. “When I read the first paragraph — ‘James Dennis, the petitioner, was wrongly convicted of murder and sentenced to die for a crime in all probability he did not commit’ — I just started crying,” Dennis says, “and they all started crying, too. That first paragraph meant the world to me.”

Brody’s decision gave the district attorney’s office 180 days to hold a new trial or set Dennis free. Instead, the DA appealed.

“At that point, our team had been on the case for about 13 or 14 years before finally getting someone to listen,” Rohe says. “But having been on the case for that long, we weren’t naive enough to think it would mean he was going to walk out the door.”

Rohe and her team spent the next three years fighting the appeal. A three-member panel of the Third Circuit Court of Appeals initially overturned Brody’s ruling. That loss set the team up for one last Hail Mary: a request to have the entire Third Circuit Court of Appeals, 13 judges in all, reconsider the panel’s decision. “It’s extraordinarily rare to have it granted,” Rohe says of such an appeal. “You have to prove that the first panel of judges got it wrong. So we spent that entire time explaining to Jimmy that it was never going to happen. And he spent that time telling us that it absolutely was going to happen.”

As Dennis had predicted, his legal team won the right to be heard in front of the full court. On August 23, 2016, they won, in a 9-4 decision. On May 13, 2017, Dennis was released from SCI Greene. He’d spent close to 9,000 days on death row.

Sudden freedom doesn’t undo 25 years of injustice. Dennis deals with crippling paranoia. When he encounters people he knew before going to prison, it takes a few minutes for him to recognize and embrace them. He gets nervous if a car drives behind his for too long. And if Johnson double-parks to run into a store, Dennis worries the infraction could land him back in prison.

No one has had a better view of this than Johnson, who knew Dennis when he was young and has seen his transformation from joyful, doe-eyed choirboy to fearful shell of a man. Before his incarceration, Dennis was carefree, outgoing and friendly. Now, says Johnson, he lives a life tightly bound by an obsession with rules. He walks a fine line, never stepping out of bounds, always worrying about his freedom. To this day, whenever he leaves home, Dennis keeps a copy of Brody’s opinion in his backpack.

“He worries about the things people say could never happen, because the thing that people say could never happen actually happened to him,” says Johnson. “I know people like to think that you should just be so appreciative because you’re no longer on death row, and he definitely is. We all are. But it’s a whole different life out here.”

It’s a reality that nobody understands better than Anthony Wright, a fellow Philadelphian who spent 25 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit. In 2016, thanks to DNA evidence, a jury acquitted Wright of the 1991 rape and murder of an elderly Philadelphia woman that had originally put him behind bars.

“Jimmy worries about the things people say could never happen, because the thing that people say could never happen actually happened to him.”

Wright met Dennis at an exoneree event shortly after his release and was in attendance for what may have been Dennis’s best moment since winning his freedom. In April 2019, Dennis was one of several people honored at the annual conference of the Innocence Network, an affiliation of organizations dedicated to providing pro bono legal and investigative services in wrongful-conviction cases. It’s a refuge, says Wright, where exonerees finally get a break from “always being the elephant in the room.”

Exonerees are part of an exclusive club — one based in redemption but rooted in despair. Since 1989, when the National Registry of Exonerations began tracking such data, 2,699 Americans have been exonerated of crimes they didn’t commit. Ninety-six of those exonerees were convicted in Pennsylvania, where they were imprisoned for a combined 1,170 years.

Jimmy Dennis wears bracelets given to him after his release by one of his attorneys. Photograph by Neal Santos

The 2019 conference featured a keynote by members of the Central Park Five, a group of Black and Latino teenagers from Harlem who were wrongly convicted in 1990 of raping a white woman in New York City’s Central Park. When it was Dennis’s turn to walk the stage, Wright was front and center.

“Being from Philly, I wanted to be the first one to show him love,” Wright says. “So I pushed everybody out the way and I walked up to him and I told him I loved him. I told him, ‘Welcome home, brother.’”

“The very next hug that I got was from Raymond Santana of the Central Park Five,” Dennis recalls, “and he said, ‘Welcome home.’ It was a very good moment. It was a moment where I felt like some of the weight had been lifted off of my shoulders.”

Much of the heaviness Dennis feels is tied to the fact that at any moment, another innocent young Black person could end up where he once was. “It’s my duty to educate people and to let them know that I could be their brother,” he says. “What happened to me could happen to anybody, and it happened because of corruption.”

Patricia Cummings, head of DA Larry Krasner’s Conviction Integrity Unit, which is tasked with reviewing innocence claims by convicted offenders, concurs. She says that exoneration cases tend to involve both system errors and people manipulating that system for their own ends. “Too many people, whether they be prosecutors or other stakeholders in the system, still believe that our criminal justice system doesn’t make mistakes and is not corrupt,” says Cummings. “The starting point for us is that we know that’s not the case. The numbers tell us it’s not the case.”

Along with being victimized by the system, Dennis is a victim of place: Pennsylvania is one of only 15 states that don’t have laws to compensate the wrongfully convicted. It’s a wrong that State Representative Chris Rabb, who represents parts of Northwest Philadelphia, is trying to make right. In August 2020, he announced plans for a bill through which the Commonwealth would pay exonerees $65,000 for each year of wrongful incarceration. Rabb calls the state’s failure to compensate them “a hypocrisy of epic proportions.” He says the issue hasn’t been prioritized because so many of the state’s exonerees are poor Black men. “Federal prison is a torturous place to exist, particularly if you’re innocent, like Jimmy Dennis,” says Rabb. “If you have been wrongfully convicted of a crime and have been put in a box for years, you deserve compensation.”

Whether Rabb’s proposed bill would go anywhere in the state’s Republican-controlled legislature is anyone’s guess. Meanwhile, Dennis is in year three of a legal battle for compensation from the state, and as ever, he remains hopeful. For one thing, he’s being represented by Paul Messing, an attorney from the legal team that in 2018 secured a $9.85 million settlement for Anthony Wright in a civil case against the city — the largest wrongful-conviction payout in Philadelphia’s history.

But Dennis’s case is less tidy than Wright’s. Wright was exonerated based on DNA evidence and absolved of all charges against him.

After the Third Circuit judges threw out Dennis’s original conviction in 2016, he had two options: sit in prison while he awaited another appeal by the DA, which Messing estimates could have taken two years or more, or take a plea deal. In Dennis’s case, the DA agreed not to appeal to the Supreme Court if Dennis would plead “no contest” to a reduced charge of third-degree murder; he would then be released immediately for time served.

For Dennis, that was an agonizing decision.

He’d already lost his father, and now his mother was sick. While continuing to profess his innocence, Dennis took the deal.

According to Messing, that decision makes a claim against the city more difficult, because you can’t sue for unlawful arrest or malicious prosecution if the charges weren’t dropped or you weren’t explicitly found not guilty. Still, Messing sees another path to victory for Dennis. His civil suit hinges on a series of claims of “extraordinary misconduct” against the city and the detectives in his case, ranging from witness coercion and false testimony to the fabrication and suppression of evidence.

For example, the suit alleges that police relied on evidence they claimed to have collected from Dennis’s father’s home, including clothing supposedly similar to what eyewitnesses described the perpetrator as wearing. The clothes, though, vanished before the jury or Dennis’s lawyer could see them. Dennis’s attorneys also claim that officers withheld a document that could have corroborated his alibi.

Shannon Zabel, the assistant city solicitor for Dennis’s civil suit, says the city doesn’t comment on active litigation. Messing, however, remains confident that Dennis will win. “We have a mayor now who’s progressive and who talks about fairness in criminal justice,” he says. “We’re hoping that his administration follows through on that.”

It took two years to secure a settlement in Wright’s case. Dennis’s has already taken longer. In the meantime, supporters have set up a fund to help him stay afloat as he awaits the outcome. But even if he wins, his family says, he won’t be made whole.

“You could give Jimmy $10 million a day,” his brother Greg says. “Is that going to give him back the time that he missed with his mother, his brother, his sister and his kids? I hope he gets everything that’s due to him, but what’s really due to him is something more than you or I or anybody else could ever put in words.”

“Hopefully he’ll be able to get back into things, and hopefully his music is a way into that,” says Hope. “My prayer is that even though his whole life can’t be restored, if his dreams with his music can come true, then that would be awesome.”

In November, Dennis voted for the first time in a presidential election. He skipped the mail-in process and instead went directly to an early-voting location to cast his ballot in what he called “the most important election of my lifetime.” He doesn’t tell me outright which candidate he opted for, but he does say, “I’m certainly not voting for anybody that would pay to have my innocent brothers put in prison for something they didn’t do.” That’s a clear nod to Donald Trump’s 1989 purchase of more than $85,000 in newspaper ads calling for New York State to adopt the death penalty in the wake of the arrests of the Central Park Five.

When Dennis isn’t attending innocence-community events, he’s in the recording studio, relieving his pain through song. In 2020, he released his third and fourth singles in two years. “Hate the Skin I’m In” punches at the tension behind recent civil unrest and the need for movements like Black Lives Matter. His latest, “Tears This Year,” speaks to the trials of 2020.

Unlike in those dark early days in prison, Dennis now writes constantly, whenever and wherever inspiration comes. One of his producers, Michael Boykin, says Dennis possesses the one thing he looks for in any promising singer/songwriter: “A lot of artists get caught up in the hype, and their music gets pretentious because they try to do what they heard or saw some other artists do. Jimmy just wants to express what’s inside of him and to do that honestly.”

Dennis has plans to put out two albums in 2021. Beyond his own pending releases, a career goal is to one day work with the Gap Band singer Charlie Wilson. It’s all part of his plan to reverse the “false legacy” that has tainted his identity for more than two decades. And the fruits of that effort are beginning to show. Just last year, Dennis received a call from one of his lawyers. She had Googled her client, she said, and asked him, “When you look Jimmy Dennis up, do you know what it says?”

“No,” Dennis replied.

“R&B artist,” she said.

Learning that his searchable identity had gone from convict to free man to musician meant everything to Dennis. But, he adds, “That’s what it always should have said.”

Published as “For 25 Years, Jimmy Dennis Was a Death-Row Convict. Then One Day, He Wasn’t.” in the January/February 2021 issue of Philadelphia magazine.