For 40 Years, Philly Mayors Have Promised to End Poverty. For 40 Years, I’ve Watched Them Fail.

Administration after administration, their plans have solved nothing. This is what having a front-row seat to decades of political futility looks like.

For decades, our mayors have promised to end Philadelphia poverty, but they’ve all failed.

There are so many poor folk in Philadelphia that in March, City Council President Darrell L. Clarke announced a plan that would lift 100,000 of them out of poverty over the next four years.

One major part of the plan is to just hand them cash, à la Andrew Yang. “Call me crazy — I’m just optimistic this will happen,” Clarke said at the news conference.

Five months earlier, Mayor Jim Kenney made his own announcement on poverty. He boasted that the city’s economy had improved so much that 15,000 poor folks had left poverty behind. But when poor folks become working poor folks, it’s still a slippery slope.

When you live below the poverty line (currently $12,760 a year for an individual, or $21,720 for a family of three), every problem is a crisis. Housing insecurity turns into chronic homelessness. Poor schools become dropout factories. Job problems morph into long-term unemployment. Hunger intrudes. Irritations explode into violence.

Take COVID-19. Within 10 days of Governor Tom Wolf’s closure of all non-essential businesses, 645,000 Pennsylvanians, many thousands of them low-wage workers, had filed for unemployment.

Slip.

For poor working-class African Americans, COVID-19 combined with the misery of job uncertainties and the brutal slaying of George Floyd that touched off international protests over racial injustice and police brutality.

Slip.

But death was the far greater problem. Blacks are disproportionately contracting and dying from COVID-19 in large part because they make up the nation’s essential service workforce, with jobs in long-term care facilities, with delivery services and at grocery stores. They’re unable to quarantine and work from home. Either they worked and risked getting sick, or they didn’t work and risked slipping back into deep poverty. COVID-19 essentially became a life-or-death decision.

Splat.

If you don’t see this, it’s because your portion of the world is affluent, thriving, comfortable and white. You’re sheltering in place and working remotely. But if you see it, you wonder: How did Philadelphia become the poorest big city in America? How did everything just go to hell? You wonder: Why can’t we find the path out?

I’ve been wondering this for decades.

Not only does Philadelphia have the highest poverty rate of the nation’s 10 largest cities; more than half of the poor here are in deep poverty, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts. So I want to believe Clarke when he says he’s found the way out. Kenney added in his press release that the decline was evidence his administration is on the right path. I wanted to believe him, too. Just like I wanted to believe the other mayors before him when they said their administrations had found the city’s elusive path out of poverty.

Now, the city has to dig out of the economic mess wrought by COVID. And that means a lot of new promises are going to come forth from mayoral wannabes.

To become mayor, you must convince the poor who vote that you have the solution to fix their problems. You have to convince the affluent that your policies won’t disturb their economic well-being. Philadelphia has had 99 mayors in its history and currently has a large delegation of living ex-mayors — William J. Green III, W. Wilson Goode Sr., Edward G. Rendell, John F. Street and Michael A. Nutter. Together, this group — all Democrats, all male — made those very campaign promises. Taken together, they spent nearly four decades trying to reverse-engineer the city’s poverty problem and its concomitant issues.

They all failed.

“The seemingly limitless growth of our cities has come to an abrupt end.”

It was 1944 when one of the nation’s top urban sociologists, Louis Wirth, made this pronouncement. Truth be told, the city’s power elite knew in the early 1950s, when reform Democrats wrestled the reins of power from the city’s corrupt and contented Republican machine, that Philadelphia’s economic future was bleak. Everybody who could afford to was fleeing the city. Companies were leaving, and so were people — especially the healthy, the young and the affluent. Increasingly, what was left was poverty, urban decay and Negroes. Lots and lots of Negroes, like my grandparents.

Both sets of my grandparents were part of the Great Migration and arrived from the South in the ’20s, hopeful and poor. They settled in North Philly. My parents were Depression-era babies, born in the ’30s, and despite the country’s economic collapse, they described a good childhood of unlocked doors, going to movies on Ridge Avenue, and a close-knit community that watched out for each other.

But urban historians describe an altogether different 1930s North Philadelphia, calling it a crime-ridden slum of about 78,000 poor Negroes crammed together. This is what earned the area the nickname “the Jungle.”

I’m a third-generation Jungle resident. I was born a few years before the riots on Columbia Avenue and before President Lyndon B. Johnson declared “unconditional war on poverty in America.” I didn’t live far from the avenue, in a rowhome my parents worked hard to buy and maintain. It was our slice of the American Dream.

We weren’t blind to the problems. We had neighbors who, despite being violently unwelcomed, headed to the suburbs. We stayed because we couldn’t afford to leave. So we painted in the spring, swept the sidewalks in the summer. But we were using Pine-Sol to do economic battle.

On warm Sundays after church, my parents would pile us four kids into the car and take an afternoon drive out to some random verdant suburb. We would look wistfully through the windows at the large single houses on wide, litter-free expanses of grass. There was no broken glass on the playgrounds. No dog poop on the pavements. No gang members on the corner. No strong whiffs of fake pine in the air. It was surreal — a splendid isolation from trouble.

“Look at all that space,” my mother would say softly. We kids would all stare.

And then we would head back home.

President Johnson promised to clean up America’s Jungles. In his first State of the Union address, he said he wanted “not only to relieve the symptom of poverty, but to cure it and, above all, to prevent it.” Ultimately, the nation would spend trillions of dollars attempting to solve poverty. And then it got tired of failing. Because poverty wears blackface in America, it’s become a racialized issue. Conservatives questioning the efficacy of the civil rights movement, with its focus on righting race-based wrongs of segregation and discrimination, pointed instead to another problem: the morality of Black people.

They concluded that in the War on Poverty, Black people were their own enemy.

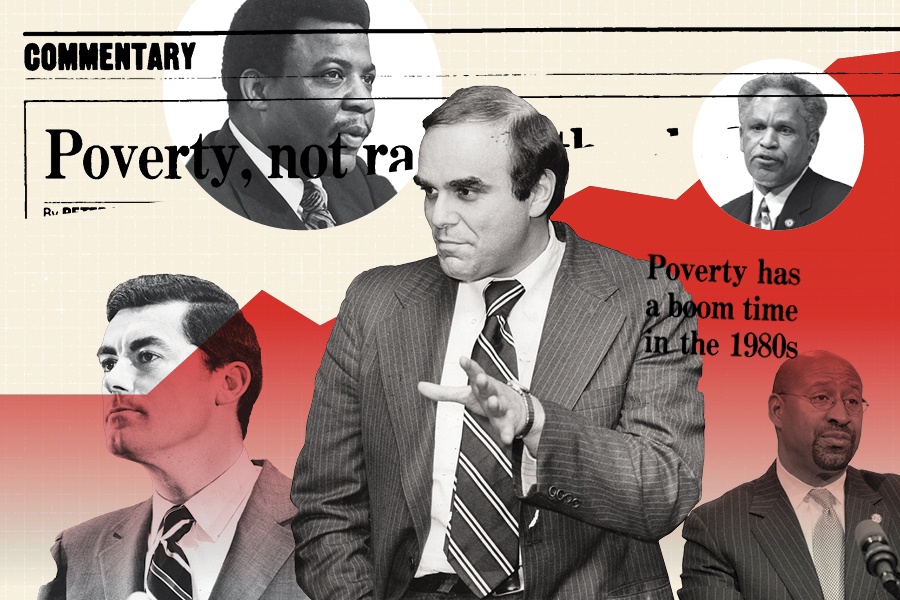

Mayor Bill Green

1980 — 1984

William J. Green III was as close to political royalty as you can get in Philadelphia. It was Green’s father — a Congressman and the namesake for the William J. Green Jr. Federal Building on Arch Street — who built the city’s Democratic machine and remade Philadelphia from a one-party Republican town into a one-party Democratic town. Green the son took over his father’s Congressional seat when Green Jr. died unexpectedly in 1963. A reform liberal, Bill III lacked his father’s everyman touch and zeal for retail politics.

Mayor-elect William J. Green introduces the team he’d assembled to tackle the city’s financial issues. Photograph by Salvatore C. DiMarco Jr./Temple University Libraries Special Collections Research Center

In 1971, he lost in the Democratic mayoral primary to Frank L. Rizzo. In 1976, he lost a U.S. Senate race against ketchup magnate John Heinz III. But three years later, amid strong anti-Rizzo and anti-Black-political-movement backlash, he defeated Charlie Bowser — one of the founders of Philadelphia’s independent Black political movement — in the mayoral primary. Bowser only got 10 percent of the votes in majority white areas; Green only got 20 percent of the votes in majority Black areas. Green went on to a landslide victory in the general election, becoming the city’s youngest mayor at 41.

Then he discovered that Rizzo, who’d ruled as if the city’s good times would never end, had handed him a fiscal mess.

Rizzo, a former police commissioner, was an old-time pol doling out favors in return for political loyalty. And it cost the city dearly. The school district was failing, the transit system was cratering, the city’s bond rating was in the toilet, and the Abscam scandal was all the news. Big Frank had been kind to the municipal employee unions — mainstay jobs of Philadelphia’s white middle and working classes — at the expense of the city’s budget. A month after taking office, Green laid off 1,300 city employees. “He said that Santa Claus doesn’t live here anymore,” recalls Phil Goldsmith, an Inquirer Pulitzer Prize finalist who worked in the Green administration as deputy mayor of policy and planning (and later in the John Street administration as managing director). “It had to be done, and Green had the guts to do it. He didn’t look the other way.”

A month after taking office, Green laid off 1,300 city employees. “He said that Santa Claus doesn’t live here anymore,” recalls Phil Goldsmith, Green’s deputy mayor of policy and planning. “It had to be done.”

But Green couldn’t stop companies from hightailing it out of Philadelphia. In February 1980, a newly formed workers advocacy group, the Delaware Valley Coalition for Jobs, held a hearing that led to a campaign to force plant owners to give 60 days’ notice before packing up and leaving. It was a contentious issue, and City Council overrode Green’s veto to pass a plant-closing notification law in June 1982. Green bellowed that they were “the worst legislative body in the free world.”

To make matters worse, Green was facing these problems just as a new president was coming on the scene — one promising to completely turn off the federal spigot that had been running since LBJ announced his War on Poverty. “One of the things I learned early on and firsthand is that the resident of the White House at any given moment makes a high difference in a city and in our lives,” ex-mayor Michael Nutter would explain in his memoir, Mayor: The Best Job in Politics.

Philadelphia lost its sugar daddy. “In this present crisis, government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem,” Ronald Reagan told the adoring crowds at his inaugural address in January 1981. At the beginning of Green’s term, the city’s poverty rate was around 20 percent.

I paid no attention to any of this until I got my first real post-college job — political reporter for the Philadelphia Tribune. I didn’t mention in my interview that I had never even voted. But the Tribune paid horrible wages back then, so it couldn’t be too picky.

On the other hand, at 21 years old, I was a new mom and a new wife. Broke with a toddler, I couldn’t be too picky, either. I got the job covering the mayor and his administration, City Council, the state Representatives and state Senators, Congressmen and Senators, the governor, grassroots campaigns, and more community meetings than I can remember. Crime, drugs, failing schools, corruption — you name it. One thing I learned early on: Every problem is a political problem.

By day, I was drowning in ideas declaring the right path forward — so many high-minded plans by experts touting tools to cure what ailed us. At best, they got a few inches of ink and then disappeared.

By night, I sat depressed in my teeny- tiny studio apartment in the Jungle, on North 30th Street, a few blocks up from Girard Avenue and across from the stinky Acme warehouse, feeling stuck in North Philly. I had learned in college that African Americans who stayed in the ghetto suffered not from being broke, but from personal and moral deficiencies that were passed down from generation to generation. I wondered if the experts got it right.

Mayor Wilson Goode

1984 — 1992

Mayor Green had kept a promise to appoint a Black managing director, the city’s second most powerful position. That was W. Wilson Goode, who tackled the job with unheard-of vigor. He seemed to be everywhere — every town meeting, every fire, every ribbon-cutting. Then, midway through his first term, Mayor Green announced that because he wanted to be home with his wife and infant daughter, he wouldn’t be running for another term.

“We sort of suspected he wasn’t going to run again,” says Phil Goldsmith. Right after that, Goode resigned and announced his candidacy. “If I run,’’ Goode predicted, “my candidacy will transcend race.” A Wharton grad, he declared that he would be like the CEO of a $1.6 billion corporation, and that his job was to provide services. In the aftermath of Watergate, the backroom practice of old-time pols handing out favors had fallen out of public favor. Elected officials were taking their talking points from corporate America. Quality management was the key to government efficiency.

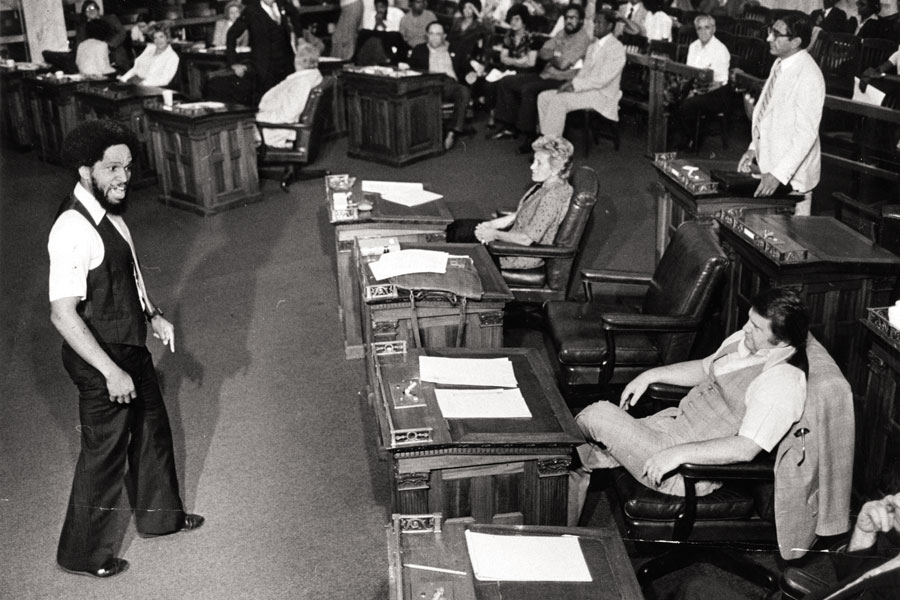

Ed Rendell and Wilson Goode, in their respective roles as district attorney and managing director, appear before City Council in 1980. Photograph by Barbara Patcher/Temple University Libraries Special Collections Research Center

Goode was the heir apparent of decades of Black independent political growth. Hardy Williams had run. Lucien Blackwell had run. Charlie Bowser had run. They all lost — but they had laid a foundation. White flight had left the city about 40 percent Black. And in a city that votes in Black and white, Goode had crossover appeal. ‘‘You didn’t have people saying they loved Wilson Goode, but nobody hated him, either’’ is how the late Frederick Voigt of the Committee of Seventy once described it.

But Goode wasn’t universally embraced. “Wilson Goode benefited from a political movement that he really did not have anything to do with,” says Linn Washington, a Temple journalism professor and a former Daily News City Hall reporter. Almost 40 years later, sitting in his office on Temple’s main campus, his frustration is still intense. “The movement in the late 1970s for Black political empowerment was driven by ire against police abuses and institutional racism like housing policies that Milton Street and others opposed. Though Goode had been involved in community efforts, he wasn’t out front on either anti-brutality or anti-institutional racism. Still, his elevation to managing director arose from that movement.”

“Goode turned into the public face of City Hall through the way he ran the managing director office,” says Washington, “literally showing up at big fires in the middle of the night, never too far from TV cameras. Wilson got elected mayor, from my vantage, more from being the Black candidate in the right place at the right time than from wide embracement of him as a popular or populist leader in the Black community — plus, he was seen as palatable to whites.”

My family was excited. I was working freelance now, mostly business writing. Every Saturday during the Democratic primary, a group of us trooped through North Philadelphia, knocking on doors and asking for donations. The enthusiasm was unmistakable, and folks were glad to give a dollar or two — $5 was a huge contribution. After collecting thousands of dollars, we held a party at the Clara Baldwin Neighborhood House on Sedgley Avenue and gave Goode a check.

The white press had made fun of Goode’s stuffiness and halting speaking style. The Daily News said he was “dull and humorless,” and Time said he had a “breathtakingly dull” speaking style. We didn’t care about that. Philadelphia was on its way to getting its first Black mayor. The son of a sharecropper could intuitively understand what it meant to live poor and then do something about it. We all thought power resided on the second floor of City Hall. Goode won 23 percent of the white vote but 97 percent of the Black vote.

In his book In Goode Faith, Goode describes the city he took over: “The Philadelphia I inherited as the city’s first African American mayor was on the verge of collapse, suffering a slow hemorrhaging death from high inflation, a declining population, and an anemic revenue base created by the exodus of thousands of jobs.”

“Poverty wasn’t an issue that people talked about during my administration,” Goode Sr. says on a gray January morning from his small but comfortable office at Amachi, a faith-based nonprofit that mentors the children of incarcerated parents. “The poverty rate in the early ’80s, it was much lower. Had I known that poverty would increase to the point it is now, I would have pushed the school district about training people for jobs for the future.” His headquarters is in a strip mall off Island Avenue in Southwest Philadelphia. His cadence is preacher-formal, and he chooses his words carefully. “I would have talked with the school district about trade jobs and would have pushed harder to push down racial barriers in the unions. But I didn’t have a crystal ball.”

By the time Goode left office in 1992, after two tumultuous terms overshadowed by the devastating MOVE bombing, the poverty rate was about 20 percent — higher than the rates in Bucks, Chester, Delaware and Montgomery counties combined.

Getting a job used to be as easy as walking out of one factory and into another.

You didn’t need a high-school diploma or a résumé and cover letter or references or a drug test. This is because once upon a time, Philadelphia was known as the “Workshop of the World.” Manufacturing dominated, employing about 45 percent of the city’s workers. It sopped up folks with a high-school diploma or less, taught them the job on the assembly line, and paid them okay wages. With the post-World War II prosperity, Black workers were doing better despite discrimination and segregated opportunities. In 1950, only two percent of Black workers in Philadelphia earned more than $4,000 per year. By 1960, that figure had risen to 12 percent. It wasn’t just Philly; it was all over the country. Alan Mallach, author of The Divided City: Poverty and Prosperity in Urban America, called the 1950s “the best years America’s industrial cities had ever seen.”

And then the jobs started disappearing, hundreds by hundreds. During the 1970s, Philadelphia lost 150,000 manufacturing jobs. Blue-collar men’s wages stagnated, and women entered the workforce in part to shore up their families’ economic foundations. Economists have called this the time when the economy stopped delivering for the working class.

“My father had a third-grade education,” explains Wilson Goode. “My mother had an eighth-grade education. But they were able to work — my father as a baler in a box factory, and my mother at St. Vincent’s Hospital.” That was in 1954, when the family migrated north. Goode’s point: Parents with the same educational profile today wouldn’t be able to find stable, family-sustaining work.

Goode pushed a trend that was a job killer: privatization. For voters, privatization promises better service at a cheaper price. For city workers, privatization is called getting fucked.

What Goode doesn’t mention is a trend he pushed that was a job killer: privatization. In 1988, during intense contract negotiations with the District Council 33 labor union, he threatened to outsource trash collection, a move that would have saved the city $32 million but cost it 1,300 to 1,700 jobs — many held by Black men with limited educations. DC 33’s boss, James Sutton, eventually backed down but the push for privatization would continue under Rendell.

For voters, privatization promises better service at a cheaper price. For city workers, privatization is called getting fucked.

Mayor Ed Rendell

1992 — 2000

When Edward G. Rendell first took over the mayor’s office in 1992, the city was, according to City Journal, “facing a cumulative deficit of nearly $1.25 billion over the next five years — larger than the entire budget of the city of Houston — and an immediate deficit that had grown to $230 million.” According to the incoming administration, the city was circling the drain, having hemorrhaged 400,000 people and 200,000 jobs over the prior three decades and raised taxes an astonishing 19 times in 11 years. It had the lowest credit rating of any major city in the country. “Goode was not a good financial steward, and then there was the MOVE problem,” charges Goldsmith. (Goode visibly bristles at this claim and vehemently denies the fiscal irresponsibility charge.)

It’s Rendell who gets national credit for reversing the city’s bleak situation.

A child of well-to-do Manhattan Jews, Rendell went to private school, then Penn, then Villanova Law. But he thrived in public service, becoming the city’s youngest DA, at 33, when elected in 1977. He was unrelentingly bullish on his adopted home, and despite his aristocratic pedigree, he had the common touch of Bill Green Jr., the father. He was also a media darling, like Rizzo, and could be counted on for a perfect quip. “When Rendell looked at a newspaper reporter, he didn’t see someone with the noble goal of informing the electorate. He saw someone hungry for the ultimate journalistic coup, making page one,” wrote the late Phyllis Kaniss in her book Media and the Mayor’s Race: The Failure of Urban Political Reporting.

However, Rendell was a practitioner of neoliberal economic theory, which embraces a free-market ideology on economic development. This trickle-down philosophy supported the idea that a vibrant Center City would attract businesses, which bring jobs. “Ed Rendell was the mayor of Center City,” says former Congressman Bob Brady, who’s been chair of the city’s Democratic Committee since the 1990s. Brady is a South Philly rowhouse guy, and this comment is made with a mixture of praise and disapproval. When Rendell talked of improving the quality of life, it was all Center City-focused.

Less discussed was how Rendell saved the city money by privatizing 49 city services, including City Hall custodial services, Art Museum security, parking garages and correctional facilities. In his 2012 book A Nation of Wusses : How America’s Leaders Lost the Guts to Make Us Great, Rendell wrote, “Government can and should be a force to improve the quality of people’s lives, to help create opportunity for those who have none, to help protect the most vulnerable among us who cannot protect themselves, to make sure that even the poorest and most downtrodden in our society have the basic necessities to survive.”

However, the essence of privatization is the opposite. You tell voters they’ll get more efficient services for less money. But the savings to some voters come out of the paychecks of others. This means decent-paying city jobs with benefits and pensions turn into poverty jobs with limited hours and lower wages.

But to elites, Rendell was a hero. Vice president Al Gore called him “America’s Mayor.” In 1996, American City & County anointed him “Municipal Leader of the Year.”

Rendell had perfect timing, because there was a Democrat in the White House who shared his views. President Bill Clinton read the political tea leaves and appeased the conservatives who pushed a narrative that said welfare wasn’t the solution to poverty, but rather the cause. “We should insist that people move off welfare rolls and onto work rolls,” he said as a candidate. “We should give people on welfare the skills they need to succeed, but we should demand that everybody who can work … become a productive member of society.”

Clinton, whom Toni Morrison had dubbed the first Black president, was also an avid supporter of privatization and would sign a welfare reform bill promising to end welfare as we know it.

Nobody ever talked about where these productive members of society would work.

Not long after Clinton’s Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act was passed in 1996, I went to work for the now-defunct Transitional Work Corporation (TWC), one of the city’s welfare-to-work organizations. Founded in 1998 by the state, the city, and the Pew Charitable Trusts, its mission was to provide job training and transitional employment to welfare recipients working their way off public assistance.

I was teaching by then, helping mostly Black and Hispanic mothers get their GEDs in preparation for work. Had these same folks been living in the 1950s, they would have gone to work for a manufacturer, and TWC wouldn’t have been necessary. But we had transitioned into the knowledge economy, meaning you needed a bachelor’s degree to get a good job and an associate’s degree to get an okay job. People with limited education and little work experience, with a criminal record and drugs in their piss, had a choice between one low-paying service job with unstable hours or another. It was food prep, some retail sales, janitorial work. All of it was shift work, less than 40 hours, and no benefits. It meant trying to raise a family on a fast-food worker’s salary.

The first thing we did was tell clients they had to stop smoking weed so they could pass a drug test.

The second thing was to help them redesign their lives so they could prioritize work — they needed child care, dependable transportation, doctors’ appointments that wouldn’t interfere. They needed to be available whenever the boss called.

What came next was always predictable.

“What about asthma — what about if my child has an asthma attack over the weekend and is in the hospital?” Someone always asked a question like that.

“Employers don’t want to hear about personal problems. They don’t want you missing work. ’Specially when you’re new and still on probation” was my standard retort.

Everyone would harrumph at that one. In this War on Welfare, I was the enemy, not the messenger.

“I am not going to work if my baby is sick” was the usual response, said with a roll of the eyes as others nodded agreement.

The third thing we had to teach them was socialization skills. Really, this meant how to wait on white folk and make them feel comfortable. “You have to smile,” I said.

Once, a student said to me: “Why would I smile if I ain’t got nuttin’ to smile about?”

“At the end of the Rendell era, Philadelphia is a city that has solved its age-old image problem but has hardly begun to address its reality problem,” wrote Kay S. Hymowitz and Fred Siegel, senior fellows at the Manhattan Institute, in their obituary for the Rendell administration in City Journal. Between 2007 and 2011, TWC received $32 million in Department of Public Welfare grants. And then it shut down. When Rendell left office and ran for governor, Philadelphia’s poverty rate was 23 percent.

Mayor John Street

2000 — 2008

Experts say your zip code determines your fate and that living in a bad neighborhood means your American Dream is over even before you’re born. I was raising three sons in North Philadelphia. They were fourth-generation, but it wasn’t easy. Nothing seemed to work well — not schools, not playgrounds, not libraries, not health centers. Clearly, inner-city neighborhoods needed help, and help wasn’t forthcoming from Rendell, who was focused on Center City — just five percent of the city by size.

John F. Street promised to focus on the other 95 percent.

Before he was mayor, John Street was a firebrand City Councilperson. Photograph by Charles J. Tinney/Temple University Libraries Special Collections Research Center

There are a lot of criticisms leveled at Street — that he was pugilistic, prickly, ethically challenged. One good thing that’s been said is that he understood the issues of poor neighborhoods. He had been an aggravating advocate, which delighted residents and incensed politicians. He later replaced Cecil B. Moore, another firebrand, and became City Councilman from the 5th District, the one Darrell Clarke, his former aide, represents today.

Street understood the army of Pine-Sol ladies doing battle with brooms, and he promised help.

When Street was president of City Council, he worked diligently with Ed Rendell to pass Rendell’s plans. Once he became mayor in 2000, though, he sold almost $300 million in city bonds to fund the nation’s most ambitious urban renewal program. His urban renewal wouldn’t be dubbed “Negro Renewal,” however, like the programs from the ’60s. Patricia Smith, the first director of the Neighborhood Transformation Initiative, stated emphatically, “We have learned from the failure of those programs and will absolutely not repeat their mistakes.”

NTI kicked off in 2002, and 13 years later, as the last of the money was being spent, Brian Abernathy, outgoing managing director of the City of Philadelphia and former executive director of the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, gave a full accounting of the project. Half the money had been spent in demolitions and the other half went to preservation, with the Divine Lorraine Hotel on North Broad Street and Bartram’s Garden in Southwest Philadelphia as examples. I remember the regular street cleanings and the towing of thousands of abandoned cars. Quality of life improved a little.

The problem is that urban renewal doesn’t lift folks out of poverty.

Most experts say what’s really needed is a good education system, and the city lost control of the school board to the state the year after Street took office. Today in America, in the average school district, white students score 1.5 to two grade levels higher than Black students.

The problem is that urban renewal doesn’t lift folks out of poverty. Most experts say what’s really needed is a good education system, and the city lost control of the school board to the state the year after Street took office.

Mark R. Shedd was a young Harvard-trained progressive reformer who believed in school integration. He became superintendent in 1967 but ran afoul of police commissioner Rizzo and was forced out of office when Rizzo became mayor. Before he left, Shedd testified at a Congressional hearing in September 1971: “I would like to get right to the point. … The urban schools of this country are dying. They are dying from financial strangulation.” Then he proposed that the federal government spend $12 billion to nationalize the 25 largest school districts. Otherwise, he said, “There won’t be, in the words of one famous American, any urban public-school systems left to kick around. … ”

Instead of nationalizing the schools, we created charter schools.

When John Street left office, the poverty rate was 24 percent.

Mayor Michael Nutter

2008 — 2016

“We’ve had a poverty rate of over 20 percent for 30 years. The problems in American cities such as Philadelphia really come down to lack of opportunity, literacy and skill sets,” explains Michael A. Nutter, the youngest of the ex-mayors. He sips a hot chocolate at the Ritz-Carlton on an overcast winter day and greets old friends while explaining complicated issues in simple bullet points, like the Columbia University professor he is now.

Nutter is polite but aloof, matter-of-fact about incendiary issues, focused more on the data points than the people behind the stories. Like Goode, he promised to run the city like a corporation — a $4 billion corporation with 23,000 employees, with City Council as board of directors and residents as shareholders. Like Green, he promised irreproachable integrity. Like Rendell, he was a booster of Center City. On the campaign trail, he ran against John Street’s record even though Street wasn’t in the race. It played well with white voters.

But his style didn’t resonate with African Americans, especially African American women — stalwart Democratic voters. It came across as cold and calculating. It’s what years of elite education can do. A St. Joe’s Prep alum, he was a year ahead of me at Penn’s Wharton School. The Daily Pennsylvanian once called him the “ultimate Penn candidate.” But his style can come across as elitist, arrogant and out of touch to Black voters. Sometimes on the campaign trail, Nutter would say, “I’m just an unemployed brother from West Philadelphia, trying to get a job.” He called this “keeping it real.” He garnered more white votes than any African American in the city ever had. In the primary, he performed best in the city’s eight whitest wards.

In November 2007, Michael Nutter was elected the 98th mayor of Philadelphia. His plan was a continuation of Rendell’s neoliberal policies.

His support of stop-and-frisk alienated him the most in the Black community — a stand he has never backed away from even as evidence on police brutality and mass incarceration has mounted. He continued to support it as Michael Bloomberg’s national political chairman, even as his candidate was forced to backpedal.

But it all became moot when, in September 2008, Lehman Brothers failed, the economy tanked, and all Nutter’s promises went down the drain as he was caught up in the Great Recession. Later, news media would begin to talk about a jobless recovery, and Nutter admitted that there wasn’t much a mayor could do about the market.

The city’s economy steadied by fits and starts, but poor workers were still trying to recover from the Great Recession. The poverty rate was 26 percent.

Epilogue

Poverty results from failed policies. We propped up the white middle class through union and government jobs at the expense of people of color (who were largely denied those jobs) and at the cost of the city’s financial stability.

The Brookings Institution’s Hamilton Project has created something called the Vitality Index, a measure of social and economic well-being for all the counties in the United States. Of the various factors it considers, three — poverty rate, unemployment rate and life expectancy — make up 41 percent of the total. A score above zero means the county is doing better than average; below zero, it’s doing worse. Philadelphia’s score is negative 1.52. Compare this with Montgomery (+1.39), Bucks (+1.27) and Chester (+1.62) counties. Even Delaware County is on the positive side (albeit barely) with a +.51. We’re worse than Baltimore (-1.41), Detroit’s Wayne County (-1.40), and New Orleans’s Orleans County (-1.50).

Once, when I was still at the Tribune, I interviewed a young, energetic state Representative named Chaka Fattah. His mother was the well-known Sister Falaka Fattah, who had started a lost boys’ residential program in West Philadelphia. He said, simply, that the best poverty program was a good job. Years later, President Clinton would say that, too.

A good job.

“The trouble is, we don’t have enough jobs. That’s what we need … and we need those jobs now like we need to breathe air,” Patrick Eiding said during a 2016 hearing of the state House of Representatives’ finance committee. Eiding is president of the Philadelphia Council of the AFL-CIO, which represents more than 150,000 working families. More than half of Philadelphia’s jobs are located in Center City or University City. Beyond that, Philadelphia is a jobs desert.

Wilson Goode, for one, doesn’t think Philadelphia can correct its poverty issue — at least, not alone. “It’s going to take all three levels of government to solve the problem,” Goode says, because the city can’t tax itself out of its woes. Goode believes that when a city reaches a certain level of poverty, the federal government should be able to declare a disaster in order to provide relief: “Poverty, like a hurricane, is a disaster.”

We have the Poverty Action Plan now. That’s what City Council President Clarke was talking about at the press conference in March when he said he was sure we could lift 100,000 Philadelphians out of poverty by 2024. I want to believe him, but that was before the economic disaster that is COVID-19 hit the city’s coffers. Kenney is desperately trying to figure out how to close a $750 million pandemic-related budget gap. He won’t be able to push the poverty rate downward before he leaves office. Instead, he’ll almost certainly become the sixth Democratic mayor in four decades to lose the fight to fix our poverty problem.

The struggle awaits our next mayor.

Published as “For 40 Years, Philly Mayors Have Been Promising to End Poverty. For 40 Years, I’ve Been Watching Them Fail.” in the September 2020 issue of Philadelphia magazine.

Philadelphia magazine is one of more than 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and economic mobility in the city. Read all our reporting here.