The Untold Tale of Cosmo DiNardo’s Descent Into Murder and Madness

The gruesome killing of four young men on a Bucks County farm made headlines around the world. For the first time, Cosmo DiNardo’s family opens up about his mental breakdown and his turn to evil.

According to an acquaintance, Cosmo DiNardo shared this photo on Snapchat in the weeks leading up to the disappearance of four young men in Bucks County.

In the middle of a murder rampage, Cosmo DiNardo had an appointment to see his psychiatrist.

So on the afternoon of July 6, 2017, the 20-year-old from Bucks County dutifully climbed into the front passenger seat of his mother’s SUV, and they headed south on I-95, toward West Philadelphia.

At the University of Pennsylvania, Christian Kohler specialized in evaluating and treating young people dealing with an initial onset of mental illness. He had been seeing Cosmo since November 2016 and was treating him for bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder and schizophrenia. He’d had him committed to a mental hospital — though Cosmo had been released — and was medicating him with anti-psychotic drugs.

For Cosmo and his mother, Sandra Affatato DiNardo, the previous year had been harrowing. Cosmo had been behaving violently, going in and out of psychiatric facilities, and Sandra had lived in fear of another storm — another violent psychotic episode in which Cosmo, amped up with manic superpower strength, would suddenly attack someone in the family.

But according to a lawsuit recently filed in Common Pleas Court, Kohler — who through a lawyer declined to comment for this story — seemed to believe Cosmo’s situation was improving. A month earlier, he’d declared that Cosmo’s bipolar disorder was in full remission, and he’d reduced his medications. That day in the office, according to the suit, he completely stopped Cosmo’s medications.

Neither he nor Sandra DiNardo had any clue how dangerous Cosmo had become — or what he had already done.

Just a day earlier, Cosmo had offered to sell 19-year-old Jimi Patrick $8,000 worth of marijuana. But after bringing Jimi to the DiNardos’ sprawling farm in New Hope, Cosmo shot him to death with a .22 rifle and buried the corpse in a grave that he dug with a backhoe.

And he was just getting started. Even as he sat in the waiting room that day at Penn, killing time before he saw Kohler, Cosmo used his iPad to google the “Soup Maker Cartel,” a Mexican drug syndicate known for making “soup” out of some 300 murder victims by dissolving their bodies in barrels of acid.

This was the frightening mind-set of the young man Kohler would see that day. But the psychiatrist seemed unaware that he was dealing with a time bomb. In his notes, Kohler wrote that his patient posed “no clear risk to self or others.” So Cosmo walked out of Kohler’s office and drove home with his mom.

The very next day, July 7th, Cosmo and his cousin, 20-year-old Sean Kratz, lured two more young men to the DiNardos’ farm, also under the pretense of selling them marijuana. But 19-year-old Dean Finocchiaro and 21-year-old Tom Meo, who brought along a friend, 22-year-old Mark Sturgis, were walking into ambushes. What happened next made international news.

Cosmo and his accomplice proceeded to shoot all three men, killing two of them instantly with a .357 handgun that Cosmo had stolen from his mother. When he ran out of ammo, Cosmo hopped on a backhoe and rolled over Meo, who was still alive and screaming, crushing him to death. Instead of dissolving the bodies in acid, however, Cosmo doused the three corpses in gasoline and set them on fire in an oil tank that had been converted into a “pig roaster.”

Then he went out for a cheesesteak.

“My son was supposed to be the mayor of this town. He was going places. Everybody loved him.”

That’s Antonio “Tony” DiNardo, Cosmo’s father, talking about his son. Tony’s a brawny guy with a long, Brando-esque aquiline nose and the callused hands of a cement contractor. When Tony showed up at the police station to bail his son out of jail in the summer of 2017, TV cameras captured him wearing a t-shirt, shorts and construction boots. When he shows up at his lawyer’s office in Center City on this day nearly two years later, Tony is dressed pretty much the same, except he’s wearing jeans instead of shorts.

Before his son’s murder rampage, Tony DiNardo was the patriarch of what, at least from the outside, appeared to be an all-American family. Tony and Sandra had founded and prospered their own concrete and construction business. Cosmo, who was named after Tony’s father, was the eldest of four good-looking kids with promising futures. In 2005, the DiNardos purchased their farm in New Hope, located some 20 miles north of their suburban home in Bensalem; it became a family vacation spot for activities that included deer hunting and riding ATVs.

There’s a frontier side to the DiNardos. All the family members know how to drive trucks and backhoes due to their construction business. (Sandra and Tony both have commercial driver’s licenses; Cosmo had a commercial driver’s license learning permit.) And all the DiNardos — including Sandra, who had a permit to carry her .357 — knew how to shoot.

In July 2017, investigators search the DiNardo family farm for Jimi Patrick, Dean Finocchiaro, Tom Meo and Mark Sturgis, who had all gone missing. Photograph via Associated Press

Tony and Sandra built all eight homes in their suburban development in Bensalem Township, including their own four-bedroom, three-bathroom house, with a backyard in-ground swimming pool. They also built more than 30 additional homes in the city and suburbs, as well as a dialysis clinic and the Bridge, a short-term residential center for adolescents in Philadelphia.

In addition, the DiNardos had a snow removal business. When a blizzard hit, the whole family was out plowing snow with trucks and backhoes. The DiNardos have spent a lifetime building what they say was a reputation for being honest, hardworking businesspeople. But now they’re internationally known as the parents who bred and allegedly enabled a serial killer. That’s why, for the first time, they want to tell their side of the story.

Inside the Center City office of her lawyer, George Bochetto, Sandra DiNardo looks like a woman who’s just survived a shipwreck. Her eyes are red and puffy because she cries a lot, especially when she talks about Cosmo. She’s wearing a cross around her neck and has long chestnut hair, big dark eyes and perfect olive skin. Underneath the ravages of guilt and grief, there’s the architecture of a classic Italian beauty — one who’ll tell you she tried everything she could to save her son, only it wasn’t enough.

“I don’t know if there’s help for mental illness,” she says. “I tried to get help, but there was no help out there.”

Before Cosmo became a killer, Tony and Sandra say, they saw him as a model son — a straight-A student and a dependable, hardworking employee in the family’s businesses. He graduated from Holy Ghost Prep and won a scholarship to Arcadia University; he talked of becoming an orthodontist. In part, they hold Cosmo’s psychiatrist, Christian Kohler, responsible for the tragic outcome, and they’ve filed medical malpractice cases against him and the University of Pennsylvania Health System.

In a complaint filed by attorney Jim Beasley Jr. in February with the Common Pleas Court, Sandra charges that the psychiatrist was “well aware of Cosmo’s complex and dangerous history of psychosis, suicidal/homicidal thoughts, grandiose speech and violent behavior.” But “despite this knowledge, Dr. Kohler grossly and negligently allowed Cosmo to stop taking his medication, lapse into remission, and kill four men.” An attorney representing the University of Pennsylvania Health System told this magazine that he “cannot comment on pending litigation.”

Other people, though, point the finger at the DiNardos themselves. In lawsuits filed in 2017 and 2018, the parents of Cosmo’s victims accused Tony and Sandra of functioning as enablers by providing their son with access to all the tools needed to wreak murderous mayhem, including the .357, the backhoe and the pig roaster.

The story of Cosmo DiNardo is about a young man’s frightening descent into madness and a world of suburban depravity. It’s also about a mother who insists she waged a doomed campaign to save her son from the ravages of severe mental illness, only to see her efforts end with the gruesome discovery of burnt bodies buried on the family farm.

Though some people remember Cosmo as having anger issues, other family friends and neighbors describe him as a polite and courteous young man who was always willing to help other people. “Cosmo DiNardo is the kind of kid who would always say hello, and he would grab your groceries out of your hand and walk you to your car,” a neighbor would write to the judge in Cosmo’s case.

“If my husband was digging in the yard, Cosmo would grab a shovel and dig alongside of him,” offered another family friend. “If he saw me shopping he would carry my packages inside for me. When it snowed, he would shovel my driveway.”

In junior high, Cosmo was the 130-pound captain of the Bucks County Bears — until his football career ended with several concussions and a neck injury. In January 2015, while he was a senior at Holy Ghost Prep, he was appointed to serve on Bensalem’s anti-drug-and-alcohol task force; he was reappointed in 2016. He also received an award from the township for his volunteer work in helping to rebuild a church.

Sandra and Cosmo DiNardo on prom night 2015. Photograph courtesy of the DiNardo family.

Sandra says Cosmo’s issues began sometime in 2015. He’d broken up with his girlfriend, and a plan to become a Navy SEAL hadn’t worked out. In February 2016, he was diagnosed with a “major depressive disorder.” He didn’t complete the second semester of his freshman year at Arcadia University.

That spring, his problems only grew worse. In May of 2016, Cosmo was involved in an ATV accident on the family farm in New Hope. He was pinned under the vehicle for hours; in addition to head injuries, he suffered compound leg fractures and wound up in a wheelchair, with a cast that ran from his hip to his toe. A month after his ATV accident, Sandra says, Cosmo began acting bizarrely. He stopped eating his mother’s cooking, saying she was trying to poison him. He also became physically aggressive.

In response, Cosmo’s doctors prescribed strong antidepressants, which eventually caused him to gain an alarming amount of weight. Once, his mother says, her five-foot-10, 160-pound son had a muscular physique, like his father, and was considered to be the “hottest boy in Bensalem.” But “He just blew up like a house,” Sandra says, eventually gaining a hundred pounds and sprouting “man boobs,” which only added to his depression.

That July, Sandra was driving Cosmo to Abington Memorial Hospital to get him to voluntarily admit himself. They never made it. They got into a fight over a cell phone, and Cosmo bit Sandra’s arm severely and gave her a black eye. On crutches because of the ATV accident, he limped out into traffic and attempted to jump into a woman’s car, claiming he was trying to escape a kidnapping. He was apprehended and wound up in the hospital in handcuffs.

“He felt his mother was a Russian spy and that his cast was bugged,” according to excerpts from medical records from the time. “Impression: Paranoid Schizophrenia.”

The episode was the first of three times over a five-month period in 2016 that Cosmo would be institutionalized for mental illness. As he moved in and out of mental health facilities, he became increasingly aggressive and dangerous. At Belmont Behavioral Hospital, where he stayed for three weeks, Cosmo threw a wheelchair at a female technician, struck a nurse several times, and had to be put in restraints. When he showed up at a Holy Ghost Prep open house in October, he was disorderly and eventually removed and banned from the campus. The following month, he was banned from Arcadia following verbal altercations there.

“The mother is overwhelmed trying to manage her son’s illness,” a psychologist wrote in July 2016. Excerpts of records from that time describe Cosmo’s parents as “extremely supportive” but their son’s mental condition as rapidly deteriorating. Cosmo was on and off his meds and having hallucinations; he was hearing voices as well as suffering from delusions. And he was really angry with his father because of Tony’s philandering.

“Cosmo talked about his father’s infidelities,” Cosmo’s personal psychologist, Geoffrey Wyckoff, wrote. “Said he hit the car of a woman who was with his father with a baseball bat. Father pushed him. They got in a fight.”

It was in November 2016 that Christian Kohler, the Penn psychiatrist, began to treat Cosmo. During his first visit, Kohler wrote that Cosmo “hunted after his dad with an AR-15 but decided ‘not to kill him’.” In December, Cosmo attacked his father inside the cab of a truck while Tony was driving, prompting him to be committed a third and final time. “Friday night he was angry at his dad for not coming home the night before,” Sandra told a social worker. “He ended up beating his dad up in the truck. … He came after me, and my husband hit him in the head with a brick. The cops were called because the neighbors saw us running.”

Cosmo, who was subsequently hospitalized for three weeks, had a “plan and intent to commit suicide” as well as “fleeting thoughts of homicide,” records state. He also threatened hospital staffers and was described as “delusional, grandiose, manic and hyper verbal.”

Sandra authorized Kohler to monitor her son’s time in the hospital. While being evaluated there, Cosmo told doctors, “If I had a gun, I’d kill them all.”

In her quest to save Cosmo, Sandra would ultimately seek help from at least 10 different psychiatrists and psychologists at eight different hospitals and mental health clinics. But she admits that in her desperation, she also looked elsewhere for an explanation of what was happening to her son.

The tree-lined cul-de-sac in Bensalem where the DiNardos live is a pleasant suburban setting. But like the DiNardo family, the street has secrets. According to a local legend that neighbors have told Sandra, the homes here were built over a Native American burial ground. Sandra worries that it might be true. She’ll tell you that for years, she’s heard screams in her basement. Her husband, a skeptic, says he thought his wife was delusional until he heard them, too.

Sandra also talks about how after Cosmo’s ATV accident, she and her son used to attend Mass every morning at 6:30 a.m. at St. Charles Borromeo Roman Catholic Church in Bensalem. Cosmo, who wore a cross around his neck, “always had his Bible with us,” his mother recalls. He used to decorate his room with statues of saints and crucifixes and would fall asleep at night with his Bible on his chest, trying to ward off evil.

As he was becoming more aggressive in the summer of 2016, Sandra says, Cosmo warned her that he was under spiritual attack and was hearing voices telling him to do violent things. She turned to the church for help, asking Father Charles Ravert, her parish priest, to perform a spiritual cleansing of her house, to exorcise any demons that might be lurking.

Sandra turned to the church for help, asking a priest to perform a spiritual cleansing on her house, to exorcise any demons.

“We started in the basement,” Sandra recalls. Like a scene out of a low-budget horror movie, the priest told her he “felt a horrible feeling at the fireplace, really bad,” she says. At the time, Ravert was “spreading incense, saying prayers, and doing the sign of the cross in every room.” As he walked upstairs and entered Sandra and Tony’s bedroom, the priest told Sandra he had an uneasy feeling.

According to Sandra, here’s what happened next: Ravert ran outside and vomited on the lawn. In a brief phone interview, the priest acknowledged his relationship with the DiNardos but declined to discuss the spiritual cleansing; the Archdiocese of Philadelphia, he said, frowned on publicly discussing such matters. When I sent an email to the priest, an Archdiocese spokesperson wrote back, saying, “Father Charles is not inclined to discuss the DiNardo family, nor will he provide further comment.”

Somewhere along the way, Cosmo, the onetime anti-drug crusader, began talking constantly to friends about selling drugs and guns. His lawyers caution that there is scant proof that any of the deals Cosmo talked about ever happened. But his condition continued to deteriorate.

As Christmas 2016 approached, Sandra DiNardo no longer recognized her son. Cosmo was taking all kinds of anti-psychotic drugs to control his behavior and having adverse reactions. When he wasn’t acting violent or bizarre, he would tremble and foam at the mouth. “His eyes just pierced right through me like there’s no emotion,” she recalls. “He was talking very vulgar.”

Cosmo’s private psychologist reported that the situation was dire. On December 19th, Geoffrey Wyckoff wrote that Cosmo, who was off his meds, “was making vile sexual comments to his mother” and telling “stories about selling drugs, cutting someone’s head off with a chain saw and feeding him to an alligator.”

“It’s hard to say whether Cosmo really believes these stories as he claims,” the doctor wrote, but he concluded that Cosmo was “clearly manic and delusional.”

That same day, Sandra drove Cosmo to Penn to see Kohler. During the visit, Cosmo was acting up again; he punched his mother, kicked an elevator, and wouldn’t stop cursing. Then, after he hit on a female receptionist, Cosmo stuck out his tongue and ran it down the glass window between him and the woman.

According to the lawsuit Sandra DiNardo filed against Kohler, the psychiatrist told Cosmo that if he didn’t behave, he would be kicked out of the office. Sandra, in disbelief, pleaded with Kohler for help.

“I was visibly shaking,” she recalls. She says she slammed her hands on the table and said, “Doctor, I can’t go home with him. He’s going to kill me.” She says she sat at his desk and refused to move. “I’m not leaving unless you help me,” she recalls saying. “I’m not gonna make it home alive.”

Kohler changed the mix of medications Cosmo was taking. When they got home, Sandra prayed the rosary all night and pleaded with God: “Please give me back my son.”

The next morning, after he took his new medications, Cosmo was peaceful, Sandra says. Instead of cursing, he said, “Good morning, Mama, how are you today?”

“It was a Christmas miracle,” Sandra says. “The old Cosmo was back.”

Despite this brief respite, there were plenty of signs that winter that Cosmo remained troubled and aggressive. Just two days after Christmas, he posted on his Facebook page: “I am a savage no explanation needed.” On January 20, 2017, the day before his 20th birthday, he twice wrote on Facebook, “Birthday sex anyone ?????” The following day, he posted, “Who wants to go out with me tonight for my birthday?” And then, “Who loves intercourse like me?”

In February, a witness spotted Cosmo getting into his family’s 2008 Cadillac with a shotgun and called Bensalem police. An officer eventually pulled Cosmo over and found him in possession of a Savage Arms 20-gauge shotgun — a felony under a state law prohibiting anyone who has been involuntarily committed for psychiatric care from possessing a firearm. Cosmo was arraigned but never sent to jail, and a judge eventually dismissed the charge due to faulty paperwork.

Later that month, Cosmo was involved in a fight at Temple University during which he was cut on the face with a bottle. According to the family’s complaint, Kohler noted that Cosmo was “cut on the chin and sustained [a] shiner on right eye” but concluded that he wasn’t a risk to himself or others.

During a March 16th visit, per the complaint, Kohler noted that Cosmo had been off his medication for two days and had worsened, but by late March, the doctor believed that Cosmo’s bipolar disorder was in remission.

As of April, Kohler felt that Cosmo continued to make progress. He noted that his patient was taking his meds every other day instead of every day. While observing, according to the DiNardos’ suit, that Cosmo was experiencing “low hypomanic/elated mood,” Kohler reduced his meds. The following month, Kohler wrote in a letter, “Cosmo has responded well to treatment and his symptoms are currently in remission.” And in June, Kohler, still observing “improved-low hypomanic/elated mood,” further reduced Cosmo’s meds and concluded, per the complaint, that his “bipolar disorder was in full remission.”

According to Sandra, Kohler advised her and her husband to give Cosmo more space, an assessment Cosmo agreed with. “I want to start hanging out with the kids,” he told his mother. “I want to start to have a life.”

Old friends had shunned him. That winter, Sandra DiNardo emailed Kohler to say that her son had posted a message on Facebook: “It’s official I have no friends.” The message “broke my heart,” Sandra told the doctor. Cosmo needed a friend.

Tragically, so did Sean Kratz. Sean’s mother, Vanessa Amodei, called Sandra and asked if it would be all right if Sean, who was from Northeast Philly and lived in Ambler, started hanging out with Cosmo. The two young men, who were the same age, were related; Cosmo’s father, Tony, and Vanessa were first cousins, but their sons hadn’t seen each other in years.

Sean, however, was another troubled young man. He was investigated in an attempted murder in Philadelphia, a shooting that had left another man in a wheelchair. Sean, scrawny, with a scruffy goatee, walked with a limp because he was still recovering from an unsolved drive-by attack, believed to be retaliatory, in which he was shot 19 times.

Sandra DiNardo says she didn’t know about any of that — or that Sean had been involuntarily committed by his mother for eight days the previous September for “violent tendencies and threats.” According to a newspaper account, prosecutors have alleged in court records that in September of 2016, Sean flashed a gun at his nine-year-old brother and threatened to “blow his brains out”; he also threatened to kill his sister. Sean’s mother committed him to Friends Hospital in the Northeast.

When Cosmo and Sean started hanging out together, their mothers naively hoped they would keep each other out of trouble. In early July of 2017, Sandra texted Vanessa, lamenting about her son. “Yes I just feel how his whole life has changed all from hitting his head and no one catching it,” she wrote. “It breaks my heart and people are so mean. No one wants to hang out with him. At least no one good.”

“That’s so sad, it really is,” Vanessa wrote back. “Hopefully he gets better over time. Him and Sean would be good together in that sense. Neither one knows anybody worth anything. They should stick together and stay away from the trash.”

“True,” Sandra wrote. “We just need to make sure they don’t get in trouble together because Cosmo has no more sense of fear or what’s right or wrong.”

Jimi Taro Patrick, 19, of Newtown Township, had been a classmate of Cosmo’s at Holy Ghost Prep, where Cosmo was a year ahead of him. Years earlier, Jimi had told his grandmother, Sharon Patrick, who raised him, that Cosmo taught him how to make money by selling sneakers. Cosmo would pay kids to stand in line at shoe stores to buy the latest hot sneakers; Cosmo would then sell the sneakers online for a profit. According to what Jimi’s friends told police, Jimi subsequently graduated to selling weed.

Jimi had an innocent face, but he’d been kicked out of high school. Photos found on his phone showed guns and drugs, and there was also a video of Jimi snorting a white substance.

On the July night that Jimi disappeared, he told his grandmother he was going out to get something to eat and wouldn’t be long. At 2 a.m., when he wasn’t back yet, his grandmother texted: “Jimi, where are you?”

Two nights later — the day after his visit with Kohler — Cosmo picked up Sean Kratz in his truck. They purchased three five-gallon gas cans at Home Depot and 13.5 gallons of gas at APlus. Cosmo was in the habit of buying and storing gas for his ATVs. But he would also come up with a more sinister use for it.

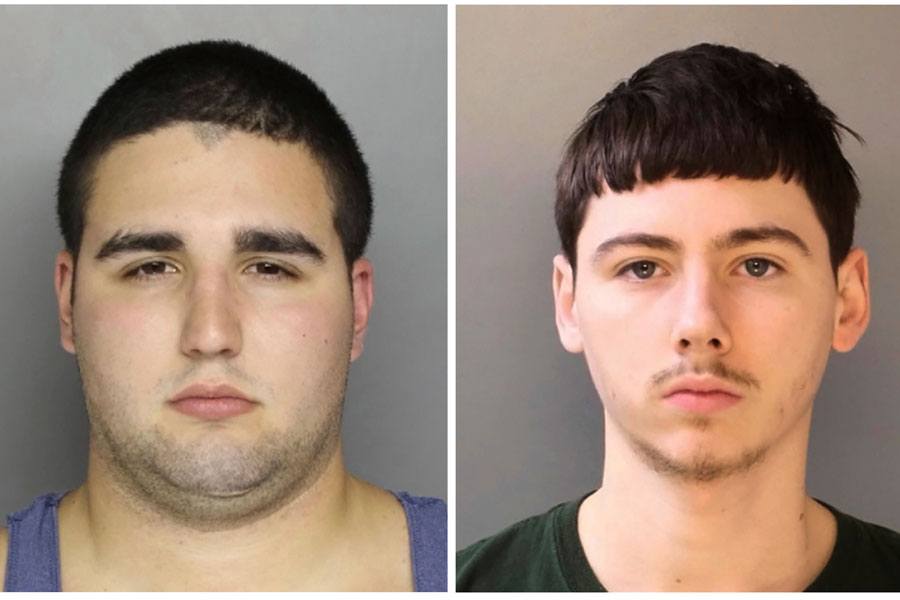

Cosmo DiNardo (left) and his cousin, Sean Kratz (right). Photographs via Associated Press

Cosmo and Sean then picked up Dean Finocchiaro, supposedly to sell him a quarter pound of marijuana, and drove to the DiNardos’ New Hope farm. A friend of Dean’s told police that Dean had tried to buy a TEC9 from Cosmo, but when the gun misfired, Dean backed out of the deal.

According to text messages found on his phone, Dean was another troubled young man. Dean’s friends told the cops that Dean bought and sold drugs. He also struggled with depression and had checked into a mental health facility as an inpatient.

Family members were long concerned about Dean’s use of drugs. A few years earlier, Dean’s brother texted him to say that “people I went to high school [with] that were like you are all either dead from overdoses or drug addicts. You gotta start caring.”

The same day that they met up with Dean Finocchiaro, Cosmo and Sean picked up Tom Meo and his best friend, Mark Sturgis, and drove back to the farm. Tom had dropped out of East Stroudsburg University and was working a construction job and a part-time gig at a gas station when he decided to meet up with Cosmo. Friends told police that Tom sold large quantities of marijuana. When he went to see Cosmo, Tom brought along Mark, described by his mother as a “teddy bear” who looked and clowned around like his favorite actor, Jack Black.

That night, after all three victims had been killed, Cosmo and Sean showed up at the DiNardo house, seemingly in good spirits. They told Sandra they’d been out “quadding,” riding ATVs. Cosmo went to his bedroom for the night; Sandra let Sean sleep in another room.

Later, the two moms, Sandra and Vanessa, exchanged texts about their sons.

“Well they sounded like they were having fun,” Sandra wrote.

“I hope they both use their positives to cancel out the negatives,” Vanessa texted back. “LOL. I’m sure you do too. And I think they will.”

“And thank u,” Sandra replied. “Cosmo really needed a friend.”

As news reports quickly spread about four young men missing in Bucks County, pings off of cell towers led police to Dean Finocchiaro’s phone, which was still on and found on the DiNardos’ farm. The police also discovered Tom Meo’s abandoned car parked on neighboring property. As the media gaze mounted, hundreds of volunteers, police officers and FBI agents, as well as cadaver dogs and a helicopter, searched the property. After several days, authorities finally unearthed a grave site containing the remains of Dean Finocchiaro, Tom Meo and Mark Sturgis.

When Sandra and Tony DiNardo repeatedly asked their son why police were searching their farm, he kept saying he had no idea. After the police arrested Cosmo, his parents at first refused to believe their son had killed any young men. But he finally came clean.

Sandra collapsed against a wall, crying; Tony screamed, “Why, why, why?”

People who knew the old Cosmo grappled with his transformation into a killer. “I watched him change and struggle with his mental health,” Chris Hellmuth wrote in a Facebook post after the murders, identifying himself as a close friend of Cosmo’s since the fourth grade. “The Cosmo I knew for over 10 years would never be capable of anything like this, but his current mental state is not one of a rational human being.”

Stephen Haffner, who knew Cosmo for six years, told the police that he could tell when his friend was off his meds. Cosmo had been a different person since the ATV accident, Haffner told the cops; he used to be “the sweetest kid.”

During a lengthy videotaped confession, DiNardo told police that he killed Jimi Patrick, his first victim, in self-defense because he saw a Glock in Jimi’s backpack.

“I knew he was gonna whack me,” Cosmo said, so “I whacked him first” with the .22 rifle. “Put two in the back of his head.”

The rifle, police said, was reported stolen a year or two earlier from North Carolina. When police interviewed Cosmo’s parents, the DiNardos said they had no idea how either it or a shotgun found at the barn had ended up in Cosmo’s hands.

Cosmo told police that Sean shot Dean in the back of the head several times with Sandra’s .357; after Dean was down, Cosmo finished the job by shooting him one or two more times in the back of the head. “His head was split the hell open,” Cosmo told the cops. “Half his brain was in the barn.”

Cosmo shot Tom Meo, his third victim, in the spine, paralyzing him. Mark Sturgis, the fourth and last victim, tried to run away, but Cosmo shot him, too, and then ran out of ammo. Tom was still screaming. “I can’t feel my legs, I can’t feel my legs,” Cosmo quoted the victim as saying. So, Cosmo told the cops, he hopped on the backhoe and ran over Tom, crushing him.

“Dead instantly,” Cosmo told the police.

In his confession, Cosmo said he used the backhoe to pick up the bodies and dump them in the pig roaster. Then Cosmo doused them with gasoline and lit them on fire. While the corpses were still smoldering, Cosmo and Sean went out for cheesesteaks at Steve’s Prince of Steaks. But Cosmo had an upset stomach.

“I didn’t eat mine,” he told the cops about his cheesesteak. “I just did something so gruesome. I didn’t have the appetite.”

Cosmo told the cops that the day after the triple murder, he and Sean returned to the farm to finish the job. Cosmo used the backhoe to dig a 12-foot-deep common grave for the three victims.

During his confession, Cosmo, who was off his meds and manic, was alternately giggling and making small talk with cops and lawyers. He finally broke down and cried. “I don’t know why I did this shit, man,” he said. “I threw my life away for nothing. My life is done, for nothing.”

When his chilling confession was over, Cosmo said, “I am just a happy-go-lucky guy. This is why it’s so fucked up.” His defense attorney, in an attempt to comfort him, responded, “Ninety percent of Cos is a fun-loving good son, and you’ve got this dark side that fucking eats you up and you kill people.”

In the aftermath of the murders, one of the people who called Sandra to offer help was Thomas Klebold. He’s the father of Dylan Klebold, who, together with Eric Harris, killed 13 people and wounded 21 others in the massacre at Columbine High School in 1999. Sandra was appreciative of the offer but distressed about the infamous company Cosmo was now in. “My son wasn’t this horrible animal that everybody says he was,” she argues. “He lost his life a year before those kids. He’s a prisoner in his own brain. He’s lost forever.”

In May of 2018, Cosmo pleaded guilty to four counts of first-degree murder and related charges that included robbery, conspiracy and abuse of a corpse. To escape the death penalty, he had agreed to show police where he’d buried Jimi Patrick’s body on the farm, a half mile from the common grave where he’d buried the other three victims. The judge who sentenced Cosmo to four consecutive life terms noted that during his confession, Cosmo had shown that to him, “Human lives are disposable. They have no value.”

The night Cosmo killed the three men, did he intend to murder one more victim? Earlier that evening, Tony DiNardo had pulled into the driveway at the farm, according to police records. But he quickly turned around and left. Tony, according to the police, had another woman with him in his truck and didn’t want Cosmo to catch them together.

Tony DiNardo leaves a Bucks County government building on July 13, 2017. Photograph by Matt Rourke/Associated Press

Police records show that Cosmo called his father three times on his cell phone that night. “Come alone,” Cosmo told his father.

Despite all they’ve been through, Cosmo’s parents present a united front during an interview as they talk about all the doctors and hospitals that couldn’t help Cosmo.

“I want people to know that the system failed my son,” Tony says. “They make these medicines that are supposed to help kids. And they don’t help kids; they make them worse.”

Because her family construction business was located in North Philadelphia, where there had been several robbery/ murders, Sandra DiNardo says, she’s had a permit to carry her .357 magnum since 2005. She kept the gun in a hidden lockbox in her dining room china closet. After the police showed up at her door looking for Cosmo, “I open my china closet, and my box is gone,” she remembers.

The parents insist that after Cosmo was committed for the first time, in July 2016, they removed all guns from their home except for Sandra’s .357. “I don’t know how [Cosmo] knew my gun was there,” she says.

The day of the triple murder, Sandra says that Sean distracted her while Cosmo went inside the house and stole the lockbox containing the .357.

Today, Tony grapples with many emotions. “He was my best friend,” he says about the Cosmo who used to be. “He was so respectful. He was with me all the time. … He could run a backhoe, a bulldozer; he could drive any kind of a truck.”

After Cosmo went to jail, his bedroom at home stayed empty for months. “I can’t go into Cosmo’s room without bawling my eyes out,” Sandra says. And when the Christmas holiday rolled around, “I couldn’t make fried cod.” It was Cosmo’s favorite.

Like the parents of the victims, Cosmo’s parents mourn the loss of a son. “I cry every day,” Tony says. About the victims’ families, he says, “I know they have a hole in their heart, but so do we. Our kid is in jail for life.”

People, Sandra says, think “we’re monsters.”

Last May, after he went off his meds again, Cosmo became manic and got into a fight with his prison roommate. He was placed in solitary confinement, where he made the mistake of covering the only window with a towel. When he didn’t respond to commands to take down the towel, a team of corrections officers stormed his cell, and a fight ensued. Cosmo wound up in the prison hospital with a broken nose, an injured jaw, and a probable concussion.

Last November, Sean Kratz, Cosmo’s accomplice in the murder spree, went on trial in Doylestown. The courtroom was packed with reporters as well as family members of the four victims.

A jury found Kratz guilty of first-degree murder in the death of Finocchiaro and of voluntary manslaughter in the deaths of Meo and Sturgis. A judge sentenced him to life in prison for Finocchiaro’s murder and an additional 18 to 36 years for the other two slayings. Chuck Peruto, Kratz’s defense attorney, has said they’ll file an appeal.

For Tony and Sandra DiNardo, the Kratz trial was traumatic, not only because they had to relive the tragedy, but also because they were both called to the stand as witnesses.

Peruto asked Tony whether Cosmo had phoned him on the night he killed three young men.

Cosmo did call, Tony said, and demanded to meet his father. Peruto asked if Cosmo was angry when he called.

“He was mad. I could tell he was angry,” Tony said. Then he explained why.

“He [Cosmo] asked if I was with a certain person and I said yes,” Tony said, referring to his mistress.

But later that night, according to Tony, “He [Cosmo] called me again and said, ‘You don’t have to go, it’s okay.’ I was glad.”

Next, Peruto called Sandra to the stand and asked if she was afraid of her son.

“Objection,” the prosecutor said. “Sustained,” said the judge.

On cross-examination, the prosecutor asked Sandra if, when she saw Sean at her house the night of the triple murder, he “appeared to be in fear.”

“No,” she said.

Was he crying? the prosecutor asked.

“No,” she said. “We were talking. He seemed fine.”

But at this moment, Sandra was not fine. As she left the courtroom, she had to pass four rows of seats reserved for the victims’ families — the same four families who, represented by legal heavyweights such as Tom Kline and Robert Mongeluzzi, are suing the DiNardos in civil court for damages in four wrongful death cases.

In the middle of a murder trial, what happened next was a brief, unusual moment of reconciliation.

As she passed the mothers of Dean Finocchiaro and Mark Sturgis and Jimi Patrick’s grandmother, Sandra started crying and managed to utter, “I’m so sorry.”

“Thank you,” Dean’s mother said.

Jimi’s grandmother was silent but gave a wink and a thumbs-up as Sandra rushed out of the courtroom in tears.