Desperate for High-Paying Wall Street Jobs, Penn Students Try Buying Their Way Into the Right Classes

Out-of-control corporate recruiting — and a new black market — transforms our favorite Ivy League university.

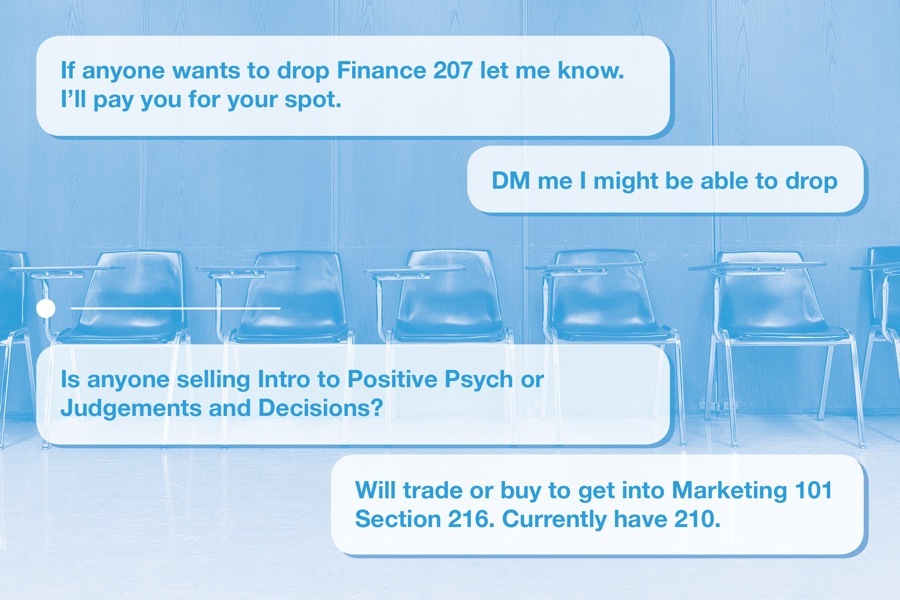

Some Penn students — seeking a leg up in the hunt for lucrative finance internships — have tried to buy their way into popular classes. Photo courtesy of University of Pennsylvania.

A few weeks ago, Matthew Current, an undergrad at Wharton, woke up at 6 a.m. with a plan. He was trying to enroll in Finance 207, a course called Corporate Valuation. He’d signed up for it back in November as his first choice, but because Penn’s registration system gives priority to upperclassmen and he was only a sophomore, when he went to look at his schedule, he came up empty. Corporate Valuation was full.

So Current made other arrangements. He’d noticed that a number of students had been posting in Penn student group chats saying they’d be willing to pay their way into courses they hadn’t been able to get into. There was a simple workaround: These students would offer money to entice another student to drop the class, then swoop in through the online registration portal to take the newly free seat. The going rate looked to be about $50 to $60 for a class.

Current sent a message to a group chat of Wharton sophomores. Not long after, he got a response: A girl was on the fence about taking the class in the first place; sure, she’d be willing to drop it for a price. Current offered her $60 and strategized: He’d call her at 6 a.m. to signal that she should drop out, figuring no one else could possibly be trawling for course openings at that hour.

“People might see this and think it’s crazy that people would buy or sell a spot in a class,” Current told me recently. Tuition at Penn, after all, runs more than $55,000 a year. But for him and other Penn kids playing in this budding black market, there’s a simple financial calculation involved: Getting into just the right class can significantly increase your chances of landing just the right financial-world internship — an internship that often feeds into a full-time post-grad job. So what’s a few bucks now in a career that might ultimately bring in tens — maybe even hundreds — of millions of dollars?

Five years ago, sophomores like Current might not have been so desperate. Back then, finance companies hired for their all-important junior-year summer internships just a few months ahead of time. But recently, in an attempt to scoop up the best students before anyone else, companies have moved up the timeline. It’s now standard practice for finance firms to recruit sophomores like Current — who has only completed three semesters of college and hasn’t even declared a major — for those same junior-year summer internships a full 18 months in advance.

A lot can seem to hinge on one course. Corporate Valuation, Current said, was “hands-on, applicable experience” that would help him in his interviews. He needed to perform in those interviews in order to land the best internship; he needed the internship in order to potentially receive a full-time job offer at the end of the summer. Correction: next summer.

“If you think about the future,” Current said, performing an opportunity-cost analysis mid-sentence, “the potential to earn money from that internship, or the value of experience you’d get, would be worth the $40 or $50 you’d pay for the class.” And with interviews around the corner, that experience couldn’t wait until he was a junior or senior with priority course registration. He needed it now.

As it happened, Current’s scheme to buy his way into Corporate Valuation didn’t quite work as planned. He was foiled by the course registration system. His co-conspirator did indeed drop the class, but a spot never opened up. (Current now thinks he failed to account for a wait-list.) But while he came up empty, other students say they know people who have succeeded.

“This is very common,” says junior Valentina Losada, another vet of the corporate recruiting wars. “It’s not even seen as something bad.”

According to Career Services at Penn, finance is the most popular job for graduates, with roughly 30 percent of the 2019 class working in the industry. The year before, the median starting salary for Penn grads working in finance was $85,000.

So you can imagine why, to put this in economic terms, demand for finance jobs is high. Supply, meanwhile, is low. The result is that big banks — J.P. Morgan, Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley — have a built-in advantage over the students. “We’re pretty dispensable,” says Valentina Escudero, a Penn junior who has been through the recruiting process. “If we don’t take this job, they can offer it to anyone else.”

Banks are aware of this, too. While the companies used to have a symbiotic relationship with Penn — the banks got access to the school’s finance whiz kids; the school got to brag about its whiz kids going to work at the biggest banks on earth — the tradeoff was that the banks had to cooperate with Penn’s rules about how and when to hire students.

But lately, the firms have realized they don’t need the university anymore; they can conduct phone and Skype interviews, then bring candidates to New York City for the final round. When deciding whether to recruit on campus at Penn or bypass the school and face no institutional regulation, guess which option the banks have chosen?

Having granted themselves free rein, many companies are now acting like monopolistic bullies. They move the recruiting cycles ever earlier in a race to reach job applicants first. (Shout-out to the free market!) They don’t give students time to consider other internships, sometimes requiring job commitments just one or two days after the initial offer. Escudero says she’s had friends who received offers only to be told they had to give their answer on the spot — take it or leave it. “It’s a form of psychological warfare, to be honest, to put someone in that position,” she says.

The status quo got so bad last year that a group of nine business-school deans, including Geoffrey Garrett of Wharton, sent a letter to 100 different financial recruiters, begging them to stop the recruiting madness. The letter tried to caution banks that sophomores were in no position to be recruited. First off, the schools argued, many of these students were too young to know if they actually wanted to work in finance. More importantly, the schools suggested, banks have no good way to evaluate talent when they’re interviewing students so early in their academic careers. Two of the largest banks, J.P. Morgan and Goldman Sachs, agreed to cut back, but hardly anyone else budged.

If you’re reading this without much sympathy for students competing for jobs that will pay them $85,000 — or nearly $25,000 more than the median American household income — right out of college, well, fair enough. But put yourself in their shoes for a moment. The student body at Penn is, in many ways, already conditioned to treat everything like a zero-sum game. In many Wharton classes, grading is on a curve, meaning students compete directly against their peers. Meanwhile, the most “desirable” extracurriculars are often finance and consulting “clubs” (heavy on the air quotes there) that require multi-step interviews nearly as rigorous as those of the banks. And of course, any internship spot that goes to someone else means there’s one less spot available for you.

It is, in short, not exactly an environment that breeds the idyllic college scene of bookish students who spend the day reading Sartre in the quad. Many students say the system creates a culture of hyper-competition that’s just plain unpleasant. “It’s almost impossible to balance staying involved and making sure you’re staying healthy,” says Wharton sophomore Jordan Bomba. “Applying to these internships and jobs 100 percent cuts away from that.”

“The stress is absolutely tremendous” and can even pit friends against each other, says Valentina Losada, who as president of the Wharton Latino club has advised a number of students during recruiting. “You feel like you’re competing against each other for the same two positions,” she says. “People stop talking to each other.”

The pressure also produces some peculiar unintended consequences, like the underground course-swap marketplace. Both Losada and Bomba say they have friends who have successfully bought or sold classes. (Current, the Wharton sophomore who tried to buy his way into Corporate Valuation, wasn’t one of them, though it’s worth noting that in the end, he got into the class, albeit through a more conventional route: off the wait-list.)

The black market for Penn courses mainly takes place over class-wide group chats. Illustration by Jamie Leary.

The important point here isn’t whether a student ultimately succeeds at buying into a course. The indictment comes from the fact that students are being compelled to try this in the first place. An article in the student newspaper, the Daily Pennsylvanian, recently decried the course-swap practice, but administration officials say they had no idea this was going on. A Wharton administrator forwarded my questions to a spokesperson, who said the school had “no information” on the subject. Neither did Barbara Hewitt, director of Career Services at Penn.

Hewitt does, however, have plenty of information about the cutthroat recruiting behavior. The worst and earliest offenders, she says, are “not getting students who have a firm idea of what they want to do with their careers.” There’s little Penn can do, now that so much recruiting — particularly among finance companies — happens independently of the school. “Companies will do what they want to,” she says.

And it’s not just financial firms. According to Losada, consulting firms get in on the action, too. She was first recruited by McKinsey for a diversity leadership summer internship program during the first semester of her freshman year. When she found out about the opportunity, she had to wait to apply: She didn’t even have a GPA yet. “That was way, way, too soon,” she says.

Still, it was an opportunity she didn’t feel she could pass up. And so she applied, eventually getting hired. In retrospect, the whole process seems kind of absurd. “Of course I wasn’t that prepared,” she says. “I didn’t know anything. I didn’t know what consulting was when applying.”

Short of a mass student revolt, there’s little reason to expect anything is going to change. “Companies break these rules without any consequences whatsoever because of course people are not going to stop applying,” Losada says.

There could, however, be another way forward. If the banks keep recruiting younger students, you figure they’ll eventually hire an intern class that underperforms. And if we know anything about Wall Street, it’s that left to its own devices, it will keep competing against itself and barreling forward until one day, it drives headfirst into a crash.