At Philly Court Hearing, a Wrenching Preview of Fight Over Safe Injection Sites

Safehouse made a moral argument that the opioid crisis compels a response. The federal government suggested morals don’t matter: The law is the law.

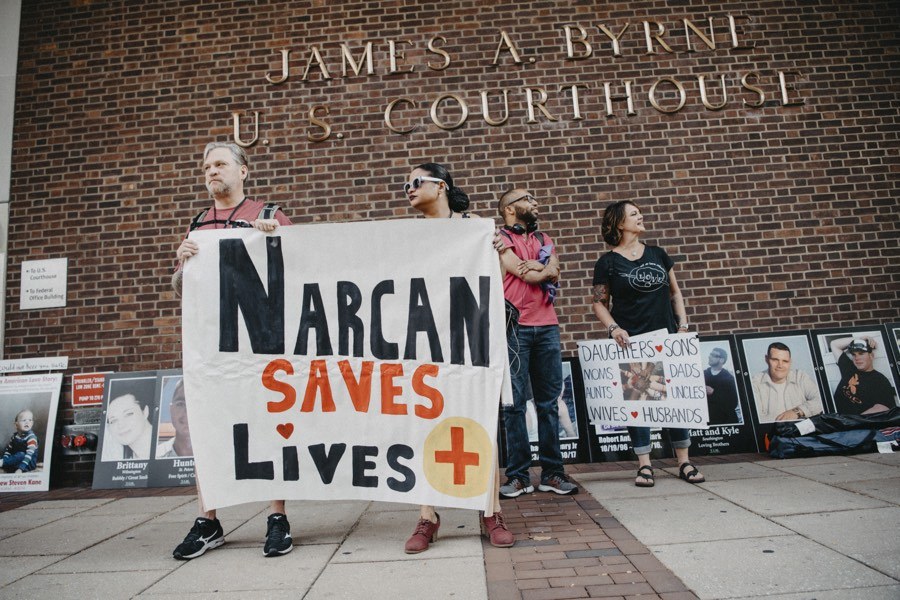

People demonstrate in support of safe injection sites outside the federal courthouse in Philadelphia. Photo by Holden Blanco.

Jose Benitez was rattling off statistics from memory under cross-examination from U.S. Attorney Bill McSwain. 15,000 people served last year at Prevention Point, the city-sanctioned nonprofit needle-exchange of which he’s the executive director. 100,000 yearly interactions. 80 beds for the homeless. 120 staff. 200 volunteers. 3.9 million syringes exchanged last year. 6,000 opioid overdose trainings. 500 overdoses reversed by Prevention Point. And still, 1,1100 overdose deaths citywide. 200 of them in Prevention Point’s ZIP code.

Then Benitez shared the most critical statistic of all: “Minutes are everything in overdose reversals.”

The point Benitez was making, at this hearing in federal court that will eventually determine whether the nation’s first-ever safe injection site is legally allowed to open in Philadelphia, was clear: Despite all those trainings, despite all that staff, despite all those lives saved — and they were, Benitez insisted, lives saved — people still are dying at an alarming rate. Which was precisely why a supervised injection site like Safehouse was not just a medical necessity, but a moral imperative.

This was just one of the arguments made at Monday’s nine-hour hearing in the case of U.S. v. Safehouse, the federal government’s lawsuit against Benitez and the nonprofit he founded in 2018. The purpose of the hearing was, Judge Gerald McHugh explained, simply to gather information on what Safehouse intends to do. But even at the preliminary hearing, the early contours of the battlefield started to become clear.

Laws Versus Ethics

For the government, the point, as it wrote in its original complaint against Safehouse, could be rather simply distilled: “It does not matter that Safehouse claims good intentions in fighting the opioid epidemic. What matters is that Congress has already determined that Safehouse’s conduct is prohibited by federal law.” The statute in question is the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, which states that “it shall be unlawful to knowingly open … or maintain any place, whether … for the purpose of manufacturing, distributing, or using any controlled substance.” (Safehouse argues that law doesn’t apply to a medical facility like itself.)

At the beginning of the proceedings, Judge McHugh, an Obama appointee, made what could end up being an ominous statement for Safehouse: “My job as a judge is to apply a statute.” Later, when Benitez demurred rather than answer a McSwain question about whether people in a safe injection facility would be breaking drug-use laws, McHugh chimed in: “I think it’s self-evident it would be violating the law and the witness has conceded that.” Another ominous statement.

But at the hearing, the intricacies and interpretations of the law were largely shelved in favor of bigger-picture questions. Safehouse’s first witness, Jeanmarie Perrone, a toxicology expert and an emergency medicine physician at Penn, explained with clinical candor the path of an overdose: A person may stop breathing within one minute of injecting heroin or fentanyl. Four minutes later, they could be braindead. She told the story of how she once sprinted along a subway platform to reach a man who was overdosing on the floor of the El. She’d been the only one to have Narcan, the overdose-reversal drug, on hand. “We can do better than having a group of people on the floor of the subway resuscitating a 25-year-old from a fatal overdose,” she said.

Later, Benitez told stories of other sprints — the ones his staff at Prevention Point make daily, in an attempt to reverse the tide of overdoses in the blocks surrounding their Kensington office. Sometimes they get there in time. Sometimes it’s too late. Minutes are everything in overdose reversals.

“Everything Is Exactly the Same”

The central thrust of Safehouse’s argument on Monday was that supervised injection isn’t all that different from what Prevention Point — which has been operating as a needle exchange with city approval ever since then-Mayor Ed Rendell signed an executive order authorizing it in 1992 — is doing now. One of the attorneys, Ilana Eisenstein, used a visual aid to make her point, projecting an image of a safe injection site in Vancouver onto a courtroom screen. On the left was a curved desk that looked like a control center; on the right was a row of chairs and semi-private stalls in front of mirrors.

Eistenstein asked Benitez how exactly Safehouse would work. Benitez explained how people would register at the door and provide demographic information such as their ZIP code, how there would be a medical evaluation, how the medical staff at the desk would pass out clean syringes, just as they do now at Prevention Point. He explained how the medical staff might offer medical treatment to those suffering from withdrawal with drugs like Suboxone, just as they do now at Prevention Point.

Then Eistenstein walked up to the screen, pointing at the desk on the left half of the photo. “So up to this point,” she asked, “everything is exactly the same?”

“Yes.”

What comes next is the source of legal contention: In Vancouver, as they would at Safehouse, drug users make their way to the stalls on the right, sit down and inject under medical supervision. At Prevention Point, they decamp to the streets, away from watchful eyes.

While the government mostly stuck to its letter-of-the-law legal onslaught, it occasionally waded into medical arguments — with little success. McSwain began his cross-examination of Benitez with a riff on selection of the name “Safehouse,” musing that couldn’t the name itself possibly entice a first-time user of heroin into thinking a dangerous drug was suddenly safe? Members of the audience audibly laughed. One person muttered, “Christ.” Benitez did not think so.

Later, McSwain challenged Benitez’s assertion that Prevention Point had saved 500 lives last year. What if someone, McSwain wondered aloud — jumping headfirst down a Mount-Everest-grade slippery slope — had been revived from an overdose only to go back to using the next day, and then die? “So you’re saying you saved a life, when in fact someone just died,” McSwain said. “You don’t say now it’s 499, not 500.”

“Neither do emergency rooms,” Benitez shot back.

These diversions were mostly short-lived. McSwain would soon return to the main point: that safe injection sites are illegal; that, even if, as Benitez argued, local, state, and federal legislatures have all abdicated their duties in the face of a crisis, it doesn’t matter. The law is the law.

It was hard to tell which way Judge McHugh was leaning. To decide in favor of Safehouse would be unprecedented. The critical moment will likely come in September, when the legal justifications will be presented at oral arguments. Despite all the testimony about the would-be medical benefits of Safehouse, the legal battle would seem to be the only one that truly matters. As Judge McHugh himself said at the beginning of the hearing: His job is to rule on a statute.

But for a few moments on Monday, as Benitez sat at the witness stand, with the tall figure of Bill McSwain before him and an American flag draped behind him, those legal arguments didn’t really matter. Benitez’s appeal was a humanitarian one.

“This is an emergency,” he said, rattling off more figures. “Eleven-hundred people died this year. Twelve-hundred the year before that. Nine hundred the year before that. Six hundred the year before that. This is an emergency.”