After 4 Suicides in 11 Months, a High School Searches for Answers

Students, parents, and community members at top-ranked Downingtown East in Chester County are trying to fathom the causes – and push for solutions.

Rachel Rondinelli stands beside her mother, Beth, while holding a photo of her sister, Rose (pictured on the left), a Downingtown East student who died by suicide in September. | Photo by Claire Sasko

For confidential support if you are having thoughts of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or text to 741-741. Learn about the warning signs of suicide at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Four suicides in 11 months.

Students at Downingtown East High School in Chester County — a wealthy, highly rated Pennsylvania institution with more than 1,700 students — are uttering those words over and over again, as if they can’t quite bring themselves to believe them. Since February 2018, they’ve seen four of their classmates — two current students and two recent alums— die by suicide.

Students, parents, and community members are distraught and desperate for answers. After the most recent death — a 15-year-old sophomore on January 7th — more than 7,500 people signed an online petition to raise mental health awareness at the school. Questions hang in the air over the surrounding suburban neighborhoods: Why does this keep happening, and how can we stop it?

Last week, I attended a Downingtown Area School District board meeting, where nearly 20 community members (far more than usual, attendees said) stood before a microphone and a packed room to express, at times through tears, their anguish and frustration to school administrators about the situation at East, from which I graduated several years ago.

Staff raised and lowered the mic accordingly as teens and parents formed a long queue to speak at the meeting, which lasted two and a half hours. Some students blamed weak relationships with school counselors, with whom they didn’t feel comfortable opening up. Others, including parents, lamented that students face too much academic pressure. In a particularly emotional moment, a young girl wearing a T-shirt and jeans pleaded in a shaky voice, “My peers are so sad … don’t let the issue drop. Please take care of us. We are so young.”

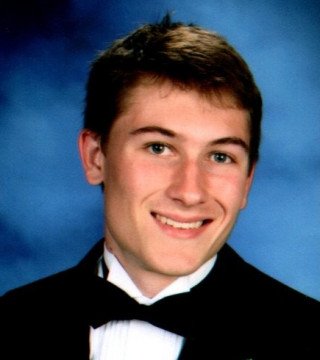

Rose Rondinelli

Also among those who spoke was 18-year-old Rachel Rondinelli, a recent East graduate. The evening before the school board meeting, Rondinelli posted an hourlong Instagram Live video, which she said more than 700 people tuned into. While staring into her iPhone camera, Rondinelli opened up about the pain surrounding the loss of her younger sister, Rose, who died by suicide in September.

Rose was 14 years old, and two weeks into her freshman year. At the time, her death was the third to shake the Downingtown East community in eight months.

“I don’t want anyone else to go through what I’m going through, because it’s a lifelong sentence,” Rondinelli said at the school board meeting, her voice remarkably calm and steady. “I’m going to live with this forever. Everyone in this community is going to have to live with this.”

“Because it’s four kids,” she continued. “Four kids, and their brains weren’t even fully developed yet.”

“Out of Time”

According to the nonprofit Jason Foundation, four out of five youths who die by suicide give clear warning signs. Such was the case with Rose Rondinelli.

Rose, who is remembered as a witty, free-thinking, and popular teen, was diagnosed with a little-known pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder — referred to as PANDAS — when she was 12 years old. Her family had struggled for two years as doctors failed to pinpoint her symptoms. Physicians eventually said the disorder was the result of an untreated streptococcal infection.

Rose’s family fought long and hard to alleviate her physical and psychological conditions, which grew to include hallucinations, anxiety, depression, and obsessive compulsive disorder. They paid thousands of dollars for doctor and psychiatric visits, including trips to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. They tried a slew of medications. But nothing completely soothed Rose.

“The way I look at it with Rose is that we ran out of time with her,” Rose’s mother, Beth, said to me one day as she sat on a love seat beside her older daughter, Rachel, in their sunny, spacious living room. “Because we would’ve found, hopefully, the right medication that worked. In the meantime, she was tired of trying all of the medications, and when you’re 14, you can’t see the light at the end of the tunnel. You just think you’re always going to be like this.”

For the family of Tommy Walsh, the story is much different.

Tommy Walsh

Tommy was a recent Downingtown East graduate and a freshman at West Chester University. He was the second student to die by suicide, in April, after another recent graduate, an 18-year-old, died in February 2018. Tommy was 20 years old, a handsome, popular student who was on the high school football team and described by many as almost always upbeat.

Cindy Walsh, Tommy’s mother, said she was “completely blown away,” when she received the call about her son’s death. “I had no inkling that anything was ever wrong,” Walsh said. “I was completely blindsided.

“Like every kid, he had anxiety here and there. But nothing to a degree that I thought he would ever do anything to harm himself. He never said anything to anyone.”

Both Beth and Cindy say they believe their children hid the severity of their mental health issues from their friends and family.

“Rose got up every morning, took her showers, put her makeup on, did her hair, had friends, went to football games — you know, everything that a normal teenager would do,” Beth said. “She had her moments, but every teenager does, and we didn’t know what was normal teenage angst as opposed to what’s not so normal and maybe a result of a mental issue going on in her brain.”

A Local Epidemic

While suicides among teens and young adults in the United States have tripled overall since the 1940s, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the rate had begun to decline in the late 1990s. Between 2007 and 2016, however, the suicide rate for children and adolescents ages 10 to 19 again increased, by 56 percent.

Researchers have found that school context can play a role in adolescents’ propensity for suicide and self-harm. A study conducted between 2008 and 2015 noted consistent seasonal patterns in teen suicide, with the lowest percentage of cases occurring during the summer and the highest during the spring and fall, when school is in session.

School board members are aware of the issue: In a report citing state data, they note that the number of 10th- and 12th-graders in the Downingtown Area School District (which also includes Downingtown West High School and the elite, top-ranked STEM Academy) who reported having considered suicide — or feeling sad and depressed — exceeded county rates in 2017.

When an uptick in suicides occurs in a specific geographical area, experts sometimes refer to them as “point cluster” suicides. Downingtown is not the first school district to see such a sharp increase in student suicides in a short window of time. Similar crises have occurred at schools across the nation in recent years, most recently in Utah and Massachusetts, and perhaps most notoriously in the ultra-wealthy Palo Alto, California, which leads the country in youth suicide death rates.

In the wake of or amid point cluster suicides, the CDC urges the affected community to institute an immediate response plan, one that provides support for the suffering and avoids the “glorification of the suicide victims and minimizes sensationalism.” It stresses that parent cooperation is vital.

Greg Brown, director of the Center for the Prevention of Suicide at the University of Pennsylvania, said this is because point cluster suicides can increase the risk of suicide for adolescents in the affected community. Research shows that people (and especially teens) who lose friends or loved ones to suicide are more at risk for suicide themselves.

“Any suicide is heartbreaking,” Brown said. “Especially children. And I think that, hopefully, they’ll be a rallying cry in Downingtown to raise suicide awareness.

“Talking about suicide is the first step in trying to address it. If awareness is raised, usually what goes with that is a decrease in stigma, and people will be more likely to come forward and disclose their suicidal thinking to others.”

“Something Needs to Change”

In the wake of all four student deaths, Beth and Rachel Rondinelli and Cindy Walsh — as well as other students and community members — stress the importance of facilitating conversation and awareness surrounding suicide. They hope to decrease any stigma of mental heath issues and encourage students to feel comfortable opening up to their families, counselors, and each other.

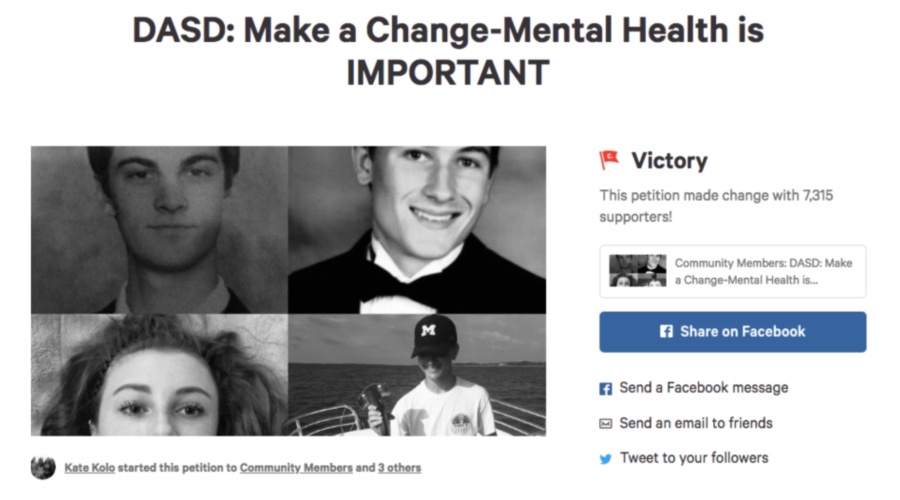

Last week, Class of 2018 Downingtown East graduate Kate Koloseike started a Change.org petition to call attention to the high school’s mental health crisis. More than 7,500 people signed their names in just 22 hours.

Koloseike presented the signatures to the school board at the public meeting last week, stressing that her goal was “to be able to open a conversation with members of the Downingtown School District board on how we can effectively educate students about mental health, help them learn ways to combat [any issues], and give them proper resources to cope with the loss of other students.”

“With these efforts, we can hope that no more students, families or friends will have to experience the pain of losing a loved one to suicide,” Koloseike said. “Young teenagers should not be having to go through this much at an early age. It should not have taken four deaths of teens in our community to get us here, but I am glad we are finally realizing something needs to change.”

Screenshot via change.org

The Downingtown Area School District implemented a number of mental health awareness efforts immediately after Rose’s death, including what’s called “QPR” training for all 7th- through 12th-grade teachers and 9th-grade students. They stressed that they host monthly workshops related to student risk factors in conjunction with the nonprofit Communities That Care of Greater Downingtown. At the board meeting last week, they highlighted new and forthcoming responses, including a “training of trainers model” with support of the Chester County Suicide Prevention Task Force, as well as potential curriculum changes that would place more of an emphasis on how to cope with mental health issues.

In addition, the school board announced that it will host six mental health experts at Downingtown East on Thursday, January 17th, as part of a panel discussion that’s set to begin at 7 p.m. That event will be live-streamed on the school district’s website and precede a mental health roundtable at the high school scheduled for Saturday.

“We want to hear from [experts],” superintendent Emilie M. Lonardi said during the school district meeting last week. “And we want you — whether you’re students, graduates or parents — to ask your questions and let them give us some answers.”

Lonardi said her inbox has been flooded with emails after the most recent student death, with some community members accusing the school of not doing enough to address concerns — which she said “could not be further from the truth.”

Nearly 20 community members spoke at the jam-packed Downingtown Area School District board meeting last week. | Photo by Claire Sasko

Several students who attended the meeting last week said they felt it was crucial that Downingtown East foster better relationships between counselors and the student body. The high school currently employs seven traditional school counselors (in addition to two specialized counselors), which equates to roughly one counselor for every 248 students. One sophomore, Amitha Soundararajan, said at the meeting that she doubted that her counselor “would be able to pick me out of a lineup of three people and say, ‘This is a student I’ve seen twice.’”

Others, like the Rondinellis and Cindy Walsh, said they believe that academic pressure plays a strong role in students’ mental health. Rachel Rondinelli said students are often encouraged to take as many advanced classes as they can handle, and the school, like many high schools in affluent communities today, places a strong emphasis on college acceptance.

Still, every community member I spoke with agreed that the issue is bigger than the school district itself. Maybe, they posited, it has something to do with this generation’s rampant phone and social media use. Studies have linked screen time to higher rates of depression among adolescents and young adults. That might be true. But one thing’s for sure: The issue is complex, and there’s no one cause or solution.

“I wish I could look into a ball and say this is how we fix it,” Walsh said. “I don’t know what to do. I just know I would never want another family to go through this hell.”

At the board meeting last week, superintendent Lonardi stressed that “this is one of those cases where it really does take a village.” As the school district ramps up its efforts, Rachel says some students at East are planning to put up hallway posters with the names of the four students who have died by suicide, as well as the number for the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

For Beth, Rachel and Cindy, what’s important is that parents, students and community members continue repeating the same message: That people are here to help. The sentiment was at the core of Kate Koloseike’s speech before the school board last week.

“To those in the room who are struggling, you are not alone,” Koloseike said. “Your feelings are valid, and somebody loves and needs you. Keep fighting, because this is just the beginning of change.”

For confidential support if you are having thoughts of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or text to 741-741. Learn about the warning signs of suicide at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.