Can a Radical New High School Disrupt Education in Philadelphia?

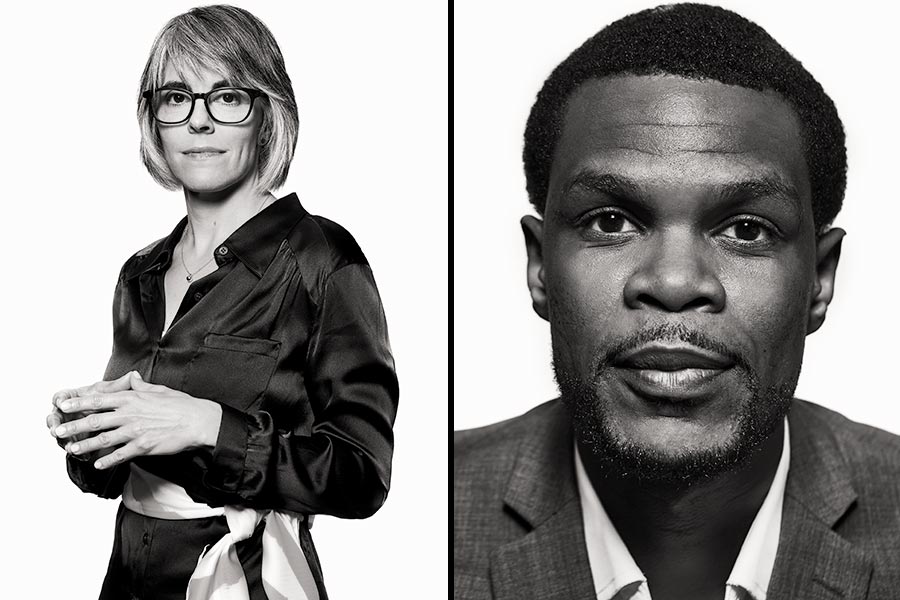

Revolution School team members Gina Moore, left, and Henry Fairfax. Photograph by Matt Zugale

Gina Moore draws a sip of grapefruit-tequila cocktail, a small black notebook cradled in her lap. A financial professional and mother of two in her late 40s, Moore is sitting in the lobby of a Manhattan hotel that’s inconspicuous from street level. A copper-clad doorway leads down a set of subterranean steps to where she sits. Her salt-and-pepper bob fashionably matches the flapper-era-inspired decor.

Moore is trying to locate one of her favorite quotes by one of her intellectual heroes, philosopher John Dewey, who passed away five miles from here in 1952, inside a residence overlooking Central Park. Dewey was an on-again, off-again Marxist and the undisputed “chief prophet of progressive education” in America, as the New York Times said in his obituary. Put simply, he’s not exactly required reading for your average MBA.

Moore’s New York visit isn’t for her day job as a high-powered principal at the Center City investment firm AJO, though; it’s for one of her side projects. For the past two years, Moore has been spearheading a bold soup-to-nuts plan to launch a visionary private high school in Center City Philly — called, fittingly, the Revolution School — that will open its doors in the fall of 2019. The school is premised on a progressive model that views grades as secondary to the production of curious, self-advocating minds. To that end, Moore has been busy researching nontraditional schools around the world, reading Dewey’s theories, and speaking with experts, some of whom she’s hired to co-create the Revolution School with her.

Today, Moore is meeting with a Canadian thought guru named Shane Parrish who runs an organization called Farnam Street. It’s an online community (185,000 newsletter subscribers) of global professionals interested in brainy stuff like mental models, theories of decision making, and something called “double-loop learning.” Functionally, Farnam Street is something of a guidebook to lifelong learning for adults. Moore is intent on adapting some of its practices and philosophies for the Revolution School’s curriculum.

“We can be modeling the same kinds of things that he’s trying to get people to think,” Moore tells me later. “We want to expand the intellectual horizon at a younger age, encourage the ability to spot patterns that exist across our natural systems and lives.”

That’s what the Dewey quote she’s been trying to locate also speaks to; it’s a line from the philosopher’s 1938 book Experience and Education. Moore reads it aloud from her notebook, then texts a photo of it to me for good measure:

For I am so confident of the potentialities of education when it is treated as intelligently directed development of the possibilities inherent in ordinary experience.

Shane Parrish arrives, looking decidedly less Jazz Age than Moore in shorts, a polo and Nike Airs. Moore speaks with Parrish regularly. A month earlier, she spent a weekend in Portugal at one of his retreats. He’s since taken an interest in the Revolution School.

Immediately, they begin discussing education. “We don’t teach people how to learn, and yet we put them through school for 15 years,” Parrish says.

“Not all experience needs to be educational,” Moore says, returning serve. “Some experience is miseducation, teaching you how not to do it.”

When it comes to education in America, almost everyone agrees that elements of the system — if not the entire system itself — are broken. Gina Moore, who is the financial mind and self-described “cheerleader in chief” — fund-raiser, booster and business planner — behind the Revolution School, concurs. Except instead of moving to the suburbs or writing a check to her favorite charter du jour, she’s reaching for something more audacious. Moore wants to disrupt the fundamental vision of what a classroom should look like.

Revolution School team members Noelle Kellich, left, and Tom McManus. Photograph by Matt Zugale

Two months earlier, in June, a couple dozen parents are gathered in a Society Hill living room full of antique furniture and bright Impressionist paintings. They’ve come to an information session held to hype interest in the Revolution School a full summer before open enrollment begins. Moore, dressed in a loose-fitting gray outfit with a name tag attached, is handing out note cards that ask attendees to “share your aspirations for high school.” When the parents settle in with paper plates of Pure Fare — the gluten-free restaurant catering the info session — Moore, ever in motion, skips introductions and asks everyone to turn toward the television for a bit of inspiration.

Photographs flash on the screen: a smartphone followed by an antique phone; a car from today, then a horse and buggy from 150 years ago; a modern classroom, then … well, an early-1900s classroom that’s eerily similar to today, with kids seated at desks facing a teacher standing in front of a board. The video — produced by a corporate-funded education venture called EdCycle — pulls back. The pictures are faux courtroom exhibits being presented by a prosecutor to a judge and a jury. School itself is on trial, it turns out, and the rap sheet doesn’t look good. “Turning millions of people into robots” is one charge. “Killing creativity and individuality” and “intellectually abusive” are two more. The litany of misdeeds gets compiled by the prosecutor, who builds his case for the “educational malpractice” of modern-day schooling.

The brokenness of the education system is a familiar refrain in Philly, and yet, with a handful of exceptions (see “19 Philly-Area Schools Rethinking Education in Big Ways and Small” for some examples of a little progress), it’s remarkable how scant change has been. We live in a supposed golden age of innovation, with digital technology disrupting human existence at unprecedented velocities. Somehow, the futurists can’t crack education, though. Smartboards and iPads haven’t been the game-changers they were supposed to be. Vouchers and charters — whether you believe they’re toxic or a panacea — are reinventing the market but not the classroom. Whether public, private or charter, school is much like it was for our grandparents: Students migrate from room to room, passively absorbing instructors’ commands and, if we’re lucky, becoming inspired enough to finish their homework.

Cognitive dissonance settles in when we imagine something else. “Our biggest issue is communication and narrative,” Moore tells me, drawing a business analogy. “One of the really challenging aspects of selling a school is that it’s a product almost everyone is familiar with. But parents’ opinions of that product are 20 or more years old.”

In other words, the societal image of school remains a force to be reckoned with in spite of the collective wisdom that education needs a hard shake-up. Teachers grading pupils, handing out report cards, and doing it over and over again is a circadian rhythm we’ve all experienced. It’s hard to let that shared history go.

Moore is trying to clear that hurdle with the audience tonight. “Our aspiration for high school is a revolutionary experience,” she says after the video. “An adventure that feeds curiosity and creativity and evokes passion and purpose. A community where we recognize diversity at the heart of our perspective. A structure built to allow teachers to thrive and share in the joy of the journey. We will need to live John Dewey’s insightful and timeless words. … ”

Moore began thinking radically about education a decade ago. She grew up mostly going to public schools outside Harrisburg (the exception was a stint in Germany, where she attended a nontraditional elementary school while her father was working for DuPont) before studying accounting and German at the University of Delaware. But a few things changed in adulthood. Not long after moving to Philadelphia 16 years ago, she began sending her son, Anthony, to the Philadelphia School in Fitler Square. It’s an example (at the K-8 level) of the same type of progressive, project-based education that Moore is advertising at the Revolution School. (A recent TPS middle-school project on pre-colonization and the early Americas offers a window in. During weekly trips to the pine plantation at the Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education, small groups of teenagers made maps, built substantial forts and resolved land disputes — each activity leading into more traditional subjects like geometry, geography and literature. Throughout the three-month-long endeavor, kids journaled on their social and intellectual journey.)

Impressed by her kids’ development at TPS (where she got involved and eventually became board chair) and reflecting on her own career, Moore began to put together the pieces of what kinds of education were meaningful to her. Most valuable were skills she gleaned from interactions with curious minds like Parrish, who inspired her to go further than a textbook assignment ever could.

That, she says, is her “personal motivation” in starting the school. “I feel there’s a whole version of education that would have prepared me much better,” she says. “I’m truly a lover of Philadelphia, and if we can do this, it will be part of a contribution to the city. We have a seed that was planted in the Philadelphia School, an anchor in a way that a lot of places don’t.”

All sorts of schools are promoting the virtues of progressive education as part of their curricula these days, and some schools are even comparable in philosophy to TPS, such as the Jubilee School in West Philly, The Crefeld School in Chestnut Hill, and Project Learn in Mount Airy. Of those, the Crefeld School is the only one that goes past eighth grade. What makes the Revolution School so groundbreaking is the idea that this style of education can succeed right up until college.

But that’s more controversial than you’d think. Even in this room full of families predisposed to progressive models — almost every parent at the info session has a child who’s gone to TPS — there’s resistance. Noelle Kellich, a longtime teacher at TPS and the “head of teaching and learning” at the Revolution School (essentially the principal), explains why to me later.

“What some families think is that the Philadelphia School” — or a similar progressive program — “has been a lovely, wonderful place and has served their kids in all the ways they’d hoped,” Kellich says. But when it comes to high school, parental attitudes shift about what’s right for their kids. “Maybe they need something less caring, less safe, less in tune with them. Something more dehumanizing, so that they can learn to do it, learn to survive.”

Moore leaves time for questions. The conversation inevitably turns toward college. The Revolution School won’t offer AP classes, which sounds all well and good in theory — until a kid gets a rejection letter from Yale. “We believe colleges will be really excited to accept students from a school that has the courage to do this,” says Moore, who points to the University of Chicago’s 2018 decision to make the SAT and ACT optional for applicants.

Later, in private, Moore is candid about how difficult it is to break the educational model we all know.

“Some of the challenge comes in resisting the temptation to build a school in the fashion that people think of as a school,” she says. But she’s determined. “One, that’s expensive, and two, that’s isolating. It doesn’t take advantage of what the city has to offer.”

It’s late July, and after having considered a dozen different rental options in Center City, Moore and Henry Fairfax, the Revolution School’s head of school, are looking at a space for sale at 25 South Van Pelt Street. They make a formidable duo, with Moore dressed in one of her zippy business outfits and Fairfax probing the realtor about air rights. He’s six-foot-four to her five-foot-five, and the building dwarfs them both. It’s a 14,000-square-foot brick fortress hiding in plain sight between 21st and 22nd streets, surrounded by surface parking lots, the Mütter Museum, and the First Unitarian Church.

While they retain a degree of flexibility on the location, the team behind the Revolution School is dead set on being in Center City. “We are a place-based school, which means that kids will be outside the walls of the classroom regularly — not once a month, not a special field trip — partnering with institutions,” Kellich explains later. “We want kids getting out there, mucking it up a bit.”

Inside, the building is a pile of rubble, offering a blank canvas for the Revolution School to make its own. The owner — a smiling, tanned older man with a cigarette in his mouth — won’t give an exact price point, and eventually Moore and her team decide it’s not the right option for them. As with any start-up, the ability to stay nimble could be key, so a rental makes more sense.

“We need to form our character before deciding where the walls are going to go,” she says.

Lack of building notwithstanding, the nuts-and-bolts aspects of the Revolution School are largely in place. It has filed for 501(c)3 status and is a permanent legal entity under the auspices of the Urban Affairs Coalition. Employees like Kellich and Fairfax are receiving salaries and benefits more than a year before opening. Around 90 percent of the start-up money has come from Moore, supplemented by some private individuals. And a financial plan, largely developed by Moore, has been put in motion for the first year. The Revolution School will begin with a class of at least 30 ninth-graders and four instructors. (Teacher pay will be substantially higher than what we’re used to; “Teachers need to be able to afford to send their kids here,” Moore says.) It will then successively add one class each year, along with instructors (at no more than a 10-to-one ratio with students), until it’s a fully formed high school.

Although the tuition will be north of $20,000, Moore has developed a sliding-scale formula that she believes will make the school accessible to students of all income levels. (Most families will pay 10 percent of their pre-tax income, with bottom- and top-end caps.) The Revolution School is broadcasting a commitment not only to racial but also to socioeconomic diversity. Part of the way the school intends to save on costs is the light footprint it will have, using the city — its libraries, green spaces, experts and museums — as its toolbox.

If it all sounds somewhat vague, Moore insists that’s intentional. “If we want to live up to being a school that’s truly progressive, it has to be a living and breathing thing,” she says. “The first class of students is going to play a big role in defining what this could be.”

But even a year before opening, some educators bristle at the Revolution School’s lack of definition and lofty ambitions. “Their website is really uninformative,” says Karel Kilimnik, co-founder of the Alliance for Philadelphia Public Schools and a longtime teacher in the city. That website — a landing page that as of late August was full of inspirational quotes — puts little flesh on the bone. “If you go to the Revolution School, what do you do, spin around all day? Study the Russian Revolution? It’s a name with no substance,” says Kilimnik. “Teachers have been doing ‘project-based learning’ for years. We didn’t market it, but now somebody has made it into a product and is selling it as a curriculum.”

Recruiting families to a school with no name recognition, no building, and little semblance to what we think of when we think of school is a hard sell. But the climate of dissatisfaction around education these days makes it a worthy gambit. Between kindergarten and 12th grade, public-school students in Pennsylvania take, on average, 112 standardized tests with numbingly similar names: PSSA, PASA, NAEP. … There’s no doubt parents and pupils are eager for something different.

“What you learn is that these kids have all been part of a transactional system,” says Fairfax. “We need to take the educational experience from transactional to transformational.”

Fairfax, a youthful 38-year-old, is chock-full of such aphorisms, picked up over his 15 years as an educator at independent schools. He also favors the kind of coachspeak one absorbs playing college basketball at Drexel. Over the course of the past three months, he and Kellich have visited more than a dozen potential feeder schools; they plan to reach 100 living rooms by the end of 2018. “We need to get into homes and recruit, Coach K-style,” Fairfax says.

Without students or a building in place, Gina Moore is betting on the collective reputation of the Revolution School’s leadership to garner buy-in from parents. Prior to joining the school this past summer, Fairfax was a vice president at Girard College; before that, he was director of admissions at the Haverford School on the Main Line. After years on the inside of institutions, nudging reforms ahead slowly, Fairfax decided to make a leap into the unknown. “It’s really hard to move a dinosaur,” he says.

It’s a sentiment shared by each member of the Revolution School team. Jane Shore, the team’s quantitative mind, spent the past decade working at Educational Testing Service — the folks who mastermind the multiple-choice bubbles on the SAT. “My experience at ETS was that we were rarely, if ever, touching the ground, looking locally at our impact,” Shore says. Her role is to monitor the latest research on neurodiversity — the way different students learn — and ensure that the free-form curriculum of the Revolution School remains guided by science, if not the usual statistical outcomes.

Then there’s the head of mission, Tom McManus, who until recently was the high-school principal at the Mid-Pacific Institute in Honolulu, a school that’s earned national acclaim for its progressive approach. Moore recruited McManus, who recently was featured in a book called What School Could Be that’s a sort of reverse Waiting for Superman — a celebration of schools doing nontraditional education right all over the country. McManus is a true believer in the potential for progressive education to take hold here, too.

“In places like Silicon Valley and even in Hawaii, if you’re not in the innovation game within education, the community is telling you to get with it,” he says. “This is happening at a rapid pace. Frankly, it’s not happening as quickly in Philly, but there is a community here that needs these sorts of options as well.”

American education wasn’t always so standardized. It wasn’t until the late 19th century’s wave of mass industrialization that the one-room schoolhouse went away and we began to turn education into a Foucault fever dream in which pupils go in and metrics come out: test scores, graduation rates, college attainment.

Slowly, though, that paradigm seems to be unraveling. Penn’s school of education now has a teacher certificate for project- based learning. Meanwhile, there are a growing number of nontraditional elementary schools in the city, all potential feeders to the Revolution School. Progressive education is a lot sexier than it used to be.

“When my kids started going to TPS 15 years ago, the school was selective, but not what it is today,” says Jennifer Rice, former board chair at TPS. (Moore preceded her as chair.) “Now, it’s ‘the’ school.”

Aside from the raised eyebrows its progressive approach will engender in some parents, the Revolution School will also need to counter the narrative — which will inevitably emerge — that it’s nothing more than an oasis for children of the city’s elite. “Do I sometimes worry about our financing and think, oh no, what if I build a school for rich kids? Yes, I lose sleep over that,” says Kellich. There will be rich kids, of course, but as is true for the Philadelphia School, hitting benchmarks for socioeconomic and racial diversity is central to the plan.

The Revolution School is aiming to be more than just a symbol of what high school can be, a shining city upon a hill. It’s also meant to be a think tank for progressive educators all over the city. It could be the start of a broader movement that brings progressive education solidly into the mainstream.

“If we do it right, we’ll impact all the kids in all directions and the city itself,” says Kellich, who taught in public schools for a number of years. “If that story gets told over and over, I hope people will come and say, ‘Hey, I want to see how you’re doing it.’ And we’ll say yes!”

As with any start-up, getting traction is a challenge. The school was turned down for the one grant it’s applied for, and meetings Moore has had with self-styled disrupters who are throwing money into charter schools haven’t yet borne any fruit. Meanwhile, some people have been irked by the raised fist (of a kid clutching a bunch of colored pencils) prominently displayed on the school’s website. As much as people are angry with the education system today, there’s still a conservatism that reigns over attempts to change it — the same old story in Philly.

Frankly, Moore likes that the school is generating visceral reactions. Revolutions don’t happen quietly. If the founders need to change the website down the road, so be it. The one thing she has no plans to lose is the John Dewey quote that figures prominently: “Give students something to do, not something to learn; and the doing is of such a nature as to demand thinking; learning naturally results.”

Published as “New School” in the October 2018 issue of Philadelphia magazine. Read more about Philadelphia-area schools rethinking education here.