The Badass Days of Boring Bob Casey

He was the U.S. senator nobody noticed. Then came Donald Trump.

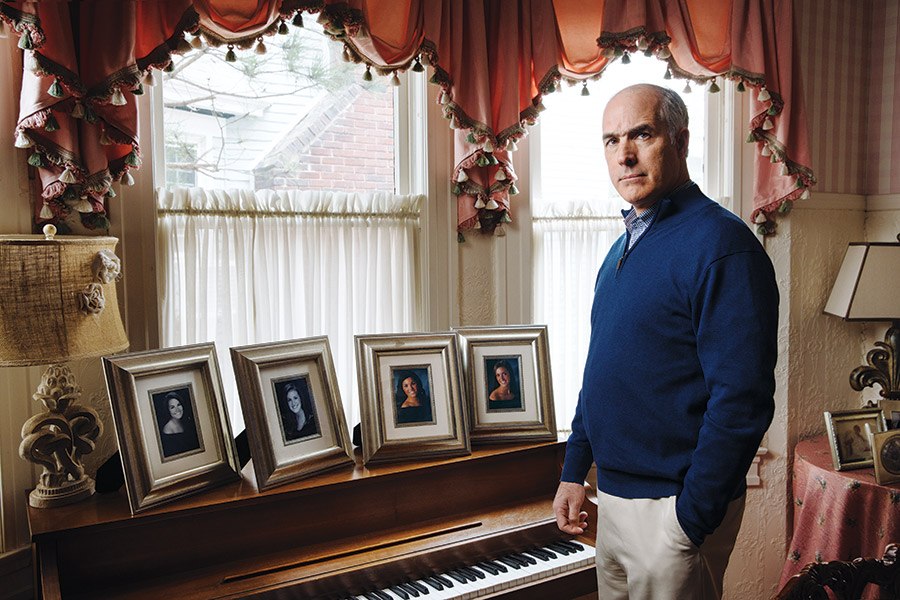

Senator Bob Casey. Photograph by Gene Smirnov

In July of 2016, just as the Democratic National Convention was about to kick off in Philadelphia, a breakfast was held for the Pennsylvania delegates at the DoubleTree Hotel. Senator Cory Booker was one of the speakers that morning, and he roused the troops as only he can, like a revivalist preacher: “Let us go into that convention hall and wake up the echoes of our ancestors. Let us go into that hall and wake up the moral imagination of this country. Let us go into that hall and together, in a chorus of conviction, call to the conscience of our country. … ” And so forth, for several minutes that created a vibe in which everything appeared possible for the Democratic Party.

Then Marcel Groen, chair of the state party, introduced the subsequent guest.

“Our next speaker is a special person, not only because of what he says, and he certainly doesn’t have Cory Booker’s oratory skill” — Bob Casey, the next speaker, burst out laughing on the dais with Governor Tom Wolf as the delegates tittered. Groen quickly tried to save himself by saying how much he loved the Senator and what a big heart he has, bigger than anyone else’s in the Senate, for the people he serves, and, he added, that is more important than speaking well — though the Senator does speak well! — at which point a tall, smiling Casey got behind the mic.

“Hey, let’s hear it for Marcel. Thank you very much for that introduction” — more laughter. “I want the people in the back to know, if you’re really quiet back there, I’ll ask Cory Booker to come back. … I want to first say, Marcel, I appreciate the fact that you so lowered expectations that Governor Wolf and I are bound to succeed.”

Casey truly seemed to be amused, and as he continued, he doubled down, remembering what an Inquirer columnist once said about his personality: “He compared me to oatmeal,” Casey told the crowd. “So just remember that when you’re having your breakfast today.”

Casey is, as pretty much anyone in Washington will tell you, the most regular guy in the U.S. Senate, and Groen had unwittingly given him an easy on-ramp to go right there. Nobody left the breakfast thinking about Casey’s boilerplate message on gratitude and solidarity. Everyone thought: What a nice guy.

There’s a certain problem, however. If nice and respectful and, especially, willing to work with the other side is an outmoded personality type in our national government, you immediately wonder just how Bob Casey has survived in Washington, much less gotten anything done. In fact, his dozen years in the Senate haven’t yielded a great deal — for most of his tenure, he’s been a quiet Obama loyalist, especially on Obamacare. What’s more, the federal government has generally been a mess of inaction for some time now, and Casey might be vulnerable because of the Democrats’ role in that; over the past few years, he has moved left on gun control and gay marriage and immigration, and as he seeks reelection this fall, it won’t be hard for Republicans to paint him as another liberal whose obsession with social issues has left working-class America out in the cold.

Casey got into politics on the coattails of his father, a two-term governor of Pennsylvania with whom he shares a name and impressive eyebrows and help-the-needy beliefs. But whereas the governor was fiery and unbendable, which made him something of a working-class hero, Bobby was always … what? Nice. Kept his head down. Did his homework. Bob Jr. revered his father, and still does, though that doesn’t mean he’s trying to be him. As a former staffer who worked for both Caseys puts it, “His father filled a room. Bobby doesn’t attempt to.”

But then something happened. The optimism Cory Booker and Bob Casey and Governor Wolf had for their party and Hillary Clinton’s candidacy two summers ago in Philadelphia ran into Donald Trump. And just as suddenly, there was Bob Casey, cutting off a night at the Academy of Music to show up at the Philadelphia airport in tux and tails to try and stop deportations due to Trump’s Muslim ban.

And drilling prospective Education Secretary Betsy DeVos about her lack of support for public education.

And firing off aggressive nonstop tweets about the President’s comportment and treatment of judges and gutting of Medicaid and the tax bill that favored the rich. And much more.

Suddenly, it seemed as if Bob Sr., his Irish temper on full display, had popped up.

As for Bob Jr., he knows conservative money and Donald Trump will be coming to Pennsylvania as his reelection bid heats up. Terese Casey, his wife, has already considered the possible monikers the President will paste on her husband: Boring Bob. Bland Bob. Basic Bobby. He knows it’s coming. But that doesn’t seem to bother him at all. Let Trump roll in and do what he does.

Cory Booker might have had it right, two summers ago — that it’s high time to “wake up the moral imagination of this country.” But certainly, no one saw this piece of it coming: Bob Casey seizing an opportunity — provided by Trump himself — to emerge as someone brand-new.

One winter Sunday afternoon in downtown Scranton, the heart and soul of Casey country, I have lunch with the Senator and Terese at a new Italian eatery. The city has struggled ever since its major industry — coal — played itself out almost a century ago. The population was 140,000 in 1930, but only about half that many people live in Scranton now; service, health care and government jobs keep the city afloat. Politics seems to run in the drinking water — Joe Biden is from Scranton, and Hillary Clinton had family here. For the dominant Irish culture in the city, “Politics is the Eagles,” says Margi McGrath, the Senator’s oldest sister.

The Irish-Catholic Caseys, starting with the Senator’s grandfather, became a sort of ruling family, dubbed “the Kennedys without the scandal.” Alphonsus Casey came up out of the mines to eventually go to law school and dabble in local politics. His son Bob, a star basketball player and class valedictorian, went to Holy Cross and George Washington University Law and then began a long, arduous political rise — he lost three races for governor before he ran the state for two terms, from 1986 to ’94. The governor had eight children, packed into a three-story house in Scranton’s Green Ridge section that had one shower. Bobby was number four, the first son. The namesake.

His father was quick to rage for what he believed in and couldn’t abide bullies or greed or cheating. “The governor was very much an economic populist, very pro-union,” says Paul Begala, the CNN commentator who was a speechwriter for Casey in the ’80s. “He put up a statue of the Pennsylvania workingman in front of the governor’s mansion; it was like something out of the New Deal. And he said to me, ‘I want the sons of bitches who live in this mansion to see it every day.’” (The statue has since been moved.) Casey also trumpeted an unyielding pro-life stance. Begala admits that he was scared of the old man, and that his son has the easier personality. Still: A photo of the governor adorns Begala’s office wall. “In a business filled with gray, the governor saw only black and white, right and wrong. He would say, ‘You’re a liar or not, a thief or not.’ He drew stark moral lines.”

The Senator and Margi and their 86-year-old mother, Ellen, all say that the governor was much gentler on the home front when he was back from Harrisburg on weekends. But you have to wonder if, for the namesake son who looks a great deal like him — though his eyebrows aren’t quite as awesome — the governor’s sheer presence was difficult to live up to when Bobby was growing up.

“In high school,” the Senator says at lunch, “all I wanted was to be a basketball player.” He went to Scranton Prep, as did his father; six of Bob Jr.’s siblings also graduated from Prep. “My father, in high school, was one of the five best basketball players in the county, so from the get-go, I had a challenge to meet that,” Casey laughs. He goes on to say that he was a co-captain and starter on his high-school team but not a scorer; his father played basketball in college and was a terrific student and then a strong litigator who was swooped up into politics to become a state senator at 30. “So he was on a fast track.”

Left unsaid is that Bobby wasn’t. After graduating from Holy Cross, Casey spent a year teaching fifth grade at Gesu, a small Jesuit school in North Philadelphia, then got a law degree from Catholic University of America and entered the Scranton practice where his father had worked. Casey had helped on his father’s campaigns for governor and decided to run for state auditor general at the same age, 36, his father had. Though he wasn’t pressed by his dad. “He never talked about it, that I should run,” the Senator says. “The thing about him was, once you chose something, if you asked for advice, wow, would he give it: ‘Here’s what you should do.’” Casey smiles, thinking back. “Like he was coming through the phone.”

Margi says their father’s presence was strong even though he spent his weeks in the state capital, and it still is. During a post-lunch ride around downtown, Casey points out sites that hit close to home: his father’s longtime office building; the church where his funeral took place. (The elder Casey died in 2000, seven years after a heart and liver transplant.)

He’s obsessed, in fact: “See that corner?” Casey says, pointing. “Lackawanna and Adams Avenue — where my father was standing when John Kennedy came campaigning. My father told me about him pulling up in a convertible, waving.” The Senator once went to the archives of the Scranton Tribune and found a photo of that very corner from 1960 — and “because his eyebrow is so damn big, I found Dad right away.”

Bobby was the family scrapbook-keeper for the governor’s exploits. “I felt cheated by missing out on his early career,” he says. Terese Casey laughs now about spying her future husband when she was first getting to know him at Holy Cross, where she also studied: “He was Xeroxing articles about his father in the library.”

Casey with his father and one of his daughters in 1990. Photograph by Gene Smirnov

Casey seems not so much in search of his father, with his memories and sightings, as maxing out his presence, even now. We drive past his and Terese’s handsome, understated Victorian in the Hill section, and a grand vista opens out into the valley below. “I remember as a kid I felt more secure — I had read about tornadoes, and my parents said that I didn’t have to worry about that, we were surrounded by mountains. … Hey, do you want to see Joe Biden’s house?” It’s just a few blocks away.

The Senator’s mother graduated from Marywood College in 1953, right in the former VP’s old neighborhood, and Casey wonders if his mother maybe bumped into Biden: “He would have been a 10-year-old kid.” It feels like we’ve entered a world both long gone and still percolating.

Eventually, gently pressed, the Senator admits that his father’s accomplishments gave him large shoes to fill. “Yeah, at times it’s like, wow, how do you live up to that?”

The governor’s been gone for almost two decades. We visit Ellen in the hundred-year-old house Bob Jr. grew up in; it’s well preserved, though small for two adults and eight kids. Many people point out that the Senator’s softness came from his mother, who’s tiny now with age.

I ask Ellen Casey if her son’s current criticism of Donald Trump seems risky to her.

“I tell him to keep quiet,” Ellen says, “but he doesn’t listen.” The Senator and Margi and their mother, who was the only member of the Casey family to predict Trump’s victory, share a laugh.

There at the end of the living room, over the fireplace, is a grand portrait of the governor, forever gazing down. He died relatively young, at 68, and the date of his double transplant surgery is seared into his eldest son’s mind even now: “June 14, 1993. It’s the only time I ever saw him afraid.”

Bob Casey has always been about getting up to speed, about coming to something. Jeff Batoff, his campaign chair when he ran for auditor general in 1996, says that Casey was passive when he first took office, partly because of his native caution and partly because he had a steep learning curve. As auditor general, he suddenly had 800 people working for him. “Who trains for that?” Batoff says. “He was a practicing lawyer, then running a statewide agency.”

Therein lies the power of the name that got him into the office, and the challenge as well. But Casey plowed into the job the way he takes on everything — carefully, methodically — producing audits that exposed the state’s shoddy handling of nursing homes and group homes for children. He battled Governor Tom Ridge on cutting child-care subsidies to the working poor. He set up forums around the state to get working mothers talking about skipping meals in order to scrape by. He had found his way, an answer to his father. “One thing I’ll never forget that he used to repeat over and over,” Casey has said, “is, ‘What did you do when you had the power?’”

The next step seemed preordained: Casey took his shot against Ed Rendell for governor in the ’02 primary but conducted a lousy campaign, running as the anti-Rendell while Ed shot all over the state in a luxury touring bus shrink-wrapped with his image, popping out to charm the locals and promise big change. In contrast, when Casey made his way around the state to speak earnestly on policy, he could, as Inquirer columnist Tom Ferrick put it, “make Al Gore look like Little Richard.”

But loss toughened Casey, and another test came: Rick Santorum was up for reelection to the U.S. Senate in 2006. Casey, now state treasurer, began getting calls from Governor Rendell and U.S. senators: He had to run. It was a crucial election, and he was the only candidate who could beat Santorum, thanks to his name. But it was off his chosen career path. Terese still remembers agonizing with her husband, during Christmas week more than a dozen years ago, holed up in their bathroom, and how she challenged him: How did he know this path wasn’t the right one? In the Senate he could study issues, take his time, be part of a deliberative body — that felt like Bob. He certainly didn’t want to be on his deathbed feeling like he’d shirked his responsibility to knock off Santorum.

Once he said yes, Casey had to step forward; Santorum was a formidable presence and a great debater. Paul Begala, advising Casey now, showed up one day for a debate prep and dropped a bag of 12 hammers of all sizes on his desk: “Bobby, remember what your father would say: ‘I’m going to drop a bag of hammers on him.’” Begala says he was worried “that he wouldn’t be aggressive enough — it’s very hard to get Bob to throw the first punch.”

With the national spotlight on him, Casey showed in the debate that he was tough and quick enough to go toe-to-toe with Santorum — “That was a seminal moment for Bob,” his sister Margi says — and went on to win the election handily.

Of course, there’s running and then there’s governing. “This is what I knew about Washington when I got here,” Casey says in early March in his office there, which, coincidentally, was once JFK’s. “Zero.”

He had to study fast, given that Joe Biden, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, called before he was sworn in to tell Casey he wanted him on the committee — quite a plum for a freshman. Later, Casey would realize that Biden plucked him because he needed an unthreatening ally, given that others on the committee — including a young senator named Barack Obama — might, like Biden, have presidential aspirations.

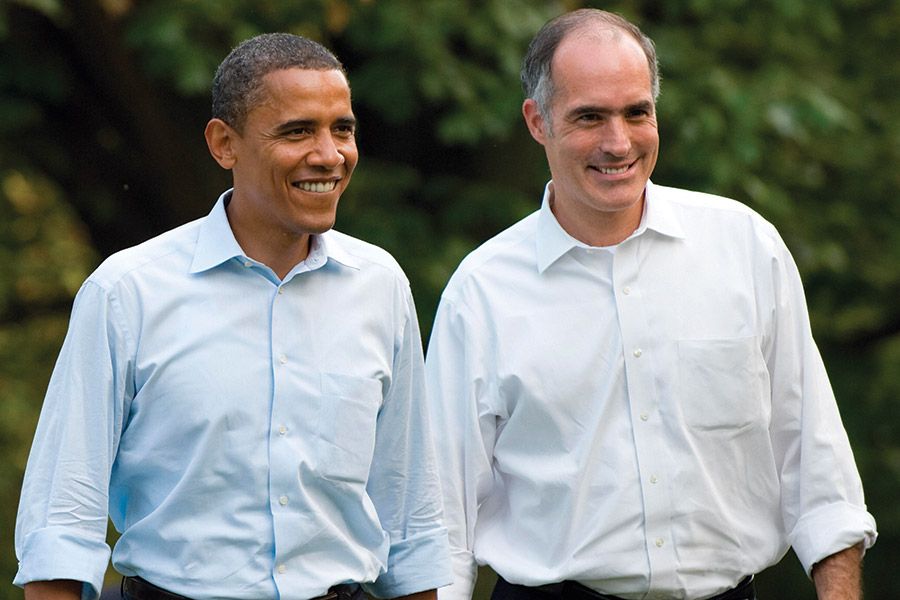

Casey with President Obama. Photograph courtesy of Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images

He had a great deal of work to do. The first time Casey had been abroad (except for a honeymoon trip to the Caribbean) was in 2005, when political supporters took him to Israel to bone up for his run against Santorum, who was well versed in the Middle East. Herein lies the strength and charm of Casey, in a sense: He’s the gee-whiz everyman, hitting foreign soil. Casey, as always, studied hard, and would go on to chair the Middle East subcommittee from 2009 to 2012. He took roughly half a dozen trips to the region, meeting with foreign dignitaries, mostly either making nice or pushing back against some blatantly anti-American stance. He had testy meetings with Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey — “He’s like a movie version of what a strongman looks like” — and took on Lebanon’s Nabih Berri, a Hezbollah ally who trashed the U.S.; Casey ended up storming out of their talk. Senator Ted Kaufman, part of the American delegation, shared the obvious when they were alone: “Well, that didn’t go well.”

What Casey is known for, especially, is listening — for trying to hear out different points of view. Over one long day I spend with him in Washington, his range is palpable: During a meeting in his office with former U.S. ambassador Dennis Ross on the Middle East, Casey leans in intently for an hour and barely says a word. Later that day, a large group of Medicaid activists tells wrenching stories of how funding cuts will ruin their lives, and the Senator is visibly moved and in no hurry. Which may be why Casey always seems to be running late.

His footprint is small, though his fellow senators, at least in his own party, appreciate Casey’s understated diligence. Ohio’s Sherrod Brown and Rhode Island’s Sheldon Whitehouse, Democrats elected to the Senate with Casey in 2006, essentially hit the same point when asked whether Casey is too passive and quiet. “I hate to say this about my colleagues,” Senator Whitehouse says, “but a fair number like to hear themselves talk. When Bob gets up in caucus, you can hear voices quiet. With a lot of other senators, the room has to be gaveled quiet. His signal characteristic is sincerity.”

And then Donald Trump was elected.

Senator Casey wanted to give the new president a chance. When Trump met with Barack Obama in the White House after the election and talked about North Korea, “I’d never seen that look on [Trump’s] face, when he came out,” Casey says. “It was a look of worry in some ways, but my gut, my sense, was that he felt the weight and enormity of the job.”

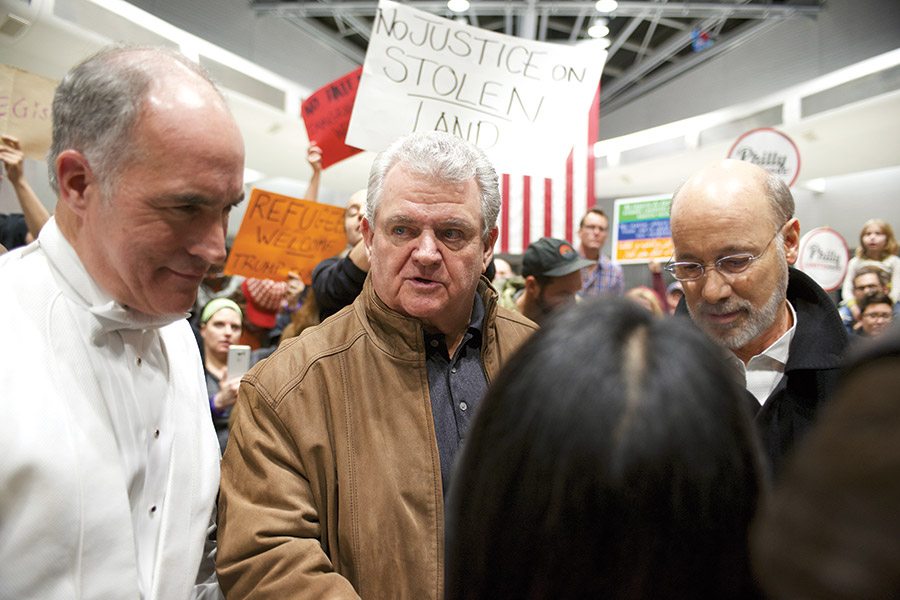

Any hope was immediately squashed. On January 27th, a week after Trump was inaugurated, he signed the executive order banning immigrants from Muslim countries. The next day, the Senator and Terese were on their way to the Academy Ball in Philadelphia when he got a call from Mayor Kenney: Middle Easterners had landed at the airport here and weren’t going to be allowed in, but customs and border patrol wouldn’t let Kenney get involved, since it was a federal matter. So he was calling Casey and Congressman Bob Brady.

Casey with Bob Brady and Tom Wolf at the airport in January 2017. Photograph courtesy of Bastiaan Slabbers/NurPhoto/Getty Images

The Senator, already running late because he’d had to make a pit stop at Macy’s for cuff links, hustled into the Academy to mingle pre-performance. But he couldn’t concentrate on small talk; he needed to go. He and Terese found their seats in the hall, the lights went down, and Casey tapped his wife: “I have to get to the airport.”

When he arrived, 100 demonstrators applauded, but there was nothing Casey could do. Still, a senator showing up at an airport in tails and tux as if he might personally block a deportation, which is exactly what he intended to do, was an instant social media hit.

In fact, Casey was just getting started; a lot was happening fast.

That same day — January 28th — Trump appointed Steve Bannon to the “Principals Committee” on the National Security Council, giving him a huge role in foreign policy. Casey was beside himself — though his staff claims he never really gets angry — and took a very Trumpian tack. He tweeted:

So to recap — @realDonaldTrump’s National Security Council: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs out, former head of white nationalist website, in.

And with that, the gloves were off. There would quickly be more tweets, early in Trump’s presidency:

A President bullying the Judiciary to affirm his unconstitutional acts is outrageous.

We’ve never seen a longer list of nominees that either have a basic lack of competence, definitive conflicts of interest, or extreme positions.

There were hundreds more over the President’s first year, and when I walk the Senator through those early tweets, his famous equanimity lifts to something new. His reaction, for example, to the tweet on “bullying the Judiciary”:

“I felt at that moment and moments like that duty-bound to say something,” Casey says. “I grew up in a household where parents had reverence for institutions, as we all should. It doesn’t mean you don’t question them. Just because you’re part of the judiciary doesn’t give you carte blanche. But this blanket smearing of an entire branch of government — they go through exhaustive confirmation, their lives are turned upside down, they must live up to a judicial code of ethics. This constant denigration of judges, for a ruling on what I would call a Muslim ban — to say that’s beyond the pale doesn’t even begin to describe the outrage. Therein lies deterioration of part of our government.”

For the record, the Senator’s delivery here does not resemble oatmeal even slightly.

When Education Secretary Betsy DeVos was seeking Senate confirmation — also in that crowded first week or so of Trump’s presidency — she deigned to pay Casey a visit in his office. He had two beefs with her: her support of for-profit private schools over public education, and her stance promoting due process in college campus sexual-assault cases. (Casey had sponsored a bill requiring uniform reporting standards for campus sexual assaults.)

Casey smiles that Cheshire grin of his, though not happily, when he shares what he said to Betsy DeVos: “If you are confirmed, you become the Secretary of Education, not the Secretary of Private Education.” DeVos’s expression never changed, but the Senator had said his piece.

Then, one morning in May of last year, Senator Casey called staff into his office first thing: “I need to talk to John Kelly” — then Secretary of Homeland Security — “immediately. Whatever meeting he’s in, tell him to get out of it.”

For months, Casey had been concerned about refugees detained at a facility in Berks County — about 25 people. He’d just gotten word that a mother and her five-year-old son were being deported back to Honduras; it was an asylum case, one the Senator felt hadn’t been adjudicated thoroughly, and he was afraid for the safety of the mother and son.

Casey spent the day trying to keep them in the country, tweeting about their predicament, making calls, checking possible flights on his iPad. Were they going through Miami? Consider: A U.S. senator was pleading with his government, in real time, to save the lives (as he saw it) of two refugees — and he couldn’t even get John Kelly to call him back. Mother and son were deported that day, and Kelly left multiple messages the next morning, before Casey’s Senate office opened, noting them by number — “This is message number three.” His calls were patently self-serving, not to mention a little late. As far as Casey knows now, the mother and son are safe, but the episode left him as upset as staffers have ever seen the Senator.

When you read more of Casey’s tweets from the first year of Trump’s presidency — barbed words about conflicts of interest, health care, North Korea, you name it — it’s impossible not to have it hit: Casey is creating a different kind of presidential record, one in which Trumpian nastiness and missteps are laid out by a senator. It’s a whole new way for our leaders to react to each other, and incredibly bald — as if running the government has become a street fight.

A fight with some political risk for Casey, which is why observers are so sure there’s nothing calculated in the Senator taking on Trump. “If he wanted to stay in the Senate for 35 years, he should be a conservative Democrat,” says Ed Rendell, now a supporter. “Then, there’s no way he loses.”

But you begin to get the feeling that mild-mannered Bob Casey can’t help himself. Jim Brown, who was Senator Casey’s first chief of staff in Washington, worked for Bob Sr. when he was governor. “The bigger and meaner they were,” Brown says about the dad, whom he considered a mentor, “the more likely he was to pick a fight.”

Hello, Donald.

Bob Casey, so tied all his life to his father’s political views — liberal on economic issues, against the tide of most of the party on some social issues, especially abortion and guns — has evolved. After the mass shooting in Newtown, Connecticut, in late 2012, the Senator spent a weekend glued to the TV. He’d always taken the position that gun laws don’t make much of a difference; that was also a practical stance, given how his state is dominated by the NRA. Now there would be a vote coming up in the Senate on background checks and other gun issues. Terese and two of their four daughters were on him: How was he going to vote?

“I was trying to avoid the question,” the Senator admits. But he knew he couldn’t, not when he thought about shooter Adam Lanza. “He was going to kill 300 kids if he had enough time. So I was telling myself, and telling the world, there is nothing the most powerful nation on Earth could do to stop the killing of 300 kids. I thought that position was untenable.” He would vote against the position of the NRA.

He also came around on gay marriage, and while he’s still anti-abortion, his views are much more tempered than his father’s hard-line stance: His Republican opponent in this year’s election, Hazleton Congressman and Trump acolyte Lou Barletta, says Casey “has moved very far left. He’s not the same Bob Casey who was first elected.”

But the real question about Casey isn’t about evolving positions so much as about his style. The Senator acts as if comparing him to his father is a little rich for him, but Ed Rendell and Paul Begala and his sister Margi don’t mind agreeing: The Senator’s stand on Trump, his aggressiveness, is an arc he’s made to his most important mentor. In the past, Margi says, “Bob wasn’t enough of a lightning rod for people to pay attention, and he was okay with that. But when you go to the heart, moving in on stuff that he really cares about, he is like my dad.”

Or, as the Senator’s former chief of staff, Jim Brown, puts it: “Beware the fury of a patient man.”

The passion was always in there, somewhere. The Senator just needed, as Begala says, “to get his Irish up.” It’s easy to see the Trump presidency as a particularly desperate time, but it’s also fair to wonder just what in hell Casey’s been waiting for. If you look back at how he painted the world in ’06, when he was running against Santorum, with our muddled wars in the Middle East and an economy heading toward disaster, why wasn’t he more out front then?

Because Bob Casey is cautious and understated, and he would rather not be noticed. And when Barack Obama was president, Casey could be a good soldier and work behind the scenes on the president’s agenda. Casey understands the complaint about passivity, his and that of his party: “It’s natural — we had a Democratic Senate for the better part of eight years. There’s a natural complacency that comes with it.”

That explanation comes across as weak, given that the current mess of our national politics has been deepening for a decade or more. But Bob Casey, when he came into the Senate, simply wasn’t ready to be out front. “If you’d said 12 years ago that he would become so outspoken,” Ed Rendell says, “that would have been laughable.”

The everyman who got into the Senate mostly on his name needed time — and a trigger. Finally, Casey is firing away at the President, not because Trump is so juicy to take on, and not because he’s fundamentally changed; everyone who knows Casey well says he has always cared deeply about the issues he’s railing about now. The rest of us just didn’t know it.

Perhaps it did take Donald Trump to “wake up the moral imagination of this country,” as Cory Booker called for two summers ago — or, at least, to wake up Bob Casey. No one knows where the careening Trump presidency will end up. But when the President rides into Pennsylvania this summer and fall to have sport with Casey in his reelection bid, an interesting bit of political theater will ensue. Because Boring Bob, about as diametrically opposed to Donald Trump in style and substance as you can get, now seems primed for a fight.

Published as “The Badass Days of Boring Bob” in the June 2018 issue of Philadelphia magazine.