Gridlock: Center City’s Traffic Apocalypse

Philly is thriving like it hasn’t in decades. Just don’t try going anywhere.

Photograph by Gene Smirnov

It’s a good problem to have, all the experts tell me. A symbol of our growth and vitality. A sign of just how hot our city has become.

Which is great, I suppose, but that sunny view of Philadelphia traffic is doing nothing, at this particular moment, to stop me from leaning on my car horn and bellowing at the chucklehead in the SUV in front of me.

“Go, you idiot! Gooo! Are you waiting for an invitation or something?”

It’s a Tuesday morning in early January, and I’m in my car on Chestnut Street somewhere near 36th, dealing with what has now become a fixture of my morning commute: the several-blocks-long, oh-sweet-Jesus-I-think-I’m-actually-gonna-take-my-own-life traffic jam.

Let the record show that such congestion hasn’t always been the case in this part of town. I’ve been making this trek down Chestnut Street from my home in the suburbs for a good chunk of the past 25 years, and for most of that time, things went just swimmingly. Indeed, for the first dozen or so years, the traffic lights were even timed, so that if you went a steady 30 miles per hour you could get from 63rd Street to 30th Street in two, maybe three Tom Petty songs. The timing of the lights got messed up at some point — I’m thinking late Street administration? — but even with a few more stops, the trip was pretty much a breeze.

Then the dark clouds rolled in. First came construction — a whole bunch of cranes and barriers that emerged when they started erecting all those new buildings near Penn and Drexel, butting out into traffic here, taking out a lane there. The straw that broke the Hyundai’s back, however, came late last summer, when I was driving into town one morning and realized that an entire 11-block section of Chestnut Street had been completely reconfigured. Gone: one lane of traffic for cars. In its place: one bike lane. My new reality: a multi-block traffic jam. Every. Single. Morning.

University City, of course, is hardly the only place in town that seems to be in the death grip of Too Much Traffic. Everywhere I go lately, I hear people grumbling about how much longer it takes to drive around town. My friend Joan, for example, moved with her husband to Graduate Hospital a few years ago precisely so they’d have easy access via South Street to the Schuylkill. Now? Thanks to congestion and construction, that route is no longer an option, and she’s forced to crawl across town: “It takes me double the time it used to to get to work in the morning.”

And then there’s the leader of this fair city. Not to tell tales out of school, but last fall, Mayor Kenney was slated to speak at an event this magazine hosted at Penn. As with all our speakers, we asked him to arrive 20 minutes early. When that moment arrived, there was no sign of the Mayor. Fifteen minutes before he was slated to go on, we got a call from his staff: He was almost there. The clock kept ticking: 12 minutes … 10 minutes … eight minutes … six minutes … Finally, with less than five minutes to go, Hizzoner burst through the doors, his face that concerning shade of crimson we Irish sometimes get. “The traffic is freaking ridiculous!” he barked.

Welcome to Philadelphia, Mr. Mayor.

What, exactly, is going on around here? How did our once-easy-to-navigate downtown descend into Carmageddon? And is there anything at all we can do about it?

The answers matter, because the cost of all this gridlock isn’t mere irritation. It’s not just that traffic potentially undercuts the very thing — Philly’s livability — that’s helped spur our recent revival. The deeper issue — who gets to use the roads, and for what? — has set off a series of skirmishes among Philadelphians over the past several years. Car owners like me are bitching about bike riders; bike riders are protesting over cycling safety; urbanists are asking loudly why anybody needs a car in the first place; and everyone is looking at city government and saying: You maybe want to come up with a plan here or something? “At some point, you’ve got to deal with it,” City Council president Darrell Clarke admitted to the Inquirer recently. “People are complaining all over the city about traffic.”

As it happens, the experts are mostly right about what’s caused all this: the increased vibrancy of our city, all the new people, all those new buildings. But there’s something else going on, too. One of the cool things about really digging into traffic is that it gives you a window into a whole bunch of other stuff you never imagined had anything to do with traffic — stuff like human ingenuity and the values of a particular era and our constant need to improve how we move ourselves around.

Or that, at least, was the thought that popped into my head as I inched along in the Hyundai the other day, trying to pass the minutes. It’s possible I now have way too much time on my hands, you know?

Philly, of course, wasn’t built for cars. Particularly in Center City, we’re still living atop the street grid that William Penn and his surveyor laid out some 335 years ago as he planned his then-revolutionary “Greene Country Towne.” In some ways, the history of our city since then has been one long struggle to adapt Penn’s skinny streets — designed for humans on foot and horseback — to new and ever more clever advances in transportation that Penn never could have imagined. The 1850s saw the arrival of horse-drawn streetcars. Over the next 50 years came both electric trolleys and the Market Street subway/El. And then there were automobiles. By the 1950s, there were so many cars, trucks and buses in Center City that we had — guess what? — a traffic problem.

“It’s a little like ‘making America great again’ — we sometimes create nostalgia for times that may not have existed,” says Jonas Maciunas, an urban planner I meet one day for coffee near his home in West Philly. From a transportation perspective, Maciunas — a friendly, broad-shouldered 33-year-old who arrives for our meeting with his son, Aras, strapped to his chest in a Snugli — is pretty much my polar opposite. I live in the suburbs and drive my car into town every day; he and his family don’t own a car at all. When his wife went into labor last year, they hopped in a Zipcar to get her to the hospital. And Maciunas might be the only person I’ve ever met who’s actually taken the train to the Shore.

Maciunas — who recently launched his own urban design practice, JVM Studio — notes that we tend to solve problems based on the values we have at the time. So our solution to the congestion we faced in Philly in the 1950s and ’60s was perfectly in keeping with the ethos of America in the mid-20th century: Let’s build highways! This was the era in which I-95 was constructed in Philly, leveling a handful of neighborhoods and disconnecting us from the Delaware River; the Schuylkill Expressway was built; and master planner Ed Bacon tried to get folks on board with yet another highway, the proposed Crosstown Expressway, which would have gutted neighborhoods near South Street and connected I-76 and I-95. (He failed, thank God.)

As our conversation turns to the present day, Maciunas points out something interesting: Philly’s current traffic troubles don’t actually spring from an increase in the number of cars on our streets. On the contrary, by almost every measure — and yes, there are people who measure this stuff — traffic volume in Center City has gone down over the past decade or two. According to the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, for example, eastbound traffic on Market Street between 5th and 8th streets dropped 37 percent between 1999 and 2015. The problem Philadelphia has right now isn’t more cars traveling on our streets; it’s more things obstructing the streets our cars are traveling on.

The biggest cause of that, no doubt, is Center City’s renewed vitality. Since 2000, the population of greater Center City has increased by more than 30,000 residents — and in the past 10 years, the city has seen jobs grow by 50,000. “It’s basically like we’ve already added Amazon,” longtime Center City District head Paul Levy says, referencing the number of jobs the e-tailer promises to bring to whatever city gets its second North American headquarters.

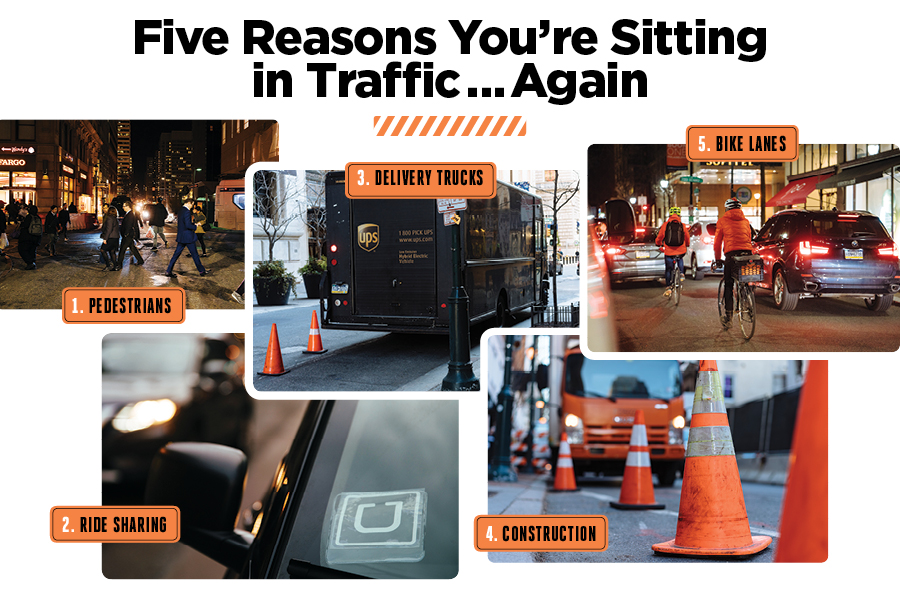

All those bodies that are already here impact traffic in a couple of ways. First, there are simply way more people on the sidewalks in the middle of town than there used to be, which is something you become keenly aware of whenever you try to make a left- or right-hand turn and have to wait for, like, 10 jillion of them to make it through the crosswalk before you can get where you’re going. What’s more, if those streets are only two lanes (as in most of Center City), waiting to turn effectively reduces traffic capacity on that block by 50 percent, which backs up the cars and buses behind you, which can leave vehicles stuck in the intersection a block to your rear, which can then stifle traffic on the previous cross street. A chain reaction! Gridlock!

Aren’t we having freaking fun!

The other issue posed by more people is all the things — apartments, offices, restaurants, retail — we’re building or renovating to cater to them. According to the CCD, at the beginning of last year there were 45 major developments that were either just completed or in mid-construction, with another 15 in the pipeline. While most of those projects don’t impact traffic, there are enough big ones closing off entire lanes of cars or blocking sidewalks that traffic gets snarled even more. “One of the interesting things about traffic now is that it’s bad all day long,” says Levy. “It used to be bad just at rush hour, but now there are issues even in the middle of the day.”

In addition to sheer numbers, new Philadelphians have brought with them something else: different ideas about how one should traverse the city in the first place. If Ed Bacon’s Philadelphia was built around the supremacy of the car, New Philly — more conscious of the environment and its own health — would like the option of getting around town on two wheels instead of four, thanks very much. Due in large part to the pushing (not always welcomed by veteran Philadelphians) of advocacy groups like the Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia, we’ve seen an increase in new bike lanes. (There are currently more than 200 miles of them citywide.) From a traffic perspective, the impact of those lanes is pretty obvious: Take away space for cars to travel in — whether for the new bike lane on Chestnut Street in West Philly or the ones on Spruce Street and Pine Street that have been making Stu Bykofsky’s head explode for nearly a decade — and you inevitably back up traffic. As Jonas Maciunas says of urban transportation in general: “It’s basic geometry.”

The final factor contributing to our current traffic woes is at once the most unexpected and the most symbolic of our age overall: the Internet. One of the most common sights on Philly streets today are cars and delivery trucks — often summoned to a particular spot by a smartphone — double-parked and ready to drop off your latest Amazon order or shuttle you wherever it is you need to go. (Exactly how many Ubers are currently cruising our streets is tough to say; a 2015 study estimated 2,500, but you have to figure the number has only increased since then.) From a convenience perspective, they’re heaven; from a city traffic perspective, they’re hell, seeing as one double-parked Uber waiting for one passenger for just one minute can set off a sequence of delays that ricochets around our entire downtown.

Collectively, all the changes we’ve seen in Philly in the past decade have helped make our city cooler, livelier, healthier and more modern. When it comes to traffic flow, however, they’ve done something no one seems to have thought much about ahead of time: taken Billy Penn’s lovely but skinny little streets and made them, in effect, even skinnier.

In a city that suffers from its fair share of Large Problems, I’ll be the first to admit that whining about traffic might just fall on the wrong side of the unseemliness line. Isn’t poverty a bigger issue? Or schools? Or a more robust tax base? Or the rising murder rate? I grant you all four of those, and probably a bunch more to boot. And yet we’d be foolish to assume that congested streets don’t exact a toll of their own.

Start with pure safety. When you jam a bunch of harried human beings and heavy metal vehicles into a fairly compact space, you’re bound to have a fair number of collisions. And that’s exactly what’s happened. In a recent story in the Inquirer, reporter Jason Laughlin noted that there were more than 12,000 car accidents in Philly in 2016 — more than any year in the past five. One of the most high-profile happened last November, when a 24-year-old woman on a bicycle was struck and killed by a trash truck near 11th and Spruce — the third cyclist killed in Philly in 2017. The accident was yet more evidence of the increasing tension over who owns the roads these days. In protest, bike advocates formed a human barricade on Spruce Street the following day in a call for more protected bike lanes.

But accidents aren’t the only cost. All those idling car and bus engines certainly aren’t helping the environment. And then there’s the economic impact of idle time. “It’s huge — many, many, many millions of dollars,” says Dick Voith. “More than anyone thinks.”

Voith, who’s 62, is another of the traffic nerds I reached out to for this story. He’s an economist — a partner at the firm Econsult Solutions — and another guy who doesn’t own a car. A decade ago, he and his wife moved into Center City, and he’s now a devoted bus rider — though an increasingly frustrated one. “It’s been about impossible to move anywhere on Walnut or Chestnut,” he sighs.

The cost of those delays adds up quickly in terms of lost productivity and extra burdens imposed on riders. “Take 40 working people delayed 15 minutes each way on a bus,” Voith says. “Then multiply that by 100 buses.” For someone like him, the cost gets measured in hours he might otherwise be working. For others — say, a working mom who has to shell out extra money for child care to cover her longer commute — the cost can be even more direct and acute.

Last but hardly least is the impact that delays and congestion have on Philly’s overall livability as a city. A friend who owns a house in Queen Village, for instance, tells me she now thinks twice about making the trek to Rittenhouse to shop or go out to dinner. From an economic standpoint, this might not have a real cost — she can eat somewhere closer to home. But limiting the parts of the city someone can readily get to limits the appeal of the city itself. Ironically, one of the drivers of Philly’s growth and vitality in recent years has been how “easy” our town is compared to larger places like New York. Indeed, one presumes that the quality of life here is one of the benefits city elders listed in their pitch to Amazon for that second headquarters. But what happens if Jeff Bezos and Co. actually accept our offer? That’s thousands of new workers on top of the 30,000 new people who’ve already moved here, on top of all those UPS trucks delivering all that stuff you ordered via Amazon Prime.

Be careful what you wish for, folks. The distance from here to L.A. might be shorter than you think.

Where do we go from here? Well, one thing that’s clear is that the city needs to play a more active role in managing what’s happening — and laying out a more cohesive vision for the future. Uber, Amazon and bike lanes have disrupted us now, but what will happen when autonomous vehicles really arrive, or deliveries start being made by drone? CCD’s Paul Levy notes that multiple entities — including the city, SEPTA, PennDOT, the police and the Philadelphia Parking Authority — currently play some role in traffic management, which can make adopting a unified strategy a struggle. What might help greatly: following the lead of cities like New York that have the equivalent of a citywide traffic czar, someone who can coordinate everyone’s efforts under a single grand plan. (When I reach out to Mike Carroll, the deputy managing director who oversees transportation for the city, he doesn’t mention the czar idea, but he does note that the city is looking at other metropolises for inspiration and ideas.)

In the meantime, there’s a strategy we should be pushing public officials toward: They need to do a better job of manipulating drivers. Before you accuse me of going all Big Brother on Philly traffic, let me just say that one of the things I learned in talking with the traffic geeks is that while we all believe we’re more or less free actors when it comes to choosing how we get around, the truth is that traffic planners are constantly using all sorts of carrots and sticks to prod drivers into making certain choices.

When I meet with Stephen Buckley, for instance, who played a key role in traffic management in the Nutter administration, he tells me that a decade ago, the city was trying to figure out what to do about the lack of turnover at metered parking in Center City. Shop and restaurant owners were grousing that no one wanted to drive into town because there was no available on-street parking. As officials dug into the issue, they figured out that a big chunk of the metered spots were being used by Center City office workers, who were willing to either feed the meter all day or eat the cost of a parking ticket. That might seem crazy, but from an economic standpoint it was completely rational, seeing that the cost of a ticket at the time was only $26 — no more than you might spend at a garage. Solution? Officials doubled the cost of hourly parking and raised expired-meter fines in Center City to $36 — and drivers started changing their behavior. “We were accused of gouging people for more revenue,” says Buckley. “But that wasn’t really the point.”

What other sorts of fiendish manipulations can we mastermind to help unclog our streets? Nearly everyone I spoke with agreed that the first step is to do a better job enforcing the traffic laws that are already on the books — measures like not blocking the box or driving in bus lanes. In late January, City Council president Darrell Clarke announced that he wanted to hold hearings on whether the city could hire civilian workers — rather than more expensive cops — to hand out tickets, as places like L.A., New York and D.C. do.

That will definitely help, but we also need to get creative and try some new ideas to address the new problems. Dick Voith told me, for example, that he thinks we should reduce the number of bus stops in the heart of Center City, essentially going from one on every block to one on every other block. That could help traffic flow more smoothly, which would in turn make riding the bus quicker and more efficient.

As for all those ride-share drivers and delivery trucks that double-park, Voith says we need to reconsider how we allocate curb space in Center City, and soon — because the truth is, we’re only going to see a lot more of them. Should we sacrifice some on-street parking to create more delivery and drop-off zones? Voith, ever the economist, says we could even auction such spots off to the likes of FedEx, UPS and other companies, who’d simply see them as the cost of doing business more efficiently.

Of course, maybe the most effective way to decongest our streets is to get people who don’t need to be driving cars in the city to stop driving cars in the city.

Here, I would be referring to me.

It didn’t take long in the reporting of this story for me to conclude that in the grand hierarchy of people who ought to be taking up precious square footage on Billy Penn’s narrow passageways — from bus riders coming from South Philly to Caviar drivers propelling the new economy — I’m pretty close to the bottom of the heap. After all, there’s perfectly decent public transportation running right through my neighborhood that can have me at my office in basically the same amount of time it takes me to get there in my car. Still, I drive.

Convincing people like me — basically bacon double cheeseburgers clogging the grand circulatory system of urban transportation — to change our behavior is a challenge, though, because so much of the way we choose to get ourselves around is cultural or born of habit. I still drive into the city because … well, sometimes it gets cold outside. And sometimes it rains. And I like to drive. And I’ve always driven. And didn’t Ed Bacon more or less suggest it was my God-given right as a Philadelphian and an American to drive?

Jonas Maciunas says that to alter the habits of people like me, we should start with carrots, not sticks. “If you want people to use public transportation, it needs to be frequent, reliable, and quick to its destination,” he says. That makes sense — although when I think about it, the trolley that runs near my house is neither infrequent nor unreliable. (Other people, I’m aware, aren’t so lucky.) Still, there I am every morning, heading down Chestnut Street in my Hyundai.

A couple weeks after I meet him for coffee, though, Maciunas emails me with an idea for what amounts to a stick: making it harder to park in the city. The best predictor of driving, he says, is the availability of parking. Reduce the number of places where you can ditch your car, and you’re likely to reduce the number of cars overall. It’s a policy some cities are already following. While Philadelphia still has minimum requirements for the number of parking spaces that builders must provide in various areas, other cities are actually imposing maximums. That approach strikes me as harsh — and probably exactly what we need.

Of course, the other possibility in all this, at least over the long haul, is to continue to trust the long, inspiring arc of human ingenuity, the one that’s taken us from only traveling on foot to being able to touch a screen and have a dude show up 20 minutes later with the hoagie we’re craving. In December, Elon Musk, the Wharton-trained entrepreneur and futurist who’s championing electric cars and private space travel and a rocket-fast underground transportation system he calls the Hyperloop, told a crowd at a conference that “public transport is painful. It sucks.” He said it means rubbing shoulders with “a bunch of random strangers, one of whom might be a serial killer. … that’s why people like individualized transport that goes where you want, when you want.”

Public transportation advocates pounced immediately, calling Musk everything from elitist to delusional. He might be both, I suppose, but then again: Our problems are only going to be solved by people who know how to dream a little bit.

Published as “Gridlock” in the March 2018 issue of Philadelphia magazine.