Behind the Tough Persona, Ed Snider Was Kind, Compassionate

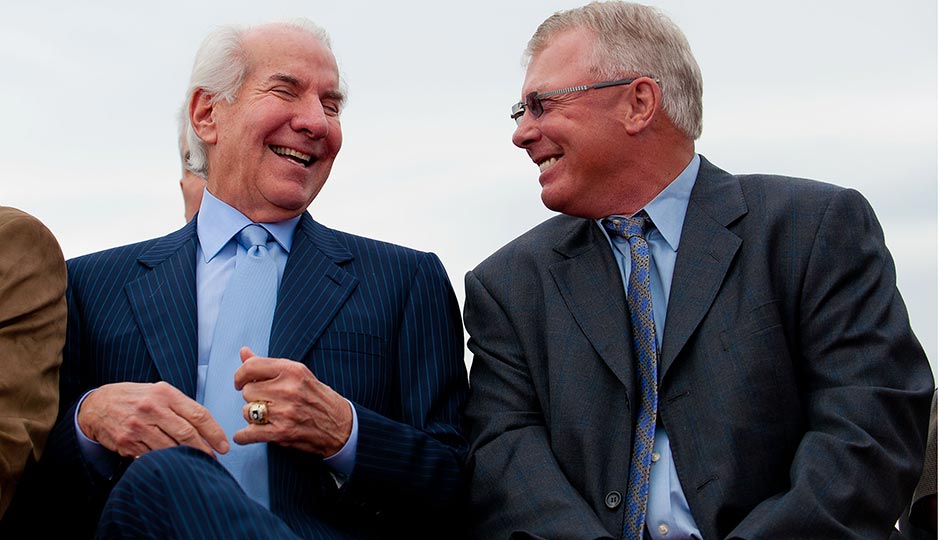

Ed Snider (left) and Bobby Clarke at the 2010 demolition of The Spectrum. Photo | Jeff Fusco

You could get a crippling case of carpal tunnel syndrome trying to list all of Ed Snider‘s accomplishments.

That’s what usually happens on a day like this, when a man of Snider’s immense stature dies — news stories fill with paragraph after paragraph about the professional mountains he conquered, the organizations he improbably brought to life, the honors he collected over the years.

Yes, Snider will forever be known as the wealthy visionary who brought the Flyers to Philadelphia. He was the face of the franchise for nearly 50 years, silver-haired and impeccably dressed, but every bit as hungry for a Stanley Cup championship as orange shirsey-clad diehards who yell at TVs in neighborhood dive bars.

But Snider’s obsession with winning on the ice isn’t what stands out the most in talking with people who knew him well. The anecdotes they shared today, after word spread that Snider had died in California at age 83 from a second bout with cancer, offered a glimpse at a kind and compassionate figure who sometimes emerged from behind a tough-as-nails public persona.

Bob “The Hound” Kelly was just a 19-year-old kid from a small town in Ontario when he laid eyes on Snider for the first time. The Flyers had made the the left-winger their third round draft pick in 1970.

“I didn’t even know where the heck Philadelphia was. The world wasn’t linked back then like it is today,” Kelly said. “It was the first time I’d been around anybody with any kind of power or magnitude. But he embraced everybody with open arms.”

Kelly was struck by Snider’s openness, and his penchant for talking directly with his players about the team: What did they need? How could he help them get better?

Kelly, of course, was an integral part of the team’s back-to-back Stanley Cup championships in the mid-’70s, a peak that Snider spent the rest of his life pushing — unsuccessfully — the Flyers to reach again. “He left a thumbprint on a lot of his players,” Kelly said. “It wasn’t just us. He cared for everybody who played for him, in every era.”

Pat Croce‘s introduction to Snider occurred in an unlikely place: Snider’s home on the Main Line. It was 1979, and Croce was a karate instructor living in Delaware County. He ventured to Snider’s well-appointed house to dole out karate lessons to Snider’s son, Jay.

Croce would spend two hours working with Jay Snider. And then Ed Snider, the business and sports mogul, would invite him to stay for lunch.

“He opened the door to an entire different universe for me,” Croce said. “Just to have an opportunity to get to know Ed, and learn his business acumen and entrepreneurship … I didn’t even know what that word meant.”

Croce was well-acquainted with Snider’s temper — “Oh, we had disagreements, just like everybody else!” he laughed — but he also knew how deeply Snider cared for his employees. In 1993, Croce’s father died. Snider showed up at the viewing, full of concern for his friend.

Another memory sticks out for Croce, from his time as the president of the Philadelphia 76ers: Working late into the night with Snider at the Bellevue-Stratford to hammer out a $25 million contract to hire Larry Brown to coach the team in 1997.

“I love that man,” Croce said of Snider. “He’s truly one of a kind.”

Jump ahead to 2006, when then-Flyers center Keith Primeau made the agonizing decision to retire as he grappled with the punishing effects of post-concussion syndrome.

Primeau said he always believed Snider — and Detroit Red Wings owner Mike Illitch, for whom Primeau also played — were rarities in professional sports: wealthy owners who cared about their players as human beings, not just as performers.

But even Primeau was surprised at how Snider responded in the wake of his retirement. “He called me on an annual basis to get together for lunch, just to check and see how I was feeling,” Primeau said. “It wasn’t uncommon for me to get a call from his secretary, wanting to know if I had a few minutes, because Mr. Snider wanted to talk to me. I’ll never forget that.”

Former Governor Ed Rendell and former Mayor Michael Nutter were both well-acquainted with Snider’s desire to help inner-city kids, which he hoped would be his legacy — even more than those Stanley Cup trophies.

Nutter clearly remembers one of the darker moments of his first year in office, when the city was financially drowning in the wake of the Great Recession. “We had to unfortunately announce that one of the things we were contemplating was the closing of three of our five skating rinks,” he said. “I received an immediate call from Ed Snider, saying that he and his team wanted to step in immediately and help us by running those facilities for us.”

This wasn’t a corporate citizen looking for a warm and fuzzy spot on the 5 o’clock news. Snider’s team — the Ed Snider Youth Hockey Foundation — poured money into the facilities, and offered its acclaimed after-school programs to local kids.

“I’ve never seen anyone so happy, so joyful, at the opportunity to give something back,” he said.

Nutter developed a rapport with Snider that went beyond whichever gala or press conference that they happened to be attending together. Snider knew how to work a room, of course. “But he seemed to never really want to be the star of his own show,” Nutter said.

Instead, he’d recite statistics about the thousands of kids his foundation helped. Most came from low-income families and faced uncertain futures. The foundation offered them a helping hand, a glimmer of hope.

“He was just a good man and a humanitarian who cared about this city,” Nutter said. “We’re going to miss him.”

Rendell was still governor when Snider called in 2010 and explained that he planned to spend almost $6 million of his own money to enclose a handful of neighborhood hockey rinks, so they could be used year-round. He was hoping the state would kick in a few bucks, too. Rendell said he was able to match the donation with money from the state’s Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program.

“He loved kids, and he wanted to make hockey available to kids all over Philadelphia, particularly African American kids,” Rendell said. “He saw that hockey could be a way out for them.”

In his mind’s eye, Bob Kelly can still see the driven businessman and hockey fanatic who took a chance on him all those years ago, who wanted, more than anything, to make the people around him better. “His legacy will burn forever,” he said. “Without question.”

Follow @dgambacorta on Twitter.