Assessing SEPTA’s Suicide Prevention Pilot Program

13th Street Station | Mariam Dembele

Since 2011, there have been 66 deaths along SEPTA’s train, trolley and subway lines. Forty of those deaths have been ruled suicides.

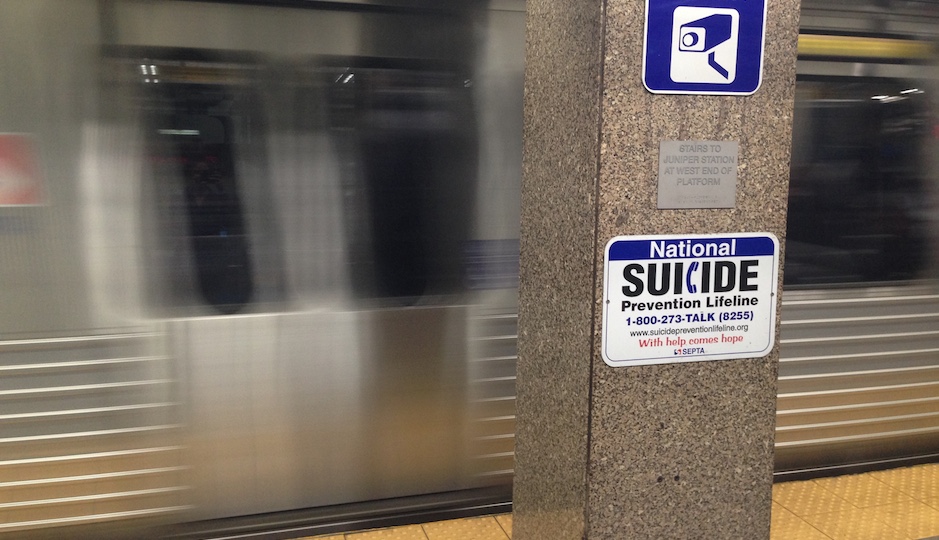

After a high of 10 suicides in 2011, SEPTA started looking into ways to prevent more. In September of 2014, SEPTA began working with Montgomery County Emergency Service to install suicide prevention signs within its stations. It started as a pilot program at the Norristown Transportation Center, then was expanded into 290 of SEPTA’s regional rail, subway stations, and trolley stations and along the Norristown High Speed Line. The bold red, black and blue signs display both the national suicide prevention lifeline number and website. At the bottom they urge, “With help comes hope.” Currently, there are approximately 1,000 up. Now almost one year since the last sign was posted, statistics tell a couple of different stories about how effective they’ve been.

The mortality numbers have remained relatively static: In the past year, there were 13 deaths along SEPTA lines, seven of which were determined to be suicides. This mirrored the trend lines from the past five years. SEPTA has averaged 12.8 deaths and 7.6 suicides per year with the most common location being along the regional rail lines. However, Scott Sauer, SEPTA’s assistant general manager of system safety, notes that it’s difficult to decipher trends since the numbers are relatively small and the incidents are spread out throughout the region.

However, both the Family Service of Bucks County and Montgomery County Emergence Service (MCES), two of the centers which receive hotline calls, have reported an increase in callers since the signs have gone up. Although it’s difficult to say for certain whether the calls have come from people who have seen the signs, Sauer takes it as an encouraging indication that the signs are having an effect on a problem that has no one solution.

“It’s a difficult problem to solve because it’s cultural,” said Sauer. “It’s something the industry is grappling with.”

The problem stretches far beyond Philadelphia’s borders. Nationally, the Federal Railway Association reported that in 2015, from January through November, there were 220 suicides. For the full year of 2014, there were 260 suicides. (It’s important to note that the FRA does not include subway and trolleys in their data. Additionally, their numbers are updated as medical reports determine that a railroad-related death has been ruled a suicide).

Over half of railroad-related deaths are due to trespassers. To combat accidental injures caused to those who are wandering near the tracks, Sauer said SEPTA will be launching a pilot audible alert system at their Fern Rock station that will sound when a train is approaching.

However, that might not account for purposeful deaths. In a study conducted by the FRA on trespasser fatalities, they found that every 1 out of 4 was a suicide. The Inquirer notes that other studies have said that close to half are suicides.

Railroads across the nation are hoping that suicide prevention signs can put a dent in that number. In 2010, New Jersey Transit posted suicide hotline signs in all of its rail stations and on trains, as did Caltrain, a California commuter rail.

Tony Salvatore, the director of development at MCES, is confident that the SEPTA signs are having an effect. He recalls a chilling call they received from a young man at a train station in Delaware County.

“He wanted either to take his life, or to see what it would feel like to lie down next to the train,” Salvatore said.

One of the phone operators stayed on the line with the man for about an hour and was able to talk him down, while MCES sent someone to check on him.

While that may have been a life-or-death situation, Salvatore believes that one of the unrecognized benefits of the signs is simply taking away some of the stigmas surrounding suicides and letting people know that there are resources available for those that are depressed but not on the brink of suicide.

“Taking your life is a process,” said Salvatore. “People crash and burn piece by piece over time.”

“[The signs are a] very subtle way to reach people, it tells people that somebody somewhere is there,” Salvatore added.

He said a large chunk of the increase in calls he receives are from people asking about how they can help with suicide prevention, and from those who are concerned about friends and family members.

“It creates a community awareness,” said Maria Picciotti, the call center coordinator at Family Service Association of Bucks County. “It helps make it an open conversation and get people not to be afraid to say the word suicide.”

Picciotti said that they’ve seen a large increase in calls and have hired two additional part-time employees to be available during the morning and evening hours.

“If those signs only saved one life they’re worth it,” said Salvatore. “If they only get one person to call they’re worth it.”

Follow @mariamdembele on Twitter.

For confidential support if you are having thoughts of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255). Learn about the warning signs of suicide at the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.