Bullets and Bigots: Remembering Philadelphia’s 1844 Anti-Catholic Riots

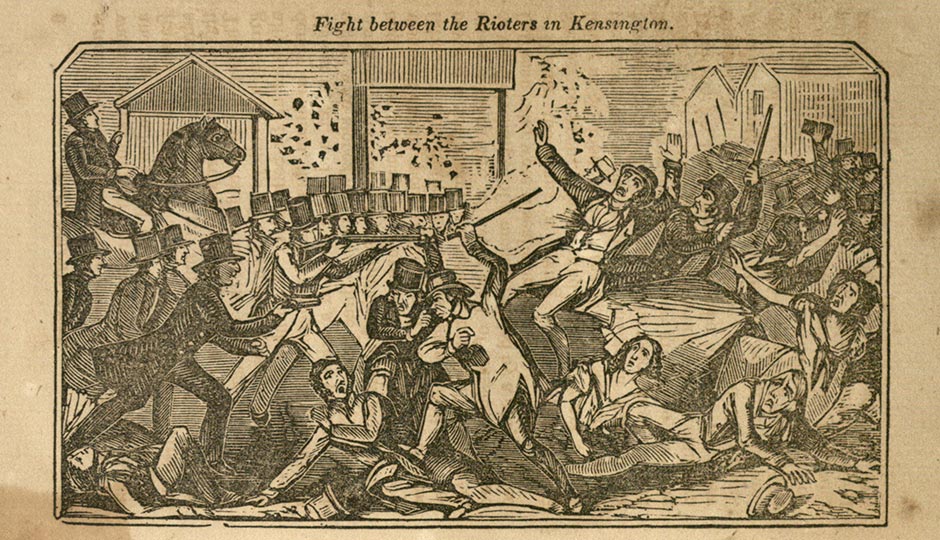

From “A full and complete account of the late awful riots in Philadelphia : embellished with ten engravings”, part of Villanova’s Falvey Memorial Library’s Chaos in the Streets! The Philadelphia Riots of 1844 collection, used under a Creative Commons license.

It started with a Bible, of all things. Bishop Francis Kenrick, who, like many of the newest Philadelphians in the mid-1840s, had come to America from Ireland, learned that the city’s public schools, which started each morning with a Bible reading, were using the King James version of the Good Book. That was the Protestant Bible; Catholics used what was known as the Douai Bible. Different books for different faiths. Anyway, the Bishop — he’d founded St. Charles Borromeo Seminary in 1832, the same year he earned commendation from Philly Mayor John Swift for his and his fellow Catholics’ service to the city’s sick in a cholera epidemic — had asked the Board of Controllers of the Philadelphia schools if Catholic children might read the Douai Bible instead of the King James. The Board of Controllers approved the use of other versions of the Bible, and that was that.

In one sense, the board was yielding to the inevitable. Irish Catholics were pouring into the city; between 1830 and 1850, the Catholic population rose from 35,000 to 170,000, and the number of Catholic churches from 22 to 92. As always happens in such paroxysms of change, the extant population wasn’t thrilled with the newcomers. Imagine if, say, thousands of Syrian refugees suddenly descended on the city, with their own peculiarities of language and culture and a different religion. There was gossip about the Irish. Innuendo. Insinuation. Talk of a papal plot to rule the whole world and stamp out other faiths …

It took another year and a rumor to light the fire, though. The story spread that a school director in Kensington, a Catholic named Hugh Clark, had visited a girls’ school and demanded that its principal put a halt to Bible reading completely. Clark insisted he’d been misunderstood; when he observed a group of Catholic students leaving class for their own Bible reading, he merely remarked that if the Bible was causing such division in classrooms, perhaps it would be better if it wasn’t read. But the rumor grew, and flew, among the city’s less-recently-settled Scots-Irish Protestants: Hadn’t it been Bishop Kenrick who wanted the different Bible? There was no pleasing those people. What was wrong with the King James, for heaven’s sake? (Just imagine what Twitter would have made of all that.)

On May 3, 1844, members of a political organization called the American Republican Party — known as “nativists” because they favored the rights of those born here over those of immigrants — held a public rally in Kensington, where many of the Irish Catholics had settled. Local residents took umbrage and attacked the platform where the nativists were speechifying. The nativists fled, but three days later they returned — thousands of them. Fights, predictably, broke out between them and the Irish Catholics. Somebody started shooting from the windows of buildings. Several nativists were killed, inciting their mob to attack the Seminary of the Sisters of Charity and a few local homes. Two more nativists died, and dozens of people were injured.

And where were the police, you might wonder? Kensington back then wasn’t part of the city proper. The peace was kept by a district constable, who, when there was trouble, was charged with summoning the county sheriff, who would set up a volunteer posse. But this time, the sheriff and the posse, armed only with clubs, couldn’t save the day. The following morning, the nativists called on fellow citizens to “throw off the bloody hand of the Pope” and marched on Kensington again. Gunfire erupted once more, and this time the local fire station, 30 homes and the Nanny Goat Market burned before the state militia managed to disperse the crowds.

Bishop Kenrick called on his fellow Catholics to maintain the peace, and people hung flags from their windows and scrawled “Native American” on their doors in charcoal, hoping to escape more violence. But the nativists descended on Kensington for a third day, burning down St. Michael’s church at 2nd and Jefferson and finishing off the Seminary of the Sisters of Charity. The mob then torched St. Augustine’s at 4th and Vine as well as a nearby school. All told, 14 more people died in the mayhem, 50 were injured, and hundreds lost their homes.

Then the city settled down. A curfew was enacted, and state militia were stationed at the remaining Catholic churches. Bishop Kenrick ordered those churches to stay closed on the following Sunday, and urged his parishoners not to fight back against the nativists. Mayor Swift pleaded with both sides for peace. A grand jury, sadly but predictably, blamed the rioting on “the efforts of a portion of the community to exclude the Bible from the public schools.”

It wasn’t over yet. On the opposite side of the city, in Southwark, another series of riots erupted after the priest at St. Philip Neri, hearing that nativists planned a Fourth of July parade in the neighborhood, requested muskets from the Frankford Armory, to be used in defense of the church if needed. The parade passed without incident, but the following day, thousands of nativists stormed the church, demanding removal of the muskets. The crowd grew; cannon were rolled onto the streets. Rocks were thrown. Prisoners were taken. The cannon were fired at the crowd, then turned around and fired at the church. The fighting went on for days, with the citizenry utilizing knives and chains and broken bottles as weapons. Fifteen more people died, and 50 more were injured. It took 5,000 militia to quell the rioting. A grand jury blamed the Catholics. Again. The riots attracted national attention and became an issue in the presidential election that year.

A nativist recounting of the Irish Catholic participants in the riots included this description:

Great numbers of women now joined the fray, and no tigress ever fought more desperately or frantically for its prey, than these did for their foreign masters. … “By the Holy Virgin!” they yelled, as their unbound hair streamed around their hideously distorted visages.

Sounds like something Donald Trump might say about Muslims, doesn’t it?

In the wake of the fighting, Philadelphia consolidated its outlying suburbs into the city proper, and standing police forces were established. Bishop Kenrick gave up fighting over which Bible to read in schools, instead creating the city’s Catholic school system — the first in the nation. He began construction of the Cathedral Basilica of Sts. Peter and Paul, eventually became the Archbishop of Baltimore, wrote his own translation of the Douai Bible, and died in July of 1863 after reading an account of the terrible carnage at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Nowadays in Southwark and Kensington, it’s hard to tell the Catholics from the Protestants. The houses that had been destroyed were rebuilt, in time. So were the churches. St. Michael’s celebrates the Mass in Spanish every Sunday.

(View an online account of the 1844 riots from the Villanova Library Digital Collection here.)