Um, Chris? Let’s talk

I could spend most of my day dissecting Chris Freind’s morning blog post, which, if I may, can be fairly summed as follows: Taxes bad, spending bad, schools bad, gambling bad, Ballard Spahr bad, ergo, Rendell bad. It’s a rather simplistic line of reasoning, to be sure, but on some of those points you won’t find me in disagreement: The state hasn’t given much thought to the repercussions of its gambling expansion (nor, for that matter, to the environmental impact of widespread Marcellus Shale drilling, the cash cow that Freind’s man crush, Tom Corbett, only wants to milk more, and with less regulation). The state legislature is indeed a mess, corruption is far too rampant, and Fast Eddie (and the state in general) are much too quiescent to Comcast.

But I don’t have all day. So, I’ll touch on a couple of things that jumped out at me:

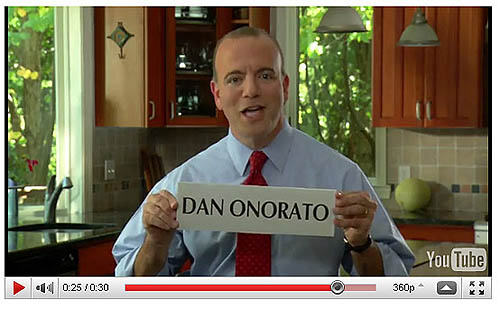

Many analysts postulated that Dan Onorato was defeated in the governor’s race, and the Democrats lost control of the State House, because of the national Republican tidal wave, with Rendell playing little role in that result. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Um, really? Let’s go to the tape.

Onorato was Big Ed’s fault? Really? Onorato—the guy whose campaign was so terrible that he was telling people how to pronounce his goddamn name a few weeks before the election—lost because nobody liked Ed? Sure, the gov’s unpopularity probably didn’t help, but to discount the external forces and winnow that election down to one variable (Ed) strikes me as the shallowest of analysis.

Some true facts: The Rs and Ds in this state have traded the governor’s mansion every eight years since, well, forever. This was Corbett’s year. I don’t know precisely why things work out that way, but they do. Of course, chalking up Corbett’s win to that bit of barroom trivia is rather shallow in its own right. In its postmortem, the Inky attributed Onorato’s loss to his failure to dominate—or win, actually—his home turf of Allegheny County, a fact that, to my mind, speaks more to Onorato’s weakness as a candidate (after all, these are the folks that ostensibly know and should like him) than to Rendell’s weakness. I guess you could argue that folks in Pittsburgh hate Rendell so much they took it out on Onorato, though I’ve not seen any evidence to that effect. In both elections, Philly accounted for about 11 percent of the statewide vote, and Onorato and Rendell got a relatively similar share of the count (Rendell performed marginally better). Over in Allegheny, Rendell won; Onorato lost, albeit not by much, but still, by enough.

But Onorato also got whupped in the southeastern ’burbs (compared to Rendell), and throughout much of the T. Freind’s position is that many of these folks turned on Rendell, and took it out on Onorato. Maybe some of them did. But that’s not why Onorato lost the election. Nor is his inept campaign, although here again, he didn’t do himself any favors. The simple reality is that politics aren’t really all that local anymore. Elections are won based on who shows up. For this election, well, look for yourselves:

The electorate, both here and nationwide, was older, more conservative, and whiter—and worse for Democrats, the whites who showed up tended to be more poorly educated, which means they were much more likely to vote Democratic. It was a good year for Republicans—both nationally, and in Pennsylvania, not because gobs of people up and changed their minds from just a few years ago, but because Republican voters, and particularly older voters frightened to death by the hubbub over health care and those ubiquitous ads claiming Obama was going to hack $500 billion from Medicare. The enthusiasm gap was very, very real.

Of course, 2002 was a good year to be a Republican, too. But it wasn’t like this; and though I didn’t live in the state, I would also guess that Rendell was a much more effective campaigner in 2002 than Onorato was in 2010, especially in the southeastern ’burbs and the T. (He couldn’t have been much worse.) Here’s the rub: Pat Toomey would not have been elected senator in 2002 (or 2004, 2006, 2008, for that matter). He would’ve been far too conservative for Pennsylvania in any of those years. No, Toomey was the beneficiary of the political climate, even though he was running against a skilled and effective (and late-closing) Sestak operation. Rendell had nothing to do with this race. And yet, Onorato, who ran a piss-poor campaign in the same climate against a stronger and better funded candidate (Corbett, after all, made a name for himself battling Harrisburg corruption, which definitely has a bipartisan appeal) still managed to garner about 46 percent of the vote.

Sestak got 49 percent.

That’s 3 percentage points. Factor in Onorato’s terrible campaign, Corbett’s superior candidacy and fundraising (he got millions of dollars in sweet, sweet Marcellus Shale money, remember), and Toomey’s, well, wing-nuttery, and quite frankly, I don’t see how you can put Onorato’s loss on Rendell’s shoulders. Unless, of course, facts are mere speed bumps on the road to calling Rendell a failure. (Reaching a conclusion then working backward seems quite common in conservative punditry these days, but I digress.)

Bone of Contention 2:

But if you read the glowing editorial in the Inky this past Sunday, you’d have thought Rendell walked on water. Consider these beauties:

“…he is leaving office as one of the most effective and capable governors that Pennsylvania has ever had.”

Nothing like telling 70 percent of Pennsylvanians they are dead wrong. And who says the media is elitist?

Seventy percent of Americans, and probably 70 percent of Pennsylvanians, have been dead wrong many, many, many times in our nation’s history, and if that makes me an elitist, well, so be it. Asserting a polling snapshot as the pinnacle of absolute truth—also: “Poll numbers don’t lie”? Hahahahaha—is about as naive as it comes. Remember when Bush II left office at 22 percent approval, down from 90 percent (!) in 2001? Or when Obama was at 66 percent? These things fluctuate. And let’s not forget, as Freind is wont to do, that Rendell governed during a very tumultuous time: The death of manufacturing here and throughout the Rust Belt had been an anchor around the state’s neck even before the Great Recession, which made things a hundred times worse. That’s not to absolve nor champion Rendell, but the Inky is right that, if the casino revenue and the Shale revenue (though Corbett opposes a severance tax, because he’s basically owned by Big Gas) come through in the years ahead, this state’s fiscal health could improve significantly, and Rendell may be seen a bit differently. Or maybe not. But to label Rendell a failure now—and in absolute terms, based largely on Onorato’s ass-kicking—seems to overstate the case considerably.

Bone of Contention 3:

[From the Inky:] “…Rendell has led the state to impressive gains in public education.”

How? By throwing an endless supply of taxpayer money into the black hole we call Philadelphia’s deathtrap schools? If more funding was the solution, we’d have the best and brightest students. Instead, we have unacceptable dropout rates, functional illiterates, low SAT scores and unaccountable teachers’ unions. But God forbid we try the only solution proven to work — school choice. The unions wouldn’t like that, and far be it for the Governor to offend a big contributor.

We do have unacceptable dropout rates, and piss-poor literacy rates and SAT scores. (The predictable canard about the teachers unions will be left for another day.) But let’s talk about Freind’s proposed “solution”—school vouchers. What he’s talking about, under the “school choice” euphemism, is the idea of basically giving parents checks to send their kids to school, whether that school is religious or private or public or a charter or whatever. Setting aside the First Amendment implications—not sure about you, but I sure as hell don’t want my tax dollars going to some fundamentalist school where kids are taught that the world is 6,000 years old and dinosaurs rode on Noah’s Ark—let’s talk about why “school choice” “works.” It allows those parents who care enough to move their kids out of neighborhood schools, which (despite what Freind says) are far too dangerous and underfunded, at least here in Philly, and into Catholic schools or private schools in Jersey or the ’burbs. Charters and privates work—I attended a private school K-12, FWIW—because schools can pick and choose who they want. If the kid causes a disturbance, or has a learning disability, or has disinterested parents, or does poorly, the school can kick them out.

Traditional public schools don’t have that option. And when charters and privates remove from the inner cities those kids whose parents are involved and who learn and who don’t cause problems, you’ve basically given up on everyone else. And from there, those schools only get worse, and good teachers don’t want to teach there (unless you throw piles of cash at them, and sometimes not even then), and the downward spiral continues. Vouchers are a phony solution.

Also, contra Freind, they Do. Not. Work.

Last year, a Congressionally mandated review of the program by Department of Education researchers concluded that there were no significant differences between the test scores of students who received a voucher and those who applied but, not receiving one, attended public schools instead.

Parents of students taking part said they believed that the private schools their children attended were safer than public schools, the study found. But the voucher students themselves rated their school experiences no more highly than did children attending neighborhood schools, the study found.

The key here, the independent variable that matters above all else, is the parents. If the parents cared enough to try to get their kid a voucher, chances are, that kid will do OK. If not, well, there you go. Vouchers don’t fix any of that. They were invented as an attack of public education writ large, mainly by suburbanite parents who believe the state should subsidize their kids’ private school education.

All right, I have a meeting now, so we’ll conclude this exercise.