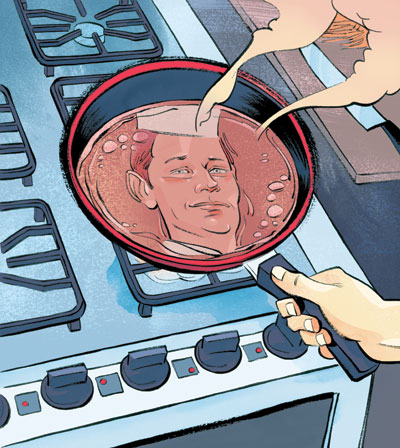

Gastronaut: Arts and Crafts

Illustration by Kagan McLeod

I saw this coming years ago. Not because I’m clever or prescient or some kind of unappreciated soothsayer of cuisine, but simply because I was on the front lines. I was a restaurant critic in Denver, Colorado, back during the second boom of New American cuisine.

I saw this coming years ago, but it had no name — not until GQ’s Alan Richman gave it one a few months back. He wrote about young chefs, exclusively male, working “with like-minded discipline, hardly ever haunted by doubts, seemingly in possession of absolute confidence.” He called it “Egotarian Cuisine” — food that is “intellectual, yet at the same time often thoughtless … straddling the line between the creative and the self-indulgent.” More to the point, food that is created solely, and with arrogant singularity of vision, to please the chef. Not the owners. Certainly not the customers. It’s food as memoir and manifesto. And often, it’s terrible.

I saw this coming with my own eyes at a place called Root Down, in Denver, in the form of a kitchen with no executive chef and a menu made by committee, by all the cooks involved in its execution — a kind of culinary collectivism that resulted in a tofu potpie with winter vegetables and pomegranate syrup. It was an awful dish, horrifying in its own Frankenstein-ism, and bad enough that I still remember it today — the tofu like chewy cubes of kitchen sponge, the bittersweet and flowery pomegranate syrup like what I imagine it must taste like to lick a Mediterranean grandmother.

There’s nothing new about cooking as autobiography. Really, all the best cooking has been that forever. But egotarianism is cooking without a filter. Without any reasonable connection to an established order of things — a cuisine, a canon, the faintest notion of what human beings actually like to eat when they’re hungry. It is cooking purely for the glorification of the self — a show-offy declaration that this tofu potpie or kimchi taco with yak butter rémoulade is something that only I, the chef, in my awesomeness, could create.

In Philly, we have this kind of thing happening everywhere. The nature of our scene (i.e., a historically low tolerance for bullshit) puts a governor on the greatest sins and excesses of style (look what happened to Sophia’s and the second incarnation of Le Bec, or is happening right now at Avance as it retools); those who ignore completely the tastes of their neighbors are going to pay for it. But, in counterpoint, we also have a restaurant like Volvér (reviewed here), which takes the idea of food-as-memoir and raises it to a level where every single plate is torn, piece by piece, from Jose Garces’s backstory.

As has always been the case, the truly great artists among us can get away with that. They can take almost anything — joy, pain, paint, stone — and turn it into art that is worth the price of admission.

But as has also always been the case, in every neighborhood, city and nation, there are far more bad artists than there are great ones. And the trick with egotarianism will always lie in being able to tell the masters from the hacks.

Originally published in the July 2014 issue of Philadelphia magazine.