Reading Viaduct Park Would Make Getting Around Philly Easier

The Reading Viaduct today — and tomorrow? | Photo by Malcolm Burnley and rendering via Friends of the Rail Park

Last September, after visiting the new Whitney Museum in New York, I climbed up to the High Line for what I thought would be a breezy stroll with gorgeous views of the Meatpacking District. How wrong I was. Between the people jockeying for avant-garde lawn chairs and the gaggles of camera-toting tourists, the foot traffic crawled along at an infuriating pace.

The park was designed for 600,000 visitors per year; last year, there were 6 million. Though the High Line remains an international beacon of innovative green space (it has also invited lots of deep-pocketed developers into the once-sleepy Chelsea neighborhood), it’s not a functional piece of the urban grid. You can lick all the $8 popsicles you want there, but don’t fool yourself into thinking it’s a good way of getting around the Lower West Side.

All of which made me believe that the rallying cry in Philly to create a High Line-esque park out of the rusting Reading Viaduct and adjacent railroad tunnels — together, they form a continuous stretch of land going from Chinatown to Fairmount Park — was mostly about beautification, and not at all about improving mobility. That’s why I left it off Philly Mag’s recent list of “20 Smart Transportation Ideas Reshaping Philadelphia (and Your Life).” Was it one of the 20 coolest urbanism projects around? Surely. But was it going to change the way we moved around the city? Meh.

Someone begged to differ. “Think about being in West Poplar or NoLibs, riding a few blocks to Fairmount and 9th, taking an elevator up onto the Viaduct and then riding all the way to PMA or Boathouse Row, and [you] only have to stop for cars when crossing Kelly Drive,” Michael Garden wrote to me on Facebook. Alright, that got my attention.

Garden is a board member of Friends of the Rail Park, a/k/a the main organization advocating for the rail park project along with Center City District. He made a good pitch, and offered to demonstrate the multi-modal merits of the proposal while giving me a tour of the would-be rail park. I duly accepted.

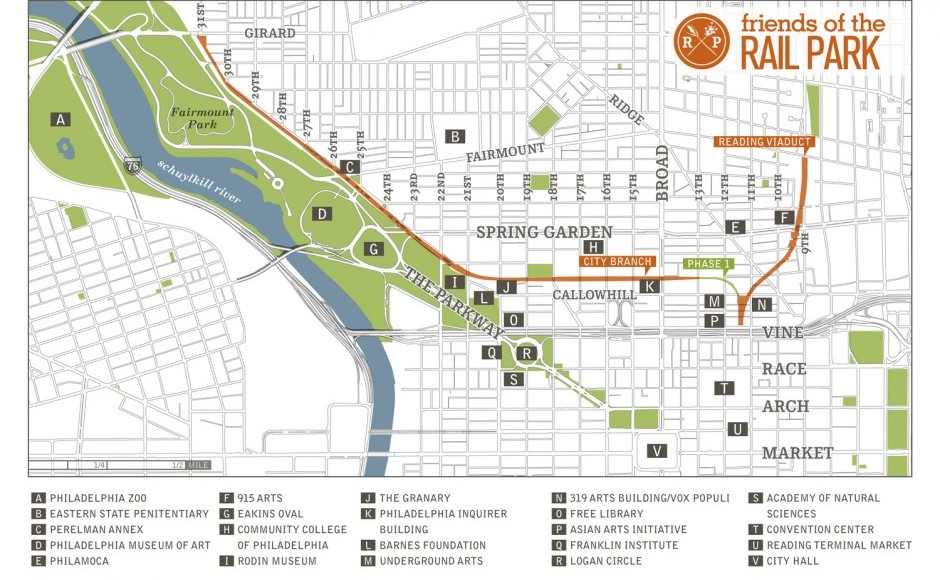

Source: Friends of the Rail Park

Before weighing the transportation benefits of the rail park, I should discuss the long-term plan for it. As the map above denotes, the proposal is broadly divided into two parts. In Phase 1, the elevated rail line would be repurposed, much like the High Line. In Phase 2, a 1.75-mile stretch of underground tunnels and dug-out space known as the City Branch (or, colloquially in transit circles, as “The Cut”) would be redone into a green corridor with paved throughways that might rival the cool factor of the Schuylkill Banks. (It would also link up with that trail by the Art Museum.) Collectively, both parts of the rail park would cover 55 city blocks and slice through 10 neighborhoods.

You’ve probably walked by the area in question without even knowing it. The Cut snakes underneath the Whole Foods in Callowhill, and runs adjacent to the Community College of Philadelphia and below Pennsylvania Avenue — all the way up to Fairmount Park. It was originally supposed to be part of a canal connecting the two rivers, though that project was never finished. Later bought by Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, The Cut served the industrial needs of companies like Baldwin Locomotive Works. (Its last customer was the Inquirer, in 1992.)

All of that’s to say that the Viaduct and The Cut are relics of our former transportation needs as an industrial metropolis — and, if Garden’s dreams are realized, their conversion into multi-modal corridors would be symbolic of Philadelphia’s recent transformation into a more walkable, bikeable city.

Planners have long wondered about a second life for The Cut as a transportation throughway. “The City Branch is unusual among 21st-century transportation infrastructure as a fully grade-separated facility in the heart of a major city without an immediately apparent transportation use,” reads an October study by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission. However, the study concluded that the high capital costs of creating bus-only lanes operating from Fairmount Avenue to Callowhill Street in the tunnel would not be justified.

“That study was good news for us,” says Garden, who takes me (and another interested observer) past the old Inquirer building on Broad, across the street and past the whirring fans of 401 North Broad, and then through a mucky patch of soil that leads to a chain-link fence. This is where Phase I of the Viaduct construction will begin later this year, if the anticipated funding comes through. More than half of the $9.6 million for Phase I has already been raised by the Center City District. That group is also waiting to hear back on three other state grant applications (worth $3.5 million, $1 million and $250,000, respectively). If the largest of the three grants is awarded soon, Friends of the Rail Park and Center City District could break ground by summer, and Phase I would theoretically be open to the public in 2017.

Garden envisions both the above-ground and below-ground portions of project as having ample room for bike lanes, running/pedestrian lanes, recreational space and even retail kiosks with coffee (and maybe some of those bougie popsicles).

The rail park will differ from the High Line in crucial ways. “We don’t think we’ll ever have that density, but we also have more space,” says Garden. The Viaduct is four tracks wide in most areas, twice the width of the High Line; The Cut is 50 feet wide. Once completed, commuters could bypass the Museum District and Parkway entirely, walking from 25th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue to east of Broad along a green pathway dotted with Paulownia trees.

“It would not only encourage more people to walk to work from these neighborhoods, but it would also take pedestrians off the street and make street flow a little better,” says Garden. “It would also inspire a lot more people to ride bicycles to and from Center City, because of both the pleasure factor and safety factor.”

The upshot, Garden says, is that the rail park project would create a more efficient way for bikers and pedestrians to travel from Brewerytown or Northern Liberties to just outside Center City. I’d argue that the proposed rail park would not be transformative in the way that, say, stripping parking minimums from the zoning code or creating rapid transit on Roosevelt Boulevard would be. In that sense, maybe it’s a luxury transportation improvement. Nonetheless, it’s one that the city deserves.

Follow @malcolmburnley on Twitter.