The Cul-de-Sac Is Dying

Dead ends in Montgomery County. | Google maps.

The cul-de-sac, the defining design feature of suburban America, is falling out of favor.

A new study by two researchers from McGill University and the University of California-Santa Cruz measures sprawl in a new interesting way, quantifying it by measuring road connectivity — that is, how many cul-de-sacs are in a place, compared to how many multi-pronged intersections.

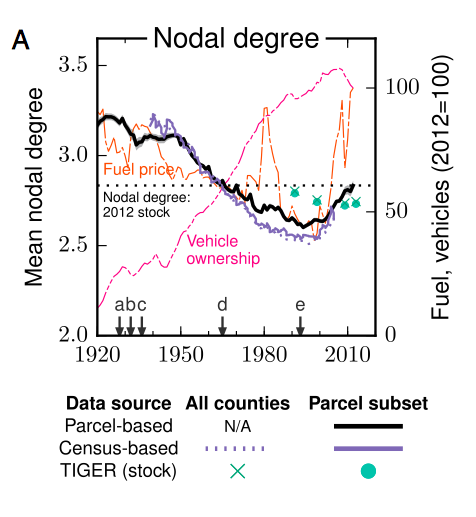

The study looked at nearly a century’s worth (1920 to 2012) of data on street designs to generate a long-term measurement of the connectivity of the country’s roadways, measuring sprawl using three main inputs:

- The average nodal degree of intersections (in English: how many incoming roads there are at each intersection)

- The number of dead-end roads

- The prevalence of intersections with four or more roads.

Similar to past research suggesting that “peak sprawl” occurred in the mid-’90s, this study concludes that road connectivity was at its worse about 20 years ago. Specifically, sprawl crested in 1994 (when intersections had an average nodal degree of 2.6) and then dropped by 9 percent between ’94 and 2012.

There are a few key lessons to take away from this overwhelming chart.

One — noted by that black trend line — is that intersections grew less interconnected over the course of the 20th century. That means instead of more five-point, plus-sign (+) and T-shaped intersections, there were more and more cul-de-sacs and dead-end streets. Further, this trend developed in spite of rising fuel prices (that’s the orange line). Finally, the move toward less-connected roads predated the astronomical explosion of car ownership amongst Americans (that’s the pink line) and white-flight to the suburbs. Thus, it seems that the growth of urban sprawl was a consequence of deliberate, decentralized planning, more than it was a response to the post-war tastes of the country.

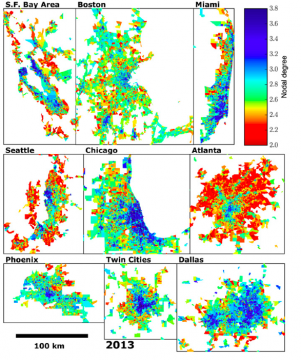

When the researchers zeroed in on individual metro areas, the average nodal degree of intersections was higher than the country overall, but the historical movement toward fewer intersections mirrored that of the nation. That’s changed in the last 20 years, with new, denser development in many big city suburbs:

Development in the suburbs of Seattle, the San Francisco Bay Area, and Dallas have shown significant increases in nodal degree, whereas the metropolitan area of Atlanta appears to have continued its embrace of low-connectivity, cul-de-sac road networks. In Boston, development patterns appear to have been different in the northern suburbs (higher nodal degree) than in the western areas.

In this graphic, the bluer the area, the more nodes at the intersections.

Unfortunately, the study authors didn’t zoom in on Philadelphia.

Sprawl is a problematic feature for any metro area, including Philadelphia, because it brings with it an increase of nasty externalities like greenhouse gases, obesity and racial segregation. By one recent analysis, Philly ranked 33rd out of 150 big cities in the country (well below Los Angeles, in fact) when it comes to sprawl, so the struggle is real.

But the study offers an optimistic take on how sprawl can be mitigated, to a degree, through careful policy considerations: “the largest increases in connectivity have occurred in places with policies to promote gridded streets and similar New Urbanist design principles,” the authors write.

It’s time to kill more cul-de-sacs.